Ottoman history unveils certain characteristics similar to the early modern or modern European history, as leading Ottoman historians, including figures such as, Mehmet Genç, and the late Halil İnalcık and Rifaat Abou-El-Haj, affirm. For instance, Venice and the Ottomans used similar techniques in grain trade to make sure that large cities were supplied well and they both developed comparable strategies to deal with irregular soldiers and mercenaries. It is tenable, in other words, to make cross-cultural comparisons not only in economy, but also governance, political life and educational organization between Ottomans and their European counterparts, albeit the fact that they were different and distinct in their own worlds. This is because they encountered, borrowed ideas, interacted and influenced one another, especially increasingly so in the modern period. Hence, rationalism and public service, as well as inspection and control that characterize the modern state can be easily observed during the reforms that took place in the late eighteenth century and later period of the Ottomans.

“During the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries, the Ottomans experienced increasing challenges and threats in several realms, predominantly in military, economic and political fronts.”

Just as the French revolution had shaken up Europe from bottom-up, Selim III ascended the throne and initiated his “reforms” from top-down to replace the Ancient Regime with the New Order that he was envisaging. In addition, several reports presented to him, which were prepared by members of the Ottoman learned class, suggested radical changes in the mentality of the empire. These changes in socio-educational, legal and political order, and economic life coalesced with Sultan Selim III’s original ideal, albeit he did not foresee an abrupt cessation of the extant structures, he was decidedly convinced about the need for a new order, unlike former reform attempts or reports which sought to revitalize and constantly referred back to a golden era in the past.

During the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries, the Ottomans experienced increasing challenges and threats in several realms, predominantly in military, economic and political fronts. At the same time Europe was going through dramatic transformations fed by the rising expectations in the aftermath of Renaissance as the scholasticism of the middle ages ended and scientific revolution began to evolve. When the Ottoman intellectuals and governors envisioned of or planned “reforms” in this era, the only aim that they had in their mind was limited to restoring that golden age of the past, which, for the most part, referred to the Kanuni era. They, missed, however, the critical point that what had been successful in the sixteenth century was doomed to fail in this new modern era against Europe because this continent was not the same old Europe in terms of its socio-educational, scientific, and economic order.

Unlike Abdulhamid I, whose administration of military and state affairs had become numb and aimless towards the end of his era, Prince Selim had already gained a reputation for his capacity and enthusiasm to rule. When Selim became the sultan in 1789, administrators, soldiers, subjects and foreign ambassadors alike all vigorously welcomed him. More than a month after Selim came to the throne, he called for a general consultative council (Meclis-i Meşveret) to discuss genuinely and from various angles what really could be done to save the Ottoman Empire. It is argued that around two hundred leaders of the ruling class – scholars/ulema, judges and administrators, scribes and teachers, active and retired military officers and soldiers – attended this meeting and presented their observations and solutions. The discussions and statements continued for two days, and then the Sultan himself concluded the meeting by appealing to everyone to do their best to end the instances of oppression, corruption, injustice and inefficiencies in the Empire which had been cited during the Meclis.

“He asked from those present to write down their observations and analyses for reforms in the form of reports/lâyiha, promising to consider their proposals seriously and eliminate all conditions that would hinder the application of proposed solutions.”He asked from those present to write down their observations and analyses for reforms in the form of reports/lâyiha, promising to consider their proposals seriously and eliminate all conditions that would hinder the application of proposed solutions. He even promised to execute anyone regardless of how close that person would be to him if he would “dare to betray the state and the religion” by defying these reforms.[1] Apparently more than twenty reports/lâyiha were presented to the Sultan, based on the archival material that is available to us today.

