Following is an excerpt from Shenila Khoja-Moolji's forthcoming book Rebuilding Community: Displaced Women and the Making of a Shia Ismaili Muslim Sociality (Oxford University Press, 2023). A book forum with responses from Dr. Sumaiya Hamdani, Dr. Natasha Merchant, Dr. Shelina Kassam, and Dr. Shemine Gulamhusein will appear on Maydan in the coming months.

[Atlanta, Georgia, 2019. The phone rings.]

FARIDA, in Urdu: Hello, kaisay ho (How are you)? [Farida listens closely as Zarina, the woman on the other end, responds in a mix of English and Urdu.]

FARIDA: Yes, I will bring the application forms to jamatkhana and we can complete them together. If your application gets approved, you will then only have to pay $10 for your visit to the doctor. They will provide you medicine for free, and free visits to specialists, too. This service is provided by the DeKalb County, you see, and run by volunteer doctors. Let’s meet in jamatkhana. I will explain more.

[Farida returns to her cooking. That evening at the jamatkhana, she helps Zarina, who has recently migrated from India, complete the forms to enroll as a patient at the DeKalb County Physicians’ Care Clinic.]

ZARINA: Will you please take me to the clinic, too? My son works at the gas station all day and I can’t drive. There is no one to take me.

[Farida quickly reconfigures her weekly schedule in her head.]

FARIDA: Theek hai, no problem.

Farida gets up daily at 4:00 a.m. to drive to a nearby jamatkhana for morning prayers. Jamatkhana, a Persian word meaning community house, is the site of congregational worship and gathering for Shia Ismaili Muslims. After prayers, when other congregants have left this community house, Farida stays behind with a handful of other women to wash the objects used during rituals. Back home by 6:30 a.m., she prepares and packs lunches for her husband and son. Lunch is often a sandwich, but everyone wants something different: her seventy-year-old husband likes one piece of bread instead of two and fruit on the side; her son, in his mid-thirties, is happy with two slices and even some extra meat. Farida takes an hour-long nap, then leaves for work. Until 3:00 p.m., at a shop a few blocks from her house, she scoops ice cream, rings up customers, and makes cakes. Back at home, she cooks dinner so that it is ready for her husband and son when they return from work in the evening. She takes a thirty-minute nap and then heads out to drive sixty-five-year-old Zarina to the county’s free clinic. Farida tries not to miss the 7:30 p.m. evening prayers at the jamatkhana but sometimes, when the clinic is crowded with patients, she has to make that sacrifice. Farida says she is known in her local Ismaili community as the “baima (older sister) who helps newcomers get free healthcare”: “They think I am some healthcare worker [laughs].”

Sixty-one-year-old Farida migrated to the United States from Pakistan just over two decades ago. She made the move so her children could have a better chance at life, particularly access to a higher quality of education. Her family left behind a stable middle-class life in Karachi for Atlanta where, at first, they struggled professionally and economically in the unfamiliar environment. Members of the local Ismaili jamat (community) came to their aid: one woman helped Farida open a bank account; another helped her get a driver’s license; yet another introduced Farida to the Salvation Army where she could buy discounted furniture and directed her to a job opening at the local ice cream shop where she would work for the next two decades.

