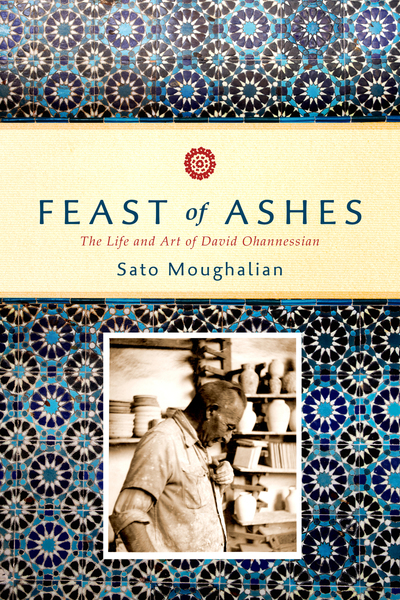

Sato Moughalian is one of those people who can do drastically different things well. She is, to my mind, everything a professional historian should be. Sensitive. Kind. Fearless. Detail-oriented. She’s also a professional flutist and is the artistic director of Perspectives Ensemble, which is a chamber group. She’s invested in documenting her people’s history, musical, material and more. We’ll be talking about, amongst other topics, her recent book, out 2019 from Stanford University Press’ imprint Redwood Press, about her grandfather, the artist, entrepreneur, and ceramicist David Ohannessian, Feast of Ashes: The Life and Art of David Ohannessian.

It was nominated for a Pen/Jacqueline Bograd Weld Award for Biography and was a finalist for the Prose Award in Biography and Autobiography. Feast of Ashes tells the story of David Ohannessian, the renowned ceramicist who in 1919 founded the art of Armenian pottery in Jerusalem, where his work and that of his followers is now celebrated as a local treasure. Ohannessian’s life encompassed some of the most tumultuous upheavals of the modern Middle East. Born in an isolated Anatolian mountain village, he witnessed the rise of violent nationalism in the waning years of the Ottoman Empire, endured arrest and deportation in the Armenian Genocide, founded a new ceramics tradition in Jerusalem under the British Mandate, and spent his final years, uprooted, in Cairo and Beirut. The book begins and ends with his granddaughrer, Sato Moughalian and her experiences as an artist and as a historian of this important narrative. Moughalian is now working on a second book.

Welcome to Knowledge and its Producers, a limited series from the Maydan produced by NA Mansour. In each episode, we’ll be talking to people who are at the forefront of knowledge production, typically away from the traditional educational power structures.

Sato’s Performances

https://youtu.be/DYmM-LE2-OA

https://youtu.be/0llYDha2x2o

https://youtu.be/3mxLlBcaFB8

Sato’s album Oror (With Alyssa Reit)

On Spotify

On YouTube

On Apple Music

TRANSCRIPT- Knowledge and Its Producers: Episode 1 – Sato Moughalian

https://themaydan.com/podcasts/knowledge-and-its-producers-ep1-sato-moughalian/

[Opening Music]

N.A. Mansour 00:02

I grew up going to artist workshops and galleries with my mom. There was an emphasis on craft and folklore as art in my life. One workshop we frequented every time we went to Jerusalem, which was so far yet so close to the village I spent most of my childhood in, was the Balyan family’s ceramic studio on Nablus Road. We collected pieces over the years and when I began to go to Jerusalem and Jordan, where another Armenian owned ceramics workshop exists, I would collect pieces for my mother. I went with a knowledge of the historical tragedies that brought the Armenians out of Anatolia into Palestine and Jordan, but not the specifics of the person who brought the ceramics that I grew up around. It was only recently that I learned they came from Kütahya, in Anatolia, to my corner of the world. I learned this from someone who is dedicated to documenting their peoples, their family’s, history. Someone who doesn’t draw inside the lines.

Welcome to Knowledge and its Producers, a limited series from the Maydan, produced by me, N.A. Mansour. In each episode, we’ll be talking to people who are at the forefront of knowledge production, typically away from traditional educational power structures. We will be talking to people who curate, who edit, who run research centers, who write and more. My field is Islamic Studies and we’ll be talking to people who fit into the study of Islam and the Muslim-majority world, sometimes, most of the times, but that doesn’t mean they’ll be Muslims themselves or Arab or Turkish. It just means that we don’t have perfect terms for describing this big intersecting world. Not yet. The goal is to get a wide variety of people talking about different ways of accessing history, ideas, and more; to uplift the people we’re interviewing, and inspire you.

Our first guest is Sato Moughalian. She’s one of those people who can do drastically different things well. She’s, to my mind, everything a professional historian should be. She’s sensitive, she’s kind, she’s fearless, she’s detail oriented. She’s also a professional flautist and is the director of Perspectives Ensemble, which is a chamber group. She’s invested in documenting her people’s history, be it musical, material, and more. We’ll be talking about, amongst other topics, her recent book out 2019 from Stanford University Press’s print, Redwood Press. It’s about her grandfather, the artist, entrepreneur, and ceramicist David Ohannessian. It’s called Feast of Ashes: The Life and Art of David Ohannessian. It was nominated for a PEN/Jacqueline Belgrade Weld Award for Biography and was a finalist for the PROSE Awards: Biography & Autobiography. David ohannessian, in 1919, founded the Art of Armenian Pottery in Jerusalem, where his work and that of his followers is now celebrated as a local treasure. Ohannessian’s life encompasses some of the most tumultuous upheavals of the modern Middle East. Born in an isolated Anatolian mountain village, he witnessed the rise of violent nationalism in the waning years of the Ottoman Empire, endured arrest and deportation in the Armenian genocide, founded a new ceramics tradition in Jerusalem under the British mandate, and spent his final years uprooted in Cairo and Beirut. The book begins and ends with his granddaughter, Sato, and her experiences as an artist and as a historian of this important narrative. Moughalian is now working on a second book. So, let’s get to know her. I guess to start, we can ask, what are you most excited about right now?

