This essay is part of the Islam on the Edges research portfolio hosted on the Maydan as a collaboration of the Center for Islam in the Contemporary World at Shenandoah University (CICW) and the AbuSulayman Center for Global Islamic Studies at George Mason University (CGIS). Learn more at themaydan.com/2022/01/edges/ and submit pitches to publish@themaydan.com.

This essay is part of the Islam on the Edges research portfolio hosted on the Maydan as a collaboration of the Center for Islam in the Contemporary World at Shenandoah University (CICW) and the AbuSulayman Center for Global Islamic Studies at George Mason University (CGIS). Learn more at themaydan.com/2022/01/edges/ and submit pitches to publish@themaydan.com.

Review Essay by Dženita Karić, Harun Buljina, and Piro Rexhepi. Muslims and the Making of Modern Europe by Emily Greble. New York: Oxford University Press, 2021. 376 pages. $35.00

Agency: everybody has it. But the agency of the marginalized is an especially sought-after commodity in contemporary Western scholarship. Much academic writing attaches an “emancipatory” valence to agency, using it “as a synonym for resistance to relations of domination,” as Saba Mahmood cautioned in her critique of this notion.[1] And despite many other critiques, this feel-good implication of agency persists. Just invoking the agency of the marginalized can confer an aura of virtue as well as innovation on the academic who wields this slippery but potent contraption.

Consider a recent book by historian Emily Greble, which claims to restore agency to Muslims in “the Making of Modern Europe.” The book takes a small slice of Muslim history on the European continent—namely pertaining to the Muslims of what became Yugoslavia in the period 1878-1948—to make a series of upbeat assertions about reintegrating “Muslims into the telling of European history.” Muslims were “not newcomers but indigenous inhabitants” of southeastern Europe, Greble first assures an implicitly skeptical reader. And there is more: since the nineteenth century, Muslims have “found spaces for agency in European states” and ended up “shaping the European project itself.”

But in the book, this promise of Muslim agency principally manifests itself as the withdrawal of Muslims into a hermetic safe space simply labeled “the Shari’a,” a term that Greble constantly invokes but never defines. In fact, as the chapters unfold, a very different story becomes visible underneath the feel-good surface of its sweeping claims. As historians have long shown, multiple European states have used “the Shari’a judiciary as a mechanism to intervene in and supervise Muslims’ lives.” Indeed, it is European legal structures that are at the heart of this book as well. Across the Yugoslav space, various state authorities ultimately end up not only abolishing or co-opting Sharia structures, but also deporting, expelling, and murdering the region’s Muslims themselves over the course of the twentieth century. It is hard to see how this story of Muslim retreat, whether into the Sharia or Anatolia, entailed them actively shaping “modern Europe,” as Greble does not give any convincing examples that it did. Her book will certainly, however, change how other scholars perceive Muslims in southeastern Europe, portraying them as an exotic community whose only consistent trait is this alleged obsession with Islamic law.

The glaring problems of Greble’s book—from this incoherent argument to its numerous interpretive and factual errors—have not prevented it from becoming one of the most decorated titles in European history since its publication in the fall of 2021.[2] Many reviewers seem starstruck by its generic claim that Muslims had agency. They have therefore especially praised Greble’s “approach to the topic from a Muslim perspective,” “foregrounding of Muslim voices,” and “triumphant restoration of Muslim agency.”[3] The more subdued among them have also described it as “an extraordinary, compellingly argued, and dazzlingly rich book,” or otherwise simply credited it with “bringing together European and Sharia law, cultural, social and political history [spanning] centuries.”[4] And yet, despite this unprecedented acclaim, the book has still not been subject to virtually any critique from experts in Balkan Muslim history, including from those within the communities under study. Muslims across Yugoslavia apparently exercised their agency in powerful ways in the past, but in the present they have little to no input into the state of modern European historiography. If this discrepancy appears surprising, it also evinces a certain logic: this is a history of Balkan Muslims that has not so much received its plaudits and appraisals as such, but rather as a comforting story that promises inclusive Europeanness and ostensible Muslim empowerment while asking little of its primarily Western readership. It is, in short, a book about Balkan Muslims, but not for Balkan Muslims in any meaningful way.

The glaring problems of Greble’s book—from this incoherent argument to its numerous interpretive and factual errors—have not prevented it from becoming one of the most decorated titles in European history since its publication in the fall of 2021.[2]

This exclusion of critical Balkan and, in particular, Balkan Muslim perspectives has lent the book a specious sense of academic consensus and obscured significant scholarly flaws. Among a number of interrelated issues, “Muslims and the Making of Modern Europe” deserves robust criticism for its analytical vagueness, erasure of key aspects of Balkan Muslim history, erroneous and tendentious reading of sources, overall Eurocentric bent, and heavy-handed legal reductionism in its understanding of Islam. Together with its sanguine emphasis on “agency” and “empowerment” in the face of the European violence inflicted upon Balkan Muslim communities in both past and present, Greble’s work ultimately poses more troubling questions regarding the relationship between Muslims, Europe, and academic knowledge production than its author likely intended.

Fuzzy Categories, Categorical Claims

In the simplest terms, “Muslims and the Making of Modern Europe” has two major problems: with Muslims and with Europe. More specifically, it has a problem with defining and delineating both, which results in both the extreme vagueness of these terms as well as the proliferation of adjacent concepts with imprecise denotations (e.g. “agency,” “voices,” “empowerment,” etc.). The issue is twofold: Europe is not only left undefined (Is it a geographic region? A cultural complex with a shared religious tradition and history? A synonym for a particular system of interstate law and politics?), it is never even brought into question. At times, this analytical vagueness approaches outright contradiction; where the introduction pointedly asserts that Muslims “have been part of European history from the beginning” and “were not newcomers but indigenous inhabitants” (pp. 8-9), chapter one hinges the book’s entire historical narrative on the idea that “Europe acquired over a million Muslim citizens in 1878” (p. 29). In this manner, Greble subtly contorts her core categories of analysis—Europe, Muslims, Citizenship, Sharia, and more—to suit whatever the purpose at hand. The author is aware, of course, of the many meanings of Europe in history, but her argumentative claims often hide behind this categorical ambiguity.

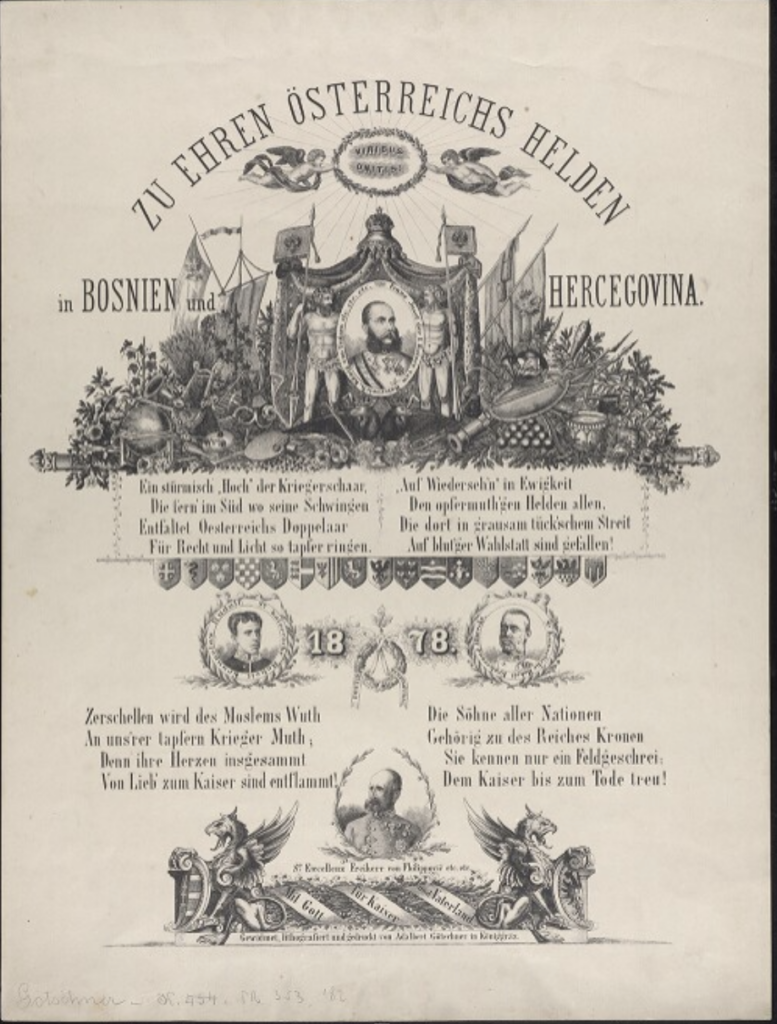

As with “Europe,” so too with “Europeans.” Muslims are frequently referred to as Europeans, or belonging to Europe, but even aside from the analytical imprecision, these statements come off as banal and trite: sentences ostentatiously likening Muslims to “other Europeans” recur throughout.[5] Elsewhere, however, we learn that “Europeans never accepted Islam as part of the European project, even when they granted Muslims citizenship” (p. 19), and that, “In the minds of Europeans, Muslims were necessarily tied to their faith in ways that other communities were not” (p. 130). The reader is left to draw one of two plausible conclusions: either some of the author’s Europeans were, in fact, a little more European than others, or the very category of Europeanness is fundamentally amorphous, with both interpretations rendering claims of Muslim “belonging” meaningless. A more subtle consequence of these would-be taxonomies is that the book also quietly elevates the Balkans’ Christian states and inhabitants to the status of unquestioned Europeans. Where more sophisticated histories of the region have long probed the ways in which these subjects negotiated “European” status as relative outsiders themselves, Greble’s analysis depends on a binary between Muslims and “European states” in which Austria-Hungary, Serbia, Montenegro, and later both royal and socialist Yugoslavia are all, essentially, the same: carriers of a “Christian-inflected modernity” faced with Muslim “citizens” (p. 11).