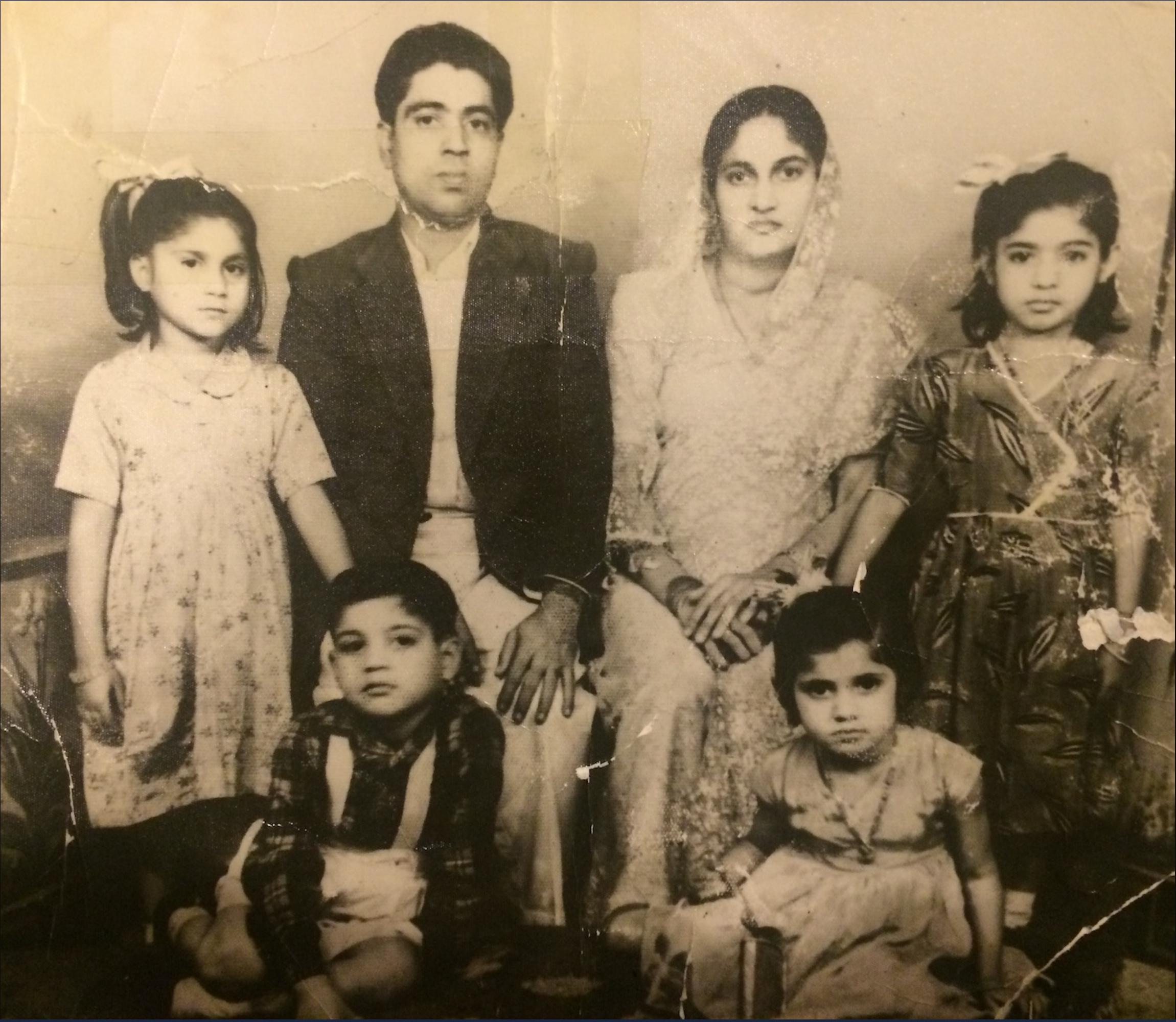

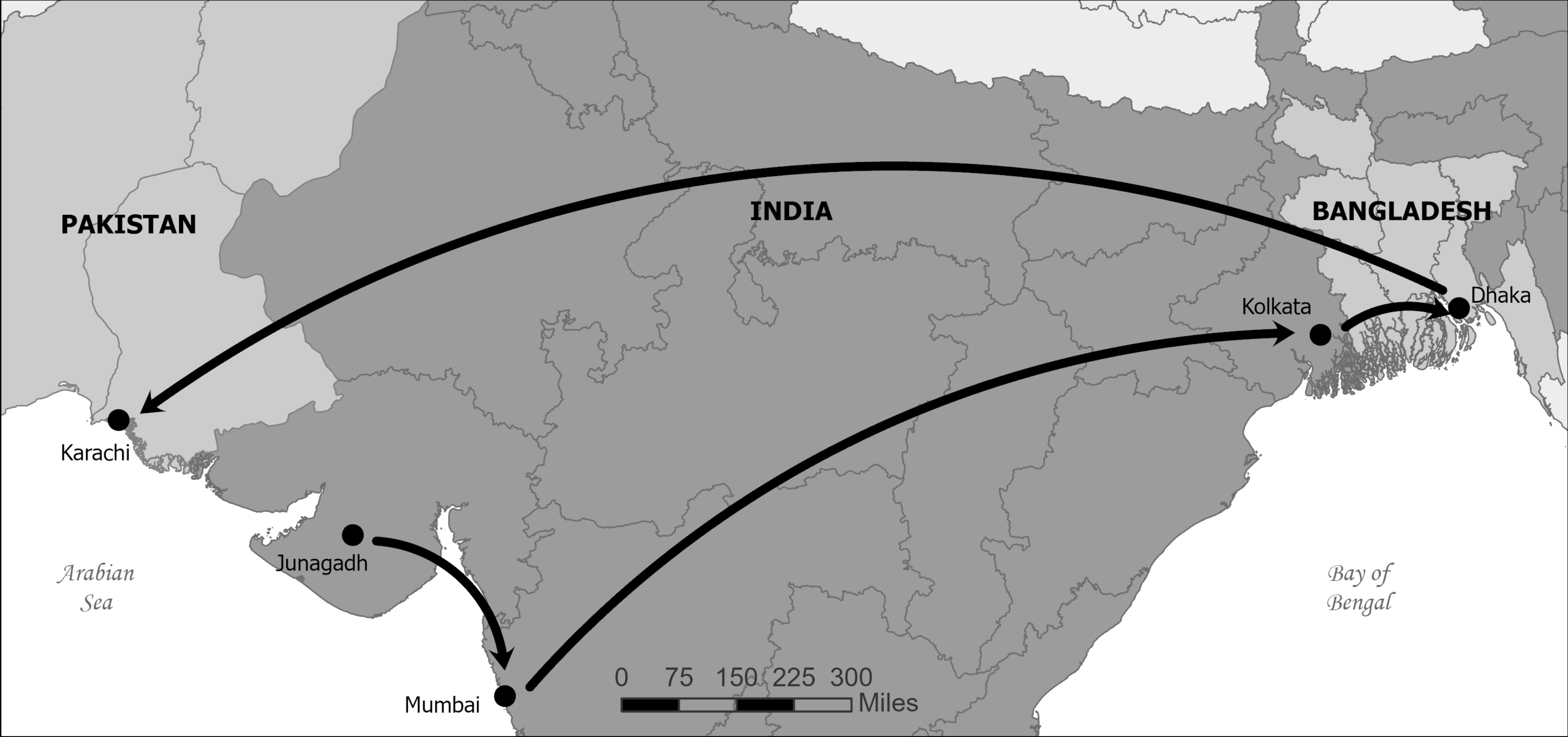

Her relocation to Atlanta in 2001 was not the first time Farida had benefited from such forms of community support. In 1971, as a twelve-year-old, she was displaced from her childhood home when East Pakistan (now Bangladesh) became a site of ethno-national war. She fled Dhaka with her mother and sister and found herself at a camp established by local Ismailis at a jamatkhana in Karachi. An ad hoc Ismaili volunteer committee came together to support displaced families like hers. The committee helped her widowed mother find housing and subsidized their rent for a year; a local Ismaili business owner offered her older sister a job, and the Ismailia Youth Services paid Farida’s tuition at an Ismaili-run boarding school (Figure 1). The Ismaili jamat of Karachi formed a protective web, an infrastructure of care, around this displaced family and saved it from sinking deeper into poverty.