Sato Moughalian 03:45

Well, I’m hugely excited about something that I set in motion last year and then forgot about through the early part of the pandemic, but now it’s about to arrive and that is my brand new custom-made Brannen Flute, produced in Boston, which is going to come literally any day now. I’m a flutist, as you know, by profession and for a long time, I had been thinking about making a change to a modern instrument. After lots of mulling and consulting with colleagues, I decided to make the plunge and order a flute from Brannen. So, I gave them all my specifications and a big deposit, and then I forgot about it because the whole world turned upside down, but now it’s going to arrive and I have to prepare my home and prepare my thinking, my schedule, and my life to accept this new tool to make music and I’m super excited about it.

N.A. Mansour 04:48

Okay. I’m not a musician, so you’re going to have to bear with me. This is a really crude metaphor, but is it like a pair of shoes that you have to break in?

Sato Moughalian 05:00

Well, you do have to break it in a little bit. The flute is metal, in this case it’s silver and gold, and it has pads that are underneath the keys that you depress to produce the different notes. Those pads take a certain amount of breaking in, but the biggest thing is that each instrument is idiosyncratic and I have to learn where the pitches are exactly for each of the notes. At what angle do I blow the air into the head joint or over the head joint? How do I produce sound in the lower register or the very, very high register? So, these are all the intimate nuances of an instrument and it just simply takes time to get to know them because each flute is vastly different from every other flute, especially when you’re going, as I am, from playing on an instrument that was made in 1948 to an instrument made in 2020, with lots of technological advancements, there’s going to be a period of adjustment.

N.A. Mansour 06:06

I have so many questions because I never talked to my musician friends about these things specifically, but then again, I don’t talk to flautists often. I talk to you often, but I don’t talk to you as a flautist.

Sato Moughalian 06:21

We know each other in a different capacity.

N.A. Mansour 06:24

So, I have more questions. Is it common for people to play on, is this the right word, vintage instruments?

Sato Moughalian 06:33

It really varies from city to city, but in New York City for the last couple of decades, there’s been a big preference for vintage flutes made by the Verne Powell company, which is also in Boston. Boston is the geographic center of American flute makers. There was a big preference for these older flutes. The metals that they use, the silver alloys that they used, were different. The scale is different. The way sound resonates in the instrument is different. A lot of us felt like we could get a very beautiful sound from these old instruments, but they’re extremely temperamental. Before the pandemic, I used to travel a lot, so I loved my instrument very much, but it would be hard to be in another country and then find that all of a sudden I had a leak or some other kind of a problem with the instrument. I wouldn’t know any repair people in the vicinity and it was very problematic. So, after a long period of both loving my instrument and struggling with my instrument, I just decided that I wanted something that was much more reliable and that I would find the time, somehow, to make the adjustments so that I can make the sound of it my own personal sound, but now, of course, I have all the time in the world.

N.A. Mansour 08:04

Are you going to perform for your friends and let us in on the process of your transition? Are you going to retire the older flute?

Sato Moughalian 08:16

No, no, no, no, no. Oh, do you mean am I going to retire my old instrument? Or am I going to retire myself?

N.A. Mansour 08:24

No, your old instrument. Don’t please don’t retire.

Sato Moughalian 08:28

Of course not. I probably won’t because I love that instrument so much, but it has been difficult when I’ve been touring with it because there’s very little room for changes, variances, leaks. As I was mentioning, underneath the keys that you see, fluid is depressed to produce the sounds and there’s a layer of padding and then there’s a layer of a thin membrane, which used to be made out of fish skin. Now it’s an artificial kind of fish skin and what happens is when you play for hours and hours, the felt that’s inside will bloat and the key won’t settle properly. So, there’ll be a leak and there’ll be difficulty in either producing sound or the pitch will change or some other annoying issue.

With the new instruments, they have a different system, they use different materials. The old materials were part of what contributed to the very beautiful sound, but now we have to figure out how to adapt and from all reports, the brand and instruments are extremely reliable. Of course, when you get into an airplane, the air is very dry. You go to a different altitude and have to adjust. Of course, as a flautist, that’s really an issue. If I go to New Mexico or if I go to South America to one of the really high cities, it’s a completely different sensation, the altitude. Sometimes we don’t even have time to adjust. If the flute is generous, it’s a big asset for a flutist.

N.A. Mansour 10:15

It’s interesting to have a relationship with an object that is subject to these environmental changes. I always think about how I, as a historian, am changing things by writing about them, but I don’t aim to change them physically. I don’t aim to destroy manuscripts, but it’s just interesting to hear this. The closest relationship that I have with a physical object is my pens.