Where more sophisticated histories of the region have long probed the ways in which these subjects negotiated “European” status as relative outsiders themselves, Greble’s analysis depends on a binary between Muslims and “European states” in which Austria-Hungary, Serbia, Montenegro, and later both royal and socialist Yugoslavia are all, essentially, the same…

Greble’s conception of Balkan Muslim experiences as “European” history is closely intertwined with her choice of temporal and geographic scope. The book embarks on its narrative with the 1878 Congress of Berlin, which Greble sees as turning a large portion of Balkan Muslims into European citizens. Despite unconvincing claims to the contrary (p. 11), this periodization fundamentally cuts Ottoman developments out of the picture. This applies both to those that unfolded over the preceding century as well as those taking place in parallel in parts of the Balkans that remained longer under Ottoman rule. For instance, the book makes a great deal out of the intersection of civic and Islamic law, but it largely ignores the Mecelle, the pioneering Ottoman legal code that synthesized the two traditions in the 1870s and endured in many places into the twentieth century.[6] Similarly, it repeatedly cites state anxieties over Muslim military service—and particularly conscription exemptions for theological students—as a characteristic tension of non-Muslim rule under a novel (“European”) citizenship regime (p. 45, p. 101). In fact, conflicts between provincial Muslims and the Ottoman center over the terms of military service were a recurring feature of the Ottoman state’s fiscal-military consolidation since Sultan Selim III’s “New Order” in the late eighteenth century, while consternations over the privileges of madrasa students in particular profoundly shaped the post-1878 Hamidian state as well.[7] This insistence on 1878 as year zero also stands apart for its historiographical echoes: where recent Ottomanist scholarship has broadly sought to integrate the Balkans into global histories of plural modernities, Greble’s book recalls more than a century of Eurocentric scholarship on the region that equated the end of Ottoman rule with the onset of Western political modernity.[8]

Greble’s stress on the rupture of 1878 depends on a questionable reading of European history as well. Despite the centrality of that year’s Treaty of Berlin, the book is vague about what the Treaty actually entailed, only rarely citing specific provisions and otherwise preferring to provide abstract descriptions. These characterizations, however, routinely overstate the centrality of Balkan Muslims to the deliberations over religious rights, even going as far as suggesting that European statesmen intended the Treaty “as a corrective” to earlier episodes of anti-Muslim violence in the region (p. 41). In reality, the Treaty provided more of a blanket guarantee of civic rights and religious freedom in which Muslims were a secondary consideration. Far more important was the position of Balkan Jews, with Western Jewish organizations pushing diplomats to establish a key council on anti-Jewish prejudice, whose findings then directly led to the stipulations on minority rights for the newly independent Balkan states that Greble takes as her point of departure.[9] In the same vein, Greble downplays the anti-Muslim prejudice of European statesmen of the time, at one point citing William E. Gladstone’s 1876 pamphlet calling on “the Turks” to expel themselves from Europe—”one and all, bag and baggage”—as evidence for “a conceptual shift of disaggregating the idea of ‘Muslims’ from the idea of ‘Turks’” and allowing some of the former to stay on their lands (p. 29). Given the fact that “Turks” remained a generic label for Balkan Muslims well into the twentieth century, this reading seems implausible at best. If such a pivotal shift indeed occurred at this time, it requires much more compelling evidence than Greble provides.

In terms of space, Greble identifies her subjects as the Muslim residents of Serbia, Montenegro, and Austria-Hungary after 1878 and 1912-1913 (p. 2). In reality, the book frequently shifts spatial frames unannounced, not only jumping across different contexts within this region, but sometimes even switching the focus entirely. Bulgaria and Greece, for instance, serve not only as points of comparison for this self-defined area of focus, but often even sneak into endnotes as evidence for claims that would appear to pertain to that primary area instead (p. 167, n. 11). Elsewhere, Greble repeatedly makes generic claims about the experience of “Muslims” that only apply to particular parts of this politically divided territory. As but one of myriad examples, a key claim of chapter 3, on the prolonged violence of the 1910s, holds that World War 1 offered local Muslim communities “the possibility of shifting undetermined power dynamics and asserting their own autonomy” (p. 101). To substantiate, Greble cites Bosnian Muslims’ attempt to create a centralized education system under wartime in 1916 (p. 102), but the war had decimated far more ambitious proposals that Bosnian ulama had devised during an earlier period of peace-time optimism.[10] By insisting on some general “Muslim” experience vis-à-vis state power that encompasses the entire region, the book ends up propagating a highly misleading portrayal of, in this case, Bosnian Muslim history. In effect, while at times offering a serviceable overview of regional trends, the pre-1918 narrative also not infrequently resembles an impressionistic collage.

Given Greble’s frequent invocations of Muslim “voices” (e.g. pp. 164-165) and “the way that the Muslims of [her] sources conceptualized their worlds” (p. 13), an uncomfortable question imposes itself: how is it that, in the decades of scholarship since, seemingly no Muslim scholars from the region had struck upon this specific combination of temporal and geographic scope themselves?

Given Greble’s frequent invocations of Muslim “voices” (e.g. pp. 164-165) and “the way that the Muslims of [her] sources conceptualized their worlds” (p. 13), an uncomfortable question imposes itself: how is it that, in the decades of scholarship since, seemingly no Muslim scholars from the region had struck upon this specific combination of temporal and geographic scope themselves? One compelling explanation would be that most Muslims in this time and space simply did not understand their communities through the horizons that Greble’s narrative anachronistically imposes. Muslim intellectuals thus frequently authored works that considered Muslims and Islam in both narrower and wider contexts, but few if any fused together Bosnia-Herzegovina, Serbia, Montenegro, the Sandžak, Kosovo, and Macedonia into a single whole spanning the better part of a century. Far from amounting to some fresh perspective, this scope ultimately reveals Greble’s enduring concern with the Yugoslav state, which came to rule over these disparate territories halfway through the period under study; indeed, the narrative only gains substantial coherence once Yugoslavia comes into existence.[11] Greble’s admission that the book started as a study of “Muslims in Yugoslavia” before pivoting to “center” Muslims themselves following the intervention of a concerned Ottomanist (pp. 12-13) cannot escape this underlying tension: fundamentally a state-based project, it awkwardly tries to reconcile this legalistic structure with claims to focus on subjects who did not neatly conceive of themselves within these bounds.

So who are Greble’s Muslims? The author argues that European (i.e. Balkan) states’ treatment of “Muslims” as a separate legal category “reified them as a community” (p. 15), particularly in the formative years of post-1918 Yugoslavia, where anti-Muslim violence and discrimination drove “diverse language and cultural communities [to coalesce] around this category” and “many Muslim leaders [to increasingly feel] a connection as Muslims” (pp. 112-114). From a general Europanist perspective, this sets Yugoslavia up as a convenient analogue to present-day Western European states, where post-war migrant communities with diverse ethno-national origins came to constitute a singular “Muslim” minority in the face of European prejudice—a comparison that Greble is eager to make herself (p. 7, p. 260). From the perspective of local historians, however, this framing sets off multiple alarms. Above all, it glosses over a much longer history of Muslim political activity along confessional lines (and, indeed, around the “Muslim” category) that simply does not fit within this Eurocentric and Yugoslav frame.[12] To be certain, the creation of Yugoslavia did create a new arena for some broader “Muslim” political and religious ventures, albeit with mixed results. It also belied an underlying ethno-linguistic and institutional-political division: between Slavic-speaking Muslims broadly tied to Bosnia-Herzegovina on the one hand (i.e. “Bosnian Muslims”, today also “Bosniaks”), and the largely Albanian-speaking Muslims in the “southern” territories Serbia conquered in 1912 on the other.[13] Though the book does not simply ignore this divide, its insistence on “Muslim” as some paramount legal-political category ends up erasing key aspects of the history of both.

