The first version of this esay was presented at the Middle Eastern, Islamic, and Ottoman Studies Graduate Student Colloquium 2022 held online by The Institute of Middle East and Islamic Countries Studies at Marmara University and the AbuSulayman Center for Global Islamic Studies at George Mason University.

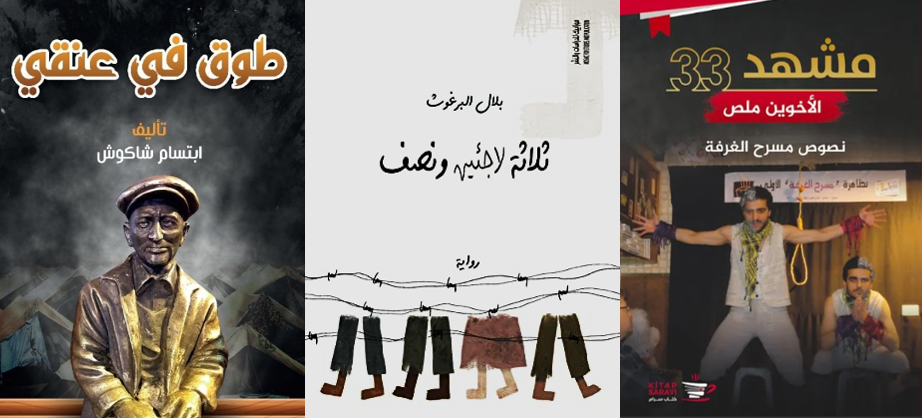

In a realm where fantasy and reality collide, the fictional characters written by Shākūsh, al-Barghūth and the Malas Brothers give voice to a largely silenced refugee population. In each story, the context is that of a host country, the time is one of estrangement. Shākūsh’s narrator is standing in Gaziantep, Turkey watching a statue and hoping it will speak to her. Al-Barghūth’s Sāra is carving her name on a random tree in Bulgaria as she waits for the smuggler to finish his break and continue their way to Holland. The Malas Brothers’ One is in a small room in Paris listening to music and practicing his French. They all share a sense of unease, even alarm, as they don’t know what to expect of the unfamiliar surroundings and unfamiliar people. They’re far away from everything they knew, unsure of what their next step might be on this refugee journey. Nonetheless, none of them are fearful or hesitant. In fact, the characters act on impulse, often without thought about the consequences of their actions, since there is simply nothing left for them to lose. Shākūsh’s narrator, upon leaving the statue, wanders the streets looking for a place to stay or work. Sāra, after being abandoned by the smuggler, manages to escape from armed men trying to kidnap her, and wakes up the following day in the house of a Bulgarian gypsy family. The Malas Brothers’ One, is interrupted by his roommate Two, engages with Two in a lengthy satire of the refugee situation in France, and they converse, shout, cry, sing and dance. All these characters are heroes in stories of Syrian refugees. Their creators are Syrian refugees themselves, seeking to tell the world the untold stories of what they lived through and what they witnessed. This essay will deal with an aspect of the untold in Syrian refugee stories by analyzing the literary works of these refugee writers: Tawq Fi ʿunuqī (A Noose around My Neck) by ’Ibtisām Shākūsh, Thalāthatu lāji’īn wa niṣf (Three Refugees and a Half) by Bilāl Al-Barghūth, and Les Deux Réfugiés (The Two Refugees) by the Malas Brothers. Whereas the usual focus when analyzing refugee narratives is on the characters and plot, this piece contends that the host country is a critical yet untold aspect of the refugee experience, and should be considered as a character nearly as important as the main refugee characters themselves. There is a tense dynamic, a give and take, between the characters and the countries hosting them. In the stories that will be tackled here, these settings are: Turkey, Bulgaria, and France. Over the course of three works, the host country always seems to offer a Pandora box that contains either a present or a trap. That dual nature of the host country’s offer is, I argue, best analyzed through by applying Derrida’s concept of hostipitality.