Sato Moughalian 10:52

I know that feeling. I’ve gotten very, very fond of this uni-ball roller pen. I don’t know if you know those. I think they’re made in Japan. I have to order them on eBay because they’re the only thing I really enjoy handwriting with. I have terrible handwriting, but I do like to take my notes by hand when I’m reading a book or something like that. I find it embeds things in my memory better if I’m writing by hand and this is my favorite pen. How about you?

N.A. Mansour 11:24

That’s a very long conversation because I’m a fountain pen geek. I brought two with me right now to take notes with and, right before this interview, I was looking at new inks to try. It’s how much I love the material culture around books. So, I’m using this beautiful American made ink that sheens red when you write, it’s blue, but it sheens red when you turn it up to the light. If you write on the right paper, because– see, whenever I talk to my family, my friends about this, they always go off glassy-eyed and are bored. Why would you ever think about the quality of the paper you write on? But it’s also part of my work and it’s something I think about a lot and I find it really nice to have this reminder of how important the physicality of things are. To transition back to you, one thing I admire about your musical career is that it’s so multi. We’re talking about the flute, but at the same time, there are all these different aspects to it, right? You perform, but you also record music, you organize around music and create events to educate people. I find your career to just be so Multivalent.

Sato Moughalian 12:58

That’s really kind of you. I would say that there are really two threads to my career. One is to play the flute and to play with other musicians and the other is to reunite music with the environments in which it’s been created because that’s the great vacuum. I felt it as I was learning how to play and learning about music. Music was so often separated from the circumstances in which it was written or the influences that were operating on the composers as they were writing pieces, so I’ve always had this urge to reunite those things, whether it was with my own group doing research and including aspects of that research in the rehearsal process, or just in general, trying to understand how art relates to its environment. I think it was that lifelong strong desire, or I could even say compulsion, that led me to my interest in understanding who my grandfather was and where he came from.

N.A. Mansour 14:11

Okay, before we go on, just because I know that we’re speaking to a very diverse audience, how do you pronounce your name and how do we pronounce your grandfather’s name, who your book is about? What’s your relationship with your name and with his name?

Sato Moughalian 14:26

I pronounced my name in the United States as Sato Mou-ga-lion. It’s really Sato Mou-gha-lian. There’s a sound in Armenian that doesn’t exist in English, so to simplify it for American English speakers, my family always just said Mou-ga-lian. My grandfather’s name is Davit Oh-a-nes-ion, spelled David in English, but Davit is the Armenian form of David. He introduced David when he arrived in British-run Palestine, when he Anglicised the spelling of it.

N.A. Mansour 15:07

Something I think a lot about is how we bend for other people. It’s something we do because of the times. We change how our names are pronounced and it takes some measure of stress off of us, but there are all these different layers to naming and how we go by our names.

Sato Moughalian 15:27

Yes. My name is exactly my grandmother’s name. Her name was Satenig Moughalian. Sato is the diminutive of Satenig, so my name is actually Sato. We see this so frequently. I’m thinking about my grandfather who was not only an artist, but he worked in the commercial sphere, so he had to make himself accessible to a wide variety of people whose native languages were all different. I don’t think it changed, in any sense, his view of himself. I think he was just trying to make himself accessible to others, which he was very good at doing.

N.A. Mansour 16:18

I think there’s something really poignant about the fact that his name is David on the front of the book and then throughout the book he’s Davit. I enjoyed reading the book so much because we begin and end with you. What that does is it colors the middle of the book. The middle of the book is this very careful history of your grandfather and the Armenian genocide, but you don’t refer to it as the genocide throughout the book. We’ll get to that in a little bit for different reasons. The book is also about ceramics. By calling him Davit, we’re reminded constantly that he, I’m reminded at least, that he’s your grandfather. I think that does a lot of work for you in terms of narrative.

Sato Moughalian 17:16

He is recorded in art history books as David Ohannessian. It was a very conscious choice to title the book using the name that’s internationally recognized for him and the name that he had on his business card since Jerusalem. Since the nine internal biographical chapters of the book rely very heavily on family narratives that were preserved by my mother and are, also, very much a work of memory as well as a work of history, it only made sense to call him by the name that he was known within his family.

N.A. Mansour 17:55

Let’s talk about the family aspect of it. How is it to write a project like this as a member of your family and what did you balance when you did that?

Sato Moughalian 18:10

I relied a lot on the records that have been kept in my family and my mother’s work before she died in 1995, transcribing all the oral narratives that have been passed down to her. We’re the product of many, many generations of memory within my maternal line. Of course, it’s a complicated thing and I wanted to make a contribution to the historical memory of my grandfather, so it was definitely a hybrid of taking these family histories, family narratives, but then doing a tremendous amount of reading over a period of a year to sort of be able to situate them in their historical context. Then, the last phase was the archival research and it turned out that there was a great deal of archival material that had never really been examined. The book took like 10 years, the last five years were really concentrated work, threading together all these disparate aspects of understanding who he was, but that was a conclusory because before I even began thinking about writing a book, I was contending with my lack of understanding of the trauma that had been passed down in my family and my own personal work to make sense of that.

N.A. Mansour 19:43

Was the book therapeutic for you?

Sato Moughalian 19:46

I think the book was a culmination of a long period of literally therapy, of reading psychoanalytic theory, of reading about intergenerational transmission of trauma, of doing the work that was necessary to construct an internal model of the world that was more functional than what I had before. After about a seven year period of that kind of work, I embarked on reading history so that I understood the circumstances that my family had survived and the mass violence that they had survived, the geopolitical violence and displacement. It’s been a very, very long trajectory, but it’s been extremely satisfying because I feel like I was able to fill in some historical gaps that have been left by art historians, but also come to some understanding of what my family had survived and to arrive at a feeling of pride for my grandfather’s persistence, my family’s persistence, and their survival.

