Introduction

This paper aims to provide an overview of the historical and contemporary developments of the Xidaotang 西道堂 (lit. “Western Path Hall” or “Western Daotang [1]”), a Chinese Muslim community. First, I will examine the reasons why Xidaotang has not, until today, been officially recognized as a Sufi order. Second, I will interrogate why the expression “Han Studies School (Hanxuepai 汉学派),” which was coined by Islamicists during the 1980s, has been used to describe this Islamic movement. Third, based on a more economic perspective, I investigate why the Xidaotang thrived in Amdo during the Republican period. Finally, I explore the processes whereby Xidaotang has today become an object of specific treatment by the local authorities.

Xidaotang and “Islamic teaching schools” with Sufi origins

To this day, scholars lack sufficient historical evidence to describe Islamic practices during the Imperial period in a comprehensive manner. We do know that Chinese Muslims oriented themselves toward orthodox Sunni practice belonging to the Hanafi school of law in late-imperial times.[2] In the wake of the Communist takeover in 1949, the CCP, inspired by Stalinist ideology, decided to turn China into a multi-ethnic state in 1953. As a result, 56 nationalities were identified, of which 10 are Muslim. Among them, the Hui people correspond to the contemporary ethnic category encapsulating Muslims who express their religious identity using the Chinese language as their main medium. Xidaotang’s members belong to this ethnic category.

“In the wake of the Communist takeover in 1949, the CCP, inspired by Stalinist ideology, decided to turn China into a multi-ethnic state in 1953. As a result, 56 nationalities were identified, of which 10 are Muslim. Among them, the Hui people correspond to the contemporary ethnic category encapsulating Muslims who express their religious identity using the Chinese language as their main medium. Xidaotang’s members belong to this ethnic category.”

Today’s official taxonomies of Chinese Islam, which have been adopted by the Party-State, draw on the pioneering work of Ma Tong regarding Chinese Islam.[3] Ma Tong, born in 1929, served as a party-member and a government official since 1949. During the 1950s, his personal interest in the state of Islam in Northwestern China drove him to study Islamic teaching schools and Sufi orders of that region, which were virtually unstudied up until his time. In the 1980s, thanks to his work, Chinese Islam was for the first time studied and presented to the public in a comprehensive fashion. In his studies, he describes, “the three great teaching schools (the Gedimu, Yihewani, and Xidaotang schools)” and “the four great Sufi orders (the Qadiriyya and Kubrawiyya orders, and two orders of the Naqshbandiyya, namely Khufiyya and Jahriyya).” These four great Sufi orders are themselves sub-divided into more than forty sub-branches.

In Chinese, following Ma Tong’s categorization, the term which refers to “teaching schools” is jiaopai 教派 and that which refers to “Sufi orders” is menhuan 门宦.[4] During the imperial period, these two Chinese terms were not emic categories, since they are only used by Chinese officials when describing Chinese Muslims’ religious organization. At that time, Muslims did not quite identify with these terms.

What is striking in Ma Tong’s typology is that Xidaotang is not considered as a menhuan. The political context of the 1950s and the personal relation between Ma Tong and Xidaotang’s religious elite ought to be considered to fully comprehend the categorization applied to Xidaotang, but before doing so, it is worth reviewing the genesis and the history of Xidaotang to establish the religious backdrop in which the movement arose.

Xidaotang’s religious characteristics

Ma Qixi, the founder of Xidaotang, born in 1857, was brought up in a family that already played a crucial role in the development of Sufism in Lintan. His mother was one of the daughters of the shaykh of the Beizhuang order, a sub-branch of the Khufiyya, and his father served as the imam of the Beizhuang Mosque in Lintan.

