Prologue

During the Abbasid Caliphate, Baghdad was the center of learning and scholarship in the Islamic world. Scholars from various religious backgrounds and academic disciplines flocked there to be part of a bustling society of scientists, mathematicians, alchemists, astronomers, and philosophers. They translated, transcribed, and built upon works from antiquity, conducted scientific inquiry, and engaged in dialectical discourse. The crown jewel of Baghdad was a public academy known as Bayt al-Ḥikmah — the House of Wisdom. It was a marketplace of ideas that public intellectuals came to for social and academic exchanges — a precursor to both the Italian Renaissance and the Scientific Revolution.

Mahmud al-Wasiti, Baghdad, 1237 CE

The status of these intellectuals came from their access to embodied and institutionalized cultural capital i.e. bodies of knowledge and habits of mind acquired over time from experience and teachers. Intellectuals today still derive their status from various “houses of wisdom.” They grow up in the homes of scholars. They join academic clubs in school. They develop expertise in a privileged learned language. They join professional associations. They graduate from and teach at prestigious universities.

The rise of global capitalism, white supremacy, nation-states, and settler colonialism have radically transformed the political and cultural terrain that intellectuals now navigate. They have platforms that their medieval counterparts didn’t have. Today intellectuals can gather listeners and dissenters in global virtual marketplaces like Facebook and Youtube. They can employ their cultural capital in these spaces, then disassociate their “personal views” from the institutions from which their capital is derived. Some are part of institutions that are more devoted to public order than to justice for the most marginalized and, therefore, use their scholarship to maintain the status quo.

Paradoxically, modern intellectuals are not completely dissimilar from, but at the same time both freer and more restrained than their earlier, premodern counterparts. They have an unprecedented intellectual range of motion and yet their moves can be circumscribed by the institutions with which they are affiliated. This has produced an ethical dilemma of sorts. Intellectuals can either use their platform to critique civil society — including the institutions that fostered their professional growth, or they can toe the party line.

This leaves us with an important question to investigate: With the modern world in the state that it’s in, what should be the role of the public intellectual?

“Intellectuals can either use their platform to critique civil society — including the institutions that fostered their professional growth, or they can toe the party line. This leaves us with an important question to investigate: With the modern world in the state that it’s in, what should be the role of the public intellectual?”

Roots

Thirty years ago, on July 8, 1989, Kimberlé Crenshaw spearheaded the first Critical Race Theory (CRT) workshop in Madison, Wisconsin. There were twenty-three scholars present — three Japanese-American, one Mexican-American, and nineteen Black folks. There were fourteen women and nine men. Some were Buddhist, some were Christian. None were Muslim. Together they created an analytic framework inspired by a diverse cross-section of thinkers and activists from the radical Black intellectual tradition, among which were Muslim intellectuals.

In the 1970s these scholars were students and teachers in american law schools bearing witness to the failure of liberal civil rights ideology. They realized that liberal reform could never adequately address the centrality of race to the systems of law being challenged. In the same time frame , arguably the most prominent Muslim figure of the time in the U.S., the Honorable Elijah Muhammad, had reached the height of his national prestige. As leader of the Nation of Islam (NOI) — the largest Muslim organization in the West — he had established institutions and industries across the U.S. The organization boasted a printing plant, cold storage, restaurants, supermarkets, bakeries, schools, a trading partnership with Peru, and thousands of followers.