N.A. Mansour 21:04

One of the things I enjoy the most about the book is that it’s a heavy book. I was surprised that I was able to read it as quickly as I did because the first day I read it, it was so difficult to read. You begin with the personal chapter and then you get into the more historical chapters and those 13 pages at the beginning are so heavy. Then, you get into this idyllic Anatolian childhood that Davit had and you begin with him running through the Hills and there’s some cognitive dissonance there, but also there’s this understanding of what’s lost and the layers of it. Of course, I won’t spoil the end of the book. There is a narrative that you go through and it was unlike many histories that I read where I know the ending of the story. I felt very on my toes reading this because I had a vague sense, knowing the history, what would happen and reading the blurb. Your family members are so beautifully fleshed out. They are characters. They’re not historical figures like in most books and I think what this does so well is you get a sense of the historical debates. Those are embedded into the history itself. The way you tell it is so delicate, but then you get these very human figures who can annoy you at times, can impress you tremendously, and each have different reactions to the events they go through. The whole time I’m trying to get to this because I feel so overwhelmed when I think about this book. I don’t know if this was planned, but I think one of the implicit arguments that you’re making is that all history is personal and that <inaudible> has to drive it, right?

Sato Moughalian 23:26

Yes, absolutely. That was kind of a revelation to me at some point in my life, that history is not a thing. History, or histories, are narratives that are constructed by the people who are writing them. There are so many different ways at it and, of course, I’m not a trained historian, but I’m a careful person. I’m a person who wants to make sure that anything I suggest or assert can be proven. It was important to me to complexify my family’s story, that it wasn’t just this happened, this happened and then that happened. I wanted to show or restore the humanity and the agency of all these characters, which is something that’s very often lost, on the personal level, in history books.

I was very fortunate in that I have my brother who has a wonderful memory and I have 14 first cousins on this maternal side. I interviewed all, but one of them, multiple times. I recorded the interviews and I transcribed them. They all went through their closets and attics and came up with amazing letters, memoirs that had been written, photographs, which of course contain so much information. Between the interviews and the documents, the material items, their own collections of my grandfather’s art or collections of other items that they had managed to keep in the family, engagement rings, and visiting cards, things like that, and the archival work, the reading, careful reading, of history, reading of contemporaneous memoirs to fill in some of the details. It was my goal to present them as full human beings, who had their strengths and their flaws. I think that’s the way my mother passed things down in the family. It wasn’t just this golden idealized story. The story of our family, like the story of so many families, is the story of human beings who have wonderful attributes and who have very natural human weaknesses.

N.A. Mansour 25:59

I really enjoyed your answer. I thought she was a really interesting person to follow around and I like the fact that, this is an introduction, she left things to you. It’s almost like she knew that you would do this project.

Sato Moughalian 26:17

I had no idea. I wish I had asked her more questions. She was really like a second mother to me. Most of the time I knew her, she lived in Washington D.C. and I would frequently go and spend a few days with her, then I would often do my own music research in the library of Congress. I would stay with her and we would talk and talk and talk and she was the historian of her generation. She would give me assignments, find this book or locate this piece of information. I think neither of us consciously thought we were going to do this because there wasn’t the internet. There wasn’t access to information as there is today or the ability to communicate with people in so many different parts of the world instantaneously, but I think, had she been able to foresee that, she either would have done it herself or would have assigned it to me? I view it as part of my legacy from her. She preserved, to the best of her ability, knowledge of her father’s work. She interviewed him in the last year of his life in Beirut and she wrote down the results of those interviews. She managed to keep this collection of documents, incredibly valuable documents, that had not been examined by art historians. They ended up coming to me. I view that as my legacy and my cousins, they thought that because I had gone on to a life in the arts, it would be a good thing to support me in my efforts. They have all been extraordinarily generous with their time and sharing the things that they inherited.

N.A. Mansour 28:08

I want to touch on a thread you just picked up, which is the art history element of it, because I’ll have to say, this is where we’ll bring in my own personal story, one of the things that made me so interested in your book is my own history. The fact that I grew up going to the Balyan ceramics studio –

Sato Moughalian 28:31

Yeah, on Nablus Road.

N.A. Mansour 28:33

Yeah, on Nablus Road in Jerusalem, partly because it’s so close to the US embassy. We would get up early. My parents would take us off of school to go to the US embassy to renew our passports or something. We’d go through checkpoints and then, afterwards, our reward was that we’d go get food, obviously, but before we do that, we would go to Balyan and we would go look at things. We would go where they have a window open in their studio, so you can watch them working. My mom collects art of all different sorts, what people call folk art, but we call art because it’s part of how our cultures produce art and my mom has a rather large collection of Armenian ceramics.

When I was young, we had Armenian friends, we knew Armenian, we saw churches frequently on our goings and comings around Palestine. The Armenian mass in Jerusalem was something you went to for Christmas. There were all these different aspects to it and I very much internalized that Armenians were part of our Palestinian landscape, like Assyrians, like we all were. It comes from my mom being Christian, too. There was this assumption that we just assumed that everyone was Palestinian and there are “sectarian” issues, but it was a big part of my childhood. Of course, I knew about the genocide and I knew about all these different things, but I didn’t know exactly how Armenian ceramics got to Jerusalem and the relationship between Armenian ceramics and what are known as Hebron ceramics now.

