Introduction

There is a color line in the Muslim world. How and why? While there are multiple forms of racism based on notions of color and ethnicity that exist within the Muslim world – such as anti-Amazigh, anti-Roma or anti-Desi racisms – anti-black racism is notable. It may not be exactly the same as the color-line stemming from the West, but it shares unsettling similarities. From North to South Africa; West to East Asia; and across Muslim diasporas in Europe, the Americas and Australasia; anti-black racism is a hardened social reality within the modern Muslim world. Anti-blackness, in the sense of racial discrimination based on one’s dark or black skin color, is something that precedes European colonial expansion in the Muslim world, whose relative boundaries traditionally laid between vast territories of what we now call Europe, Africa and Asia.

“There is a color line in the Muslim world. How and why? While there are multiple forms of racism based on notions of color and ethnicity that exist within the Muslim world – such as anti-Amazigh, anti-Roma or anti-Desi racisms – anti-black racism is notable.”

However, the pre-modern (meaning, pre-European conquest) form of this racism was not necessarily the same as its current post-colonial form, nor was its logic irreconcilably different from past manifestations. Studying anti-blackness in the Muslim world in a neat and clear way is complicated by the fact that Orientalist scholarship on this topic has attempted to white-wash the hands of the West’s anti-black racism by blaming the East for also being racist. On the other hand, peoples from within the Muslim world have been reluctant to unapologetically grapple with the matter head-on. In this article, I briefly present a broad framework for developing a more critical post-Orientalist and post-apologetic framework for addressing anti-blackness in the Muslim world.

Orientalism – White, then Black

Palestinian-American social critic Edward Said is credited with popularizing and framing the meaning of Orientalism. In short, Orientalism is the way in which the West has viewed, written about, and interacted and gone to war with the non-West from a racist Eurocentric position. While it was elite white Western scholars, politicians and military personnel who initiated Orientalism, it wasn’t long before those in the Rest internalized this colonial view of their own life-worlds. One of the ways this has manifested in African and African diasporic communities is through a phenomenon that has been termed Black Orientalism. Scholars such as the Kenyan-born Pan-Africanist Ali Mazrui and Black American Sherman Jackson have dealt extensively with the theoretical and practical ways this Orientalist understanding has embedded itself in the knowledge structures and practices of Africa and its diaspora. From debates on the naming of slavery in Arab, Asian and African societies, to Islam being reinterpreted as a “colonial” religion in Africa (strikingly similar to the way Hindutva has made Islam a foreign “colonial” religion in South Asia) – and across the political spectrum of Pan-Africanism, Black Christian Zionism, liberal civil society movements, Afro-pessimism and even the secular Black Left – Black African Muslims and others have long challenged the ways in which these debates have been influenced by ahistorical Orientalist frameworks.

“Studying anti-blackness in the Muslim world in a neat and clear way is complicated by the fact that Eurocentric and Orientalist scholarship on this topic has attempted to white-wash the hands of the West’s anti-black racism by blaming the East for also being racist. On the other hand, peoples from within the Muslim world have been reluctant to unapologetically and critically grapple with the matter head-on.”

Anti-Blackness in the Muslim World – Then and Now

On the other hand, save few marginal instances, the attempt to engage in understanding – let alone confronting – anti-blackness within the Muslim world has been largely apologetic. The constant argument that Western racism is different from Eastern forms of racial hierarchy (whether pre-colonial or post-colonial) is correct in sidelining the Orientalist critique. Yet, such an argument is insufficient with regards to critically analyzing the very real anti-black racism that has existed in various forms throughout the Muslim world’s history. From a certain standpoint, it is understandable that the Muslim world is reluctant to critically engage this issue, given that its life-world is already marginalized in relation to the capitalist Western supremacist world-system. Dealing with one’s dirty laundry – or what we might call the “margins of the margins” – is always tough, especially when the Orientalist boot that stepped on your neck is weaponizing that very issue of internal margins to continue war, genocide and neo-colonialism against you. Yet, from a perspective of sensitive and strategic multiple-critique, the question of anti-black racism – especially when it has become planetary – has become more urgent than ever. The importance of going beyond apologetics as well as Orientalism is key, and the tools for analyzing this anti-black condition must come from a more rigorous toolbox, given the multiple forms of knowledge and power structures confronting those on the margins and on the margins of margins.

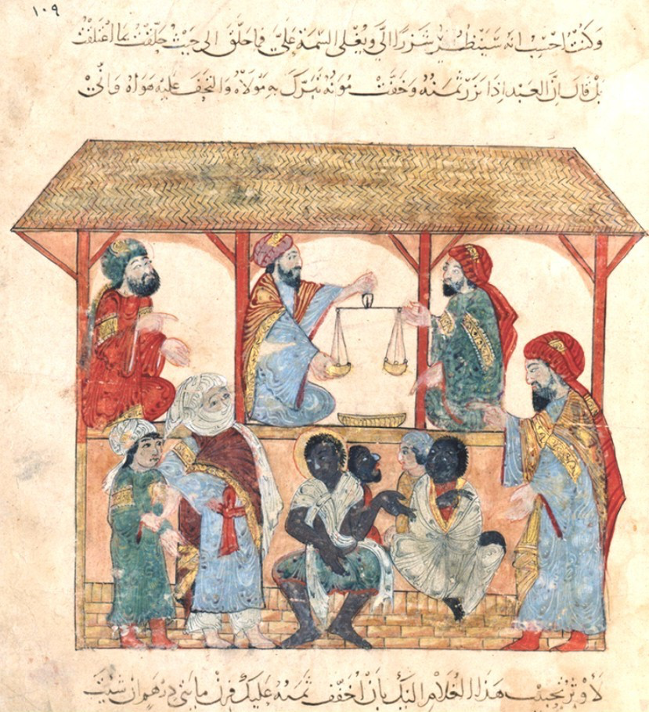

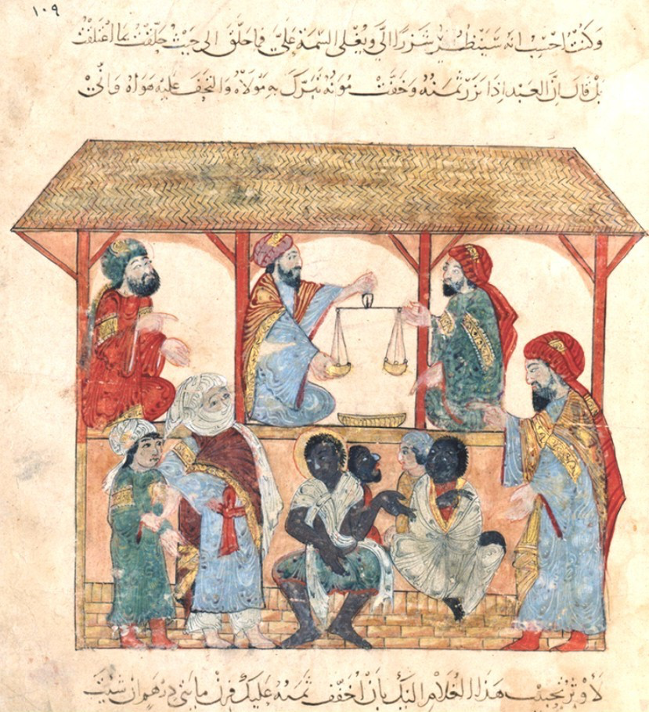

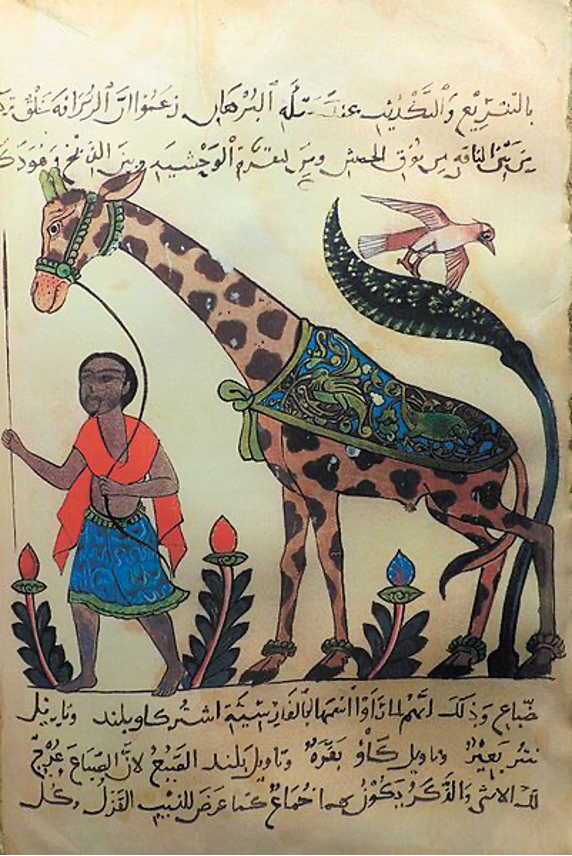

The difficulty in understanding pre-modern anti-black racism in the Muslim world is complicated by the seeming contradictions one faces when examining Islamic history. The clear anti-racist message of the Qur’an and Prophet Muhammad’s life is supported by the exaltation of a former black Arab slave – the famed Companion to the Prophet, Bilal ibn Rabah, to the metaphoric vox deus and official muezzin of the early Muslim community, and later senior military commander. Yet, within that very story is another companion of the Prophet, Abu Dharr, berating Bilal with a slur for having a black slave mother. Al-Jahiz (d. 868 CE) was a famed black Arab Muslim polymath whose influence on Islamicate knowledge production is regarded as highly authoritative and historically unique. Yet, al-Jahiz also wrote a book defending the virtues of black peoples against the anti-black discourses and practices he encountered during his time. There is also the example of blacks being enslaved for military and domestic work from Al-Andalus/Morocco to Ottoman lands, Southern Iran, and even the Indian coast. At the same time, black statesmen, generals, prominent scholars and everyday people in these very same places existed as dignified individuals and fully as themselves. Islamicate civilization in Sudanic Africa, or Bilad al-Sudan, is a testament to the ways in which Islam in what we now call Africa flourished. Sudanic Africa attained a high level of civilizational organization in an indigenous way without a systemic external imposition of said civilization coming from so-called foreigners like Turks, Arabs or Persians.

Individuals within the interregional world-system of Bilad al-Sudan have also consistently offered responses to the racism they faced when travelling to other lands in the Muslim world. Like al-Jahiz, scholars such as Ahmad Baba al-Timbukti (d. 1627 CE) and Ibrahim Niasse (d. 1975) engaged in critique of non-black Muslims who perceived them as inferior. The contradictions between what resembled a type of post-racial multi-culturalism alongside the many instances of sustained and less sustained forms of anti-black racism presents a quagmire for those who want to understand anti-black racism in the pre-modern Muslim world. It is a paradigm that is very different from the modern Western forms of anti-blackness, yet still shares with it in some theory and practice. In the modern period, the color-line hardened with the explicit and implicit importing of Western-derived theories and practices of anti-black racism. The millennia-old indigeneity of black peoples in North Africa, the Levant and the Gulf, for example, has been erased in mainstream consciousness due to Eurocentric nationalist narratives and geographies that created binaries along the Saharan desert and Red Sea that had not existed in the same way in the past. These modern forms of anti-blackness have both added to and subsumed the pre-existing prejudices in various regions which had earlier been less systematic or even non-existent.

Regarding the naming of anti-blackness in the pre-modern Muslim world as racism, one might argue that the term “race” is an inadequate tool of analysis for describing pre-modern forms of color-based prejudice or ethnic othering. Some scholars of race and religion have argued that the term “race” has roots in a specific racial science developed against Jews and Muslims in the 15th century Hispanic conquest of Al-Andalus, which was then exported to the Americas and Africa post-1492 against the Black and Indigenous populations. Such a position would caution using the term to describe phenomena outside said genealogy. However, the genealogy of the terms “race” and “racism” arguably have multiple origins, and have simultaneously been used alongside terms such as “genus”, “prejudice” and “ancestry”, depending on time and place in both the modern and pre-modern worlds. Contrary to the traditional Western Left’s dogma that racism sprouted from capitalism, Cedric Robinson long ago pointed out in his seminal work Black Marxism that medieval Western Christendom’s pre-capitalist racial hierarchies directly informed the ways it conceived of capitalism, and the way it exploited communities inside and outside of modern Europe through capitalism. In effect, Robinson argues that race and racism should not only be interpreted as modern phenomenon, but that we be attentive towards shifts in their modern meanings and to their newer attachments to modern systems of domination and control. In using the term racism to describe anti-blackness across various contexts and time periods in the Muslim world, I similarly attempt to differentiate its meaning and structural function in various contexts.

Key Similarities – Important Differences

Pre-modern forms of anti-blackness in the Muslim world shared differences but also unsettling similarities to modern anti-black racism. Among their similarities, anti-blackness in the pre-modern Muslim world contained within its ideological repertoire: Aristotelian theories of natural slavery, the Hamitic myth, actual systems of enslavement, geoclimatic racial determinism (derived from the ancient Egyptian and Greco-Roman Mediterranean-centric worldview), and even racist anti-black tropes in popular literature like One Thousand and One Nights (itself popularized and plagiarized by Orientalists though admittedly many of the stories were indigenous to the Islamicate world). However, a key difference is that this pre-modern form of anti-black prejudice formed in regions without the existence of totalizing modern nation-states and their panoptic governmentality. Simply put, power (and race) worked differently under pre-modern Islamicate empires, and was nowhere near as penetrating in the everyday life of the citizen-subject or the relatively self-autonomous communities who remained outside the reach of centralized non-capitalist polities. Thus, we should hesitate to call anti-black racism a primary organizing principle in these pre-modern Islamicate societies.

As Blackamerican Muslim scholar Abdul Hamid Ali argues, these societies were not primarily organized by race, nor, unlike the West, was the Muslim world a globalized world-system. Following Mexican-Argentinian philosopher Enrique Dussel’s decolonial historiography of the rise of world-systems from ancient Egypt to the modern West, what we might be able to say is that anti-black racism existed in sub-systemic regional or inter-regional systems in the Muslim world of the Mediterranean, Africa and Asia. Pre-modern forms of anti-blackness are arguably not trans-historical and trans-regional in the way modern anti-blackness has progressively hardened over five-hundred years of colonialism, slavery and capitalism. It seems anti-black racism acted as a secondary or tertiary social organizing principle in various historical Islamicate societies, and as a relatively “weaker” sociological form of anti-blackness. By “weaker” I do not mean to suggest it less violent, or apologetically reduce it to something morally “better” or “nicer,” but weaker in the sociological sense that it was not a form of anti-blackness that necessarily penetrated the everyday lives and world-systems which existed in the pre-modern Muslim world, nor was it able to manifest in an immanent totalizing form. In philosophical terms, modern Western-derived planetary anti-blackness is ontological while pre-modern Islamicate anti-blackness seems to be more ontic. Pre-modern anti-blackness in the Muslim world was not necessarily a concrete anti-blackness written in stone like the modern type. It seems to be more of a floating anti-blackness that could be accessed and commanded in greater or less capacities – or even non-existent – depending on time or place.

From a historical materialist perspective, even a system like slavery was not a primary mode of production in the pre-modern Muslim world, nor was its existence exclusively anti-black for the vast majority of its (ongoing) history. That is a very different context from the modes of production in the post-1492 Americas which relied fundamentally on anti-black chattel slavery and capitalism through Europe’s voyeurs across the Atlantic. It was not until the 19th and 20th century, for example, when the globalizing capitalist economy demanded more commodities from certain industries in the Gulf – namely the date palm and natural pearly-farming industries – that there was a massive uptick in enslaving black peoples. These effects are still felt today by those populations in the Gulf who are called racial slurs, such as ‘abd (slave), by all facets of society. The tributary mode of production was arguably the primary mode of production in the pre-modern Muslim world, alongside peripheral sub-systems of petty commodity and slave modes of production. None of these modes of production were fundamentally or exclusively anti-black for most of their history, yet they could in part demonstrate anti-black racism in certain inter/regional systems and in certain epochs. Anti-black racism – whether in the structural or superstructual sense – only starts to become a primary organizing principle during European colonial expansion in the Americas from the 16th century onwards, and then globally by the 20th century, including in the Muslim world.

Beyond Orientalism and Apologetics

To move beyond apologetics and Orientalism is necessary for producing a post-apologetic and post-Orientalist reckoning with anti-black racism in the Muslim world, past and present. There are three lessons to learn in this move towards a post-apologetic, post-Orientalist future: 1) we cannot understand a non-Eurocentric past only through Eurocentric eyes and tools of analysis, especially ones that reproduce racist, Zionist and Orientalist narratives about Muslims, Africans and others; 2) we must acknowledge that the pre-modern form of anti-blackness in the Muslim world is strengthened and subsumed by modern anti-blackness in ways new and old; 3) we must rebuild the historical archive of black peoples in the Muslim world, and fight to include their ongoing narratives and struggles against apologetics and anti-black racism.

For sake of application, one example of such a post-Orientalist post-apologetic approach would be to re-examine the Zanj Revolt, which is conventionally portrayed as a massive decade-long revolt of enslaved black peoples in the southern region of 9th century Iraq against the Abbasid Caliphate. The Zanj Revolt is one of the main examples cited in Orientalist debates about anti-black racism in the pre-modern Muslim world. Many Orientalists, such as the Zionist neo-conservative Bernard Lewis, overemphasize the existence of an exceptional plantation slavery system based in the marshes of Iraq – in order to draw comparisons to plantations in the Americas and to fight against the rising Afro-Arab internationalism of his time. Lewis also offers a false dichotomy of masses of “black people” uprising against their “Arab” rulers against said oppression; which begs the question, do black Arabs not exist? Arab has always technically been a term primarily denoting culture and language, not skin color, even though Arabs and non-Arabs have not always assumed this in practice. The anachronistic and ahistorical effort to project terms such as Arab and African back in time to analyze the question of anti-blackness in the Muslim world must be done with far more attention to detail and caution, least we want to play into anti-black and Islamophobic tropes that are far more ideological than historical.

In contrast to Lewis, historian of Islam M.A. Shaban long ago argued that the Zanj Revolt was one of the best-recorded events of the period, yet modern Orientalist scholarship has misconstrued its historical and sociological nature out of a Eurocentric bias. The Zanj revolt was part of wide-spread uprisings across the Levant and Persia against the authoritarianism and socio-economic exploitation of the Abbasid government. Shaban states that it should not be understood as a slave revolt, but as a more specific Zanj (Arabic for “black”) revolt, as the leadership and organizational structure of the revolt was led by non-enslaved blacks (of Arab and non-Arab descent), in collaboration with non-blacks, going as far as to say that a “Black-Arab alliance” was well-established in the leadership of the revolt, which lasted nearly 15 years. Gwyn Campbell’s more recent article “East Africa in the Early Indian Ocean World Slave Trade: The Zanj Revolt” also comes to similar conclusions, with the added help of decades of genetic research that has allowed scholars to determine with greater empirical accuracy the ebbs and flows of human trafficking in Africa and Asia during that time period. Citing the famed classical historian and Qur’anic exegete Muhammad ibn Jarir al-Tabari (d. 932 CE) – who was an eye-witness to the uprisings and directly quoted from the revolt’s leaders in his chronicles – Shaban and Campbell note that in addition to black people in southern Iraq, assumedly non-black Jews, Arabs, Persians and other exploited peoples in various regions of the Abbasid Caliphate’s jurisdiction were revolting as a wide-spread response to exploitation. This wider response contained within it the southern region of Iraq and its regional form of anti-black racism as part of the larger system of exploitation.

Readings such as Hamdan and Campbell challenge the anachronistic readings of Orientalists. Orientalists fail to contextualize and add complexity to the antagonisms raised above, such as overemphasizing plantation slavery for the sake of shifting blame, especially when that form of slavery was exceptional in the Muslim world. Rather, military, domestic and menial labour, and sex slavery were the more common forms, and they were used in even greater numerical capacity against non-black enslaved people from various regions inside and outside the relative boundaries of the Muslim world. Yet taking a stand against apologetics, Hamdan and Campbell do not downplay the fact that massive amounts of black people were in fact enslaved, and that their enslavement was based in part on racism.

In conclusion, those dealing with the Muslim world, Africa and their communities must critically engage indigenous languages and historical archives, and develop tools of social analysis based on a post-Orientalist and post-apologetic perspective.

“By engaging in a post-Orientalist and post-apologetic reading of events such as the Zanj Revolt – or more contemporary events such as the revival of slave trading in Libya, combatting anti-Sheedi racism in Pakistan, or movements to uplift and empower Afro-Iranians – we are able to more critically examine anti-blackness in various historical contexts without playing into Eurocentric, apologetic or ahistorical tropes.”

This article is not meant to be conclusive nor exhaustive, but is meant to provoke a more rigorous process for thinking through and confronting anti-blackness in the Muslim world. We must combine a more systematic and objective approach to the histories of anti-blackness in the Muslim world, alongside a more sensitive and subjective activist approach to confronting the ways anti-blackness is still very much alive. Much archival work needs to be done to understand antiblackness in terms of its materialist and cultural forms as a function and system of power in Islamic history, past and present. By engaging in a post-Orientalist and post-apologetic reading of events such as the Zanj Revolt – or more contemporary events such as the revival of slave trading in Libya, anti-Sheedi racism in Pakistan, or movements to uplift and empower Afro-Iranians – we are able to more critically examine anti-blackness in various historical contexts without playing into Eurocentric, apologetic or ahistorical tropes. Addressing and combating anti-blackness in the Muslim world must not perpetuate Orientalism, just as one would not want to address something like Islamophobia in Black Orientalism by in turn reinforcing anti-blackness. We must move beyond apolegetic roadblocks in the study of anti-black racism in the Muslim world so that we can deal with one of humanity’s most crucial ethical questions across time and place – have black lives mattered? And are we rigorous enough in our probing of this question to take history and its distortions seriously? Doing this type of work is not an abstract liberal scholarly denial of the current subjective and urgent struggle to dismantle and abolish anti-black racism in its various forms globally. Rather, we should view it as a task which furthers such a struggle and constructive debate in a way that does not lead to anti-black apologetics or Orientalism.

*Post-script note: I am particularly thankful to Dr. Nathaniel Matthews for his feedback and intellectual comradery in thinking through these issues.

Iskander Abbasi is a Palestinian-American PhD candidate at the University of Johannesburg. His work focuses in the fields of Islamic Liberation Theology, Decolonial Studies, Critical Muslim Studies, and Islam and Ecology. He is the Co-Convener of the Biennal Cape Town Critical Muslim Studies: Decolonial Struggles and Liberation Theologies Summer School, and a member of the steering committee of the Liberation Theologies group at the American Academy of Religion.