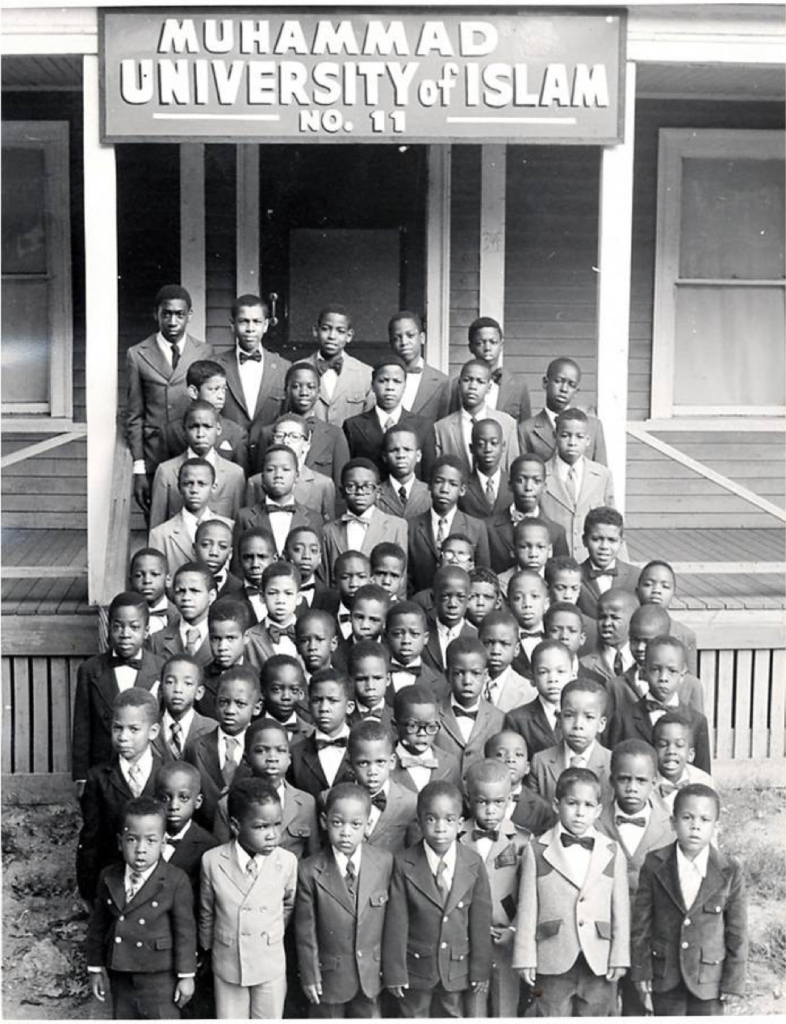

Elijah Muhammad wanted to demonstrate the possibilities of Black economic self-reliance. The goal, however, wasn’t simply Black-controlled institutions and industries. It was “full and complete freedom” from the idolatry that is white supremacy. In order to accomplish this, the NOI had to a) show an alternative to the racial economic, political, and social caste system of America and b) dispel the myths that bind us to the current system of white supremacist domination e.g. American meritocracy, exceptionalism and the black savage/white savior dichotomy. To this end, the NOI established its first institution in 1934 — the Muhammad University of Islam (MUI). Its purpose was to indoctrinate youth with a Black-affirming, humanizing Islamic curriculum. The later launch of the public education and recruitment campaign colloquially referred to in the NOI as “fishing for lost-founds” had the complementary goal of re-educating adults.

Though not usually remembered as an educator and intellectual, Elijah Muhammad’s blunt, interdisciplinary analysis of American society sparked a Black intellectual renaissance. Claude Clegg, author of An Original Man: The Life and Times of Elijah Muhammad, commented that “no other historical personality has had the kind of prolonged impact on black consciousness that he has had…” Like Elijah Muhammad‘s teachings, Critical Race Theory was designed to provide people of color with the language and tools to understand, critique, and resist white America’s historical dominance. Some historians and educators even argue that several of CRT’s core propositions were first articulated by Elijah Muhammad.

Critical Race Theory Propositions

-

Racism is an ordinary, endemic feature of American life

-

American law and society is not race-neutral, objective, or meritocratic

-

People of Color’s experiential knowledge represents a counter-narrative that is central to understanding and subverting racial inequalities

-

The dominant culture will tolerate and support advancements towards racial equality only when it suits its interests to do so

-

Race & racism must be placed in both contemporary and historical context using interdisciplinary methods

In his contribution to the 2016 anthology Africana Islamic Studies, Professor Jinaki Abdullah argues that Elijah Muhammad’s cosmology — as described in his book Message to the Blackman in America — constitutes a counter-narrative to the dominant narrative of white superiority. Through this cosmological counter-narrative, he exposes the illogic of white supremacy by inverting it. White people — not Black — were evil by nature. Their entire existence was dependent on the Blackman, maker, and owner of the earth itself. This was a reconstruction of Black identity as resistance against anti-black racist distortions of Black personhood.