There is a cyclical quality to Farida’s life story, and to her family’s story as well. Her mother, Shakar Juma, also lived through numerous geographic dislocations. Shakar was born sometime during the early 1930s into an impoverished family then living in the peninsular region of Kathiawar in western India. As the region was ravaged by famines, floods, and epidemics, Ismailis were advised by their Imam (spiritual leader) to move elsewhere in India or to East Africa. Shakar’s family migrated first to Bombay and then when she was in her twenties to Calcutta, where she married a day laborer named Juma Qurban Ali Chagani. Mounting tensions between Hindus and Muslims during the late 1940s and early 1950s, as the British colonizers departed, meant she soon had to leave Calcutta as well. This time, Shakar and Juma settled in Dhaka in East Pakistan (Figures 2 and 3). Juma found work at a chocolate factory, while Shakar did odd jobs. In addition to caring for their own four children, the couple was also responsible for Juma’s three younger siblings and his father. When Juma passed away of tuberculosis in 1963—while Shakar was pregnant with their fifth child—she suddenly had to care for the entire household. An Ismaili woman from her jamatkhana helped her find employment as a cook and housekeeper. Another, in 1965, facilitated young Farida’s admission to an Ismaili girls’ hostel. When in 1971 Shakar fled from Dhaka to Karachi with her children, including Farida, the cycle of vulnerability repeated—but so did, as we have seen, the cycle of care from members of her faith community. These acts of support reinforced the sense of affinity Shakar felt with other Ismailis and the reassurance she drew from her own faith: “Shukar Mawla (thanks to our Lord),” says eighty-one-year-old Shakar, who now resides in Karachi.[1]

Modern secular observers might interpret Farida’s efforts for Ismaili newcomers arriving in Atlanta as “paying forward” the generosity of those who helped her family through multiple displacements and forced migrations. But this framing fails to capture the spiritual and worldmaking dimensions of her actions. Perhaps slightly irritated at the need to elaborate on something so obvious, she explains to me, “It is seva. It is khidmat. This is what it means to be a part of the Ismaili jamat. It is how we make it possible for other Ismailis to find a place here [in the United States].” Seva is a Sanskrit word used to express devotion and service to a supreme deity with whom the devotee has a personal relationship, and the word khidmat is used by speakers of the Urdu language to express similar sentiments.[2] Among contemporary Ismaili Muslims of South Asian descent, seva and khidmat denote service to the Imam as well as to individuals and institutions of the Ismaili community and beyond. Farida’s invocation of seva/khidmat to describe her care for Zarina thus points to a set of spiritual commitments that exceed the idea of serial reciprocity conveyed by “paying it forward.” We instead see an ethical act of support that is set apart from expectation of exchange or calculation of ends. It is deemed virtuous in and of itself. Such everyday acts of care, from Farida’s perspective, help new migrants find a foothold in unfamiliar environments (Atlanta) while reinforcing affiliation with the Ismaili community (“This is what it means to be a part of the Ismaili jamat”). Ordinary ethics like these that respond to the experience of displacement are highly visible in the life stories of the Ismailis I consider in this project. But as I hope to demonstrate in Rebuilding Community, it has been the ongoing and pervasive exercise of ordinary ethics of care and support that has produced an Ismaili sociality beyond moments of crisis as well.

Farida is my mother. Rebuilding Community occasionally returns to her narrative but works more broadly to uncover the stories of care, help, and support that dozens of Ismaili Muslim women have extended to coreligionists against the dislocating effects of wars and forced migration. My interlocutors fall into two cohorts: one that fled East Pakistan in the early 1970s due to civil war, and the other that was forced to leave East Africa during the same time, when Idi Amin expelled Asians from Uganda and anti-Asian sentiments intensified in Kenya and Tanzania.[3] Although separated by thousands of miles of land and sea prior to these dislocations, the women in these cohorts share not only a religious tradition (Shia Ismaili) but also ethnicity and languages, as they trace their ancestors to the Sindh-Gujarat region in India. On leaving their homes in East Pakistan and East Africa, looking to resettle in West Pakistan (today’s Pakistan), England, Canada, and the United States, they began the individual and collective work of navigating the unfamiliar environments of new places. I follow the trajectories of these women and contemplate larger questions about the formation of religious community, women’s care practices, and placemaking after displacement.

