On December 7, 2015, I sat on a rocker in my preschoolers’ shared room, scrolling through the news while waiting for them to fall asleep, under a blanket to dim the light from my screen. Five days before, there had been a mass shooting in San Bernardino, California, during which fourteen people were killed and twenty-two were injured. The shooters were a married Muslim couple, thought to have been politically radicalized by overseas organizations. It was the deadliest mass shooting since Sandy Hook Elementary School. The nation reeled and American Muslims took cover. In the post-9/11 politics of our country, an act of violence by any Muslim was broadly attributed to us all, and to Islam itself. We were expected to, and many of us did, respond by publicly condemning the attacks, seeing no way to reject collective culpability and still convey our horror at what had happened. We had no way of saying “We are not them—we should not be held accountable for their actions.” Over the preceding fourteen years, the social space to assert this basic principle of human rights had all but disappeared for American Muslims.

The most we could hope for was to reduce the inevitable collective punishment, to minimize retaliation against Muslims and every person who might be mistaken for Muslim in our communities. In the days that followed the attack, a pig’s head was lobbed at the Al-Aqsa Mosque just North of Girard Street in Philadelphia. I knew that mosque; my friends were community leaders there. I’d helped cover the exterior of the old factory building in which it was housed with a gorgeous geographic mural. My part had been to carve the ninety-nine names for God into ceramic tile that wrapped around the building just above eye level.

During the same period, a store owner in New York was beaten and hospitalized, a Somali restaurant torched in North Dakota, and several other mosques were vandalized or sent threatening messages. Employees at the Arab American Anti-Discrimination League received death threats, several Muslim passengers were pulled off of flights, and Muslim organizations reported a broad escalation in threats and attacks across the country.

We still had to live, had to travel for and get along at work and school, had to shop and drive and be in public spaces. We pushed our worry aside and played with the kids. But we were terribly aware that in the American mind we had collapsed further into a monolith, each of us individually culpable for the misdeeds of any Muslim.

In suburban America, we opened our front doors more carefully, forgoing cultural or religious attire. More of us stopped going to the mosque. We kept our children home from school and said an extra prayer when we finally calmed our nerves enough to send them back. We kept our heads down at work and we volunteered at and donated to Muslim civil rights organizations, thinking that any day now it could be us at their doorstep. We tried to tighten the circles of our lives, make ourselves a little less exposed to the whims of the people around us. We still had to live, had to travel for and get along at work and school, had to shop and drive and be in public spaces. We pushed our worry aside and played with the kids. But we were terribly aware that in the American mind we had collapsed further into a monolith, each of us individually culpable for the misdeeds of any Muslim.

***

Eleven months earlier, on February 10, 2015, three Muslim students were shot, execution-style, by a neighbor who knocked on the door of their Chapel Hill, North Carolina, apartment. The apartment was actually home to two of them, Yusor and Deah, a strikingly beautiful, recently married couple who had grown up in North Carolina. Deah, who was twenty-three, had begun dentistry school, Yusor, who was twenty-one, was about to enter the same program, and Razan, Yusor’s nineteen-year-old sister, was studying architecture and environmental design. All three were deeply engaged in their families, their schools, and their community, outstanding students who spent their time off preparing meals for local homeless people and planning a dental relief trip abroad for Syrian refugees. These three represented all of what I, as a Muslim, a mother, and a second-generation immigrant, hoped for my children: a vibrant dedication to meaningful pursuit, guided by a deep sense of social and environmental responsibility.

The three, and other neighbors in the complex, had been confronted by the angry and armed White neighbor named Craig Hicks several times before. Both Razan and her sister chose to wear , scarves over their hair, as part of their daily faith practice. Hicks had approached Yusor and her mother on the day she moved in, telling them that he didn’t like the way they looked.

Razan was visiting her sister and brother-in-law for dinner on the evening they were killed. The police immediately framed the killings as the result of a parking dispute, accepting the story that the killer, Hicks, told without question. Muslim Americans immediately understood the murders as hate crimes, absorbing the way Yusor and Razan were shot in the head while pleading to be spared, the eight separate bullets used to kill Deah—with a final shot through the mouth, on Hicks’s way out, and Hicks’s own numerous and emphatic anti-religious statements. Deah’s sister, Suzanne Barakat, went to the media, asserting this for all of us in the weeks and months that followed, expressing how terrifying it had become to be identifiably Muslim in America.

***

The San Bernardino attack seemed to refuel an anti-Muslim rage that lived just beneath the surface of our neighborhoods, our police forces, our schools. Assaults against American Muslims were higher in 2015 than they had ever been—even higher than they had been in 2001 just after the 9/11 attacks; in 2016 they would climb higher still. In advance of the 2016 presidential elections, Donald Trump signaled that he would support a registry for Muslims, an echo from the post-9/11 period that triggered another complex layer of collective trauma.