Dr. Abul Pitre points out in his book, The Educational Philosophy of Elijah Muhammad: Education for a New World, that a parable within this cosmology teaches us CRT’s first proposition: racism is endemic in Western society. The story takes place thousands of years ago on a small Greek island on the Aegean Sea. A scientist named Yakub created a new, dystopian civilization through medical experimentation on dark bodies. The result was the development of a culture that glorified white people and violently subjugated and exterminated Black people. It was an ethno-state and every one of its institutions served to expand and maintain it. Over time, the island became dominated by this “new race” of people. To Elijah Muhammad, America was the dystopian island that Black people were all trapped in. To integrate then, would lead to a gradual, yet certain death.

It is for this reason the NOI excoriated integrationists at every turn — from clergy to activists to academics. They believed that Black leaders were failing in their responsibility to the people because instead of calling for an exodus from the land of bondage they were calling for assimilation into it. While Malcolm X was the national representative of the NOI he stylized the Black intelligentsia as well-dressed, well-educated apologists for white supremacy. These criticisms were part of a growing chorus of younger Black radical voices critiquing the role of public intellectuals and leaders in the Black community. While many mainstream civil rights leaders took action, few did so based on a critical analysis of race and racism in the U.S. Their strategies, therefore, couldn’t lead to the full and complete liberation because they didn’t account for the myriad ways in which Black people were unfree.

Source: https://www.claramuhammadfoundation.org/history-of-schools/

The rise of critical theorizing towards achieving Black freedom was influenced by the Black Islamic political and religious discourse of the time. The Black Panther Party for Self Defense modeled their ten-point plan on the Black Muslim creed. James H. Cone, hailed the father of Black Liberation theology, was heavily influenced by Malcolm X’s analysis of Eurocentric Christianity. Derrick Bell, one of the originators of CRT, echoed Elijah Muhammad’s sentiments concerning Black people’s political and social status in the U.S. saying that:

“Black people will never gain full equality in this country. Even those herculean efforts we hail as successful will produce no more than temporary “peaks of progress,” short-lived victories that slide into irrelevance as racial patterns adapt in ways that maintain white dominance. This is a hard-to-accept fact that all history verifies. We must acknowledge it, not as a sign of submission, but as an act of ultimate defiance.”[1]

The NOI created an entire class of lay intellectuals. They stood on soapboxes in the streets and behind pulpits in auditoriums using rhetoric, logic, and dialectic to deconstruct White Supremacy in a way the masses would understand. They argued that temporary solutions only benefited the few. They talked Black folks out of a politics of denial regarding our place in America. Convinced us to return to our roots. To accept our own and be ourselves.

“The NOI created an entire class of lay intellectuals. They stood on soapboxes in the streets and behind pulpits in auditoriums using rhetoric, logic, and dialectic to deconstruct White Supremacy in a way the masses would understand. They argued that temporary solutions only benefited the few. They talked Black folks out of a politics of denial regarding our place in America. Convinced us to return to our roots. To accept our own and be ourselves.”

Threshing

Ralph Waldo Emerson wrote that the American intellectual’s most important task is to take action — a corollary to the proposition of Imam Ghazali (may God ennoble his face), “knowledge without action is vanity.” A century and a half later, Edward Said asserted that the primary role of the public intellectual is to advance human freedom and knowledge by opposing systems of oppression. While I agree with both, citing these men does not constitute a wholesale endorsement of all of their ideas. For instance, I take issue with Emerson’s notion that the intellectual’s work is done out of obligation to himself. In the Qur’an, God instructs Prophet Abraham (peace be upon him) to tell his people that the first obligation of believers — be they intellectuals or not — is to God:

“Say: Verily my prayer and my worship, my life, and my death are for Allah, the Lord of the Worlds.” — Qur’an 6:162

I also do not agree with Said’s dichotomizing of the private and public life of an intellectual. Prophet Muhammad (peace be upon him) said that he has been commanded to “remain conscious of God whether in public or private.” That means there is no barrier between his private morality and convictions and his public speech and actions.

To separate the wheat from the chaff in the field of ideas has, arguably, always been an essential part of public intellectuals’ charge. For Muslims, it means offering a compelling argument based on the sources of our tradition for why this idea is wheat and why that idea is chaff. It’s becoming what Emerson called “Man thinking” rather than a “mere thinker.”