The book’s limitations are easier to identify on the “Albanian” half of this equation. First, Albanian-speaking Muslims in the region variously faced persecution both as Albanians and as Muslims, including from both “European” and “Muslim” states. Their experiences therefore complicate any neat dichotomies between “European” states and “legally Muslim” citizens, with Albanian nationalism as a particularly confounding variable. To illustrate the tension between such European states and Muslim schooling, for instance, Greble highlights Montenegrin anxieties in 1914 over an independent Muslim school in Ulcinj as a site of “potential subversion” (p. 49). The archival documents she cites, however, suggest that the authorities were at least as worried about its Albanian-language instruction as its Islamic character per se, being perfectly willing to tolerate Islamic education in the Montenegrin language. The fact that an independent Albanian nation-state had come into existence a year earlier and barely 15 kilometers away would also seem to provide pertinent context, but Greble does not mention it. She also fails to mention that the establishment of this Albanian nation-state faced one of the most significant Muslim uprisings in the region, which defeated the troops of the International Control Commission and overthrew the European-appointed prince Wilhelm zu Wied. In fact, compared to the distinctly more tangential Bulgaria and Greece, the book hardly mentions Albania at all.[14] Later, in discussing World War 2, it duly notes that Kosovar demands of the Italian occupiers centered on an Albanian army and unification with Albania, but then reductively reads this as a demand for “increased Muslim sovereignty” (p. 223).

The second limitation, however, is even more fundamental: Greble does not work with sources in either Albanian or Turkish, leaving a massive methodological barrier between her and roughly half of the “Yugoslav Muslims” encompassed by her study. As a result, sections meant to cover developments in the Yugoslav “South” rely heavily on British diplomatic reports and Yugoslav government sources, with the latter in particular raising further questions about claims to recover previously unheard Muslim perspectives from state archives often indifferent or hostile to them. This lack of access leads Greble to frequently draw on materials from the largely Slavic-speaking Sandžak region between Bosnia and Kosovo instead, and while this focus may be welcome in theory given its longstanding historiographical neglect, problems arise when she relies on it as a stand-in for the (disproportionally Albanian-speaking) “South” as a whole. Most glaringly, the book’s repeated suggestions that connections and parallel developments between Bosnia and the Sandžak demonstrate some remarkable, legally-driven “Muslim” solidarity novel to the Yugoslav era are misleading (p. 176, p. 187). While it may be true that these two regions “had distinct historical paths” in the years 1878-1918 (p. 128), they also shared linguistic, migrational, and political ties that had persisted and stretched back centuries.[15]

As for Bosnia-Herzegovina, the author often appears palpably hesitant to employ “Bosnian Muslim” as an analytically useful modifier at all.[16]

As for Bosnia-Herzegovina, the author often appears palpably hesitant to employ “Bosnian Muslim” as an analytically useful modifier at all.[16] This omission of references to specifically Bosnian developments effectively wipes the slate clean so that Greble can assert her argument that “Muslim” functioned as a pan-Yugoslav legal category beyond regional and other intra-confessional differences. The book is therefore full of ambiguous references to, for example, Yugoslavia’s “Muslim elites,” but a closer reading reveals these elites to be almost exclusively Bosnian (as becomes readily apparent by consulting the cited primary and secondary sources). In fact, given her linguistic limitations vis-à-vis the southern regions of Yugoslavia, these unnamed Bosnians form the lion’s share of Greble’s subject matter and “Muslim” source base. The entire discussion of “Muslim reformists” in chapter 5 is exemplary (pp. 152-154). Referring to a 1919 meeting of Bosnian ulama discussing institutional restructuring and educational reform, Greble stresses that the reformists advocated for “Serbo-Croatian classes at every level” of Muslim schooling, but omits mentioning that the only reference to language in the cited source is paired tightly with a call to teach Muslim students “the basics of the geography of Bosnia-Herzegovina,” and in fact makes no reference to “Serbo-Croatian” at all.[17] She also avoids mentioning that the Islamic institutions she is discussing, and in particular the “Islamic Religious Community,” remained specifically tied to Bosnia-Herzegovina (as opposed to the entirety of the post-1918 Yugoslav state) until the royal dictatorship of 1929.[18] While reluctance to project contemporary national and political categories into the past may be generally commendable, Greble’s work therefore errs toward the opposite extreme, crafting a narrative in which Bosnian Muslims are often conspicuously—and, in fact, artificially—absent as such.[19]

At its most extreme, Greble’s book essentially implies that it was only the contested implementation and eventual reversal of her Sharia Mandate that led to the development of a “culturally” Muslim and ostensibly secular Bosniak national politics in the second half of the twentieth century (p. 249).

This blind spot is even more apparent in the book’s treatment of Bosnian autonomy, which has long formed a central concern of Bosnian Muslim political thought. In interwar Yugoslavia, preserving at least the outline of Bosnian administrative borders represented one of the Yugoslav Muslim Organization (JMO) political party’s critical interests, and a crowning achievement of its negotiations with Serb counterparts over the new Yugoslav constitution. But Greble’s long discussions of (Bosnian) Muslim engagement with the early Yugoslav framework are strangely quiet on this issue of autonomy (p. 109), while insisting instead that “[Muslims placed] rights to Shari’a at the forefront of their demands” (p. 131).[20] Correspondingly, where Yugoslav historians framed the JMO’s influence on the constitution primarily in terms of the preservation of Bosnian borders through the pejoratively-labeled “Turkish paragraph” (Article 135), Greble makes no mention of this clause, promoting instead her own coinage of a “Shari’a Mandate” (p. 129) (Article 109). As a result, when the narrative reaches the 1939 Cvetković-Maček agreement, which partitioned Bosnia-Herzegovina’s historical territory into “Serb” and “Croat” halves by ignoring Muslims as a demographic factor entirely, Greble can only depict it as an abrupt development that shocked Bosnian Muslims into newly considering the question of territorial autonomy (p. 188). At its most extreme, Greble’s book essentially implies that it was only the contested implementation and eventual reversal of her Sharia Mandate that led to the development of a “culturally” Muslim and ostensibly secular Bosniak national politics in the second half of the twentieth century (p. 249). Taken together, this all amounts to one of the book’s central ironies: lauded as a restoration of Muslim agency, it in fact flattens and obscures critical aspects of local Muslim histories in the service of a narrative focused on the twentieth century Yugoslav state and appealing to a Western audience.

Phantom Citizenship

Central to Greble’s consideration of “Europe” and “Muslims” is the category of “Citizenship,” which serves both for delineating the book’s subject matter as within European history and interpreting its Muslim subjects’ engagement with European states. According to the book’s introduction, in stark contrast to Muslims elsewhere in the world, those “at the center of this book were not a product of the systems of European colonialism” (p. 7). In particular, while European empires provided the former with “Islamic rights instead of citizenship rights, the countries explored in this study… provided Muslims with distinct Islamic rights because they were citizens” (p. 14). Unfortunately, the author never explicitly defines citizenship, leaving it as yet another fuzzy category à la “Europe.” In less prominent corners of the book, particularly those covering the pre-Yugoslav period, Greble effectively concedes as much. “Subjecthood and citizenship,” we learn, “coexisted… on a continuum,” while “political rights and constitutional governance” similarly “remained abstract ideas with flexible meanings… varying degrees… [and] often incoherent structures” (p. 30). In some cases, such as early twentieth century Montenegro, she admits that the Muslims under study might not even be said to have had “inherent rights as members of the citizenry” at all (p. 43). So why interpret large swathes of local Muslim history through a category of analysis that hardly applied? Greble waves such concerns away by emphasizing how “the international legal framework… [was moving] toward citizenship,” whatever this ideal type may have entailed (p. 31). The stress seems to be on the inclusive but unrealized promise of the letter of the law, whose overall trajectory ultimately redeems any earlier shortcomings. But does this comforting thought warrant sharply demarcating our understanding of Balkan Muslims’ historical experiences as categorically different—and, indeed, “European”—relative to that of Muslims in Europe’s colonial empires?

…the inclusion of Austro-Hungarian Bosnia-Herzegovina forms one of the fundamental tensions in the entire first half of the book. Greble’s analytical concerns are most at home in post-1878 Serbia, a nation-state whose decimated Muslim minority theoretically held civic rights in a constitutional regime.

