The Library of Congress (LOC) recently acquired and made publicly available online a unique collection showing the only known surviving slave narrative written in Arabic in the United States.

The Omar Ibn Said Collection [1], which consists of 42 digitized documents in both English and Arabic, including a fifteen-page autobiography of Omar Ibn Said himself, sheds further light on the history of Islam in America and the enslaved Africans who were brought to America during the transatlantic slave trade.

The earliest iterations of the collection was created thanks to the efforts of Theodore Dwight Weld, a prominent abolitionist and the first secretary of the American Ethnological Society, who knew of Said and other enslaved African Muslims.

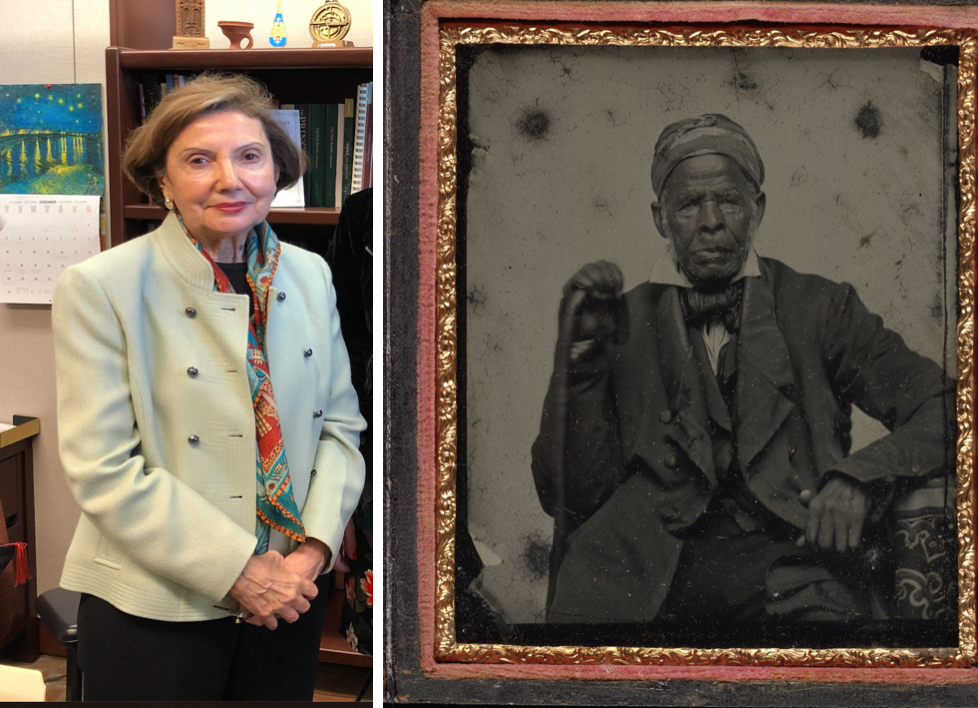

Isil Acehan from the Maydan team interviewed Dr. Mary-Jane Deeb, Chief of the African and Middle Eastern Division at the Library of Congress, about the Omar Ibn Said collection and its significance.

The Omar Ibn Said Collection At the Library of Congress | An Interview with Dr. Mary-Jane Deeb | By Isil Acehan | The Maydan from Ali Vural Ak Center for Global I on Vimeo.

____________________________________________________________________________________

Could you please tell us about the acquisition process and where the collection came from?

This is a collection of forty-two documents. And the Library bought it from Sotheby’s in London. But we were aware of this collection before and we wanted to acquire it. And this collection included acritical document, Omar Ibn Said’s autobiography. It was shown in the library in 2002 at a conference on Islam in America. The conference focused on how Islam came to America; when did the first Muslims arrive and who were thesefirst people. So it turned out that the first people were from Africa because they were brought in as slaves. And then afterwards came the others, from Asia, from Europe, from the Middle East and so on. But they came much later, more in the nineteenth and the twentieth century. But the early groups that came in the seventeenth and eighteenth century came from West Africa. So we had a number of scholars who attended the conference and each one was talking from a different perspective. One of these scholars brought in this manuscript of Omar Ibn Said and he said “…here is a manuscript by a West African, who is a scholar, and who was a wealthy man. And so on. And then he was caught and shipped off to South Carolina.”