Reading this book, I knew when historical events were going to happen, so it wasn’t like I was holding my breath because I kind of knew what was going to happen to the people, but I did want to see how characters acted and reacted. Another thing I wanted to know was how did the ceramics get to Jerusalem? What were the considerations with foil and clay and color? Reading the book was like seeing my friends, seeing all these pieces that I’d seen before and realizing that your grandfather had a direct hand in this. It was phenomenal. So, I want to ask you, by way of that monologue, about the art history in this? The academic discipline? You’ve spoken to me about this before, that you’re making a major contribution here in art history. You’re correcting several assumptions.

Sato Moughalian 31:12

Well, I think that’s very generous of you. You’re an amazing person to have read the book because you bring so much to it already, but, just to give anybody who’s listening to this a nutshell, most listeners will probably know the best known of Anatolian Ottoman ceramics came from the town of Iznik by lake Iznik, where there were very rich supplies of all the kale, the white China clay, and the other minerals that became characteristic in the 15th and 16th centuries of Iznik’s ceramics. Iznik’s Ceramics were supported by the Imperial court through many commissions for tableware and for tiles. We know all this because the great mosques in Turkey are covered with Iznik ceramics and are very heavily influenced by Chinese ceramics that came through.

In the 17th century, that trade went into a steep decline and Kütahya was a secondary ceramic center, which had been functioning all this time, but really rose to the fore in the beginning of the 18th century with the near demise of the Iznik trade. Kütahya was, also, on a historic trade route, so there were lots of different visual materials coming through that were incorporated into the repertoire, the visual repertoire, of Kütahya ceramics. There were also many Armenians and Greeks, as well as Turks, who were working historically in Katakia. There were different lines of ceramics that were produced. There were some that followed along the styles and patterns of the Imperial ceramics that were produced in Iznik, but then there were these very different figurative and ecclesiastical, functional objects. A very wide range of objects: lemon squeezers and coffee cups were hugely prolific products of Kutahya. In the 19th century, along with the economic stagnation in the Ottoman empire and with the diminishment of Imperial commissions to Kütahya, the trade really stagnated.

It didn’t stop, but in the history books, 19th century Kütahya output became a black hole and people just would refer to it passingly. There were actually things going on and there were records that, again, hadn’t really been examined. There was a revival in the third quarter of the 19th century, and then, under the young Turk, there was a revival again after 1908. I should say there was an acceleration of the revival that was already in place in 1908/1909. Between this period of 1908 and the beginning, and even into the period of, the Great War, there was a huge amount of activity in Kütahya, which has happened outside the range of most of the people who had been writing about these artistic traditions.

Of course, I had certain records from my aunt from my grandfather about commissions that he fulfilled in that period. Then, once I started looking, I found a lot more and it’s interesting too, because the products of the Kütahya workshops in that period, we can actually see them all over Istanbul now. People don’t really know when they were made or what the origin was, who the people were who were making them. The story of my grandfather, his career actually, illustrated this trajectory. He owned one of the three workshops that were active in Kütahya in the period right before the First World War. He was arrested at the end of 1915, deported early 1916 to Aleppo, and then ended up coming to Jerusalem at the end of 1918.

Just so that the story doesn’t go on for too much longer, this art moved in his person. He had attained expertise, not only in the production of ceramics during his time in Kütahya, but because he also participated in the very, very active projects that were sponsored by the Young Turk regime to scientifically restore historic tiled monuments from the 13th century, from the Seljuk era into the Ottoman era. He had contact with all of these ceramics. He, like the people he was working with, examined them closely, figured out what materials were used, how tiles were attached to monuments, and all sorts of technical knowledge. So, when the time came for the British to contemplate making new tiles, producing new tiles for the dome of the rock, which was in a precarious condition by the time the British occupied Jerusalem, he was the person who came to mind. We might talk more about the specifics of that, but he contained this kind of technical and historical knowledge, which he transmitted specifically to Jerusalem.

N.A. Mansour 37:17

I finally found it. As you were speaking, I was looking for the green dome of the Mevlana Museum because I know that Konya was one of the places you went to research the book and it’s an iconic piece. It’s one of these moments that I had where I felt like I was, I don’t know how to say it, in the presence of your grandfather having seen these spaces and having spent time in Jerusalem and Konya. There were these moments and then there’s a moment in the book where you’re in Konya, it’s just so magical. I don’t even know how to put this stuff into words. It’s so tear-jerking and enchanting.

Sato Moughalian 38:07

It also shows us how material culture tells us much larger historical stories. By tracing my grandfather’s output, we also see what happens, for example, to the Armenian people and how this other wave of Armenians ended up coming to Palestine. Armenians had been there, historically, for a very, very long time, but many more arrived during and after the Great War.

N.A. Mansour 38:34

That’s another element of this that I get very emotional when I think about. When I engage with your grandfather’s story because there’s so many, especially your mother’s story, and I won’t spoil anything for the book because you want people to go out and get a copy themselves or borrow it from a public institution. The Armenian and the Palestinian stories are in many ways one, in many ways parallels because there are so many different Armenian and Palestinian narratives. I think seeing how material history is one way of telling these stories. The book is such a great micro history, it’s a material history, it’s a cultural history and it’s a family history. It’s all these different things wrapped into one and done really brilliantly. It is another way to tell us the story of what happened. This is where I want to talk to you about terms. Your family referred to it as the massacres, we refer to it now as genocide, the Armenian genocide. It’s such a sensitive question. How do you write about these things and how do you contend with the fact that your book is really another story of that event?