In this regard, the inclusion of Austro-Hungarian Bosnia-Herzegovina forms one of the fundamental tensions in the entire first half of the book. Greble’s analytical concerns are most at home in post-1878 Serbia, a nation-state whose decimated Muslim minority theoretically held civic rights in a constitutional regime. With the same applying to Montenegro after 1905, this makes for two pre-1918 political contexts where the emphasis on “citizenship” makes some sense. Greble, however, does not consider Serbia and Montenegro comparatively with Bosnia-Herzegovina under a common rubric of “Muslim citizenship,” but instead treats the three territories as essentially equivalent cases of a single coherent phenomenon. This framing is jarring precisely because the lack of formal citizenship and constitutional rights was one of the defining features of the Austro-Hungarian occupation. Unlike any other territories in the Dual Monarchy, Bosnia-Herzegovina was ruled directly by the Imperial Minister of Finance. Bosnians under occupation were also explicitly excluded from both Austrian and Hungarian citizenship and could not elect representatives to either Vienna or Budapest or their annual delegations.[21] Even the provincial parliament was not established until 1910, with its resolutions still requiring approval by the occupying authorities.[22] Bosnian Muslims therefore only acquired “citizenship” in the most abstract sense of the term, but even then in a way fundamentally distinct from citizens in Serbia, Montenegro, and even the remainder of the Habsburg domains. To obscure this discrepancy, Greble relies on a tendentious portrayal of the historical record, where everything from reluctance to enroll children in state primary schools (p. 50) to a one-off 1906 lecture on the Austro-Hungarian legal system at Sarajevo’s Sharia Judges’ School (p. 61) somehow demonstrates Bosnian Muslims’ engagement with their phantom citizenship.

Rather than a colonial takeover by a foreign power, Greble paints Austria-Hungary’s occupation of Bosnia-Herzegovina as an almost auspicious moment that allowed Muslims to acquire citizenship through demands for rights and representation. This entails both selective praise of the more ostensibly inclusive aspects of Austro-Hungarian rule and a blind eye toward its more overtly imperialist elements. In fact, Viennese statesmen would have likely been surprised by Greble’s assertion that their rule over Muslim subjects amounted to something fundamentally different from other European colonial holdings, as they openly drew on examples from British-occupied Egypt, French Algeria, and the Dutch East Indies in overseeing the development of Bosnian Islamic institutions.[23] Austro-Hungarian officials even explicitly sought inspiration from French Algeria and its colonial Shari’a code in imposing their own 1883 transformation of Shari’a courts, but Greble is silent on this history.[24] Instead, she singles out the appointment of Mustafa-beg Fadilpašić as Sarajevo’s “first mayor,” which she believes “symbolized the new regime’s commitment to working with the local Muslim elite to establish peace,” further citing the existence of Muslim political parties in the 1910 parliament (p. 30). Putting aside the fact that Fadilpašić had an immediate Ottoman-era predecessor in Ragib ef. Ćurčić, this is a highly sanitized depiction of Muslim political participation during the occupation, whitewashing both the mayor’s very limited power and the decades of struggle with the occupying authorities that produced said parties and parliament. Greble thus claims that Bosnian Muslims were not shaped by “the systems of European colonialism,” despite ample evidence that Austro-Hungarian officials positioned Bosnia-Herzegovina alongside other European colonial models.[25] This colonial dimension was also something that Bosnian Muslims were aware of themselves, drawing comparisons between their political status—specifically lack of democratic rights—and similar cases in Africa and Siberia.[26]

This approach extends to the next major episode of colonial violence under Greble’s purview: Balkan states’ violent conquest of Muslim-majority Ottoman territories during the 1912-13 Balkan Wars, as well as subsequent decades of oppression of the predominantly Albanian-speaking population inhabiting these lands. Drawing on European consular reports, Greble does account for some of this anti-Muslim violence, but never situates it in a global context marked by the previous year’s Italian invasion of Ottoman Libya or related developments in other European colonies.[27] The struggle for Muslim rights that followed in these formerly Ottoman territories was not, however, separate from the larger transnational anti-colonial struggles of the era. Indeed, Muslims in India could even regard the position of their coreligionists in the Balkans as worse that their own, with an editorial in the Times of India noting their apprehension “that they will be persecuted by the Christian government of Albania as they are in Montenegro and Serbia, where hundreds of families are being forced into exile because they are Albanian Mohammedans.”[28] It is also surprising that someone like Greble, who has carried out work in the Yugoslav archives on Muslim populations, would not have herself come across the extensive colonization practices that were implemented.[29] Greble insists that Serbia was European but not pursuing European colonial policies in regard to its Muslims, glossing over its most expansive policy in dealing with them: the colonization of its post-1912 Southern Provinces.

These omissions and obscurations indicate a variety of theoretical problems in Greble’s study which collectively amount to what we might call a “Eurocentric Isolationism” in her approach to Balkan Muslim history. When Greble argues that “[t]he Muslims at the center of this book were not a product of the systems of European colonialism,” she not only suggests that Muslims in the Balkans were not subject to colonial violence, but that their Europeanness seems to have made them immune to colonialism. The question ultimately becomes: where are we looking at Muslims in the Balkans from? Because a view from the global south produces a different picture from the one that Greble presents. Her book’s insistence on the Balkan Muslim experience as fundamentally “European” therefore not only goes against many of the most provocative works in its own subfield, but also much of the literature in Middle Eastern and Islamic Studies at large, which has sought to emphasize these connections in light of the arbitrary yet persistent divides of area studies. It also obscures how Muslims in the Balkans today, unlike their non-Muslim neighbors, face similar Western-imposed fragmented sovereignties as non-European contexts such as Afghanistan and Iraq, where Joe Biden in fact touted Bosnia’s “Dayton” constitution as a viable model.[30]

Again, it is difficult to understand what makes Muslims in the Balkans so different from Muslims under colonial rule across the world. One assumption would be that Muslims in the Balkans after 1878 were granted certain “rights” related to Islamic law. Yet Muslims across British and French colonies enjoyed rights to Islamic law in a similar legally pluralistic way that Muslims in the Habsburg Empire, Serbia, Bulgaria, and Greece did. If “citizenship” differed somehow—and it is not clear from the book how—Greble still fails to engage with an expansive and complex literature on how claims to rights and responsibilities by colonized subjects transformed the very concept of citizenship.[31] Greble also never seriously engages with the comparative perspective that her claims of Balkan Muslims’ “European” status and global distinctiveness would require. It is a surprising oversight, for instance, to fail to account for the differences between occupied Bosnians and full citizens of Austria and Hungary, a difference that would have challenged Greble’s notions of citizenship—if we assume that legal equality, representation, and inclusion within the body politic distinguishes citizenship from colonial rule. But then even if we assume that some form of citizenship was granted, Greble goes on to say “Muslim citizenship became employed as a tool for the erasure and subjugation of Muslims within new European states” (p. 27). So to what end is this treatment of Muslims in the Balkans categorically different from, say, Muslims in Morocco under French rule or Muslims in India under British rule? As the book makes very few references to what these concrete differences may have been, it is difficult to take such sweeping statements seriously.[32]

Even in those Balkan contexts where colonialism may be less salient as an analytical frame, Greble’s insistence on citizenship leads to a distorted picture of the historical record.

Even in those Balkan contexts where colonialism may be less salient as an analytical frame, Greble’s insistence on citizenship leads to a distorted picture of the historical record. Consider, for instance, the following descriptions of (Bosnian) Muslim intellectuals’ priorities during the 1920s: “[Reis-ul-ulama] Čaušević and other reformists hoped to recast Yugoslavia’s diverse Muslims into modern Muslim citizens equipped with the necessary tools for active civic engagement” (p. 153); “Education would serve as the principal vehicle for forging this new generation of Muslim citizens” (p. 154); “[The reformists] recognized the urgency of defining themselves squarely within the citizenry” (p. 154).[33] Readers unfamiliar with the source base in question might rightly assume that this repeated stress on “citizenship” reflects these Muslim reformists’ own “voices.” To the contrary, it is all Greble: in the documents she cites, Čaušević makes little to no mention of “citizenship,” much less as a central goal or motivating principle.[34] Although the formation of the new Yugoslav state and relations with Belgrade obviously represented the immediate political context, Čaušević and his allies primarily framed their activism in terms of a modernist imperative of “progress” and Social Darwinian anxieties over communal viability—influences completely absent in Greble’s analysis. Moreover, nearly all of the debates Greble explicitly identifies as novel to the era of Yugoslav constitutionalism—doctrinal disputes, educational reform, the status of women, etc.—appeared earlier under Austria-Hungary as well (p. 152).