“Say [Prophet], ‘I advise you to do one thing only: stand before God, in pairs or singly, and think…” — Qur’an 34:46

A prerequisite to constructing an argument for or against an idea is inquiry-based questioning. It means asking the “right question”, one that invites us to think rather than cues us towards an answer. For example, instead of asking “how Islamic” something is we might ask what benefit can Muslims derive from this? or How might we apply what originates outside of our tradition in a way that maintains the integrity of our tradition? These questions keep us open-minded by ensuring we do not reach conclusions before a thorough analysis. Otherwise, our inquiry isn’t that at all. It’s just hot air.

Lives and Matter

Critical race theorists can be divided into two camps: idealists and realists. Realists rely on philosophical monism to interpret the choices and motivations of the dominant culture as it relates to racial oppression. They argue that white America only supports racial equality when it suits their material interests. In other words, white racism is determined only by material factors, a belief owed to its neo-Marxist roots. What this analysis leaves out is any spiritual impetus for changes in the material world. While material factors do help us better understand human behaviors, they are limited in what they can explain about reality.

“Say: O Allah! Creator of the heavens and the earth! Knower of the unseen (al-ghaib) and the visible (al-shahada)! Thou that wilt judge between Thy Servants in those matters about which they have differed.” — Qur’an 39:46

Here, the Qur’an describes a dual reality using the semantic pair al-ghaib wa al-shahada. In English, it means “all that is beyond the reach of a created being’s perception [as well as] all that can be witnessed by a creature’s senses or mind.” The ghaib is the side of reality beyond the visible one. American Muslim scholar Dr. Umar Faruq Abd-Allah elaborates about this hidden reality:

“Because of its semantic background, al-ghaib in its Qur’anic context refers to all things that stand without human perception — whether they stand outside of it by virtue of their nonmaterial nature as in the case of God and the angels or whether they have not been perceived or have not been retained in perception — as, for example, future events, forgotten things, or things of any period which are material but unknowable…The word, therefore, does not denote only supernatural realities.”[2]

“Critical race theory represents a lens through which we can discern the ‘invisible’ mechanisms of power and control that underlie the modern world.”

Critical race theory represents a lens through which we can discern the “invisible” mechanisms of power and control that underlie the modern world. But the ghaib cannot be reduced simply to systems of oppression that, by virtue of their abstraction and our entanglement in them, eludes our perception. There is a side of reality known only by God and those whom God has inspired. It is nonmaterial yet impacts the affairs of the material world. Therefore, to relegate human affairs strictly to what can be seen is a denial of half of reality.

Praxis Makes Perfect

One of the best ways to illustrate CRT’s benefits is to apply its tenets in analyzing a problem.

Problem:

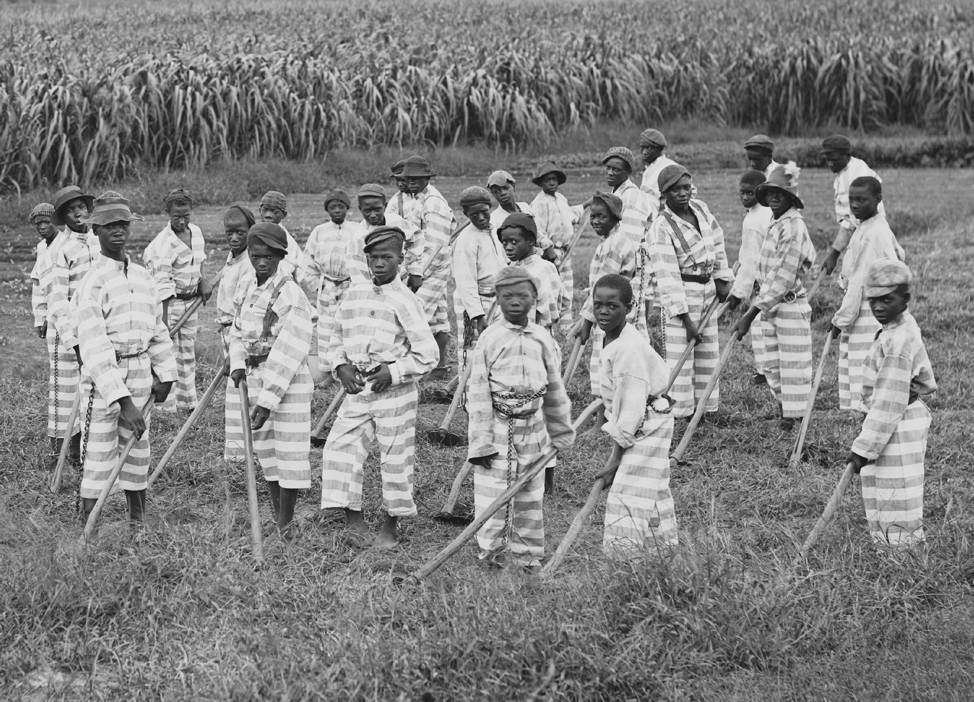

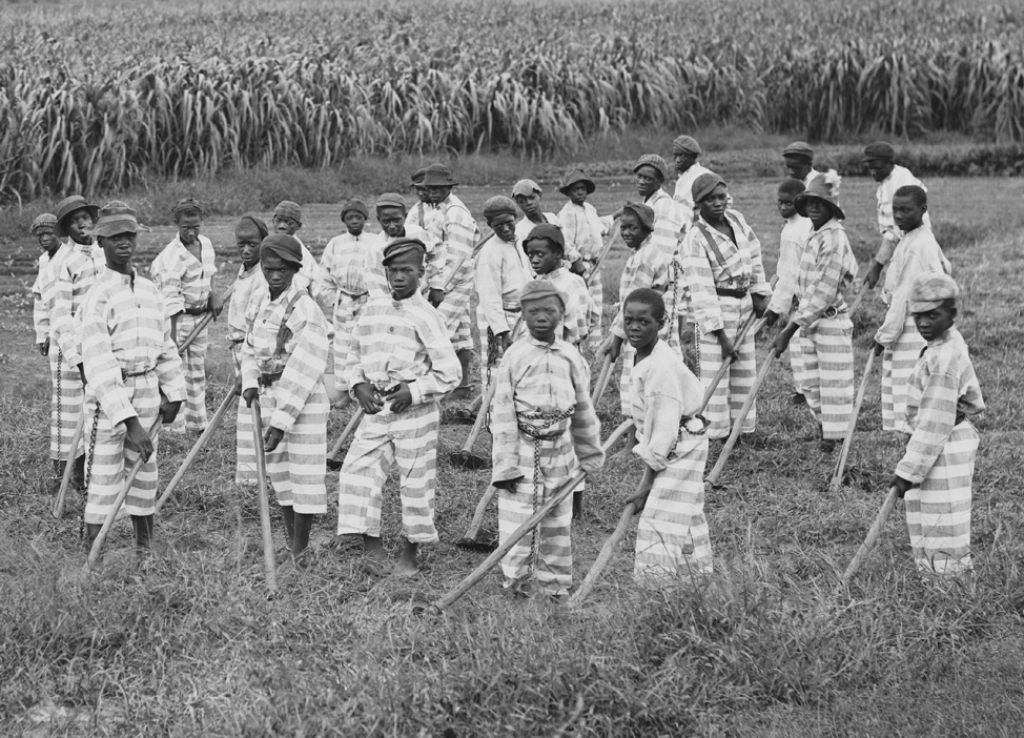

Black men are six times as likely to be incarcerated as white men.

Analysis:

On the eve of the Civil War, there were approximately four million Black people incarcerated on plantations across the south. This is the earliest example of disparities in incarceration rates in American history. During the antebellum period, Black people would be arrested for “crimes” like vagrancy, then fined, imprisoned, and “hired out” as unpaid laborers to white land and business owners. This evolved into the system of convict leasing creating economic incentives for the burgeoning prison industry to fill their beds with Black bodies. The end of Reconstruction was marked by the erosion of political rights and legal protections for Black people and the rise of Jim Crow. The confluence of all these social, political and economic factors created the context in which Black crime emerged in the U.S. In Trumpet of Conscience, Dr. King employs this kind of analysis in his commentary about a related issue — Black poverty:

“…The slums are the handiwork of a vicious system of the white society; Negroes live in them, but they do not make them, any more than a prisoner makes a prison.”