And he wrote his memoirs. And so the person who had this manuscript said “I wish one day that this manuscript would be at the Library of Congress.” That was in 2002. And we said we wish we had this manuscript. But he was not selling it. And we were not buying it. We had no money at this point to buy this manuscript.

So, fast forward, fifteen years later in 2017, the owner let us know that the manuscript was for sale at Sotheby’s. And he was very sick. And he said “you have to buy it. You have to buy it because some other country is going to buy it and it should be in the US. It is an American story and it should be in the Library of Congress so that everybody can see it.” So the Library did find the money to buy it and we purchased it in the summer of 2017.

It is a very important manuscript because it changes the narrative on slavery. In order to justify enslaving another human being, human beings had to be dehumanized. They had to be stripped of their culture and their history. You know this happens sometimes in war times, when people dehumanize the enemy to be able to shoot and kill. This story brings back the humanity, brings back the dignity of the people who were brought by force against their will to be slaves in America. It adds a context. They would say, for example, the people in Africa had no written culture. It is not true. He proves not only that they had a written culture, but it also goes a long way back. They would say they had no educational institutions. Well, he spent twenty-five years learning. He went to Islamic schools and after twenty five years, after learning how to read and write, he must have learned astronomy and medicine and science. Because if you spend twenty-five years in school, you go beyond writing and reading. So he was a scholar in the full sense of the word.

Also it disproves the idea that they are all a poor people in Africa.. Well, no, he was wealthy. He was wealthy and in his biography he says “I am Muslim and I went on pilgrimage and I gave zakat.” And then he describes what he gave. He gave gold, he gave sheep, he gave cattle which means he must have been a very wealthy man to be able to give this for charity. You see. So we get a completely different picture of who was taken in.

We also have the Theodore Dwight papers. We not only have the Omar Ibn Said collection, but we also bought the correspondence around it. So there were Americans who wanted to educate the American population about what they were doing, who they were bringing in and they were against slavery.

And so they took this autobiography and they had it translated and sent it to different people. Now we have this whole correspondence in the collection at the Library of Congress.

When did Omar Ibn Said write and when was it translated?

He wrote his autobiography in 1831. Then from the 1830s to the 1860s, this autobiography travelled. For example, they wrote to certain people who knew Arabic, like Daniel Bliss, who established the American University of Beirut, which was called at the time the Syrian Protestant College. They wrote also to Isaac Byrd, who was also an American from the East Coast, who knew Arabic and they did some translations. Then they contacted the presidents of Liberia. Liberia as you know, is the country that was created for the freed slaves of America to go to. And so we have with this collection the correspondence of two presidents of Liberia who corresponded and who said “well, yes; we know about these manuscripts, we have people here we have a lot of manuscripts as well.”

And we know now that there are hundreds of thousands of manuscripts in Arabic throughout Africa. It came with Islam. It came seven hundred years ago, through trading. We have, for example digital copies of manuscripts from Mali, from Timbuktu. They are in Arabic and focus on issues in Mali. One focuses for example, on how to make peace between two conflicting tribes. It speaks about medicinal plants and how they help. It talks about the stars and astronomy. It talks about travel in the desert.

So these manuscripts are priceless in terms of the value, in terms of the knowledge that they bring to it. So I am hoping that what is going to come out of this collection is that it will inspire young people. We have had two big school groups who look at these manuscripts in Africa and have preserved them because you know they disintegrate eventually with the dampness, with the heat, the dust,the insects, etc. They have to be preserved Although these manuscripts, to tell you the truth, are better in terms of quality then modern paper, because the way that they made it. They wrote on them with plant ink, not with chemicals. They are written on goat skin, which is very resistant. It’s not like paper that becomes yellow and brittle. So the quality of manuscripts we have here in the Library of Congress go back a thousand years.

Of course manuscripts are in other places too. Turkey has a fantastic collection; manuscripts at the Topkapi Palace library are world famous. They are among the most important collections in the world. And you know the importance of preserving these materials.

But in Africa there needs to be a system to preserve them. The Middle East has been making an effort, Turkey has done a fantastic job. Now there must be a major effort at the international level to rescue these manuscripts. And so I hope that this little manuscript will open the door and bring more interest to those types of materials in Africa.

And how about the family of Omar Ibn Said? His brother was a sheikh right?