Sato Moughalian 40:11

It’s definitely a story of the Armenian genocide and, had it not been for the Armenian genocide, had there not been organized mass violence and forced migration of Armenians from the Ottoman empire, we wouldn’t have the Armenian ceramics of Jerusalem as we have them today. Of course, I have absolutely no hesitation about using the word. The word in my family and, my mother died in 1995, my mother, because she suffered from the lingering effects of two generations of forced displacement, clung to all the things that rooted her in the places where she had lived in, the places that she loved, the people that she loved. Since the word genocide was not coined until 1944, when the Polish Jewish jurist, Lemkin, came up with this word to encapsulate the state sponsored atrocities of the Nazi regime and directed episodes of mass violence, of cultural destruction, of forced displacement, of all horrors that we can think of, but since that word hadn’t really been coined during most of my grandfather’s life, she clung to the words that he used. This is true in a lot of Armenian families, that they called it the massacre. A lot of people called it the massacres, they called it the Holocaust, they call it the great catastrophe. There were a lot of words that were used, and it was as though people were reaching out and trying to find some way to wrap their minds around this concept, for which one singular word had not yet been invented, the word genocide. It’s the word that I use, but because the nine biographical chapters are not only historical, but they’re a work of memory, I chose to keep as much of the language that my mother had passed down to me as I could. As you see, there are archaic place names, spellings, and things like that. I spelled things the way they spelled them. I use terms and language that they used. I actually tried to make a point of not introducing any words that were coined after the periods that I was writing about to try to maintain a internal consistency with that style of storytelling.

N.A. Mansour 42:56

That’s something that I was about to note, the fact that you go from, if you notice, between the personal chapters and the historical chapters in the middle, the spelling changed and it wakes you up to the fact that you’re in a different world. I liked that as an orienting technique.

Sato Moughalian 43:14

I also address it in the author’s note on the very first page of the book.

N.A. Mansour 43:19

It’s very careful. I like the book. You and I will fight about this all day, but I think of you as a historian. I think you have the professional training, that’s what it is, to go into an archive and then be confronted by so many things and come up with a narrative, stringing it together, because that’s what the act of this is. This one has a very human heart, and I did want to get back to one of the things you said, which was you referenced the fact that your mother went through two generations worth of very disorienting forced displacements. I feel similarly about terms because I know my father never uses the word ethnic cleansing, or my grandfather never did with regards to Palestine. One thing my grandfather was probably a little bit more sensitive to is the fact that, to destroy any reference to it, to destroy a culture, to destroy a people is also to destroy the culture and that’s what genocide is. It attempts to destroy these other cultural elements and it’s very marked and careful in how it attempts to destroy documentation of what culture remained. I think that’s really the triumph of your grandfather’s story, that he brought this art and he was able to preserve it and, because of him– I wish the studio still existed, mostly because, if his studio still existed, certain things wouldn’t have happened. Maybe, I don’t know, but because of him, there are ceramics in Jerusalem and it’s become part of the city.

Sato Moughalian 45:22

It was a confluence of many different circumstances. The British already knew who he was because he had done a major commission for Mark Sykes, who was extremely well-connected. In the Sykes estate in Yorkshire, called Sledmere House, there’s a very famous room that’s been written about a lot that’s dubbed the Turkish room. That was entirely made by my grandfather. Although my grandfather never saw it, this was designed remotely and in cooperation with Sykes and his architect. Obviously Sykes met my grandfather several times in Kütahya, but they sent elevations back and forth and letters back and forth, and that documentation actually remains. Because of this really magnificent room that people can visit today at Sledmere House, many of the people in Syke’s circle, including Ronald Storrs, who would go on to be the military governor of Jerusalem, saw my grandfather’s work.

They understood that this art was still alive somewhere in the world. When they ended up in Jerusalem and they were contemplating restoration of the holy sites, a number of people remembered my grandfather. Of course, they didn’t know if he had survived what we now call the genocide, but he had through yet another incredibly fortuitous twist. Sykes, who went to Aleppo at the end of 1918 to establish a provisional British administration, re-met my grandfather and arranged for him to go to Jerusalem to consult on this planned British restoration of the Dome of the Rock. That’s how this art ended up coming to Jerusalem. It was so many strokes of luck and serendipitous circumstances. The fact that my grandfather had this wide ranging technical knowledge of Kütahya ceramics and how to run a workshop, the division of labor, and how to source materials. My grandfather maintained the traditional techniques, including the use of a wood-fire kiln until the end of his career in 1948. He may have been one of the very last people, if not the last one, to have come from this Anatolian tradition who continued using the wood-fired kiln until the end of his professional life. He grounded the glazes, using the minerals by hand, he did something in his ceramic making in Jerusalem, which I don’t see as much now, which was he combined the use of opaque and translucent glazes, which is something that gives tremendous vitality to Iznik ceramics from the peak period of their production. He was very historically aware and although, obviously, he didn’t reach the standard that the Iznik ceramicists had in the 15th and 16th centuries, he had that as a model, as an aspiration in his mind’s eye.