While drumming up support for the Poor People’s Campaign a year later, he had this to say about the difference between white and Black poverty:

“Through an act of Congress, our government was giving away millions of acres of land in the West and the Midwest, which meant that it was willing to undergird its White peasants from Europe with an economic floor. But not only did they give the land, they built land grant colleges with government money to teach them how to farm. Not only that, they provided county agents to further their expertise in farming. Not only that, they provided low-interest rates in order that they could mechanize their farms. Not only that, today many of these people are receiving millions of dollars in federal subsidies not to farm and they are the very people telling the Black man that he ought to lift himself by his own bootstraps. This is what we are faced with and this is a reality. Now, when we come to Washington in this campaign, we’re coming to get our check.”

Instead of moralizing and individualizing Black poverty, Dr. King contextualized it. He analyzed policies that create and maintain racial inequalities and demanded redress to bring about substantive equality. When we lack historical perspective and good theory we cannot offer these kinds of nuanced analyses or solutions. We can only offer superficial ones based largely on what we see in front of us. Black men commit crimes. They rob stores. They kill each other. The problem gets reduced to a single cause — poor choices. What we fail to see is the web of contentious behavioral contingencies deeply embedded in all social relations in the U.S. This isn’t an inherent blind spot though. The mind can be trained to see what is behind the veil. Absent this intellectual training, though, we give into the human impulse of arrogant denial. We deny what we cannot see and persist in our denial even after being shown.

“Those who behave arrogantly on the earth without a right — them will I turn away from My proofs: Even if they see all the signs, they will not believe in them…” — Qur’an 7:146

Black poverty, criminality, and criminalization are not phenomena that emerged in a vacuum. They are products of larger systems of exploitation that have always existed in this country in some form. The signs are all around us. We just have to learn to read them.

Epilogue

The economic, cultural, and scientific flourishing under the Abbasid Caliphate is called by some historians the “Islamic Golden Age.” It would not have been possible if Muslim intellectuals were not willing to study, critique, and build upon the inquiry, discoveries, and teachings of the Greeks, the Indians, the Chinese, and the Persians. They approached new ideas with a critical lens — that is, they investigated claims, identified useful knowledge, and built upon the scholarship of others. For example, Muslim philosopher, polymath, and alchemist Abu Bakr Muhammad ibn Zakariya al-Razi studied and developed the medical theory of Greek physician Galen. While he had high regard for his work, it didn’t prevent him from disagreeing with some of his ideas and even correcting them.

Critical Race Theory is far from the perfect guidance of the Book of Allah. But this is no argument for throwing it out completely — even if the one calling for its disposal knows Classical Arabic and has an ijaza. Nirvana fallacies and appeals to authority reveal how little investigation some Muslims scholars and their followers have done in order to understand CRT’s central ideas. Nonetheless, things can be imperfect and still have merit. From ideas to people, there is value in the problematic. This includes CRT and critiques of it — even the ill-conceived ones.

Using an interdisciplinary, critical lens to analyze today’s problems is something Muslim intellectuals aren’t typically given license to do. After Tariq Ramadan published his book, The Quest for Meaning: Developing a Philosophy of Pluralism, a French journalist asked him if he was still a believer. Ramadan comments on this in an essay published in the Guardian:

“He seemed unable to imagine that a believing Muslim could be open to other horizons: looking through his own window he had confined the “Muslim intellectual” into what he saw as the obligatory frame, with its cut-and-dried certainties that a priori rejected rational criticism and could thus only be imposed on others.”

Muslim intellectuals, Ramadan[3] says, are not confined to “only speak of Islam or hold his piece [sic]” However, when they do offer commentary about issues outside of their training, they must not only be open to other horizons but actually explore them. That means reading past the introduction of an “Intro to…” book. It means reading essays and academic journals written by scholars in the discipline. It means publishing well-documented analyses and critiques with logical arguments and counter-arguments. It means doing the work of, well, a public intellectual.

[1] Derrick Bell, Racial Realism, 24 CONN. L REv. 363 (1992), 373.

[2] Umar F. Abd-Allah, “The Perceptible and the Unseen: The Qur’anic Conception of Man’s Relationship to God and Realities Beyond Human Perception,” in Mormons and Muslims: Spiritual Foundations and Modern Manifestations, ed. Spencer J. Palmer (Provo, UT: Religious Studies Center, Brigham Young University 2002), 209–64.

[3] Author and Editors’ Note: We know that accusations of abuse have been made against Ramadan and understand that mentioning him may be triggering for survivors. We both stand with survivors of assault and believe that Ramadan’s insight here continues to be relevant and meaningful for the purposes of this conversation.