His father, realizing the potential of his precocious son, decided to send Ma Qixi to a Confucian private school, where he received a Chinese classical education while continuing his education in Islam at home. After achieving the civil rank of xiucai (a scholar who passed the imperial examination at the county level), while renouncing to go further in the higher rank of juren at the provincial level, Ma Qixi drew on his dual education to open his own secular school named Jinxing tang 金星堂 (the Gold Star Hall) in 1890. Then in 1901, on account of a quarrel regarding funeral rituals, he resolved to sever his links with his original menhuan. This decision triggered unprecedented conflicts between Ma Qixi’s newly created order and his former menhuan. After an escalation of violence, Ma Qixi decided to go on a pilgrimage to Mecca, but was forced to stay in Samarkand for two years because of ongoing turmoil in Russia. When he returned from this spiritual journey in Central Asia, which Chinese Muslims deemed a holy place, he decided to name the new spiritual path he had created “Xidaotang.” Some Xidaotang hagiographic sources assume that the center of reference for giving Xidaotang its name is the Ma Yuanzhang’s Jahriyya order in Zhangjiachuan, situated at the East of Lintan., meaning that the daotang of Ma Qixi is on the western side of Ma Yuanzhang’s daotang, i.e. “Western daotang.”

Although Ma Qixi founded his path in an autonomous way, he was always in admiration of the success of Ma Mingxin’s thought for he made the rebirth of Jahriyya possible and developed its religious doctrine. By then, as he set out on long journey to the West, what he saw and heard along the road sparked deep emotions in him. Upon his return home, he changed the name “Jinxing tang” into “Xidaotang,” and showed his determination by proclaiming: “Jielian planted the seeds, Guan Chuan made the flowers bloom, I want to reap the fruits.” At the time, Ma Qixi used to discuss religion with Ma Yuanzhang in Zhangjiachuan, in the village of Xuanhuagang. And they were profitable discussions. Thus, relying on his noble ambition and strong will, he adopted the spirit of “Guan Chuan” to establish the religious tenets he wanted to propagate.

When studying Xidaotang, one of the most important features to keep in mind is that, contrary to other Sufi Orders (Qadiriyya, Kubrawiyya, Naqshbandiyya), Xidaotang originated very late – at the end of the nineteenth century. Moreover, the order was not imported by missionaries from Central Asia or the Middle East, who started their proselyte work in Northwest China in the second half of the seventeenth century. Chinese Islamicists thus consider Xidaotang to be a genuine product of Islam in China, that is to say the first manifestation of a rooted Chinese Islam.

“When studying Xidaotang, one of the most important features to keep in mind is that, contrary to other Sufi Orders (Qadiriyya, Kubrawiyya, Naqshbandiyya), Xidaotang originated very late – at the end of the nineteenth century.”

From a liturgical point of view, Xidaotang shared the same basic texts with other Sufi orders:

- maoluti 卯路提, introduced in China by Ma Laichi, founder of the Khufiyya Sufi order. Sacred text used to celebrate the life of the Prophet.

- madīha (madā’ih) (mai-da-yi-hai 买达依亥), introduced in China by Ma Mingxin, founder of the Jahriyya Sufi Order. Liturgical text used to praise the glorious accomplishments of the Prophet.

- Mukhammas (mu-han-mo-si 穆罕默斯), also called bailati 白拉提 (ode or poem). Ode praising the Prophet. Introduced by the Jahriyya.

In the same way as other tariqa, the goal of the path in Xidaotang is to move closer to God and to reach the “ḥaqīqat” (Complete Path or Vehicle of the Truth) by following the “three paths” or “three vehicles.” The first level of the path – the observance of the Sharia – is how Islamic law is understood by Xidaotang believers.

The three levels of proximity to God [5]

From a ritual point of view, the oral field survey I conducted shows that the dhikr–remembrance of God’s name – is no longer practiced today in public, even though it is still sometimes practiced within families. From a spiritual point of view, due to the secession from its original Sufi lineage, Xidaotang seems to lack a silsila, thechain of spiritual descent, in contrast to some other Sufi orders in China. Xidaotang’s religious leadership is not actually concerned with an imagined holy genealogy that would link the shaykh to the Prophet Muhammad. Nevertheless, they emphasize the intellectual genealogy that links Ma Qixi to Liu Zhi (ca. 1662-1736, dates are controversial), a renowned Muslim Neo-Confucian scholar. One of the reasons for this unique perspective on spiritual lineage might be that the transmission of charismatic power inside this Islamic order is based on merit (like in the Jahriyya before it). As a result, Xidaotang’s five generations of saints were not chosen using a hereditary criterion. In any case, the cult of the saints has endured even if their graves lack any built structure, contrary to other Sufi mausoleums.