The book therefore places an unwarranted insistence on the centrality of Yugoslav citizenship in driving (Bosnian) Muslim intellectual life, which introduces certain tensions in regard to the larger claim of Muslim “agency” as well. The author thus stresses that “prominent Islamic scholars” in the 1920s responded to the new “nationalizing state” by utilizing their “Shari’a mandate” to mold “a unitary Yugoslav Muslim minority” (p. 152). In her later discussion of the royal dictatorship, however, Greble alleges that the government takeover of the institutions of this “Shari’a mandate” amounted to an attempt to turn “the diverse communities of Muslims living in the region” into a single community of “Yugoslav Muslims” (p. 184). Putting aside a more thorough consideration of whether these claims are historically accurate, readers are left to wonder if attempts to create a uniform Yugoslav Muslim community through “Shari’a” institutions represented an example of Muslim “agency” or “marginalization.” And if the distinction depends merely on the agents in question, then what is the significance of such Muslim “agency” in the first place? But the issue is broader still: the book’s chapters provide numerous such examples of state officials manipulating vulnerable and increasingly marginalized Muslim communities, while the introduction and conclusion insist on an overarching story of uplifting “Muslim agency.” The jarring contrast between “agency” and “marginalization” is thus swept under the rug to celebrate undefined (“European”) notions of citizenship and inclusion.

Greble’s analysis of Muslim “citizenship” and “agency” routinely involves these types of distortions and inconsistencies. Another major example occurs in chapter 4, which covers the founding of Yugoslavia. In the chapter’s opening lines, Greble cites a 1918 issue of the Mostar journal Biser, whose editors—she claims—promised to “not discuss daily political issues, since our viewpoint is that spiritual enlightenment and improvement is more important for our people than some empty politics” (p. 107). Greble leans heavily on this statement, referring to it in the rest of the chapter and using it to argue that “Muslims”—note again the generic label for a specifically Bosnian Muslim context—responded to the chaos of postwar politics by steering clear of the emerging claims to national self-determination in favor of a familiar confessional domain (p. 109). This is both a provocative and highly consequential assertion in Greble’s larger argument, but it faces a fundamental problem: the editorial statement she ascribes to January of 1918 actually came out in Biser’s very first issue in June of 1912, in the completely different context preceding the Great War.[35] In short, Greble mistakes pre-war discourses for post-war developments. Such basic empirical lapses do not inspire confidence in the book’s sweeping arguments.[36]

Even if we ignore the fact that Biser’s editors actually advocated for a global Pan-Islamist outlook, Greble’s claim that Muslims in Yugoslavia “disassociate[d] themselves from” wider talk of borders, empires, and nation-states remains dubious.[37] After all, what was the “Committee for the National Defense on [sic] Kosovo” concerned about if not “how the war might end [and] what states would rise or fall” (pp. 112-113)? And what was Bosnian Muslim leaders’ insistence on maintaining Bosnia-Herzegovina’s administrative borders within the emerging Yugoslav state—which, again, the book minimizes—if not a concern with “what postwar boundaries might look like”?[38] In short, Greble’s implied dichotomy between Muslim communal politics at the dawn of Yugoslavia and the larger political questions of the age seems overstated and based on a lack of engagement with the pre-1914 circumstances, an erroneous reading of key sources, and a consistent desire to present the Yugoslav constitutional framework (“citizenship”) and “nation-building” as molding Muslim political agency. “Muslims and the Making of Modern Europe” thus alternates between downplaying colonial aspects of Balkan Muslim history and, in their place, overstating the importance of an abstract “citizenship.” Both tendencies then relate to another overarching issue with the book: its reductive legalist understanding of Muslim lives, institutions, and politics.

Legalistic Reductionism and “the Shari’a”

Arguably the central flaw of “Muslims and the Making of Modern Europe” lies in its insistence on reducing the amplitude of Balkan Muslim lives and historical experiences to one single facet—that of their legal status and the debates surrounding it. As Greble puts it in the book’s opening pages, the Muslims under study understood themselves as “legally Muslim,” inhabitants of “a particular legal world that existed in mid-twentieth-century Europe”; “for them, being Muslim was not simply a confessional identity or a matter of belief but a legal category, enshrined in decades of legal codes, institutionalized in the structures of state institutions, and embedded in the region’s frameworks for belonging” (p. 2). As an implicit comment on the existing literature and readers’ expectations, however, Greble’s characterization here has it exactly backwards: it is precisely matters of religious belief and confessional solidarity that had been traditionally marginalized in the study of Balkan Islam, and that today feature in some of its most innovative work, as recent books and projects by David Henig and Larisa Jašarević illustrate.[39] By contrast, the field has for decades centered on the relationship between Muslim communities and various state projects (and, for that matter, “Europe”), of which Greble’s monograph represents the latest iteration.

Perhaps the most persistent and problematic of these is Greble’s insistence on the category of “Shari’a.” Crucially, this insistence is not simply a reflection of her source base or the social milieu under study. To the contrary, Greble adopts an all-encompassing and rigidly legalist conception of Sharia…

Greble’s legalistic understanding of Islam ultimately harkens back even further, to classical Orientalism as defined by Edward Said, obsessed as it was with Islam’s alleged scripturalism and unchanging legal codes. Thinking about Muslims and Islam exclusively in terms of law is therefore nothing new, and has been a preoccupation of Orientalists and Muslim reformists alike for well over a century. Critiques of such a narrow focus are nothing new either. Several years ago, in his highly acclaimed book “What is Islam? The Importance of Being Islamic,” Shahab Ahmed decried how “this totalizing ‘legal-supremacist’ conceptualization of Islam as law, whereby the ‘essence’ of Islam is a phenomenon of prescription and proscription, induces, indeed constrains us to think of Muslims as subjects who are defined and constituted by and in a cult of regulation, restriction and control.”[40] Rather than consulting these debates and discussions surrounding legalism in Islamic and religious studies, Greble essentially ignores such intellectual legacies and presents her work as some departure from the mold, an original contribution. In fact, it is yet another aspect of the methodological conservatism at the book’s core, leading the author to numerous and avoidable blind spots.

Perhaps the most persistent and problematic of these is Greble’s insistence on the category of “Shari’a.” Crucially, this insistence is not simply a reflection of her source base or the social milieu under study. To the contrary, Greble adopts an all-encompassing and rigidly legalist conception of Sharia that would be foreign to most of the Muslim theologians in her book, and indeed regularly stretches her primary and secondary sources to make it stick. In one representative example, Greble cites a Bosnian-language article on Muslims detained in an Austro-Hungarian prison during World War 1, claiming that “the prison wardens initially demeaned Muslims and violated the Sharia” (p. 99, n. 87). The article itself, however, makes no mention of Sharia whatsoever, either from the article’s present-day author or in the letter by a contemporary theologian he cites, which instead simply refers to “Islamic prescripts.”[41] Rather than “foregrounding Muslim voices,” Greble effectively speaks over them. Even an article by Reis Čaušević himself referring to Islamic norms of cleanliness becomes, in Greble’s wording, a “critique [couched] in terms of religious law” (p. 153). “Law” thus conflates everything from divorce proceedings in a Sharia court to taking one’s shoes off before entering a house, eliminating the possibility that Islamic normativity could be conceived in anything but legal terms.

This self-assured legalism carries over to the book’s approach to Islamic institutions more generally, with Greble rarely missing an opportunity to reduce them to their legal aspects. Readers thus learn that the position of the Reis-ul-ulama, Bosnia-Herzegovina’s supreme Islamic religious authority, “was designed as a high-level Islamic judge” (p. 56), but happened to have some additional responsibilities in addition to this primary role as an “Islamic lawmaker” (p. 111). Similarly, the book regularly reduces members of the ulama to “legal authorities” (p. 18), cites an article describing the rejection of Reis Čaušević by the Bosnian ulama council’s electoral curia—a representative body tasked with choosing the Reis-ul-ulama—as amounting to condemnation from “every major [Muslim] legal association in Yugoslavia” (p. 159), and describes the government’s transfer of the Reis-ul-ulama’s office from Sarajevo to Belgrade as targeting the “Sharia mandate” (p. 182). Such reductionism is foreign to the existing literature in both Bosnian and Western languages, which sees Sharia courts as just one among several Islamic institutions that contemporary Muslims were concerned with (notably also including religious endowments, schools, and even new forms of associational life and print media), and the ulama in particular as holding a far broader social function than simply administering “Islamic law.” In Greble’s reading, however, virtually all Muslim institutions are fundamentally legal, allowing her to misleadingly conclude that “Islamic legal scholars [and] professionals [became] the principal intermediaries between communities of Muslims and new states” (p. 259).