This is a very interesting issue. In his manuscript, he refers to his brother as being one of his teachers. He speaks about his father and his father having several boys and several girls, and about his mother.

What happened to them?

He does notsay. He also was captured at the age of 37. He must have been married. He must have had children. And perhaps it is because he is afraid that something would happen to them as he was enslaved. He was afraid that something could happen to them too. So he never speaks about them. And then he comes to America and he’s encouraged to get married. And he never gets married. So there are no descendants, there is no family. And we only know about his father, and his uncle. His father is killed when he was only five. And we do not know what happened to his siblings. We do not know if they were caught up too…But it seems that he is the only one who is actually enslaved and brought to America.

Did he practice Islam in the US?

My guess is that he must have prayed. I do not know that there was a mosque for him to go to. But you know, when he was asked to write the manuscript, his autobiography. The first thing he does is to write a verse from the Quran. It is Surah Al-Mulk, the sixty-seventh chapter. And I wanted to check myself, so I put the Koran in Arabic and I put his autobiography next to one-another for compraison. And he had it right by the memory.

He wrote the whole chapter, thirty verses of the chapter. There is only one verse where he forgot three lines. Imagine, as an old man he could remember, he could still remember the whole thing and he wrote it down.

So you know the rest is his own story. He is supposed to have converted to Christianity. Some people said he did not, because he was afraid, he was a slave. So he did not convert. But my reading of it is that he was very good at seeing what is good and what is evil.

So for example, he said the first man who owned him was a bad man. He did not believe in God. He was not good. But the second one, where he spends the rest of his life, was a good man but he was a Christian and he had the Bible. He would read to him.

He could make the difference between the two. And I have a feeling, and it is my own interpretation, perhaps a bit different than others who said he did not convert. He speaks about reading the Bible. He speaks about going to the church but he also speaks about the Quran. And he saw what is similar, what is in common, and what both religions share. And he was a philosophical man. So he saw the essence of both religions.

So to him, I think from what I could read, was that he saw what is good, what is right. Whatever the religion, he was comfortable in both.

Why Surah Al-Mulk? Why would he start (the autobiography) with that if he had converted to Christianity? And I would say because, Surah Al-Mulk is the chapter on Dominion. But also “Mulk” means ownership and in Islam as you know all ownership belongs to God. God is the sole owner of everything. So it is a basic criticism of slavery. You cannot own another human being. He does not say it. He simply implies it by selecting this verse. So he is very subtle in his criticism.

I think there is so much that can be researched, that can be opened, that can be interpreted. And then there are other writings and they seem to be in other institutions. And one of the things I hope to achieve by having a website ewhere we can link to other items in other institutions. If someone has a letter, or a book, we can link these online. They can keep the original document but if it is digitized we can connect them and we can expand our collection.

Are all the documents in the collection in Arabic or are some of them translated?

As far as I know everything he wrote was in Arabic. I do not think he wrote in English.

Did he speak English?

I would assume he did. One of the speakers at the panel we organized today said he did not. But how would he not know English after forty or fifity years in America? Even in the document he says that the wife of the owner would read to him the Bible. She would read to him in what language? It had to be in English and if she read it to him, I think he understood it.

So my guess is that he did know English but he chose to write in Arabic. That is why I think it is more truthful, more candid, because he was not afraid to write in Arabic because no one could read it, so he could write freely. So that is the importance of this manuscript.

Thank you Dr. Deeb.

Dr. Mary-Jane Deeb is Chief of the African and Middle Eastern Division at the Library of Congress. She joined the Library in 1998, as Arab World Area Specialist, and later became Head of the Near East Section. She helped establish Rockefeller Fellowships for Islamic studies at the Library of Congress, led a Library of Congress mission to Baghdad to assist with the reconstruction of the National Library of Iraq, and in 2004 accompanied the Librarian of Congress on an official visit to Iran. She has also co-curated several Library of Congress exhibits since 2010, including one on “Voices from Afghanistan,” and another on “A Thousand Years of the Persian Book.” Before joining the Library of Congress she was the Editor of The Middle East Journal, Director of the Omani Program at The American University in Washington D.C. where she was teaching, and Director of the Algeria Working Group at the Corporate Council on Africa. She has also taught at Georgetown University and at George Washington University.

[1]https://www.loc.gov/collections/omar-ibn-said-collection/about-this-collection/