However, the reasons why Ma Tong classified Xidaotang as a teaching school rather than a Sufi order were more ideological than scientific. Considering Xidaotang as a modern and reformist movement, Ma Tong, who had lived in a Xidaotang compound in Lintan for two years in 1951-1952, skillfully devised a way to extract Xidaotang from the menhuan category, thus minimizing its Sufi characteristics. From the Land Reform (law on June 30, 1950) onward, government political officials considered the menhuanas feudal and backward. In the wake of the Opening Policy initiated in the 1980s, one way to legitimate the separation of Xidaotang from Sufi orders was to label it the “Han Studies School (Hanxuepai)”.

A new and controversial label: the “Han Studies School (Hanxuepai)”

In the 1980s, the phrase “Han Studies School” became a standard label used by Chinese Islamicist literature to reference Xidaotang. The roots of this label may be traced to Ma Qixi’s use of what we today call “Han kitab,” i.e. a corpus of Islamic literature written in Chinese. Recent scholarship has established that the reading of Han kitab in religious circles was widespread in Northwest China at the end of the nineteenth century. Ma Qixi was a pioneer in integrating this literature written in Chinese into his curriculum on Islamic knowledge. He would have been further motivated by the fact that the majority of Chinese Muslims were illiterate in Arabic and Persian. Overall, he wanted to make Islamic knowledge, even if written in Chinese, accessible to everyone. Branded as condoning a heretical practice by the most conservative Muslim groups, Ma Qixi faced harsh criticism and even violence. This new way of teaching attracted numerous Muslims from other orders, and also Han Chinese – that is to say non-Muslims – who belonged to influential local lineages.

“Ma Qixi was a pioneer in integrating this literature written in Chinese into his curriculum on Islamic knowledge. He would have been further motivated by the fact that the majority of Chinese Muslims were illiterate in Arabic and Persian. Overall, he wanted to make Islamic knowledge, even if written in Chinese, accessible to everyone.”

As early as the start of the twentieth century, Ma Qixi, as both a Confucian and a Muslim scholar, was committed to implementing a rigorous policy of education in his community. Evidence of this engagement is that his daughters were highly educated women. Following his footsteps, Ma Mingren, the third shaykh of Xidaotang, created schools in Lintan which blended secular and religious education and were open to Muslim and non-Muslim boys alike. From the 1930s onward, Xidaotang started to welcome intellectuals in its midst, scholars who had studied in renowned universities. In 1943, the first female school, Qixi nüxiao, was opened, where young girls received a modern and secular education. The development of this modern education can be largely accounted for by the general economic expansion of Xidaotang.

Xidaotang economic development during the Republican period

The literature investigating Xidaotang usually focuses on its economic activities in Amdo during the Republican period. Indeed, the 1930s-1940s can be considered Xidaotang’s “Golden age.” In an unedited document, Robert Ekvall, a missionary and anthropologist, described Xidaotang’s compound as a “well-run society” when he referred to its collective socio-economic structure.

He [Ma Qixi] was also a communist in the primitive untainted-by-Marx sense of the word and the sect was organized accordingly. Upon acceptance the convert turned in all his wealth and then found a level of work and activity according to his skills and capabilities, and received a living that matched that level […]

With an ample agricultural base and numerous artisans and craftsmen to give it a high level of autarchy the sect ventured widely in trade, that extended its interests from Central Tibet to the Eastern seaboard with phenomenal success. The men at the top, with a strangely successful disinterestedness—no one could accumulate a private stake—made plans with daring and foresight. Furthermore, and most surprisingly, from the scores of members whom I had known over the years I had never heard any complaints about the distribution of benefits throughout all levels of the organization.