A Case Study: Educational Landscape in Istanbul

The reports that were written by leading intellectuals and bureaucrats who participated in this consultative council not only outlined fairly detailed accounts of instances of inefficiency and corruption in their empire but also proposed comprehensive reform proposals spanning areas from socio-educational order to economics and literacy. They aimed to invoke a peaceful and collaborative but top-down transition from the ancient regime to the new order in the empire. Below, I provide a sample of socio-educational and cultural issues that appeared in these reports (from 1790s to the first years of 1800), and the proposed reforms[2]:

“My initial readings suggest that there were 179 madrasas in all of Istanbul –159 alone in nefs-i Istanbul and the rest in remaining areas such as Eyüp, Galata and Üsküdar. There were 2797 students residing in 2046 rooms.”

- Mosques have fewer worshippers and madrasas also have considerably fewer students in Anatolia and Rumelia. There exists a widespread disinterest in worship and education. It is hard to find, on the other hand, a person knowledgeable in fiqh/jurisprudence due to the prevailing ignorance everywhere (cehelenin istiabından…). Judiciary system and trial process are not trustworthy. Qadis take bribes.

- The solution that he offers is as follows: certain number of books (three to four thousand books), in Turkish, Arabic, and Persian focusing on grammar, logic, and Islamic knowledge and social subject matters must be published immediately and disseminated everywhere.

- Imperial decrees (kanunname) must be issued to make sure that quality of education and learning flourish in all mosques and madrasas. In addition, the language of imperial decrees are not understood in remote and rural areas, so they must be written in a plain language.

- Scholars and learned people must only be hired after sound and fair examination. No nepotism of any kind (no more of ulamazade or mevâlizâde practices will be allowed).

- Muftis, scholars/müderris and Qadis should not make special visits to or accept invitations from local leading notables or personalities other than in the case of Friday prayers and the two major festivals (Eid al Adha and Eid al Fitr/Ramadan). When they visit, they should behave ethically and speak only about religious and scholarly issues.

- Imams and their custodians, teachers in Sıbyan schools, professors in madrasas and Qadis should be monitored and audited once every three months.

