This essay is being published as apart of the Islam on the Edges research portfolio hosted on the Maydan as a collaboration of the Center for Islam in the Contemporary World at Shenandoah University (CICW) and the AbuSulayman Center for Global Islamic Studies at George Mason University (CGIS). Learn more at themaydan.com/2022/01/edges/ and submit pitches to publish@themaydan.com.

In the aftermath of the Ottoman defeat in the Russo-Ottoman War (1876-77) and the subsequent Congress of Berlin (1878), an autonomous Bulgarian Kingdom was established. Although initially, most of present-day Bulgaria was still under Ottoman rule, this quickly changed as the Balkan Wars (1912-13) brought an end to the near-500 year Ottoman control of the region. and allowed the Bulgarian Kingdom to extend its borders. Despite atrocities committed against Muslim villagers and mass migrations to Thrace and Anatolia, there remaining about 3 million Muslims living in the Bulgarian Kingdom.

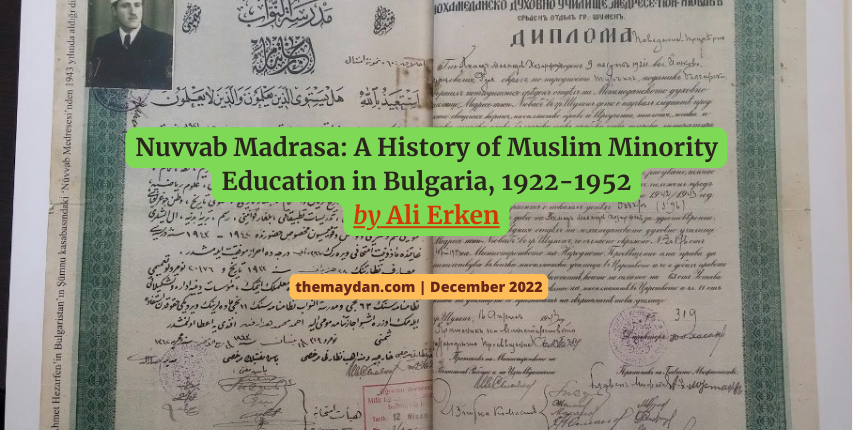

The Ottoman Empire and Bulgarian Kingdom signed the Istanbul Agreement in 1913, which involved an article on the regulation of the Institution of the Mufti in Bulgaria. This article would allow the formation of institutions for the education of Muslim religious minority. A year later the World War broke out and no further steps were taken, but finally in 1922, Medresetu’n-Nuvvab (Nuvvab Madrasa), the first Muslim institution of higher education in Bulgaria, opened in Shumen (Şumnu).[1]