“A well-run society” I explained to Eva as we reached the big gate of the Tao-chow New Sect compound. […]

As a matter of fact, some faithful used to live collectively inside ‘large compounds,’ while others chose their dwelling outside this collective structure. The economic organization of this community was grounded in five sectors: agriculture, forestry, livestock farming, manufacturing (such as plant oil mills, sewing workshops, saddlery), and trade (such as long-distance caravan trade and commercial establishments). Relying on these diversified resources, the community gained autonomy and was able to thrive in a near self-sufficient manner.

Its trading company, under the corporate name of Tian Xing Long, became an important stakeholder in the brokering, transporting, and selling of many types of goods. Xidaotang’s trading network in the Tibetan regions was shaped both by long-distance caravan trade and retail shops located at trading posts.[6]

“After the communist takeover, the late 1951-1952 Land Reform in Lintan was not implemented inside Xidaotang. At that time, Ma Tong was sent from Linxia to Lintan to serve as a negotiator between the Xidaotang leadership and the Communist party.”

After the communist takeover, the late 1951-1952 Land Reform in Lintan was not implemented inside Xidaotang. At that time, Ma Tong was sent from Linxia to Lintan to serve as a negotiator between the Xidaotang leadership and the Communist party. Their negotiations led to Xidaotang’s supplying resources in kind as their contribution to the Land Reform. In 1958, all community members were expelled from the compound for good, and were forced to integrate into the production teams of the People’s communes, namely the largest collective units in rural area. A significant percentage of the male members, branded as “historical counterrevolutionaries,” were either imprisoned or sent into forced labor camps. At the beginning of the 1980s, after Deng Xiaoping’s political and economic reforms, Xidaotang members were politically rehabilitated. The tombs of the saints, desecrated during the Cultural Revolution, were replaced and their bones were buried anew in February 1979.

Xidaotang: a model of adaptability of Islam to socialism?

From the 1980s onward, the Xidaotang community has been experiencing an economic revival thanks to the capacity of the daotang to create a collective company named Tian Xing Long (reviving its past name) and thanks to current Shaykh Min Shengguang’s acumen. These trade companies, owned by daotang, havespecialized in trading silk and satin fabrics, and have reaped profits such that they have been able to rebuild places of worship for the community and to promote schooling. From the beginning of the 1990s until the middle of the 2000s, many young merchants benefited from this economic opportunity to earn a living and to learn a trade. Then, during a transition period, the collective companies were progressively closed down and personal businesses based on individual profiting replaced them. Thus, the daotang economy switched to real estate.

From a political point of view, Min Shengguang started a political ascent as early as the 1980s, first at a local level in Lintan, as a representative to the CCPPC, and today as a representative to the provincial level of the same political body. He also serves as an expert of religious issues in different ad hoc commissions. In 1994, he was elected as an exemplary figure by the State council for his contribution to the inter-ethnic dialogue and for promoting educative projects.

Today, this economic development and this political representation enable Xidaotang to expand in Lintan and beyond. Xidaotang is increasingly asserting its Sufi identity while also emphasizing its loyalty to the Chinese government by affirming its belonging to Chinese culture.