Derrida’s Hostipitality:

But Derrida does not talk about this transformation merely in relation to the contract. For him, hospitality, in its very definition, is self-destructible.Derrida’s term hostipitality builds off of the idea of hospitality as being a law, a right, and an obligation. According to Derrida, hospitality is not a favor that the host extends nor is it a free gift to be used at leisure by the guest. There is a contract that binds host and guest. The guest has a right not to be treated unfairly when he enters someone else’s home. The host, on the other hand, has a right to retain authority therein. The relationship that brings the host and guest into common terms is one of give and take. The host can only become a host by “being welcomed by him whom he welcomes,” that is, he/she can only have their role fulfilled by the coming of the guest. And giving the host that role, the guest, in turn, plays his/her own role by following the conditions set by the host, speaking the dictated language, for example. Based on the application or the violation of this contract, hospitality may turn into its opposite: hostility. But Derrida does not talk about this transformation merely in relation to the contract. For him, hospitality, in its very definition, is self-destructible. It has its negative opposite within itself and cannot escape it unless it is put into practice. Hospitality is hostility until it is acted upon, hence the term hostipitality. Derrida gives many synonyms to the concepts of ‘host’ and ‘guest’, each denoting a possible scenario of hostipitality. In hospitality, the host may be a ‘father’, in which case the guest becomes a ‘son.’ In hostility, the host may be a ‘master’ letting in a ‘slave’ to his house. In treating the guest in the way a master treats his slave, the host violates the contract. But the key here is the latent potential of both outcomes within the same initial act of welcoming a guest into one’s home.

Hostipitality in Refugee Stories:

In the refugee stories, Derrida’s hostipitality can be found in its different shapes. The positive form of it, the form of hospitality, appears in Shākūsh’s work. The wandering narrator, who reaches a point of loss and desperation in Gaziantep, finds welcome from a Turkish woman called Meryem. Meryem speaks Arabic with the narrator, takes her into her house and gives her a room. Whenever the narrator is out wandering, Meryem calls to check on her and ask her to come back. With every call from Meryem, there is a tension building: will the narrator decide to return or take a new step? Meryem gladly receives the empty-handed narrator who comes back again and again after her failed trials in Antakya, Reyhaniye and Istanbul. The final step is the narrator’s decision to travel to Egypt, upon which she bids Meryem farewell, describing her as “the beautiful, pure face of Turkey” that she will never forget. In this story, Meryem the Turkish woman is the host of both a nation and a house. Not only does she welcome the narrator into the country, but she also enables her to cross a second threshold into her house. If Derrida describes the host to be a ‘father’, then Meryem is very fit for a ‘mother’ who cares for her ‘daughter,’ the narrator.

Of course, not all refugees are fortunate like Shākūsh’s narrator. The negative form of Derrida’s hostipitality is quite prevalent in al-Barghūth’s short story collection. Sāra’s original destination on her refugee journey is Holland, but that plan is interrupted by armed men on horseback who attempt to kidnap her. She narrowly avoids capture and is then found by Bulgarian gypsies who invite her to their house. Although everyone in that house likes Sāra, the man of the household believes that “strangers bring troubles.” Sāra isn’t able to to keep them out of danger by surrendering to the same men who tried to kidnap her before. These men turn out to be a gang that uses the refugees they capture in their political plans to win Parliament elections and increase their influence in the country. They make Sāra lure a Bulgarian football player whom they plan to make their candidate in future elections. The football player falls in love with Sāra but also becomes ill and dependent on her, something of a bittersweet ending for her rough journey. In his other stories, al-Barghūth shows harsher situations of hostility towards refugees, including violence and rape. The hosts in these stories are the masters of Derrida’s hostility who look at their guests as ‘enemies’, ‘slaves’, or ‘parisites.’ They make use of the characters’ bodies in order to achieve their goals. Here, there is no talk of the right of guests or a contract to be made between hosts and guests. There is only hostility.