This legalistic exclusivism ultimately shrinks the very notion of the Sharia from the vastness of values and principles underpinning the governance and cultivation of a religious life to a dry and overwhelmingly modernist phenomenon of Muslim “agency.” This is, despite Greble’s claim to the contrary, a move already seen in colonial discourses on the Sharia, which, as Khaled Abou El Fadl puts it, “rather than treating Shari’ah as a practised discipline of deliberative and purposeful practical reasoning… reduced Shari’ah to a code of duties and obligations that had a largely corrupting influence upon the way that the Shari’ah was understood and practised for centuries.”[42] In Greble’s book, the Sharia appears as an obsessive pursuit of Bosnian ulama in two domains in particular: (1) marriage and (2) property and inheritance laws.[43] While Bosnian ulama thought, wrote and spoke about a wider set of conceptual, spiritual, devotional and material issues related to tradition, modernity and the future, these two pursuits were indeed relevant, but especially in the context of what scholars such as Brinkley Messick have identified as “colonial Sharia”,[44] which also involved the European establishment of legal institutions different from their pre-modern Muslim equivalents, engagement with the local ulama, production of legal texts, and more.[45] It is therefore even more surprising that Greble refuses to engage with the proper colonial context of the shaping of Sharia for the modern age, preferring to hold onto a vague conception of “citizenship” which provided Muslims “distinct Islamic rights” (p. 14). In essence, an honest grappling with the Sharia—understood here in the narrow sense of state regulation of private and public affairs—would imply seriously considering countries such as Serbia, Montenegro, Austria-Hungary and Yugoslavia as partly colonial formations.

We have to ask ourselves: apart from the focus on the issues of marriage and property law, what is the Sharia in Greble’s book? What are its sources? Does it have continuity with understandings of the Sharia in premodernity? Who are its practitioners and its opponents? Unfortunately, our exasperated reader will not be able to find many answers. While “Shari’a” and “Islamic law” appear 274 times in the book’s 262 pages, the Hanafi legal school of thought—followed by Bosnian and Albanian Muslims in both past and present—is mentioned only twice, indicating that Greble is not interested in the substance of what actually constitutes the Sharia (whether understood in a narrow sense as a set of rules governing believers’ lives or in a wider sense as the moral and devotional underpinnings of Muslim religious life) and especially what elements and mechanisms of the Sharia were adjusted, reinterpreted, or repurposed for the conditions of the modern age.[46] In fact, the closest the book comes to defining Sharia is with a cursory line in its glossary, which describes it as “divine law for Muslims, as imagined by God” (p. xiv). Sadly, the theological implications of this imagining fall outside the scope of this review.

In terms of the particular institution of the post-1878 Sharia judiciary, these courts undoubtedly played a central role in Muslim socio-political life, but this only makes Greble’s persistent manipulations of the existing literature all the more frustrating. Consider the book’s introduction of the previously referenced JMO political party (p. 126). Greble draws extensively here on historian Fikret Karčić’s well-known study of Sharia courts in the first Yugoslavia from 1986 (republished in 2005), but Karčić himself drew there on research from his predecessor Atif Purivatra’s landmark studies of Bosnian Muslim party politics from the 1960s and 70s.[47] One critical difference looms large between the two authors: where Purivatra’s work centered on the JMO and Bosnian Muslim politics more generally, Karčić’s book was a specialist study on the institution of the Sharia courts. When Karčić cites Purivatra, therefore, it is not to challenge him with a revisionist, Sharia-centered interpretation of the JMO, but rather to draw on his research to illustrate how Sharia was also a prominent part of the party program. Where Karčić demonstrates how Sharia was a critical component of the JMO agenda, however, Greble cites him to suggest that it was the agenda. As a result, what generations of Bosnian scholars since Purivatra have rightly seen as equally important pillars of the JMO’s politics—namely the class interests of Muslim landowners, an insistence on preserving Bosnia-Herzegovina’s territorial integrity within the new Yugoslav state, and even concern for the autonomy of non-judicial communal institutions—fall almost entirely by the wayside. As if to underscore the point, Greble describes JMO leader Sakib Korkut on that same page as “a well-known Qadi” (i.e. a Sharia judge), but he was never even a judge at all; rather, to quote Karčić from the very page Greble paraphrased in the rest of her passage, he was “a journalist and theologian.”

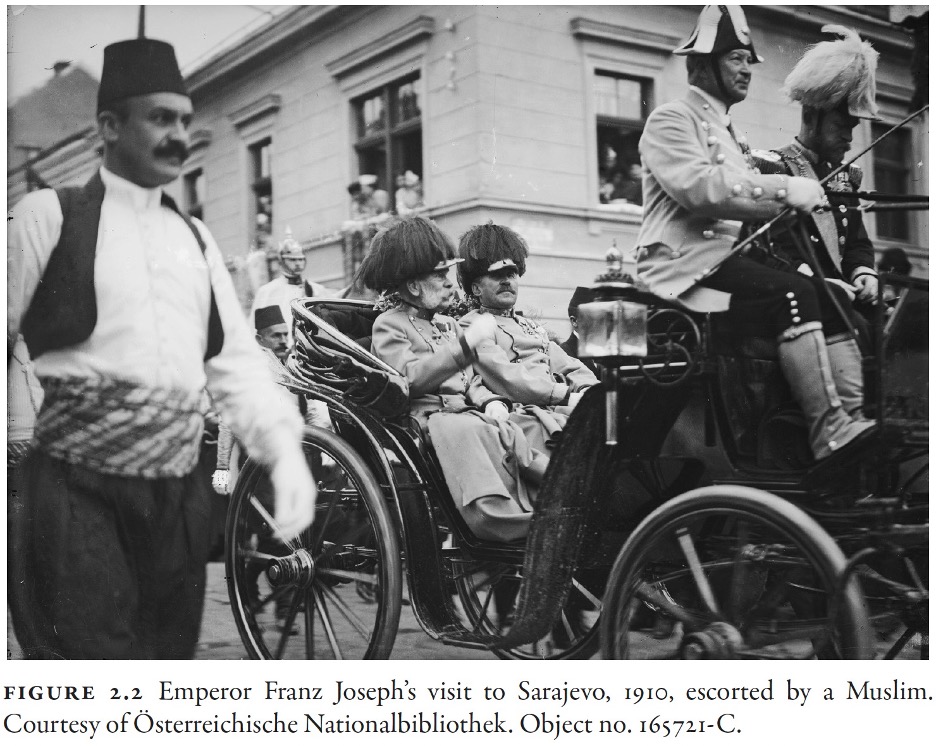

In the most charitable interpretation, this stretching of Sharia suggests an underlying ignorance of basic concepts in the Islamic tradition, which elsewhere in the text manifests itself through jarring misspellings of common terms and titles (e.g. the hitherto nonexistent “Mutivelj” in place of the Bosnian “Mutevelija” for a Waqf administrator, p. 67 and p. 140; “Arebevci” and “Arebevica” instead of “Arebica” for Bosnian-Arabic script, p. 77; “Natrag Islam” instead of “Natrag islamu”, p. 216). More troublingly, it fits a pattern in which the author chooses titillating, quasi-orientalist framings to draw in Western readers. After all, “Islamic prescripts” or “Islamic ritual norms” are far more boring than “Sharia,” a buzzword that far-right politicians popularized in the last decade across Europe and the US. In the same way, why bother grappling with the complexities of a term like “Mudžahid”—from the Arabic root ja-ha-da, roughly denoting a person who engages in a militant (but not necessarily armed) struggle for personal or communal betterment in accordance with Islam—when you can just casually translate the title of the eponymous journal in Sarajevo as “the Jihadist” (p. 241)?[48] This pattern extends to the book’s aesthetics, from promotional materials in which SHARIA is rendered in capital red letters, to the orientalist postcard serving as its cover (the third major publication on Balkan Muslim history by Western authors in the span of five years to focus the reader’s gaze on women in full-body veils), all the way to images and captions in the body of the text. One photo, in which the camera captures a blurry man in traditional Sarajevan Muslim folk costume walking by Emperor Franz Joseph’s carriage during the latter’s visit to Bosnia in 1910, describes the Emperor as “escorted by a Muslim,” attaching some orientalist pizzazz to an otherwise entirely nondescript figure lacking a name or context (p. 74).

Apart from the flattening of the discourse on Muslims and Islam, Greble’s insistence on the ubiquity of Sharia as the defining category of Balkan Muslims has another unsettling echo: that of the disappearance of Islam as a crucial factor in Muslim lives as soon as Sharia is no longer in (state) sight. In other words, when Greble describes “shutting down the Sharia courts and abolishing the position of Sharia judges’’ as an act of removal of “critical infrastructure through which Muslims practiced their faith” (p. 239), she is practically claiming that Muslims were losing any viable means through which they could ensure the continuation of their faith. This is further confirmed by her insistence that, with the social and political transformations that followed World War 2, “Islam ceased to be a legal issue and would be reformulated as a cultural idea’’ (p. 249). This string of reductions, from Islam as law to Islam as culture, comes dangerously close to the common Western academic stereotype of Bosnian Muslims as barely Muslim anymore, a claim popularized by Ernest Gellner in his famous quip from Nations and Nationalism that to be a Bosnian Muslim one no longer even needs to believe in God.[49]

Finally, it is worth noting how Sharia law features prominently not only in the book’s argument, but also in its marketing and wider acclaim. The book’s promotional materials thus emphasize that it is based on research in “both European and Shari’a law.” But this emphasis is perplexing in itself. Given the work’s focus on the legal history of Muslims in the post-Ottoman Balkans, this praise is akin to commending a history of 20th-century Quebec for utilizing sources in “both English and French”—surely something academic readers could expect. Bosnian and other scholars of the region regularly engage with documents from this era’s Sharia courts to no such fanfare, as they pose no exceptional logistical or linguistic barriers to entry. In that sense, while Greble deserves credit for visiting some of the region’s less-frequented local archives, her use of “Sharia” sources is, by itself, quite unremarkable. What would have been more noteworthy is if the author had exhibited a sophisticated understanding of both Western European and Ottoman-Islamic legal and intellectual traditions in interpreting these sources.

