“My family were persecuted by Gamal Abdel Nasser” says Khaled Abou El Fadl, an American lawyer, Muslim jurist and Professor of Islamic law at UCLA. “So, growing up, I saw first-hand the impact of political persecution,” he continues, “and that had a deep impact on me, as I saw and experienced the way governments with un-fettered and unrestrained power work, and the injustice that usually follows.”

His family would have to leave Egypt, bouncing between Jordan, Lebanon and Kuwait, and even becoming stateless at one point, which created an anxiety that he still recalls today. But his friends wouldn’t be so fortunate, “many disappeared,” he says.

Professor Abou El Fadl pursued his studies in the US after leaving the Middle East, where who would study at Yale and the University of Pennsylvania, before completing a doctorate in Islamic Studies at Princeton in 1999. He would go onto publish prolifically in the fields of Islamic studies and law. Some of his most prominent works include Reasoning with God, a deeply personal account of his disappointment that “Muslims have been struck by a colonially induced amnesia toward their collective memory.” He proposes a more deeply grounded ethical perspective, focused on goodness and beauty to reclaim and reassert Islam’s core message in the modern world.

Another important work was And God Knows the Soldiers: The Authoritative and Authoritarian in Islamic Discourses, where Abou El Fadl critiqued the authoritarian trend in some contemporary Islamic discourses. Here, he outlined his objection to the zeal with which some Islamic movements, declaring themselves protectors and carriers of Islam, degrade women, curb critical thought and neutralize the moral foundations of Islamic law.

To that end, in 2017, he took part in founding the Usuli Institute, an Islamic think tank, focused on “building upon the foundations of the rich and nuanced Islamic jurisprudential tradition” to “apply God’s timeless moral imperatives to our current world.”

Professor Abou El Fadl spoke to me about the impact of Crown Prince Mohammed bin Salman’s reforms and how these impact the landscape of Islamic scholars and scholarship in Saudi Arabia. While the Crown Prince has recently come under fire for domestic and foreign policy decisions which have embarrassed many of his supporters, a lot less attention has been paid to the religious impact of his reforms as their social import has confronted Saudi clerics with the stark choice between changing their views to accommodate the young Crown Prince or face potential imprisonment or worst.

Faisal Ali: Can you give us an idea of how the reform program of the Crown Prince has impacted the religious opinions and the views of clerics in Saudi Arabia? Where were they before and where are they now?

Khaled Abou El Fadl: Well, it is a pretty complicated question because under the existence of coercion and political oppression it is really difficult to tell what a lot of Saudi scholars actually believe. But, what has been coming out of some Saudi scholars and the Saudi Permanent Council of Senior Scholars is a reversal on a wide variety of issues. The most obvious one is the example of Abdelaziz Al-Shaykh who once described women driving as “the worst kind of evil,” and now says there is no problem with it. The issue here is that he does not even address his previous fatwa (ruling). The same, of course, goes for music and singing.

But one of the most interesting developments is the acceptance of holidays which are not a part of the early Islamic tradition. This is an issue that Saudi scholars have written polemically about and have created a sizeable discourse on, forbidding Muslims from celebrating any holidays which are not Islamic which they view as bidah (innovations in matters of faith). Not only were celebrations like Valentine’s Day condemned, but others like Labor Day, birthdays and of course most controversially the birthday of the Prophet Muhammad were also outlawed.

“Muftis or scholars are expected in the Islamic tradition to address previous legal rulings, especially when they come from the same genealogy of thought. You come from a line of jurists or a tradition and there are problems when an individual just breaks ranks, or ignores his own prior rulings and follows the dictates of political figures. This is partly why scholars like Salman al-Oudah, Salih al-Fawzan, Safar al-Hawali, and Awad al-Qarni have all been arrested and thrown in prison.”

Muftis or scholars are expected in the Islamic tradition to address previous legal rulings, especially when they come from the same genealogy of thought. You come from a line of jurists or a tradition and there are problems when an individual just breaks ranks, or ignores his own prior rulings and follows the dictates of political figures. This is partly why scholars like Salman al-Oudah, Salih al-Fawzan, Safar al-Hawali, and Awad al-Qarni have all been arrested and thrown in prison. These are scholars who are of the same tradition, the same process of authentication and line of thinking, but they are treated differently because they did not toe the line.