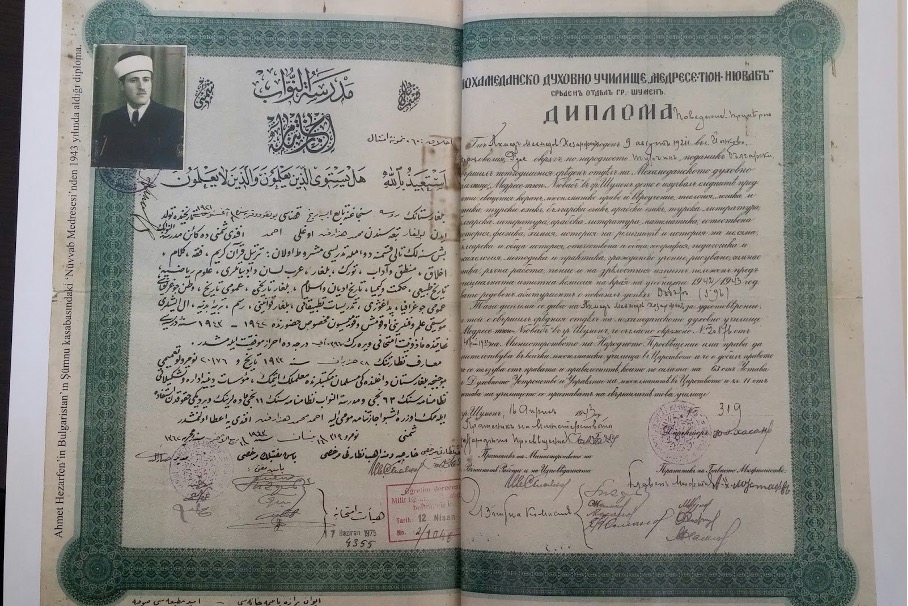

The Ottoman Empire and Bulgarian Kingdom signed the Istanbul Agreement in 1913, which involved an article on the regulation of the Institution of the Mufti in Bulgaria. This article would allow the formation of institutions for the education of Muslim religious minority. A year later the World War broke out and no further steps were taken, but finally in 1922, Medresetu’n-Nuvvab (Nuvvab Madrasa), the first Muslim institution of higher education in Bulgaria, opened in Shumen (Şumnu).[1] This region was historically inhabited by Turkish Muslims and is located near the Danube River in Northwestern Bulgaria. Today, during the 100th anniversary of its opening, and thanks to an increasing volume of biographical accounts, we have an opportunity for unprecedented access to the history of the Nuvvab Madrasa. For instance, Ismail Cambazov, one of the most prolific scholars on the history of Muslims in Bulgaria, was a student at the Nuvvab Madrasa and penned his own memoirs. Some other prominent scholars from the Nuvvab Madrasa such as Ahmet Davudoğlu and Osman Kılıç likewise published their memoirs. In addition, the availability of oral sources and other primary archival documents offer detailed accounts on the school’s curriculum, social life among the members and political tensions of the time.

Formation, Curriculum and People (1922-1945)

Following World War I, Alexander Stamboliyski formed a government with pro-peasant allies in Bulgaria. During his tenure as Prime Minister, Stamboliyski granted new rights, especially in the area of education, to the Muslim community. Süleyman Faik Efendi, the first elected head mufti for Muslims in Bulgaria after the War, who remained in service from 1920 to 1928, enjoyed good relations with the Prime Minister and established a new code of regulations for the mufti institution. As a result, the government decided to open a school for the Muslim community, as arranged in the Istanbul Agreement, and a commission was convened to decide the content of curriculum. However, the main purpose of the school (whether to train imams or teachers) was not clearly defined. In fact, there were differing views among the Turkish community itself, which could be roughly grouped modernist, traditionalist and secularist camps. The early curriculum of the school mirrored this division and included long hours of classes in basic sciences and other non-religious courses. Culture and science classes accounted for 54 hours, language and literature classes accounted for 53 hours, and religious studies accounted for 30 hours.[2] Nuvvab Madrasas in the late Ottoman period were originally opened to train judges (kadı) only, but in this new context in Bulgaria, the school would serve a number of purposes. It would accept students from traditional madrasas, and rüşdiye schools, which were offering education in rather modern subjects. This division traced back to the late Ottoman reforms in education. Interestingly enough, unlike in Bulgaria, madrasas in Turkey were closed in 1924. In the Nuvvab Madrasa, therefore, students from a madrasa background could acquire an advanced education in religious sciences.[3]

The school consisted of two branches, higher (ali) and secondary (tali) programs. It was possible to enroll in the ali section only after finishing the first four years. To be able to serve as a judge (kadı) or mufti, one had to finish the ali section. The curriculum involved courses on the Qur’an, Islamic law, Arabic language and literature, Persian language and literature, Turkish language and literature, Bulgarian literature, Islamic history, logic, philosophy, ethics, Islamic calligraphy, math, science and chemistry. During the second four years, courses on the Islamic Sciences became more rigorous, and each year fundamental books of the Islamic madrasa curriculum such as Ihtiyar, Lubab, Haleb-i Sagir, Minyetu’l-Musalli, and Mecelle were all taught. In 1928 the school of Daru’l Muallim was closed and the Nuvvab Madrasa had to serve as an institution to train scholars as well. After 1932, graduates of the Nuvvab had the right to serve as instructors and teachers, and many of them did not only serve as Imams, but also as teachers.

According to Cambazov, the Nuvvab enjoyed a high popularity among the Muslim community in Bulgaria and people were eager to send their children there. As he explains, the manner in which students dressed in turbans and robes, and their behaviour on the streets, convinced him that Nuvvab was the right school for him to attend.