Agency and Dignity

If this were just another specialist study, the review could end here, having identified a number of tangible scholarly flaws. But “Muslims and the Making of Modern Europe” aspires to far more than specialist expertise, and, as such, deserves situating within its wider intellectual and political context as well. The book frames itself as making both a radical historiographical intervention and a dramatic stand on behalf of the Muslim communities under study. Its introduction stresses that these Muslims were “indigenous” and “European,” and closes, tellingly, with a paragraph making the case for their “agency,” which it ostensibly restores ().[50] Seeing as this “indigeneity” has not been a subject of serious scholarly dispute for at least a century, we can further infer that the book primarily aims for a broader Western audience and even some deeper truths about the place of Muslims—and, lest we forget, specifically Balkan Muslims—in Europe. But how, exactly, does it relate to the agency of its subjects, their descendants, and their actual relationship with Europe today? After all, if a book adopts the jargon of emancipatory scholarship, it seems only right to evaluate it in those terms as well.

Problems first appear on the level of primary sources. Reviews have praised Greble for extensive archival research that foregrounds Muslim perspectives, but for all the talk of such “Muslim voices,” the core of the book relies on materials from state archives: police reports, government documents, court records, correspondence with authorities, etc. Extracting Muslim perspectives from these sources poses obvious methodological challenges, but Greble rarely acknowledges them, and at times perhaps even reproduces the hierarchical power dynamics involved. The reference to a man named “Iljaza” in the opening line of the introduction, for instance, may well represent an orthographic mangling, since such a name is broadly unrecognizable to native speakers of both Bosnian and Albanian (p. 1).[51] Elsewhere, Greble draws on Muslim periodicals, but given the errors outlined earlier—the Biser chronology mixup, reductive typologies of Islamic intellectual currents in describing Hikjmet, etc.—it is not clear that she can reliably contextualize them. Finally, it bears repeating that all of these materials are in the local Slavic language (i.e. “BCMS,” or Bosnian-Croatian-Montenegrin-Serbian). There are seemingly no Muslim “voices” speaking Albanian or Turkish in the book, despite those being Muslims’ primary languages in half of its area of study. This is a fundamental flaw for a project purporting to restore the “agency” of the multilingual Muslim communities in what became Yugoslavia, but one that seemingly no previous reviewers thought to mention, with one award committee even praising Greble for her “multilinguistic” research.”[52]

Examining Greble’s relationship to the existing literature raises still further questions about this restoration of agency and oft-cited centering of Muslim “voices.” Of the 44 endnotes and 82 names cited in its introduction, “Muslims and the Making of Modern Europe” includes only 3 Balkan Muslim authors:…

Examining Greble’s relationship to the existing literature raises still further questions about this restoration of agency and oft-cited centering of Muslim “voices.” Of the 44 endnotes and 82 names cited in its introduction, “Muslims and the Making of Modern Europe” includes only 3 Balkan Muslim authors: Nusret Šehić’s 1980 study of the Muslim autonomy movement in Austro-Hungarian Bosnia-Herzegovina, Omer Behmen’s 2001 book on the Young Muslims, and an unnamed contributor to the JMO periodical Pravda from 1923. In the conclusion, 11 endnotes with 20 authors (12 of them new) yield 2 more: a 1945 letter by Sarajevan writer Šemsudin Sarajlić and a short 2010 piece by legal historian Fikret Karčić. In total then, the two sections of the book that directly address its place in relation to the existing literature reference just 5 Balkan Muslim authors across 55 endnotes and 94 distinct names, all 5 of them Bosnian.[53] 2 of the 5 are treated as primary sources and 3 as contributions to the literature, the latter thus amounting to 3.26% of all cited secondary works. Of these 3, Fikret Karčić is the only one credited as making a scholarly argument, barely four pages before the end (p. 258).

The remaining 2, like seemingly all other references to Balkan Muslim scholars in the book, serve to provide the author with raw empirical data for making her own original argument, a privilege apparently reserved for Western academics. Indeed, all other references to an “argument,” acknowledgments of “draw[ing]” on the work of others, and praise for studies as historiographically “important” (or “classic,” “pioneering,” “pivotal,” “seminal,” etc.) throughout the book’s 885 endnotes are just about exclusively limited to non-Balkan authors working within the Western academy.[54] We may perhaps reasonably expect scholarship emerging from a particular intellectual and linguistic context to privilege other works within that milieu, but Greble’s insistence on “agency” and “inclusion” endows these disparities with considerable irony. That Greble does not find the historical opinions of the Muslims whose agency she restores particularly relevant also emerges from one especially illuminating endnote in her conclusion, where she claims that “Nearly every book about Muslims in Bosnia… highlights the distinct ‘compatibility’ with European customs of the way that Islam was practiced in this region” (p. 318, n. 2). This is, of course, an unreasonable claim that only begins to make sense if we add such qualifiers as “in English,” “for a popular audience,” and “since the 1980s,” though even then with massive disclaimers.

In some ways, however, Greble’s approach to the literature in the Western languages is not much better. To begin with, Western here de facto means English. Of the roughly 250 items in the bibliography, there are a total of 3 secondary sources in either French or German. These include neither Philippe Gelez’s study of Bosnian Muslim national thought during roughly the same period nor even Armina Omerika’s definitive monograph on the “Young Muslim” networks so pivotal to chapter 9.[55] As for the “important” English-language monographs on Balkan Muslim history that do feature in the introduction, Greble’s solution is to herd nearly all of them into a single citation that ponders why they have remained “apart, marginal, [and] on the fringes” of the European history that really matters (p. 18, n. 13). The implication is that “Muslims and the Making of Modern Europe” stands apart from the entirety of its field in whatever language, somehow uniquely capable of conveying the history of Muslims in the former Yugoslavia as a “European” story—or, as one particularly colorful review put it, “repopulating” a “blank space” on the European map. In other words, the only thing readers learn about Greble’s work as it relates to previous scholarship on the same topic is that it will succeed where others have failed. This enviable self-belief seems to have extended to the review process as well: of some 36 scholars credited with reading drafts of the book in whole or in part in its acknowledgments, exactly one of them specializes in the history of Muslim communities in the former Yugoslavia, albeit with a focus on Albanian-speaking regions (pp. x-xii). As for Muslims in Bosnia-Herzegovina and the Sandžak, one is left to assume that Greble is the only expert needed there.

Rather than a concern isolated to the ivory tower, the book’s patronizing treatment of the existing literature directly connects to its wider political context as well. Take, for example, the previously mentioned critique of predecessors who “[came] to speak of a different kind of Islam existing in the Balkans, one that was inherently secular, Western, and compatible with European modernity” (p. 257). As a concrete example of how “nearly every book about Muslims in Bosnia” committed this error, Greble cites anthropologist Tone Bringa’s landmark 1995 study of Muslims in rural Bosnia, “Being Muslim the Bosnian Way.”[56] This is, however, a gross mischaracterization of Bringa’s work. The “Bosnian Way” in Bringa’s title is not an allusion to some distinctly “European” form of Islam, but a reference to how, as Greble puts it herself, “Islam in southeastern Europe was locally inflected and malleable” (p. 6). While the book does feature a section titled “Muslim Europeans”, this is simply a reference to an awkwardly titled 1975 monograph on “European Moslems” by William Lockwood, which studied kinship and local economy.[57] Bringa’s section itself situates her work in relation to the broader field of “Mediterranean” anthropology, pointing out that Muslim societies were not limited to the sea’s southern shore, but existed to its north as well. In other words, it centers on a geographic observation to counter essentialist notions in its field, rather than an essentialist claim in its own right. Significantly, Bringa’s broader engagement with “Europe” included a critique of the indifference and minimization that European powers employed during the then-ongoing Bosnian war, which saw Croat nationalist forces “ethnically cleanse” the village at the center of her book of its Muslim inhabitants.[58] In that sense, Bringa is representative of a generation of Western scholars of Bosnia who felt an intellectual responsibility to bring attention to the violence targeting their communities of study, many of them even taking personal or professional risks to do so.[59]

Greble’s own engagement with the genocidal violence of the 1990s and sense of scholarly solidarity with the issues facing her Muslim subjects today is altogether different. More specifically, it does not exist.