Contrast that with others like Mohammad al-Arefe, Aid al-Qarni, Abdul-Aziz ibn Abdullah Aal Al-Sheikh who are all basically stamping whatever they believe the current authority wants. Sometimes very explicitly and sometimes very implicitly.

If I may play the devil’s advocate for a minute here some may argue that this is a credit to Mohammed bin Salman whose uncompromising approach has put the clerics on notice. He has forced them to modify their views. How would you respond to such a claim?

This stems from orientalist tropes, which were constructed by orientalists who believed that only despotism works in Muslim societies. Muslim societies, they said, are anchored in despotic rule, they need it to grow and they only understand despotism. But even if we go with the myth of the just or enlightened despot, many of these “great reformers” inflict a great amount of violence and trauma on their societies. Yes, there were liberties, or some limited openings, but the long-term consequence was the destruction of the very fabric of society. Historians look at episodes such as the one that took place in Germany and that society’s great reformer, Frederick the Great, for example. They make an important point in linking his reforms to the eventual collapse of democracy and the emergence of Nazism and Fascism in Germany.

“This stems from orientalist tropes, which were constructed by orientalists who believed that only despotism works in Muslim societies. Muslim societies, they said, are anchored in despotic rule, they need it to grow and they only understand despotism.”

Now if you look at these societies which have been colonized, where we have had rulers who believed that despotism was the only way forward, what we see is extreme polarization, between the reforming despot and his associates and the counter-reaction to that despot which creates cleavages in societies between irreconcilable ends. This sometimes leads to the kinds of horrendous bloodshed that we are seeing today in Syria, the rise of ISIS, Iraq previously, and so on…. And in other places, societies become rigid and frozen for fear of allowing opposition members space. The people creating the polarization, and those who have encouraged such despotism traditionally, such as Daniel Pipes, Thomas Friedman, Bernard Lewis and so on, have no regard at all for the lives of Muslim people.

How have these developments impacted the relationship between the general public in Saudi Arabia and the scholarly class?

The generation of the post-Arab Spring is characterized by a loss of confidence in the voice of the representatives of the Islamic tradition. If you look at what is happening in Saudi Arabia, the Emirates or Egypt there is a growing skepticism about religiosity and religious discourse in a way that is disconcerting to me. It is not a movement of Islamic enlightenment that is winning the hearts and minds of people, but rather a political maneuvering that is causing people to lose confidence and trust in the Islamic tradition. And that’s made worst by episodes like Mohammed bin Salman climbing atop the Kabah and inspecting it like it is a private piece of work alongside the silence of the scholars on this issue. This dovetails with the explosion of Islamophobia not just in the West, but also in our Muslim countries.

What are the moral implications of this issue you identify with some scholars in Saudi Arabia?

I am seeing some very damaging trends that, among other things, are leading to an abdication of some very important responsibilities for scholars. Scholars closely affiliated with governments and those who are state functionaries are not a new development in Muslim countries. But to hear major Saudi scholars coming out and saying things to the effect of “even if the King fornicates on TV for half an hour every day, not only should you not criticize him but you also should not think ill of him” is absolutely shocking. They are pretending that the important parts of the Islamic tradition, which encourage believers to hold rulers to account do not exist.

“I do not believe the consequence of this total cooptation of Islamic scholars by Mohammed bin Salman will mean that people believe what these scholars say. But people are increasingly rebelling against Islam itself. “

I do not believe the consequence of this total cooptation of Islamic scholars by Mohammed bin Salman will mean that people believe what these scholars say. But people are increasingly rebelling against Islam itself. Young people are increasingly persuaded that Islam is a religion which basically advocates blind obedience to oppression and injustice. There was even a scholar who said if the ruler chooses to kill a third of the population, you do not have a right to oppose him. What they are basically saying is that even if a ruler commits genocide, Islam demands you to remain obedient, which is absurd. For young Saudi people who I often encounter, I am struck by the extent of their rebellion against religion because of issues like this.

For thirty years people like me have been banned, marginalized, black listed, excluded because we were always accused of being Westernized, or being people who want to imitate the West and so on. After all these years of this vitriol, they make this immediate u-turn without the smallest acknowledgement that through their rulings they have destroyed so many lives. I have worked in human rights for years, and I cannot tell you how many people I know of who were flogged or imprisoned for things like driving. The net effect of this is the de-legitimization of Islamic legal thought, and its processes as well as its representatives.