I follow the trajectories of women to contemplate larger questions about the formation of religious community, women’s care practices, and placemaking after displacement.

Religious community is a repository of meaning and a marker of identity for many individuals, but it is not a given. Vered Amit and Brian Alleyne have suggested that we explain how community is empirically formed.[4] To offer the help she does to new Ismaili arrivals, for example, Farida had to learn to navigate the healthcare system of DeKalb County. She investigated the kinds of documents the clinic would require to offer financial assistance to patients. She began printing copies of forms and carrying them in her purse so she would have the right paperwork handy when someone in jamatkhana asked for help with healthcare. She maintains active connections with the clinic staff by remembering to give them gifts at Christmas. She makes phone calls to schedule appointments, drives fellow Ismailis to the clinic, and translates between Gujarati and English. She even learned some words in Farsi to communicate with new arrivals from Afghanistan. She listens intently to the women who come to her with their problems and provides emotional care in the process. And she offers these forms of support on days when she has also, as usual, sacrificed her sleep to clean the jamatkhana after morning prayers—sharing in a gendered practice to care for ritual space that, as we will see in the chapters that follow, has been central to building a sense of community for displaced Ismailis.

Such forms of care produce what Todne Thomas calls “spiritualized socialities” or communities that are bound together through a shared orientation to the Divine.[5] Relationalities like these can bridge and even transcend ethnic differences. Their salience is heightened in moments of dislocation as forced migration disrupts the bonds people enjoy to a fixed place, crucial to a sense of self and for accessing support. Anthropologist John Gray therefore sees the aftermath of displacement as a “predicament of emplacement.”[6] Care activities like Farida’s are particularly visible in these moments, not least because they have an emplacing effect. But when we study such practices of support undertaken by numerous women over time, we uncover a collective record that has bound Ismailis into a spiritual sociality or jamat, intergenerationally.[7]

While women’s labor of assembling community is central to maintaining religio-spiritual lifeworlds, this labor remains underappreciated and in its routine forms can be largely invisible.[8] Stories of support offered by women like Farida (and by those who cared for her own family half a century earlier) circulate primarily as family memories; they are not considered worthy of archiving within national or even religious histories. Relatedly, studies of refugee placemaking often narrow in on the contractual obligations between states and citizens and on the resources that the state or other agencies provide to displaced people.[9] Less attention has been paid to the labor that displaced people themselves undertake to rebuild their communities. The tasks of social, cultural, and spiritual reproduction—often performed by women—are comparatively absent as concerns of workforce participation take prominence.[10] By attending to the tasks of community formation as they occur in the context of displacement, we can deepen our understanding of the refugee experience; we can also use the heightened visibility of care work in displacement to better understand how that work supports spiritual communities during more ordinary circumstances. Indeed, while migrant placemaking is often about subjective attachment to a physical site, the book expands this definition to include a consideration of attachment to people and symbols as well, and situates those placemaking activities within the framework of spiritual acts that have more broadly defined and sustained the Ismaili sociality.

While migrant placemaking is often about subjective attachment to a physical site, the book expands this definition of placemaking to include a consideration of attachment to people and symbols as well.