Greble’s own engagement with the genocidal violence of the 1990s and sense of scholarly solidarity with the issues facing her Muslim subjects today is altogether different. More specifically, it does not exist. Although the book’s conclusion brings its narrative up to the present, even addressing the collapse of state socialism, it somehow avoids any mention of the Bosnian Genocide or even the Yugoslav Wars as a whole (p. 257). These subjects, it would seem, are too passé for scholars aiming at the 21st century Europeanist limelight.[60] In one crucial way, however, the omission makes perfect sense: despite posing superficially applicable questions regarding Muslims’ place in “modern Europe,” the book has very little to offer in terms of the dominant historical and socio-political concerns of Muslims in the former Yugoslavia today.[61] Where Greble’s work frames their late 19th and early 20th century history as a relevant case study for considering present-day Muslim minorities in Western Europe and elsewhere, ex-Yugoslav Muslims’ collective experience over the past several decades has been defined in large part by their status as majorities in Bosnia-Herzegovina and Kosovo, whether quantified in censuses or imagined in alarmist propaganda. Islamophobia in the Balkans today is therefore closely bound with Bosnian and Kosovar sovereignty and statehood: the question is less how observant Muslims adapt to confessionally-neutral citizenship in European liberal democracy, more whether Europe is even willing to abide by these self-professed ideals when the citizens in focus are of predominantly Muslim heritage. In “Muslims and the Making of Modern Europe,” the latter question is entirely off the radar, though the author still finds space to repeat uncited Islamophobic cliches about “alcohol [no longer being sold] in the downtown area of several Muslim-majority towns” (p. 257).[62]

What are the actual socio-political circumstances confronting Greble’s Muslims in 2023? Here it is hard not to contrast the effusive praise and upbeat tenor characterizing the Western reception of this safely removed book with the utter destitution and threats of violence that have afflicted Bosnia-Herzegovina and Kosovo in the interim (and, indeed, Muslim communities in the Balkans more broadly). In the former in particular, a dysfunctional, US-brokered constitutional framework has combined with decades of neoliberal “reform” to produce one of the world’s worst brain drains.[63] German conservative Christian Schmidt, the country’s High Representative, further imposed changes to its Election Law in October 2022 that explicitly sought to curb ethnic Bosniaks’ already-circumscribed political influence, comparing himself to Austro-Hungarian Emperor Franz Joseph in the process (an echo of Habsburg “citizenship,” no doubt).[64] Then, in January, Serb nationalist separatists paraded militarized police through the suburbs of Sarajevo to commemorate the start of the Bosnian genocide, with convicted war criminals, French politicians, and members of a Russian nationalist motorcycle club with close ties to the Putin regime all making an appearance.[65] A similar cast of characters featured at Belgrade-orchestrated barricades in northern Kosovo in December, with Serbian president Aleksandar Vučić also recently scrambling fighter jets to surrounding skies while his regime’s racist tabloids continue to call for blood.[66] Meanwhile, European leaders such as Emmanuel Macron regularly refer to the two countries’ nominally Muslim majorities as primarily a security threat, while simultaneously utilizing Bosnia as a holding pen for predominantly Muslim refugees from Asia and Africa on the outskirts of “Fortress Europe.”[67]

Rather than a contradiction, we might productively consider this juxtaposition between self-satisfied Western academic discourse and Balkan political reality as two sides of the same coin. Greble frames her “defense” of Balkan Muslims as a counter against Islamophobic bigotry in the West (e.g. “Muslims are foreign to Europe”), but in doing so, she presents these discourses as the natural starting point, making her account (“Muslims are indigenous to Europe”) seem radical only by comparison to extremists. That is a low bar to clear. In today’s elite academic institutions, this crude Islamophobia represents a relatively easy target, as her book’s virtually uncontested plaudits demonstrate. In politics as well, High Representative Schmidt is happy to concede the similarly banal point that “Bosniaks should live [in Bosnia-Herzegovina] too.”[68] But confronting the workings and legacies of Islamophobia within these same academic and political power structures, particularly in regard to “European” policy toward the Balkans today, requires greater intellectual courage than simply declaring Muslims “indigenous.” It is here that Greble’s study is conspicuously silent despite the ample opportunities outlined above, proffering instead fuzzy generalities about inclusion into “Europe” and painting that unsubstantiated gesture as a revolutionary act. This inclusion parallels Western officials’ latest empty promises of EU membership for Bosnia-Herzegovina and Kosovo, a dead-in-the-water scheme that today only serves to disguise their apathy toward Balkan Muslims’ more tangible concerns over security and sovereignty. “Muslims and the Making of Modern Europe” will therefore no doubt find a comfortable place in the libraries of the US embassies in Sarajevo and Prishtina, even as their realist diplomats presently work to strengthen the hands of the Serb and Croat nationalist establishments pushing Islamophobic discourses and striving to tear Bosnia-Herzegovina and Kosovo apart.[69]

Bosnia and its Muslims have been a ready subject of many studies since the war, sometimes being a mere context for other issues at hand, and sometimes being placed in an ideological framework according to the agenda of a particular author. Greble’s book, however, takes a different tack: through its framework of “agency’’ and “empowerment’’, it gives the veneer of a feel-good story, which in essence does not depart much from long-standing orientalist depictions and fantasies of Muslims in the region. 45 years since the publication of Said’s “Orientalism,” Greble’s Muslims live in harems and staunchly defend their never-changing Sharia. At the same time, the states that kill them in droves grant them crumbs of rights, somehow amounting to a “citizenship” that then severs them from their coreligionists in the rest of the world. Muslims in this context are perhaps noble savages, but still savages to be tamed by benevolent post-Ottoman states. The final product is a comforting read, where Balkan Muslim history is repackaged for Western liberal consumption as an inclusive story of Muslim “citizenship” and legal adaptation in a bygone age, and where the Islamophobic violence inherent to ongoing imperial and ethno-nationalist projects in the Balkans appears incidental rather than closely bound with EU and US policy in the region. The unspoken hero of the story is the author herself, who, as per Said, renders evidence of this “extrareal, phenomenologically reduced… out of reach” Islamic realm “credible only after it had passed through and been made firm by the refining fire of [her] work.”[70]

In that sense, the key insight of Greble’s project rests less on any empirical findings or theoretical contributions than on the apparent fact that, despite at least 150 years of Balkan Muslim literature and scholarship on questions of belonging and the meaning of Europe, it requires the professional pursuits of a well-connected American academic for these Muslim “voices” to be worth hearing at all. But the fact that Greble’s claims of giving voice to Balkan Muslims have been not only left unquestioned, but rather uncritically embraced and depicted as groundbreaking, ultimately provides less an indictment of the author herself than the fields of Eastern European Studies and European History at large.[71] Here the decline in US area studies has paradoxically yielded the worst of both worlds: an academic job market still rigidly defined by geopolitical blocs, but along lines that have pigeonholed “Eastern Europe” into a “European” subfield and thereby helped consolidate Eurocentric perspectives. At the same time, market logic has devalued substantive expertise and traditional linguistic training in favor of “big second books” with bombastic titles that can draw easily quantifiable citations and general readerships. Certain remedies appear self-evident: award committees might consider giving more weight to unfashionably “narrow” regional experts than to “big names” and networks of influence, particularly when living communities and histories of “marginalization” are involved. At the very least, the academic output of local scholars and more junior diaspora should appear in English-language historiography as something more than a resource for extraction, featuring as partners in dialogue rather than academic paralegals. Bosnia; Ireland; Kosovo; Ukraine: all these and other sites can serve as case studies for how this is entirely possible, as well as how short the field can fall.

…the key insight of Greble’s project rests less on any empirical findings or theoretical contributions than on the apparent fact that, despite at least 150 years of Balkan Muslim literature and scholarship on questions of belonging and the meaning of Europe, it requires the professional pursuits of a well-connected American academic for these Muslim “voices” to be worth hearing at all.

If this field’s sudden discovery of decolonization in the wake of Russia’s reinvasion of Ukraine is to produce something beyond bullet points on tenure-track CVs, some more uncomfortable reckonings may also be in order, particularly regarding the positionalities and responsibilities of Western academics toward the communities they study. From this perspective, “Eastern European” and Balkan studies under the auspice of “Europe” have become something of a refuge for Western scholars who would prefer not to address their power relations and positionalities, since this predominantly white and Christian ecumene, seemingly outside the Orient, makes them feel at home. Racialized communities in these spaces then have to think twice before they dare tell their own stories or voice critiques, lest they be accused of “nativism” or “woke gatekeeping.”[72] But what gate is there to keep? Where Ottoman studies’ recent “Selimgate” represented the initiative of tenured faculty at Harvard, Chicago, and UCLA, this review has fallen instead upon three junior scholars on either the precarious margins of “Eastern European” area studies or outside of the formal academy entirely.