The first principal of the Nuvvab was Emrullah Efendi, a graduate of the Darülfunun in Istanbul and native of Deliorman region bordering the Balkan Mountains. He taught philosophy and Arabic classes, but mostly dealt with administrative duties and managed to maintain good relations with the Bulgarian authorities. Emrullah Efendi strongly defended the inclusion of Islamic science into the curriculum, despite criticisms against himself and attempts to design a more secular curriculum. The early generation of scholars involved Süleyman Sırrı Efendi (Tokay),[4] Ali Kemal Efendi (Balkanlı), Mustafa Hayri Efendi, Ziyaeddin Efendi (Ersal) and Hasip Safveti, who acquired training in Ottoman institutions. Some of the later generation of scholars, who started to teach after the 1930s, were educated at al-Azhar University in the 1930s; Ahmet Efendi (Davudoglu), Ziyaeddin Efendi, İsmail Efendi, Osman Efendi (Keskioğlu) and Muharrem Abdullah Efendi (Devecioğlu) all came from Azhar and took up teaching posts at the Nuvvab. Some were influenced by recent modernist trends, while others, like Ahmed Efendi, were strict followers of the traditionalist school. These differences, however, did not prevent them from working together and raising the quality of the education the school provided, especially in its ali branch.

According to Cambazov, the Nuvvab enjoyed a high popularity among the Muslim community in Bulgaria and people were eager to send their children there. As he explains, the manner in which students dressed in turbans and robes, and their behaviour on the streets, convinced him that Nuvvab was the right school for him to attend. In 1940-1941, the number of new enrollments reached 161, with a total number of 331 students. This popularity could be partly attributed to the social position of the scholars and graduates, who would take jobs in mosques, schools and other institutions of teaching. Overall, 677 students graduated from the Nuvvab Madrasa between 1926 and 1947. As a result of the school’s flexible structure, graduates were able to play key roles in addressing the problems of the Muslim community, including legal disputes. In the early 1940s, the school’s graduates started to join the faculty staff, such as Osman Kılıç and Ahmed Davudoğlu.

.

The Communist Era (1945-1952)

The Communist takeover in Bulgaria proved to be a defining moment in the history of the Nuvvab. Upon taking office, the new government immediately overhauled the curriculum, the teaching staff, and the school code of conduct in an attempt, according to Cambazov, to make the school more communist-oriented. At that time, the division between students coming from madrasa and normal school background still existed, which affected the way they approached these changes.[5] To Cambazov, students were successful enough to compete with the best Bulgarian High School, but in 1947 the name of the Nuvvab Madrasa was changed to the Nuvvab Turkish High School.

Cambazov describes how the government’s brigade programs, introduced to support village infrastructure and organize cultural activities, changed young people’s perceptions and behaviour. The Bulgarian officers pressured Muslim students, boys and girls, to dance together so that they started to play tango together in the camps. The use of alcohol among Muslim students was strongly encouraged, they were invited to spend nights at entertainment venues, drink wine and mingle with Bulgarian friends. It was these types of activities that appealed to Cambazov as a young man, and he recalls the occasion when a Bulgarian friend offered him a glass of red wine for the first time. He believes some of these Bulgarians were sent by the communist party, who befriended Turkish students in the school and could speak Turkish well. They were distributing booklets discussing the “origin of world” and “creation of man,” which promoted Darwinian views, refuting the idea of single creator and existence of God.[6] They also distributed books by Lenin and Stalin so that students could gradually become more familiar with communist views. Questioning some of the arguments he encountered, Cambazov asked advice from his teacher on Islamic law, but was unable to find a convincing answer.