The acts of care that I archive Rebuilding Community are not inevitable: Farida was not required to give Zarina a ride to the clinic, nor, two decades before, did the woman who took Farida to the DMV to get her license have to do so. While my interlocutors share ethnic and cultural ties, their expressions of care for each other cannot be reduced to these bonds, frayed after decades of living in the cities of the United States and Canada. Women’s actions instead spring from a shared religious covenant. Scholars have used the lens of spiritual kinship to describe such practices of religious community formation.[11] This lens is indeed helpful here, as the Ismaili Imams have frequently guided their followers to think of each other as brothers and sisters. Younger Ismailis often call older community members “uncle” and “aunty” even when not biologically related to them. But aside from these linguistic significations, we find another mode of subjectivation in the language of ethical conduct used by the Ismaili Imam(s). Ismailis regularly hear the Imam’s farmans in jamatkhanas where he instructs them to be kind to each other, to support each other by sharing what they have, and to care for each other as one family. Directives like these assert a normative force, keeping Ismailis orientated to each other. To explore the making and remaking of Ismaili sociality, then, entails examining a range of voluntary ethical acts that involve sharing time, knowledge, and material resources.

There is an ongoingness and ordinariness to this ethical conduct that extends beyond current analyses of Muslim charity and religiosity, which, as Amira Mittermaier observes, are dominated by “the hegemonic paradigm of self-cultivation.”[12] Ismailis practice their din (faith) both by working on their selves (their souls, bodies, thoughts) and by working intersubjectively to create community (cooking meals for coreligionists, visiting the sick, offering rides, storytelling). Of course, such modes of religious intersubjectivity are not distinct to Ismailis; Muslims globally engage in ethical community making. But unlike other Muslim groups, within Ismailis, the Imam acts as a centripetal force that gives this community a distinct route to ethical action. The Ismaili landscape of religiosity has a strong collectivist impetus that is sustained intergenerationally and transnationally, due in part to the Imam’s continuous guidance on interpersonal ethical conduct for community making. Identifying an Ismaili ethics of care is not to argue that the community’s particular understanding of spiritual obligation, honed in the diaspora, is wholly distinct from modes of care developed in other communities. It is, rather, a close examination of one manner of living a Muslim life in which members of other communities—or the scholars who study them—may identify points of commonality as well as difference.

The Ismaili landscape of religiosity has a strong collectivist impetus that is sustained intergenerationally and transnationally, due in part to the Imam’s continuous guidance on interpersonal ethical conduct for community making.

In the book I cover a large range of women’s activities, but reproductive work—such as cleaning jamatkhanas, cooking during religious festivals, assisting an elder with a bedpan at a refugee camp, and washing ritual objects—is a recurring theme. Even though such work is necessary for the propagation of society, it is generally viewed as a property of women’s biology and is therefore under- or devalued. Marxist feminists have consequently regarded housework as a quintessential site for gendered exploitation and have sought to demonstrate its value by moving it into the realm of waged labor.[13] Instead of pointing out the economic value of women’s work for the jamat (although there is certainly a basis for that), I reconceptualize this work in spiritual and relational terms, aligning with those feminist scholars who refuse to reduce women’s work to productivist logics.[14] I mobilize a different logic altogether, viewing women’s reproductive activities as producing sociability, repairing past trauma, and furnishing continuity from one generation to the next. This approach retains “care” as a useful framework for interpreting relationalities, kinships, and coalitions previously excluded from view. The challenge for me, then, is to emphasize the salience of care work, and the importance of those who undertake it, while also pointing out the circumstances and scenarios when it becomes a site of subjugation.

Ultimately, Rebuilding Community reframes the ordinary ethical practices of displaced women as the concrete spatiotemporal events that form religious community. In the process, we also learn about placemaking after displacement and re-evaluate care work. The book flashes back to their ancestors and pays a visit to their descendants to trace the transmutation of an Ismaili ethics of care. This broader view shows us that the jamat—and religious community, more generally—is not a given, but an ethical relation that is maintained daily and intergenerationally through everyday acts of care.

Pre-order Rebuilding Community with 30% off code (AAFLYG6) here.