In the years that followed 9/11, many of us drank in the narrative that the men held at Guantanamo were there because they were guilty of something horrific, that therefore our own innocence would protect us. But those of us who took a sustained look learned that most of the 779 men (and boys as young as thirteen) at Guantanamo were held without charge or trial. We learned that the majority of men and boys held at Guantanamo, 86 percent, were brought in without any intelligence by local people in Afghanistan or Pakistan in return for lavish bounties from the U.S. military, advertised on leaflets dropped from the air. Guantanamo had stretched our imaginations of what collective punishment against Muslims might look like, and how one could find oneself to be a target simply by being Muslim in the wrong place at the wrong time.

***

Under my blanket, my laptop pinged with a message from Cynthia, an old college friend living in Wisconsin. “How can I help?” she wanted to know. By then Trump was the leading contender for the Republican presidential nomination and had called for a “total and complete shutdown of Muslims entering the U.S.” His message was clear: Muslims were the problem—not a lack of gun control, not extremism, not a society without proper mental health access.

My children, three and five years old, lay just across the room, their breath soft and even.Increasingly, I wondered how my tiny girl, struggling with a chronic illness and no diagnosis yet in sight, could possibly make her way as a Brown Muslim kid in American schools. Instead of the mostly plain ignorance I had dealt with, she’d have to face prejudice, harassment, or even violence.

Heart full, I walked down to the kitchen, composing a letter in my head: “Dear Non-Muslim allies,” it began. “I am writing to you because it has gotten just that bad.” … I posted that letter on a private Facebook page, aimed at the few hundred close friends and colleagues I had from school and more than fifteen years of social justice work. The letter went immediately viral; and for several months I engaged the hopeful space that it created. I even began to think that America was my country still.

As my daughter’s condition grew worse, so did the anti-Muslim rhetoric coming from Republican candidates in the 2016 presidential election. Every time Trump pushed the line on what could be said or proposed with regard to Muslims, he brought more of the Republican Party along with him. Muslims in several of my circles spoke casually about where they’d go if things “got bad.” My apolitical sister-in-law asked me if we’d packed a “bug-out bag” in case we had to leave home quickly. Nadeem and I considered what we might do to help stem the rising tide. Should I run for political office? Go back to practicing law at a civil rights organization? But Nadeem had just begun a demanding job that, for the first time since we had children, allowed us to save something every month. Someone needed to make and keep medical appointments for our daughter and continue to balance her growing needs with those of our littlest one. That would have to be me. It was becoming increasingly evident that the most intense years of parenting were ahead of me, not behind me. We weighed leaving the Delaware Valley and giving up the dream of living near my parents, three generations all in the same place.

…About 20 percent of American Muslims are Black and many have been engaged in anti-racist struggle for generations; another 40 percent identify as Asian, Hispanic, or mixed race and had perhaps dealt with racism and xenophobia. But not all of us understood the connections between those experiences and our emerging collective reality.

Everyone was panicked, me included, but that panic, particularly among immigrant Muslims, often lacked grounding in the history of how other racial and religious groups have fared in America. This should not have been so. About 20 percent of American Muslims are Black and many have been engaged in anti-racist struggle for generations; another 40 percent identify as Asian, Hispanic, or mixed race and had perhaps dealt with racism and xenophobia. But not all of us understood the connections between those experiences and our emerging collective reality. I knew something about American history, the civil rights movement, and the evolution of immigration law, but I had never before found a way to situate myself within it. Muslims make up just over 1 percent of American society, South Asian Muslims a tiny subset of that percentage. Previously that had made me feel invisible, but now it made me feel radically vulnerable.

***

Looking back, I began to see how I had been racially identified, or “racialized,” differently by the people around me, depending on where I was and who those people were. Sometimes I passed for White, sometimes people or institutions demanded a detailed explanation of my racial identity, and sometimes I was imagined to be neither White nor South Asian but something else entirely.I began to reconstruct my path through America, recalling my experiences in each place I’d lived, studied, worked, or worshipped, looking for the redemption of America in my memories. Surely there was a place where we could be safe, where even the most helpless among us, my daughter, could flourish. Instead, each set of memories contained a distinct, vehemently policed color line. Looking back, I began to see how I had been racially identified, or “racialized,” differently by the people around me, depending on where I was and who those people were. Sometimes I passed for White, sometimes people or institutions demanded a detailed explanation of my racial identity, and sometimes I was imagined to be neither White nor South Asian but something else entirely. Because of these experiences, I was aware of the color lines, but I had never carefully considered how they had come to be drawn, and in whose blood.