Conclusion

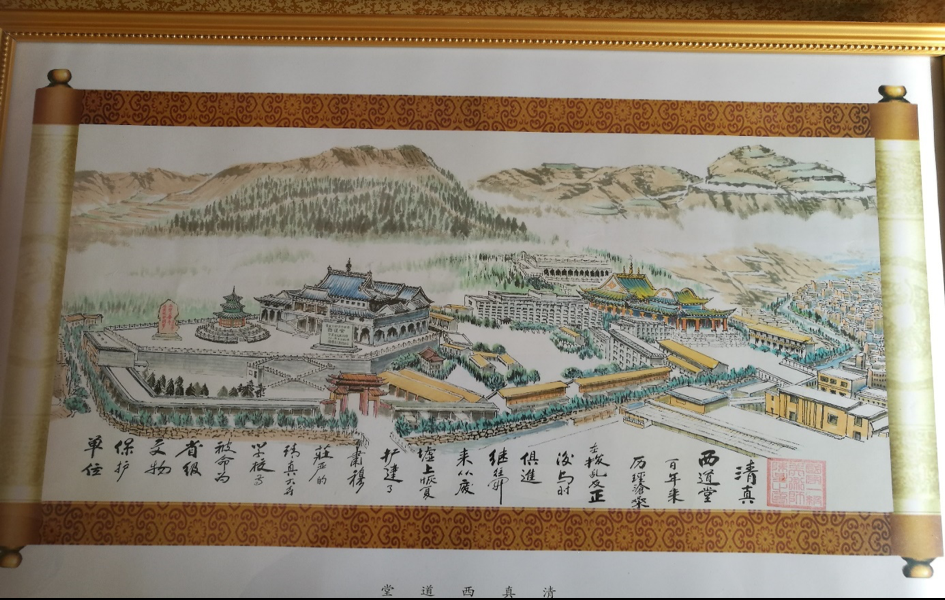

In 2014, for the 100th anniversary of the death of its founding saint, Xidaotang engaged in a double process of “sanctuarization” and “patrimonialization” of its religious place in Lintan. To a certain extent, Xidaotang matches the government’s and Party’s new policies toward religion in China by displaying a traditional Chinese style in the architecture of religious places (as in the past). At the same time, however, the community reaffirms a core element of its identity, namely the pilgrimage activities around the tombs of the saints and its capacity to foster unity according to the umma spirit.

Marie-Paule Hille (Associate Professor, EHESS, Paris) is an anthropologist and historian. Her research interests cover different aspect of the history of Muslim communities in northwest China. Her recent publications touch on political and economic aspects of Tibetan-Muslim relations in Amdo (co-edited volume, Muslims in Amdo Tibetan Society: Multidisciplinary Approaches, Lanham (Md), Lexington Books). She also has been researching religious practices related to the cult of the Muslim saints in the Tibetan areas of Western China since 2005 (last publication on that topic: « Le Maître spirituel au sein du Xidaotang. Enquête sur la reconnaissance d’une autorité sainte en islam soufi chinois (Gansu) », Archives de sciences sociales des religions 173, 2016).

[1] In Chinese Islam “daotang” generally refers to a place of Sufi meditation in its restrictive meaning, or, in a broader sense, any sacred site. For a definition see Wang Ping, “‘Ziyara’ and the Hui Sufi Orders of the Silk Road,” in Sugawara Jun, Dawut Rahile (eds), Mazar. Studies on Islamic Sacred Sites in Central Eurasia, (Tokyo: Tokyo University of Foreign Studies Press, 2016), p. 50-51.

[2] About Islamic legal thought in China during the imperial period see Roberta Tontini, Muslim Sanzijing. Shifts and Continuities in the Definition of Islam in China, (Leiden: Brill, 2016).

[3] Ma Tong马通, Zhongguo yisilanjiao jiaopai yu menhuan zhidu shilüe 中国伊斯兰教教派与门宦制度史略 [The History of China’s Islamic Teaching and menhuan system], Lanzhou, Xibei minzu xueyuan yanjiusuo, 1981.

[4] Wang Ping states that « The term menhuan (门宦; Sufi order) first appeared in March of the 23rd year of the Guangxu Emperor in a document submitted to the throne entitled Chengqing Caigu Huijiao Menhuan (呈请裁革回教门宦) [Beseeching the Removal of the Muslim Menhuan] by Yang Zengxin (杨增新), the governor of Hezhou ». Wang Ping, op.cit., p. 49.

[5] Table reproduced from Françoise Aubin, « En Islam chinois : quels Naqshbandi ? », in Gaborieau Marc, Popovic Alexandre, Zarcone Thierry (eds.), Naqshbandis. Cheminements et situation actuelle d’un ordre mystique musulman. Istanbul/Paris, Isis, 1990, p. 491-572.

[6] On this topic see “Rethinking Muslim-Tibetan Trade Relations in Amdo: A Case Study of the Xidaotang Merchants.” In Muslims in Amdo Tibetan Society. Multi-disciplinary Approaches,edited by Marie-Paule Hille, Bianca Horlemann, and Paul K. Nietupski, p. 179-206. Lanham, MD: Lexington Books.