Shenila Khoja-Moolji is the Hamad bin Khalifa al-Thani Associate Professor of Muslim Societies at Georgetown University. She researches and writes about the interplay of gender, race, religion, and power in relation to Muslim populations in South Asia and in the North American diaspora. Professor Khoja-Moolji is the author of award-winning books, Forging the Ideal Educated Girl: The Production of Desirable Subjects in Muslim South Asia and Sovereign Attachments: Masculinity, Muslimness, and Affective Politics in Pakistan.

Shenila Khoja-Moolji is the Hamad bin Khalifa al-Thani Associate Professor of Muslim Societies at Georgetown University. She researches and writes about the interplay of gender, race, religion, and power in relation to Muslim populations in South Asia and in the North American diaspora. Professor Khoja-Moolji is the author of award-winning books, Forging the Ideal Educated Girl: The Production of Desirable Subjects in Muslim South Asia and Sovereign Attachments: Masculinity, Muslimness, and Affective Politics in Pakistan.

[1] This interview was conducted in Urdu in January 2020. Shakar passed away in March 2021.

[2] Multiple Indic religious traditions mobilize the concept of seva to frame social action in relation to the guidance of gurus (teachers). On Sikh approach to seva, see Murphy, “Mobilizing Seva,” and R. Srivastsan, “Concept of ‘Seva’ and the ‘Sevak’ in the Freedom Movement.” For an intellectual history of seva see Kara, “Abode of Peace: Islam, Empire, and the Khoja Diaspora (1866–1972).”

[3] While “East Africa” encompasses a dozen countries in the eastern sub-Saharan region, in this book, it is applied more narrowly to Uganda, Tanzania, and Kenya.

[4] Alleyne, “An Idea of Community and Its Discontents: Towards a More Reflexive Sense of Belonging in Multicultural Britain”; Amit, Realizing Community: Concepts, Social Relationships and Sentiments.

[5] Thomas, “Rebuking the Ethnic Frame: Afro Caribbean and African American Evangelicals and Spiritual Kinship,” 226.

[6] Gray, “Community as Placemaking: Ram Auctions in the Scottish Borderland,” 40.

[7] Claudia Moser and Cecelia Feldman write about the effect of a constellation of practices over time in Locating the Sacred, 6.

[8] See Casselberry, The Labor of Faith: Gender and Power in Black Apostolic Pentecostalism.

[9] See, for example, Kuepper, Lackey, and Swinerton, “Ugandan Asian Refugees: Resettlement Centre to Community”; Muhammadi, “Gifts from Amin: The Resettlement, Integration, and Identities of Ugandan Asian Refugees in Canada.”

[10] Schiller and Caglar, “Displacement, Emplacement and Migrant Newcomers: Rethinking Urban Sociabilities within Multiscalar Power,” 21. Notable exceptions are the recent collection, Meyer and Van der Veer, Refugees and Religion: Ethnographic Studies of Global Trajectories, and Babou, The Muridiyya on the Move.

[11] On spiritual kinship, see Thomas, Kincraft: The Making of Black Evangelical Sociality, and Thomas, Malik, and Wellman, New Directions in Spiritual Kinship.

[12] Mittermaier, “Dreams from Elsewhere: Muslim Subjectivities beyond the Trope of Self-Cultivation,” 249.

[13] See Federici, Wages against Housework; Bhattacharya, Social Reproduction Theory; Duffy, “Doing the Dirty Work: Gender, Race, and Reproductive Labor in Historical Perspective”; Padios, “Labor.” On how unpaid work within the home is further divided into “spiritual and menial” and mapped onto racial lines, see Roberts, “Spiritual and Menial Housework.”

[14] I am influenced in particular by M. Jacqui Alexander and Sandy Grande’s work. Alexander, Pedagogies of Crossing: Meditations on Feminism, Sexual Politics, Memory, and the Sacred, and Grande, “Care,” in Keywords for Gender and Sexuality Studies. See also Raghuram, “Locating Care Ethics beyond the Global North”; Ritchey, Acts of Care: Recovering Women in Late Medieval Health.