The need to fully understand the segregated spaces I’d navigated and how that segregation is still enforced grew urgent. I wanted to hear the stories of the other people my country had tried to displace and erase, and to study how they fared. I wanted to see if I could possibly reconcile myself to—and more important, reconcile my children to—that truer picture of America. I learned that from the birth of our nation from a cluster of European colonies, its color lines have been wrought in a relentless series of brutal, forced migrations, sometimes across town, sometimes across or out of the country. Sometimes those migrations look like trafficking or frantic escape, sometimes like internment under armed guard, or incarceration, or decimation. I began to enumerate the several racist strategies that make and keep America segregated. From the myth of manifest destiny to racially restrictive covenants, the destruction of Maroon communities to so-called urban renewal, American history is one chapter upon another of dispossession, destruction, and dislocation.

Migration alone is staggering in its complexity—the loss of cohesive identity, culture, language, lineage—but forced migration is something else entirely. America is a case study in the forced migrations of Black and Brown people, often relentlessly enacted against the same group so that generations later, entire peoples are left to reconstruct who they are or where they might be from only the shards that remain. America is a place that habitually demands unimaginable sacrifice from its most vulnerable people: names, culture, faith, health, food, survival.

***

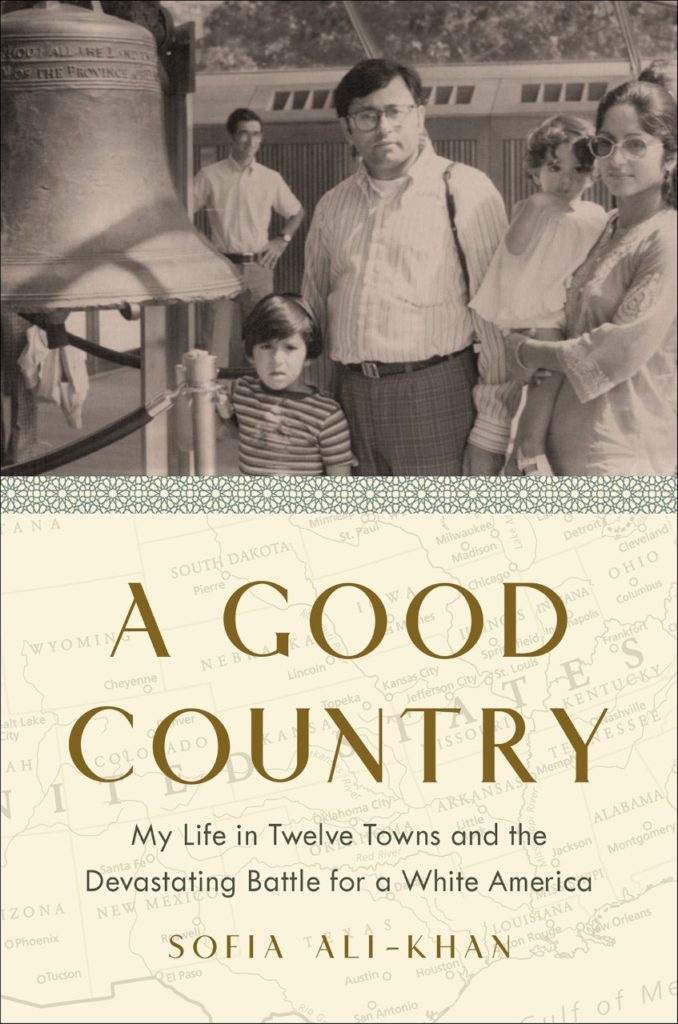

A Good Country is my recollection of each place I’ve spent time in America, and my investigations of America’s forced migrations to and from those places in the service of an ongoing colonial project. I invite you to consider what it says about America’s promise to those of us who land on the wrong side of its color lines, and to consider the euphemisms by which we are taught to accept and defend them.

A Good Country is my recollection of each place I’ve spent time in America, and my investigations of America’s forced migrations to and from those places in the service of an ongoing colonial project. I invite you to consider what it says about America’s promise to those of us who land on the wrong side of its color lines, and to consider the euphemisms by which we are taught to accept and defend them.We live not on the land that America occupies, but on the whisper-thin narrative that America is exceptionally good, that its premise is noble. Each time that narrative is pierced—as it has been again recently by Black Lives Matter protests against state violence and mass incarceration, and by Native-led and organized protests of pipelines and resource extraction that compromise access to clean air, water, and land—there is an immediate rush to patch the narrative, to maintain the pretense that America was and is for all of us. A Good Country is my effort to break through that narrative, to tell you the story of how American Muslims have become, collectively, America’s most recently racialized out-group, and to explain why my family had to leave.

Sofia Ali-Khan is a Muslim American activist, public interest attorney and the author of A Good Country: My Life in Twelve Towns and the Devastating Battle for a White America (out from Random House on July 5, 2022). She now lives in Ontario, Canada with her family.