Between the two extremes of hospitality and hostility, the refugee may find either ease or hardship. The refugee experience, however, is not always that simple and one-sided. Both situations can occur in one and the same host country and, in that sense, the meaning of Derrida’s hostipitality is much more applicable. The Malas Brothers portray the complications that refugees face, albeit in a less serious tone than that of Shākūsh and al-Barghūth. Black humor is their way of talking about the refugee life. The characters, One and Two, are refugees of different origins who converse about their experiences in France in the French language they are struggling to learn. They portray France in contradictory ways. France appears first in a Peugeot that hit Two and hurt his head. The French nurses who tend to Two’s injury are “beautiful,” “nice,” and “calm” and this makes Two feel better about getting hurt. In another account, One mentions a French man who told him he was a “foreigner” and that, for him, means something less than a “human being.” He sadly adds that “foreigners” are only given houses underground, such that their lives in Paris never seem to have a sunrise. Right after that, he receives a letter from the social office about refugee work benefit and he becomes excited. Through these bits and pieces of inconsistent information, the host country in the Malas Brothers’ work appears to be on a thin line between hospitality and hostility, showing a different treatment for the refugee every day. One day, it can act as a loving ‘parent.’ Another day, it turns into a hateful ‘master.’ This thin line is a manifestation of Derrida’s concept of hostipitality and explains its dual, contradictory nature.

The host country in the Malas Brothers’ work appears to be on a thin line between hospitality and hostility, showing a different treatment for the refugee every day. One day, it can act as a loving ‘parent.’ Another day, it turns into a hateful ‘master.’

In response to either and both of these treatments, how do refugees as “guests” fulfill their role in the hostipitality contract?

The Refugee Response:

Before looking at how refugees take part in the hostipitality contract, an account of how refugees are expected to act and exist in host countries should first be given. From the perspective of international relations, the refugee has a different identity than that of a “guest” or a “slave.” Nation-states, being protective of their geographical borders and insistent on preserving the communities they consider as “citizens” deem the refugee as a “phenomenon” that demands international attention and a “problem” to be solved. In order to solve this “problem,” the UNHCR suggests durable solutions in one of three ways: voluntary repatriation, local integration, and resettlement. This means that refugees, if they do not wish to go back to their original countries, must integrate in the host country or move to another “third” host country where they can more easily integrate. The host countries’ treatment of the refugees in their lands, thus, must relate to this condition. By being hospitable, hostile, or both, the host countries push the refugees to act and do something about their ambivalent identity. And when returning to places stricken by conflict and war seems impossible, local integration becomes the only available option for refugees. But in their response to hostipitalities, can refugees really integrate? Shākūsh’s narrator, Sāra, One and Two help answer this question.

Shākūsh’s narrator, upon receiving hospitality, fulfills her role in Derrida’s contract by appreciating the host and acknowledging the temporariness of a guest’s stay. “Their generosity makes me shy,” she says, “For how long does a guest stay in his host’s house? It has been a long time. I have to resolve this knot.” Interestingly enough, that is the only instance in the story where the narrator’s role as a guest can be noted. The nation-state’s wish of refugee integration is completely absent from the narrator’s mind. The plot line, as a whole, revolves around the narrator resolving that knot of her residence and, more specifically, about herself as a lost refugee somewhere in this world. Apart from Meryem, there is almost nothing else about the narrator’s relation to the Turkish people or to Turkey. The statue in Gaziantep that the narrator converses with is not important for its own sake. It is important because it reminds the narrator of her grandfather. The streets are clean, full of trees and flowers. Yet, they are only interesting for the narrator because she recalls that there is nothing like them in Syria. The narrator is indifferent about knowing the language. She does not interact with the Turkish community as much as with the Arab refugee community. Settling down in Turkey, for her, is merely one option among many. Once a friend suggests Egypt as an easier place to find settlement, the narrator does not hesitate to leave Turkey altogether. Without giving more thought of the host country’s hospitality and almost any thought of integrating, the narrator prefers to stay on the move, focusing on herself and safeguarding her identity.