N.A. Mansour 48:54

Listening to you speak, I’m struck by the fact that you’re really the final link in this chain. Maybe not the final one, but you’re a link. You’re the latest link in the chain.

Sato Moughalian 49:04

There are a lot of Armenian ceramicists in Jerusalem, who are continuing to produce and evolve the art. The Balians and the Karakashians, but there are other Armenian families there as well.

N.A. Mansour 49:27

Sometimes, when I think about history, I think about the fact that if something happens knowing it happens, I get romantic about documentation sometimes. I’m also of the opinion that if something is lost, if a building is lost or if a document is lost, then that is its fate. I get very fatalistic, then I go back and forth between different spectrums of romanticism. That’s how my brain works. It’s another, not coincidence, but it’s another link in that all these chess pieces were set out and you were one of them moving forward and progressing the game by documenting all of this down and your knowledge of ceramics, so dense in itself, this isn’t just a family history. This is clearly something that was written by someone who understands ceramics. I think an element of that, if I can be so bold, comes from the fact that you’re an artist yourself and you understand the importance of inherently holding on to certain types of things.

Sato Moughalian 50:51

That’s true, but I definitely do not want to give myself too much credit. I’ll give it to my grandfather. The fact that he survived and that he ended up in Jerusalem through all these confluences of fate, you could say that his art, the art that he replanted there, became a new branch in post-Ottoman ceramics. There is that and then there is the other confluence of circumstances, of me trying to come to terms with several generations of trauma in my family, finding a more peaceful way to live and also being able to collect a really substantial amount of documentation relating to my grandfather’s work and also wanting to contextualize it after having spent a professional lifetime trying to contextualize works of art.

I was already in that mindset and then having the amazing gift of coming across large amounts of documentation from my grandfather’s hands, photographs that he had taken, glaze formulas that he had preserved, chemical formulas, design ideas, lots of pieces of paper that had his sketches. I gained a little window into how he thought and how he conceptualized because he died before I was born. He had plans for the workshop that he hoped to rebuild in Jerusalem after 1948. In the early 1950s, when he was in Egypt, he worked with an Egyptian architect, Hassan Fathy Bey, as he called him, who designed a new workshop that my grandfather hoped would employ up to 400 artisans. It’s this incredible amount of stuff that came together through the efforts of my cousins and, also, through the efforts of a lot of librarians around the world to actually help me find documentation. This was the consolidated effort of many, many different people.

N.A. Mansour 53:10

Yeah, you thank everyone so generously and acknowledge them, which not everyone does.

Sato Moughalian 53:15

You can’t work without librarians. It’s very, very hard when you’re doing this kind of archival work that is the result of piecing together tiny scraps of information from such disparate sources, like Ottoman trade journals. For some period of time, I was trying to figure out– My grandfather spent a few years, after his father died when he was 14 years old and before he went to Kütahya when he was 17 years old, working for an egg merchant in Eskişehir. I wanted to know more about eggs at that period in Ottoman history. I was going to Avery library at Columbia every day, the art and architecture library, and the librarians were very patient with me, but at the beginning of trying to figure out about eggs and the egg trade at that time, the main reference librarian there, I had gone in and had a little conference with her about it. I didn’t go to the library for a week because I was on tour or something and when I came back, she came, not quite shouting, out of her office when she saw me, but she came running over and said, “I’ve been looking for you. I’ve been looking for you, look at this trade journal. I learned so much about eggs in the last week.” I owe her a great debt of thanks. I owe Guy Burak and Peter McMagierski, the two Middle East area specialist librarians at NYU and Columbia who just went so far out of their way to help me collect the materials that I needed. I thank them in my mind every single day.

N.A. Mansour 55:02

I want to switch gears for a second because I think this connects to the book indirectly, which is your musical career, where we started this conversation. That was my first introduction to your work. You have an album of Armenian lullabies that you’ve adapted and that are set to the flute and the harp. I adore it. It’s so wonderful. It was really cool to read the book and see someone who wrote some of those lullabies turn up. It’s this full circle of you being– if people can hear movement in the background it’s because I’m holding the book and I’m thinking through it, it’s just so stunning and I love it. We can talk about that in a little bit, or I’ll say that in the introduction, it’s a physically beautiful book. I highly encourage people to look at the physical book because it’s so beautifully put together by Redwood Press, which is an imprint of Stanford university. Regarding the music, I see that album in particular as this act of documentation as well. It’s this act of preservation, but interpretation, and it comes back full circle with the book too, because there are many lullabies and there’s all these different layers of history to it.

Sato Moughalian 56:25

As you alluded, there’s a central figure in Armenian culture, Gomitas Vartabed. Gomitas was the name he adopted when he became a priest and Vartabed is an honorific for a learned celibate priest. So, Gomitas Vartabed was born as Soghomon Soghomonian in Kütahya in 1869 and spent his life transcribing. He did many things, but the thing he’s most remembered for is that he transcribed many village songs that were passed down through many generations, and perhaps even centuries, among the Eastern provinces of the Ottoman empire, the Armenian provinces. He collected them, he transcribed them, he studied them, he studied what we now call ethnomusicology in Berlin.

