Namık Sinan Turan- Dear Bilen, you are known as the most important authority on Şerif Muhiddin Targan in Turkey today due to your musical performance and academic research on the oud. Before talking about your works, can you tell us a little about yourself?

Bilen Işıktaş- Thank you for your very kind words but I am just trying to do my work on this path with dedication. I was born in Istanbul in 1980. I completed my primary and middle school education in Istanbul. In 2003 I was accepted into the Basic Sciences and Voice Training Departments of the Turkish Music State Conservatory at Istanbul Technical University (ITU). While studying at the university, I went in search of both trying to improve myself as a performer and discovering the legacy of the great masters who had served before us. During those years I was interested in reading and research. Yet music has always been at the center of my life. With Bekir Şahin Baloğlu and Dr. Sami Dural, we formed the 3Dem Oud Trio. We released the album “Geç” [Late], which consists of a repertoire of musical instruments. In 2008, I started my master’s program on Turkish Music at ITU’s Social Sciences Institute. I graduated in 2011 with my thesis Şerif Muhidin Targan’s Contribution to Oud Techniques: An Analysis of the 6 Oud Taksims [Improvisations]. In June 2009, I placed second in the world in the international oud competition organized by the Arab Music Academy and the Holy Spirit University of Kaslik (USEK) located in Beirut. I never left my relationship with Targan at the academic level. I completed my doctorate in 2016 with my doctoral dissertation titled The Relationship between Modernization, Individualization, and Virtuosity in the Transition Period from the Ottoman Empire to the Republic: Şerif Muhiddin Targan.

NST- In the meantime you also carried out both artistic activities and academic studies at the same time. Balancing both must be difficult; can you briefly talk about how you managed it?

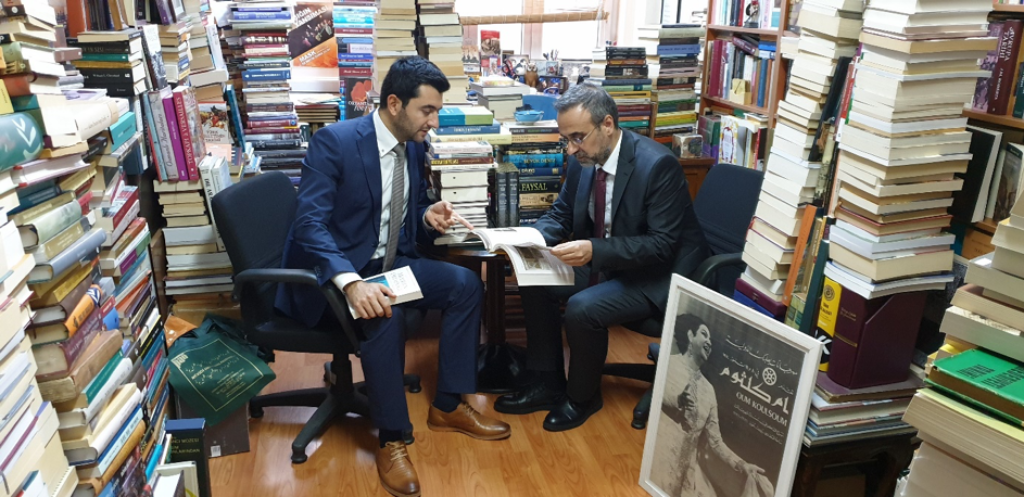

BI- Of course there are difficult aspects, but if you do a job with love and passion, you can overcome such difficulties. Yes, I have taken part in major artistic events with my oud in many places of the world. I have given concerts in many countries such as Belgium, England, France, Holland, Germany, Italy, Macedonia, the United Arab Emirates, Chile, Indonesia, South Korea and Malaysia. This allowed me to gain completely new experiences. In addition to my artistic studies, I have continued my academic activities without interruption. I have participated in many international symposiums in Turkey and abroad with my papers, book chapters, and articles. I can say that my academic studies have focused on topics such as sociology of music, historical musicology, Ottoman/Turkish music, the effect of modernization on music culture, the Frankfurt School, and popular culture. Every source and viewpoint that can nourish these fields is a point of interest for me. Thus, the writings of great master historians like Halil İnalcık and Fuat Köprülü as well as the works of great authorities on the history of Islamic sciences and Ottoman history have also been able to interest me. Furthermore, my studies titled Şerif Muhiddin Targan: As the Actor and Indicator of Modern Compounds, Introduction to the Innovative Nature of Şerif Muhiddin Targan’s Music, and The Impact of Recording Technology on Art and Mass Culture: Tanburi Cemil Bey have taken place in various international scientific media. My first book, Harflerin ve Seslerin Ruhundaki Seyyahlar: Mehmet Âkif Ersoy ve Şerif Muhiddin Targan [Travellers in the Soul of Letters and Sounds: Mehmet Akif Ersoy and Şerif Muhiddin Targan], which was released in 2017, was followed by my book Peygamber’in Dâhi Torunu: Şerif Muhiddin Targan, Modernleşme, Bireyselleşme, Virtüozite [The Prodigious Descendant of the Prophet: Şerif Muhiddin Targan, Modernization, Individualization, Virtuosity], which was published in late 2018. I work as a musicologist Assoc. Prof. Dr. in the State Conservatory Musicology Department of Istanbul University. Many of my works are available here for interested readers.

NST- Can you talk about coming second in the world at the international oud contest that took place in Beirut in 2009 and the repertoire you played there?

BI- Actually the main topic here is Şerif Muhiddin Targan, commonly known as Şerif Muhiddin Haydar in the Arab world. But let me summarize Beirut in a few sentences. It was a very exciting experience. