The Arthur M. Sackler Gallery’s dazzling new exhibition, “The Art of the Qur’an: Treasures from the Museum of Turkish and Islamic Arts,” offers Smithsonian museum visitors a new perspective on Islamic art. From the Sura 1: “Al-Fatiha” that greets visitors in the first room, projected on the wall in Arabic in an otherwise empty space, the exhibition privileges the confessional over the historical narrative. This is a surprisingly unusual approach to the presentation of Islamic art in Western museums, which usually organize such exhibitions within a formal, historical, geographic or archeological framework. As curator Massumeh Farhad explains in her excellent introduction to the catalogue, until recently the secular aspects, and not spiritual aspects, of Islamic art have been more evident in both the processes of collecting and displaying Islamic art outside of the Islamic world.

“…Until recently the secular aspects, and not spiritual aspects, of Islamic art have been more evident in both the processes of collecting and displaying Islamic art outside of the Islamic world.”This applies particularly to the study of Qur’ans as objects, the focus of this exhibition. She and other scholars attribute this tendency to privilege the secular aspects of Islamic art to a number of cultural factors, including a lack of familiarity with Arabic among Western collectors and librarians, and a Western preference for illustrated images over calligraphy.[1] One thinks of the Shahnama pages in the Sackler Gallery’s own Vever Collection of Persian and Indian manuscripts, assembled in Paris of the Belle Epoque by jeweler and connoisseur Henri Vever. Like other Western collectors, Vever was drawn to brilliant illustrations and decorative pages, with less interest in the content, calligraphy, or even the integrity of whole volumes.[2]

Exhibiting Calligraphy

As a student and teacher of Islamic art, but as a non-Muslim, I have my own perspective on these issues. Years ago, the Freer Gallery next door hosted an ambitious exhibition which addressed the problem of making Western museum-goers comfortable with looking at the art of calligraphy in languages they did not read. The exhibition, From Concept to Context: Approaches to Asian and Islamic Calligraphy displayed examples of Chinese, Japanese, Arabic and Persian calligraphy from the Freer’s collection and challenged the Western museum visitor, presumed ignorant of the languages, to engage with them as works of art. Using separate groupings of objects, the curators walked the viewer through differences between, say, Kufic and cursives styles of Arabic calligraphy while explaining the expressive content inherent in the different forms. To this day I treasure the lessons I learned in that show, and try to give my own students a bit of that same training in my Islamic Art classes, hoping that the ability to read a few basic names and phrases in different writing styles (“Allah,” “Muhammad,” and the Bismillah) might give my non-Muslim, non-Arabic-speaking students an entry point to the art by making the language less strange to them.

More recently the Sackler’s Dr. Farhad attempted something similar in “Nasta’liq: The Genius of Persian Calligraphy,” a small show presented in Fall 2014 through Spring 2015. While the beautiful calligraphy was clearly explained and thoughtfully presented, and complemented by educational and cultural presentations, the exhibition seemed to be attended almost exclusively by Persian speakers and the odd earnest student (my own included). By contrast, the spectacular illustrated pages in the Sackler’s recent Falnama and Shahnama exhibitions drew crowds.[3] Calligraphy is a hard sell, even to the self-selected audiences who find their way to the Smithsonian’s Freer and Sackler Galleries of Asian Art.

a small show presented in Fall 2014 through Spring 2015. While the beautiful calligraphy was clearly explained and thoughtfully presented, and complemented by educational and cultural presentations, the exhibition seemed to be attended almost exclusively by Persian speakers and the odd earnest student (my own included). By contrast, the spectacular illustrated pages in the Sackler’s recent Falnama and Shahnama exhibitions drew crowds.[3] Calligraphy is a hard sell, even to the self-selected audiences who find their way to the Smithsonian’s Freer and Sackler Galleries of Asian Art.

Exhibiting Islam

Of course, the other challenge for presenting a show like “The Art of the Qur’an” is an American audience’s unfamiliarity and even discomfort with Islam, especially in this year’s vicious political climate. In 2010 I was lucky enough to view the predecessor of this show in its home museum in Istanbul,[4] and the contrast is striking. There, the Qur’an and Islam needed no introduction and the exhibit was hugely popular. The material was presented historically as one would expect in, say, an exhibit of manuscript Bibles in any Western museum. The gorgeous gilded volumes glittered under low brick vaults with spotlights, naturally contextualized by their location in the ancient Ibrahim Pasha Palace and its proximity to the greatest mosques of the Ottoman period—well within auditory range of the Sultanahmet Mosque in fact, from whence the call to prayer occasionally penetrated the exhibition space.

The challenge in presenting core Islamic material in a respectful setting to an American audience at a Smithsonian museum is considerable.

“The challenge in presenting core Islamic material in a respectful setting to an American audience at a Smithsonian museum is considerable.”In my “Museum” course, we learn that the Smithsonian is taken to heart by most Americans as an essential piece of the national identity, and that exhibitions there frequently come under close Congressional scrutiny for any perceived transgressions of national sentiment, sometimes with drastic funding consequences. Hence my surprise at this national museum’s decision to put religion first, rather than placing the Qur’ans in the safer, more traditional framework of formal art-historical presentation.

The first gallery explains the Qur’an itself, its origins and its self-referential nature, using historic Qur’ans opened to relevant verses: the first revelation of Sura 96: Al-‘Alaq (The Clot), for instance, or the description of the Qur’an as a holy book that only the purified can touch, in al-Waqi’ah, Sura 56, verses 77-80. Throughout the exhibit the light levels are kept low and magnifying glasses provided, as is to be expected in an exhibition of manuscripts at the Sackler. The next room was the greater surprise for me. Around a large space, Qur’ans are opened to verses that explain core articles of Islamic belief (iman) and the nature of God, including Suras 112: Al-Tawhid (Unity) and 55: Al-Rahman (The Beneficent). A fourteenth century lamp from the Sultan Hasan mosque-madrasa complex in Cairo was brought over from the Freer to illustrate the Light verse from Sura 25: Al-Nur. Ancient Qur’ans in a range of formats and historical periods are used in the display, some from the Museum of Turkish and Islamic Arts loan, some from the Freer and Sacker, and a few from supplemental loans. But the emphasis is on the content of the Qur’an, not its form. Many of the selected passages are clearly aimed at a Western audience familiar with parallel stories and concepts from the Jewish and Christian scriptures, illustrating Islam’s understanding of the Jewish prophets, Mary, Jesus, and the Last Judgment. Other verses illustrate more specifically Islamic topics such as the nature of the Prophet, the umma, and the proper treatment of women, explained more fully through labels and wall texts.

Exhibiting the Arts of the Book

Only after this respectful and thoroughly satisfying introduction to Islam does the exhibition become formal and historical. A small space aimed at children’s education separates the two parts of the show. In a vitrine is displayed some writing materials such as gold leaf, lapis lazuli and treated papers, while a table and chairs are set out with pattern sheets for coloring. One would have liked a more serious treatment of materials and technique here, perhaps with videos such as the master calligrapher Mohamed Zakariya’s demonstration of calligraphy that was tucked into a more miscellaneous display room at the end.

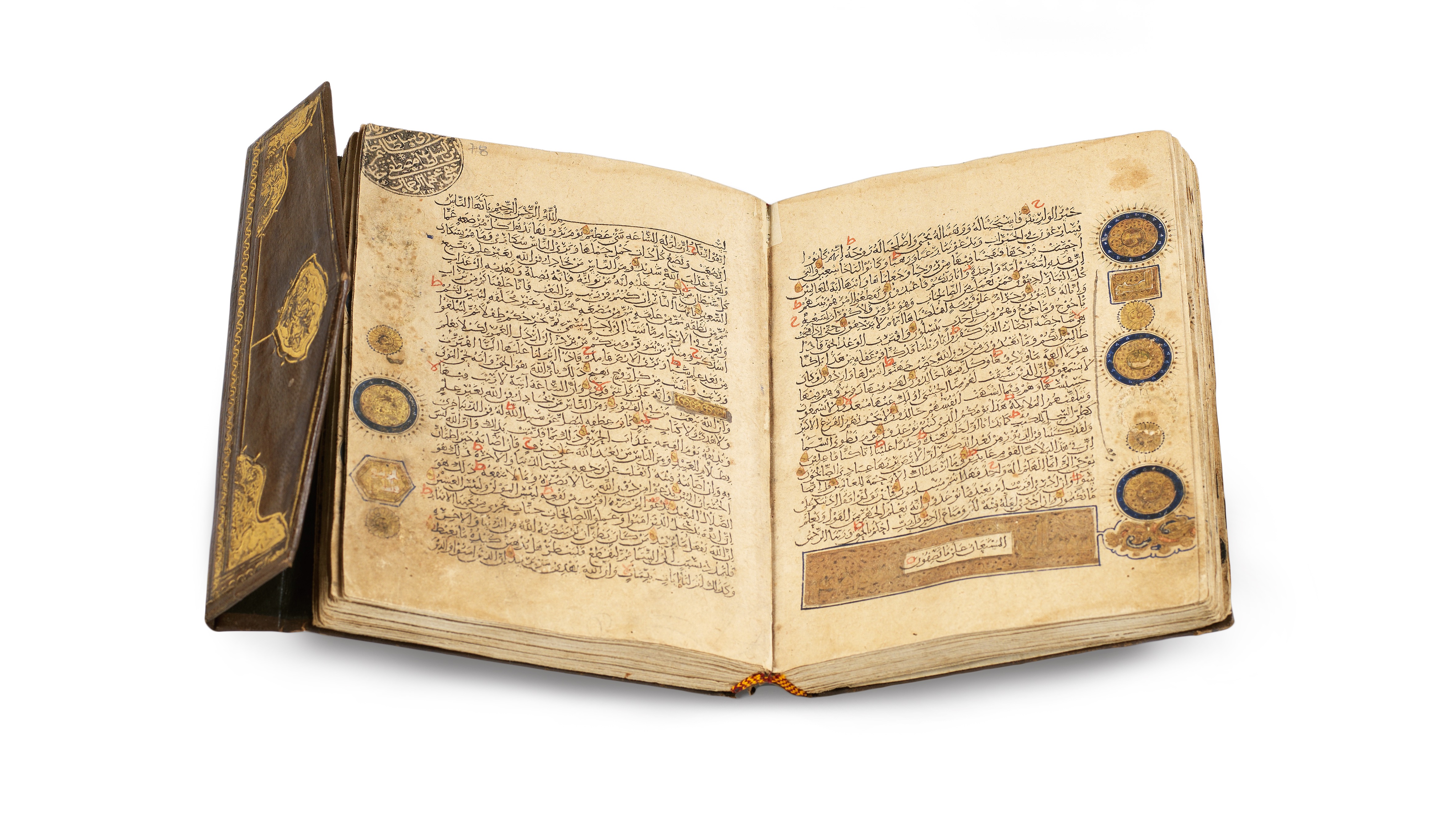

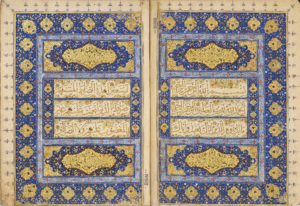

Most of the exhibition follows a magnificent historical survey divided into thematic sections. It is preceded by a pair of folios from an enormous Timurid Qur’an laid out as if opened on a reading stand, contextualized by a small black-and-white photo of its possible original stone stand in the Bibi Khanum Mosque in Samarkand. Only a few such contextualizing pictures are used in the show, and they seemed so very helpful that one wishes there were a few more. One thing I missed throughout the exhibition was a sense of the physical setting and use of these Qur’ans in the mosques themselves, before they were carted off to Ottoman tombs and libraries.

“One thing I missed throughout the exhibition was a sense of the physical setting and use of these Qur’ans in the mosques themselves, before they were carted off to Ottoman tombs and libraries.”Given the close connection between the art of the Qur’an and the art of reciting it orally—divisions, breathing marks and so on, as explained in the labels and throughout the catalogue—I would love to have seen and heard a video centrally placed in this section, showing how a manuscript Qur’an would guide a reciter. It would have added much to our holistic understanding of the art of these Qur’ans in their original cultural contexts.

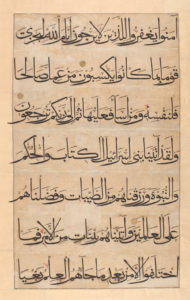

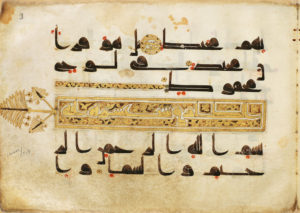

With that one reservation, I found the thematic galleries very rewarding. The first two, “Chapter and Verse” and “Ink and Gold,” explain the paired evolution of both the Qur’an and written Arabic in clear terms, illustrated with spectacular examples beginning with rare and spare seventh-century Hijazi pages and gilded Abbasid Kufic parchment pages from luxury 30-juz sets. Later paper editions from the tenth century on, some written in Eastern Kufic, or “new style” calligraphy, lead into an impressive display of examples penned by famous calligraphers, the labels explaining just enough about each calligrapher’s talents and idiosyncrasies to engage even lay visitors. I found particularly interesting the examples of false attributions, to the fourth Caliph Ali ibn Abi Talib for instance, or to Ibn Tawwab. In an odd way, they bring home for the viewer the status and culture of calligraphy as seen through calligraphers’ and collectors’ eyes.

With that one reservation, I found the thematic galleries very rewarding. The first two, “Chapter and Verse” and “Ink and Gold,” explain the paired evolution of both the Qur’an and written Arabic in clear terms, illustrated with spectacular examples beginning with rare and spare seventh-century Hijazi pages and gilded Abbasid Kufic parchment pages from luxury 30-juz sets. Later paper editions from the tenth century on, some written in Eastern Kufic, or “new style” calligraphy, lead into an impressive display of examples penned by famous calligraphers, the labels explaining just enough about each calligrapher’s talents and idiosyncrasies to engage even lay visitors. I found particularly interesting the examples of false attributions, to the fourth Caliph Ali ibn Abi Talib for instance, or to Ibn Tawwab. In an odd way, they bring home for the viewer the status and culture of calligraphy as seen through calligraphers’ and collectors’ eyes.

The Ottoman Imperial Collectors

The final part of the exhibition focuses on the Ottoman patrons and collectors themselves, featuring some of the most spectacular pieces in the show, grand and gilded as befitted their status as imperial gifts, commissions, and tomb treasures. Wall texts explain their use as objects of power and display, with baraka deriving from their place of origin –the Prophet’s Mosque in Medina, for example, or Jalal al-Din Rumi’s tomb in Konya. Several objects, such as Qur’an cabinets and fragments of inscribed textiles from the Ka’aba’s kiswa,[5] add rich visual variety as well as context for the books themselves. Old prints and photos help tell the story of these books’ use in Ottoman imperial tombs and libraries. Again, one wishes the show had done the same earlier to explain how the Qur’an (physical and auditory) was used in mosque settings. A particularly interesting and unusual part of this display dealt with Ottoman imperial women’s patronage, with examples of Qur’ans commissioned and dedicated as waqf for their own or their husband’s tombs. This is a story I did not know, and it complements the better-known story of imperial women as patronesses of architecture.

Supporting Materials

A final room builds on the exhibition with a miscellany of technical videos, archival photos, and catalogue information presented through multimedia. One is delighted to find our nationally-famous local calligrapher Mohamed Zakariya featured in a film demonstration of naskh and thuluth calligraphic technique—a film I would have found more effective in the space with educational materials, to be viewed before descending to view the actual examples. Photos and maps of the Turkish and Islamic Arts Museum itself begin to tell its history, but I would like to have seen this given more emphasis. How and why these Qur’ans came to be collected from Ottoman mosques, tombs and libraries and deposited there between 1914 and 1922 is itself a fascinating coda to the history of the Qur’an. Only in the catalogue do we learn that the museum was founded by the Grand Vizier Huseyin Hilmi Pasha’s orders in response to vandalism, neglect and theft resulting in Turkey’s treasures being stolen and sold to foreign collectors during the Empire’s most troubled years.[6] Even before Mustafa Kemal Atatürk’s secular Turkish Republic, these Qur’ans had been transformed from objects in devotional use to objets d’art. But then again, as I learned from the exhibit, they had been collected as such for centuries by Islamic rulers, connoisseurs of the art of the book.

The catalogue is the most useful byproduct of the show, of course, with excellent essays by the curator and leading scholars that I will find useful in future teaching. A final delight in the catalogue was seeing the name of our former George Mason University student Sana Mirza, a curatorial assistant at the Sackler, listed as a contributor on the title page. This teacher is very proud.

An Appreciation

So how will this show be received by non-Muslims? I would like to think that given Islam’s topical importance in American discourse, simple curiosity might overcome any reluctance to engage. Perhaps the display of the Islamic in its own spiritual terms will become as accepted in American exhibitions as, say, Buddhist devotional art has been. Whether that is true remains to be seen, and I am sure the Sackler is watching attendance carefully. The exhibit itself appears to be watched by an unusual number of guards, and rumor has it that negotiations for the show with Turkey were fraught with concerns over politics and security.

The museum and its staff are to be commended first of all simply for pulling it off. More, they are to be commended for putting the spiritual aspect of the Qur’an first, confronting any ignorance or prejudice about Islam head-on, using the medium of these historic Qur’ans as teaching tools about the faith before presenting them as art. And finally, wearing my art-historian’s hat, I commend the Sackler for a breathtakingly beautiful show of important new material for American audiences that engages the scholar, the student, the committed Muslim, and the lay visitor equally.

*The top three images are provided courtesy of the Sackler Gallery. We also thank Rami Skooti for his permission to use his photo from the exhibit.

[1] Massumeh Farhad, “Introduction,” in Massumeh Farhad and Simon Rettig, The Art of the Qur’an: Treasures from the Museum of Turkish and Islamic Arts (Washington: Arthur M. Sackler Gallery, 2016), 20-21.

[2] Glenn D. Lowry and Susan Nemazee, A Jeweler’s Eye: Islamic Arts of the Book from the Vever Collection ( Arthur M. Sackler Gallery, 1988), 34-35.

[3] “Falnama: The Book of Omens,” on display 2009-10; “Shahnama: 1000 Years of the Book of Kings,” on display 2010-2011.

[4] “The 1400th Anniversary of the Qur’an” at the Museum of Turkish and Islamic Arts, Istanbul, opened 2010.

[5] The cloth that covers the Ka’aba.

[6] The Art of the Qur’an: Treasures from the Museum of Turkish and Islamic Arts, foreword by Seracettin Şahin, 9.