He spent some years kind of trying to study what were the Kurdish influences, what were the Persian influences, Turkish influences and try to sort all those things out and preserve the body of Armenian songs. He did this and then he was among the, at least, 250 people who were arrested all at once on the evening of April 24th, 1915, and then deported into central Anatolia. Most of them were killed. He survived, but he never really had artistic output after that. He spent the rest of his life in psychiatric institutions, both in Turkey and then, eventually, in France, where he died in 1935. He preserved this body of orally transmitted Armenian culture. Most of the people who were the containers of this knowledge were killed during the genocide, so he’s taken on an actual role as a musicologist, as a composer, as a theoretician, as a person who introduced Armenian music to European and other audiences during his lifetime, and he’s also taken on a symbolic role as a person who survived the genocide, but was silenced by it, although he lived afterwards.

Meanwhile, my grandfather met him several times when Gomitas came to Kütahya. My grandfather learned all of his songs. My grandfather taught those songs to his children and my mother taught them to me, so when it came to 2015, the hundredth commemoration of this catastrophe, I wanted to do something to honor the memory of all those people who had, as we say, fallen asleep. I recorded this music, but I also used my grandfather’s art to decorate the CD cover and all that. Inside the CD, there’s an inscription that comes from an Armenian funerary chapel, just outside the old city of Jerusalem that was uncovered in an archeological excavation. I believe it was 1894, but dates back to the fifth or sixth centuries, and on the floor of this chapel, there’s some mosaic that illustrates the 40 birds, as we call it. It’s a tree that has branches with beautiful birds and in the center of this tree, there’s a caged bird with the idea that the bird’s song, even though it is caged, goes up to God. The funerary chapel from all those centuries ago has an inscription that honors the souls of those Armenians. Only the Lord knows where they are and my grandfather used the motif of the birds throughout his life in Jerusalem. There are many pieces and tile installations incorporating this Armenian bird motif as it’s known, but since the origin of that motif was from a funeral chapel that remembered the souls of lost Armeniansm, it made sense to me to use that as a unifying element.

N.A. Mansour 01:01:03

You also enter these dialogues of what it is to be because I really, and I’ve had this conversation with you before, I think of you as a cultural heritage professional, that’s how I take everything that you do in my mind. I bring it together because I think of you as this person who understands these principles of this ethics of how to communicate the past and how to create something new as well. That’s not my box for you. The reason I like that title is because I don’t like thinking of you in a box. I think of Sato as this artistic and creative and ethical entity. My God, I’m sounding so new age, but anyway, tell me about you being the leader of a musical ensemble, Perspectives. Is it based out of Columbia?

Sato Moughalian 01:02:06

It was founded at Columbia in 1993, Perspectives ensemble.

N.A. Mansour 01:02:11

Tell me more about your role in it and, since we talked about Gomitas, do you have projects going on in musical heritage?

Sato Moughalian 01:02:24

Perspectives Ensemble was something I founded as a project. I founded it in 1993 with the idea that this group would present events that would feature the works of composers and visual artists in a historical and cultural context. It’s changed, it’s evolved over the years. In the beginning, we had pre concert talks and we’ve always had written materials. Now, what I’ve been trying to do is to embed all of that in our performances and our recordings. We have quite a few recordings. We have two that came out on the Naxos label that I’m very proud of that I led. So, because of COVID, we had to cancel a bunch of concerts and one of the foundations that supports us very kindly gave us a COVID emergency grant. We’re doing several different things with it. One of the things we’re doing is producing a video that we’ll drop on YouTube later in August of Sylvia Alajaji talking about Gomitas and talking about the construction of identity in the Armenian diaspora and what Gomitas’s role was. Some of the things that we talked about a few minutes ago, what Gomitas actually did, and also the role that he has come to play and how sites have a remembrance for Gomitas, sculptures of him, have also become sites of memory and mourning for Armenians, like a cultural figure that has come to stand for so many different things. I wanted to do the opposite thing with my grandfather. I wanted to restore the idea of his agency because I found that’s what’s so often just wiped out of history, as we were talking about earlier, that everybody’s either the victim or they’re patronized by the British mandate or whatever.

In all the writing about my grandfather, both when it comes to how to Kütahya ceramics are recorded by Turkish or British art historians and also how Jerusalem ceramics are recorded by Israeli and British art historians, it’s always, “the British wanted to do this and Ashby wanted to do this and Ronald Storrs was wanting to do this,” but none of those things could have happened without the person of my grandfather, without his historical knowledge and without his initiatives, without the involvement of the Mufti in Jerusalem, which is something that’s left out of the narrative almost entirely. I wanted to restore a sense of agency to him, his actions and I find that it’s just such a vacuum, an absence, a gap in a lot of historical storytelling. We come up with these short hands for how things happen. We say Lincoln freed the slaves, the enslaved people of the United States, which completely wipes out the huge and potentially even more important contributions of individual African-Americans in their own liberation. I feel like if I could do this in the character of one person, my grandfather, I feel I will have made a contribution.

[Music]

N.A. Mansour 01:06:09

Thank you for listening and, again, a big thank you to Sato Moughalian. You can follow her @SatoMoughalian on Twitter. You can follow me @NAMansour26 and you can follow the Maydan @themaydan on Twitter. The production team includes Micah Hughes and Ahmet Tekelioglu. You can follow Micah at @micahahughes, our music is by Blue Dot Sessions and be sure to subscribe or follow the Maydan on social media for upcoming episodes and more on the Maydan’s broad selection of podcasts.

[Music]