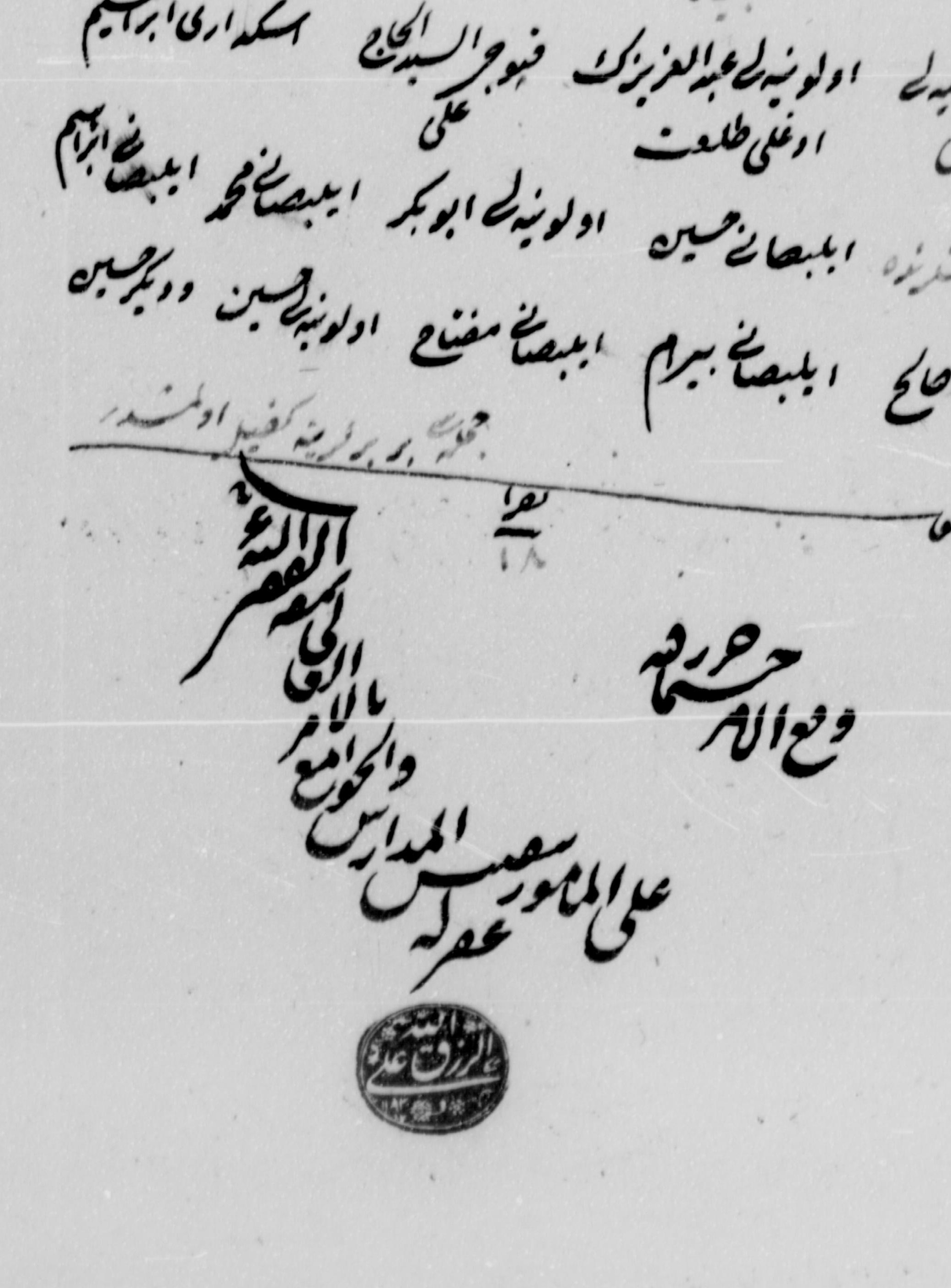

The foregoing discussion is a prelude to an attempt to analyze a register (defter) that I noticed in the Ottoman Archives (Bâb-ı Âsafî Defterhâne-i Âmire Defterleri (A.DVN.d) No 829) during my research nearly ten years ago as I was going through records and documents in the late eighteenth century while grappling with certain questions regarding this critical, early period of Turkish modernity. The register is dated 23 January 1792. It starts with a long introduction describing why and how this register is prepared. The defter then outlines all the names of madrasas in Istanbul including nefs-i Istanbul, Eyüb, Galata and Üsküdar. It contains the names of professors (müderris) who teach in these institutions as well as a list of students who attend them. When we carefully examine this document, we will notice not only that the names of professors and students are mentioned but also where they come from, and also whether students vouched for one another or not (kefalet). Those students who were not vouched for by a fellow colleague in a given madrasa were expelled along with all of their belongings. I noticed that almost all the professors hailed from Istanbul, Anatolia, Balkans and few from Caucasus, which suggests that the language of instruction in madrasas were in Turkish although the texts were in Arabic.

My initial readings suggest that there were 179 madrasas in all of Istanbul –159 alone in nefs-i Istanbul and the rest in remaining areas such as Eyüp, Galata and Üsküdar. There were 2797 students residing in 2046 rooms. The significant number of vacant rooms in certain madrasas is noteworthy.

Both the atmosphere of this document as well as the tone of the language and the content in the introduction of this register, aong with a thorough examination of its socio-political and historical context from interdisciplinary and comparative perspective, would help us hypothesize that features of modern state such as rationality driven reform, mobilization, inspection to serve the common good were in effect at this crucial phase of early modernization.

[1] A. Cevdet Paşa, Tarih-i Cevdet, (İstanbul: Matbaa-i Osmaniye, 1309), IV, 291. Cf. Seyfi Kenan (ed.), Nizam-ı Kad.m’den Nizam-ı Cedid’e III. Selim ve dönemi / Selim III and his Era from Ancien Régime to New Order (İstanbul : İSAM Publications, 2010), pp.13-15.

[2] Behic Efendi, Sevânihu’l-levâyih (Manuscript, Topkapı Palace Museum, No 270).