As Cambazov observes, these develops triggered a gradual process by which attachment to the religion loosened and an atheistic ideology became widespread. Eventually, members of the community began changing their names and surnames, working in Bulgarian institutions and integrating with the communist regime. However, the transformation was not total or sudden, Cambazov recounts, as he tells the story of Ali from Constanta who became angry at a Bulgarian friend after getting drunk and shouted:

Do you think we are stupid, Mr. Iliya? With these drinks, these seminars, you want to take our identity with cotton wool, and turn us into mindless and heartless servants, robots. But you can’t. How many years have you been working and how many people did you mislead like us? The hearts of all our friends are full of the faith and consciousness of Turkishness that you are trying to uproot. We are Turks and Muslims.[7]

Aside from this cultural transformation, a campaign of political repression against community leaders and educated elites among the Turkish minority was underway. The trials against Ahmed Efendi (Davudoğlu) and Osman Efendi (Kılıç), two of the leading of scholars of the Nuvvab, sent a clear statement to the Muslim minority. In his book, Death was More Beautiful, Ahmed Davudoglu tells of the brutal torture and mistreatment he received from Bulgarian authorities during his jail term. He was appointed principal of the Nuvvab in 1944, and continued to serve there when the communist regime came to power, but was not able to retain his position long since the students and the new government disapproved of his leadership. There were pressures to change the dress code, prohibit turbans and robes, and restructure the curriculum. He was arrested and put into prison, and after months of torture, when he had finally lost his hope to survive, the regime released him. He had to leave Bulgaria, however, and in 1949 Davudoğlu migrated to Turkey. Osman Kılıç’s trial was yet more tense. As a strong orator and a knowledgeable thinker, he represented a prime target that the communist rulers sought to pull to their side. Kılıç was accused of treachery to communism as well as spying on behalf of Turkey, and was sentenced to death. For most of his nearly 15 years in prison, from 1948 to 1962, he was tortured and confined to a single cell. Only in 1962 was he released and allowed to rejoin his family, who had migrated to Turkey by then.

A final turning point in the history of the Nuvvab was the great migration of 1951 and 1952.

A final turning point in the history of the Nuvvab was the great migration of 1951 and 1952. The Communist regime had increased pressure on the Turkish community, and following consultations with Stalin, the government decided to force the Muslim community to migrate to Turkey. Nearly 350,000 people migrated to Turkey in 1951-1952. The top priority was to expel the Muslim educated class, and almost all of the teaching staff and graduates of the Nuvvab fled Bulgaria during that period. Interestingly enough, however, those scholars and graduates who left Bulgaria did a lot of service in Turkey, during a period when religious teaching was restricted and instructors with the requisite language skills were quite rare.

Conclusion

Scholars who were forced to leave their land mostly settled in Turkey. Ahmed Davudoglu served as a madrasa instructor, taught at Higher Islamic Institutes, and translated some basic sources such as the Sahih-i Muslim, and the Ihya-ı Ulum-i-Din into modern Turkish. Yusuf Ziyaeddin Ersal likewise authored various textbooks for theology students, which are still in circulation, such as his works on the history of Islam and the Hadith sciences. Several other scholars took advantage of their Arabic and Ottoman skills to teach in madrasas, Imam-Hatip schools, and the Presidency of Religious Affairs and Foreign Ministry. While these figures carved a new space for themselves in Turkey, the Turkish Muslims in Bulgaria were of course impacted by the loss of such prominent scholars and graduates.

Despite its eventful and somewhat rocky history, the Nuvvab Madrasa of the early 20th century can provide a model for developing Muslim religious education institutions in minority context. Further discussions regarding the school may offer Muslims living in the West today precedents regarding curriculum development, relations with political authority and community development within and beyond the Muslim diaspora.

Ali Erken teaches at Marmara University, Institute of Middle East and Islamic Countries. He holds PhD in History (Oxford), authored a book and articles on the history of modern Turkey and Balkans.

[1] Another institute of higher education, Daru’l-Muallimin, for the training of instructors was opened in 1918

[2] In a booklet defining the purpose of the school, it says “to train ulema who could meet contemporary needs and requirements”

[3] In Bulgaria madrasas and rüşdiyes were still operating after the foundation of Bulgari

[4] Many Nuvvab scholars later migrated to Turkey and took surnames. These surnames are given in brackets throughout the article

[5] Ismail Cambazov, Medresetü’n-Nüvvab, p.19-20

[6] Ismail Cambazov, Medresetü’n-Nüvvab, p.70

[7] Ismail Cambazov, Medresetü’n-Nüvvab, p.74