Sāra, in al-Barghūth’s work, fulfills her part as a guest only towards the few Bulgarian people who help her. By surrendering to the gang, she saves her friends and ends her temporary stay at their house. With the hostility that follows from then, the contract is broken and Sāra turns into a serving object for the gang, which detaches her from the guest role. Despite the difference in context and plot, there is a similarity to note between Sāra’s reaction to hostility and the reaction of Shākūsh’s narrator to hospitality. The center of the plot is Sāra, her thoughts, feelings and decisions. From the beginning of her journey, Sāra carves her name with the key of her destroyed house in Syria everywhere she goes. Over the highway in South Bulgaria, in Sofia, and in Holland, she witnesses the events occurring around her, engages in them by making friends and enemies, but she never changes anything in herself nor lets anyone make a change in her. For her, the host countries she enters do not matter, whether they be Bulgaria or Holland. The host communities she enters do not matter either, whether they be a small gypsy family or a prostitution ring. What matters is the next step she decides to take and the sacrifice she has to make in order to pursue her life. Again similar to Shākūsh’s narrator, language for her is not a problem because wherever she goes, she finds people who can speak English with her. As long as she can keep surviving, Sāra is a free spirit, not minding a life on the move. Here is another refugee character who responds to the host country from a distance, preserving her own identity without integration.

For her, the host countries she enters do not matter, whether they be Bulgaria or Holland. The host communities she enters do not matter either, whether they be a small gypsy family or a prostitution ring. What matters is the next step she decides to take and the sacrifice she has to make in order to pursue her life.

In contrast to the nomadic lives of Shākūsh’s narrator and Sāra, One and Two seem to be very much settled. They are refugees in France, they have a residence permit and health insurance, they share an apartment and they are learning French. They are not new to the host country and they seem to fulfill their role towards France’s hostipitality contract perfectly. When we first see them, they both look moderately happy as they laugh about the difference the type of car makes in hurting Two’s head and correct each other’s language mistakes. Being a dark comedy, the “dark” part of the play starts to appear when there is “silence.” One says: “I miss mum” and Two replies: “I miss mum.” This part is repeated throughout the play in different forms, shattering any possible perception by the audience of France as a Utopia for refugees. “When I arrived in Paris, I thought Paris is the city of theater, love, and human rights. But the social worker told me you are a foreigner!” One says. “When I first arrived in Paris and went to Barbes I thought, is that the city of love or weed?” Two says. With this shattered perception, One and Two learn the French language, but learn to curse it too. They praise the French people, but satirize them in the same breath. They wish to become French, but only to be able to leave France, “travel to Italy to eat pizza, then to Germany to buy three Mercedes! then to Brazil!” And so, even if they comply with all the conditions of guesthood, and even if they may seem to have a wish to integrate, they know that doing so would require being dishonest with themselves. They are in reality sad and lonely. To overcome their sadness and loneliness, they dance. The scene description tells the audience that: “they start dancing as if they were back in their countries and they take off their clothes. They only keep what makes them look similar.” Assimilation is a mere facade. Unmask the facade and the truthfulness of the refugee’s unconfined essence emerges.

If thought of in international terms, these characters remain a “phenomenon” and a “problem” that does not seem to have a solution. In the writers’ terms, however, they are the free and the unconfined in any place outside their homelands. Their bodies are expected to conform but their minds and spirits accept no rules and no borders. They are guests as much as Derrida’s guesthood applies, but they respond to their hosts’ hostipitality from a distance, demanding a respect for their subjectivity. An aspect of the untold in refugee lives is thus brought to light and there is still much more to reveal. These names are only a few among many refugee heroes that can be found in the literature of Syrian refugee experience. Refugee voices are increasingly rising to spread awareness regarding refugee lives. Now they just need to be heard.

If thought of in international terms, these characters remain a “phenomenon” and a “problem” that does not seem to have a solution. In the writers’ terms, however, they are the free and the unconfined in any place outside their homelands.

Sena Taha is a PhD student at the Alliance of Civilization Institute at Ibn Haldun University in Turkey. Her dissertation is about Refugee Literature, focusing on the Syrian literary productions concerning the refugee experience.