I grew up in despotic countries and Abdulrahman al-Kawakibi has a fantastic book he wrote about the impact of despotic rule on people titled The Nature of Despotism, and one of the most serious consequences of despotism he said was that it creates a culture of hypocrisy. And these dynamics make words lose their value because you can no longer reliably trust anything anyone says. Many of these scholars held their opinions with such zeal that they believed there could be no second opinion, and suddenly overnight the meaning of words like haram (forbidden), bidah (innovation) and so completely changed. It should come as no surprise then that people begin to doubt.

The situation today reminds me of Egyptian society after the invasion of Napoleon in many ways. Many scholars of al-Azhar University celebrated Napoleon as a convert to Islam despite his violence. Egyptian society then became full of a genre of poetry which mocked religion. In Egypt, we are still living with the consequences of that invasion. The important question is then whether we also have to live with the consequences of Mohammed bin Salman’s time in charge. Are Muslim societies going to be perpetually caught in a pendulum between authoritarian rulers, and the counter-reaction to those leaders? Do we need another ISIS which responds to his authoritarianism with even more extremism?

The Saudi political system is unique and the clerical class are a vital pillar of the Saudi state, the state’s identity and even its raison d’etre. In some ways, religious opinions are then a matter of national security. Do you think these reforms are possible if scholars are permitted to dissent, or is there a wider issue about the nature of the relationship between the state in Saudi Arabia and the clerical class who define orthodox religion?

This reminds me of the issue that Jamal Khashoggi was deeply and seriously concerned about in his later career. Saudi Arabia now says it opposes political Islam. Khashoggi found this incredibly incoherent, though he put his criticism very politely, but he said “Saudi Arabia is the mother of political Islam.” So, if it is now against political Islam, what accounts for the legitimacy of the Saudi state?

We all know of the deep relationship that exists between the Saudi royals and the clerical class which goes back to the founding moment of the Saudi dynasty. They depended on each other in what was a symbiotic relationship. But we have to remember that regardless of how a state is formed, there are modern imperatives for the need to build a real nation-state. The usual story of the emergence of a state is that of a singular visionary ruler committed to a creed, to the eventual development of a society which creates a space for a plurality of views and lifestyles. And this requires strong robust civic institutions and a civil society.

If he really wanted reform and was listening to people like Jamal Khashoggi, he would have empowered young, educated Saudis, who have also been calling for a constitutional monarchy, rule of law and the development of an independent civil society. If you look for example at what some of the Saudi women who were thrown in prison and tortured were advocating for, they were not calling for the throwing out of Islamic law, but a more appropriate re-interpretation for the current conditions of their society.

“We cannot ignore the fact that young Saudis today are among the most educated people in the world. This is an important fact, because what Mohammed bin Salman is doing is denying the development of meaningful civic institutions, and an independent civil society by freezing Saudi Arabia through the growth of his despotic style of rule.”

We cannot ignore the fact that young Saudis today are among the most educated people in the world. This is an important fact, because what Mohammed bin Salman is doing is denying the development of meaningful civic institutions, and an independent civil society by freezing Saudi Arabia through the growth of his despotic style of rule.

People who support Mohamed bin Salman’sdespotism are projecting an image of Muslims and creating the conditions in which their projection comes to pass. Their perspective is that Muslim societies cannot change and they do not grow or evolve organically. And it is these same circles’ support for these dictatorial rulers that is keeping us in this dark age for Islam.

*The interview has been edited for clarity.

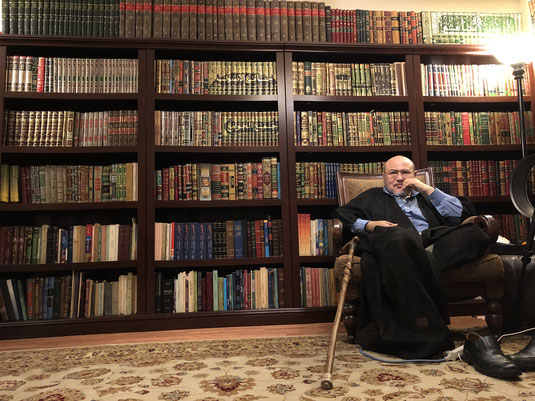

*Image: Professor Khaled Abou El Fadl sits in his library in Los Angeles, where he often delivers sermons to a local and international audience. (Courtesy: Usuli Institute)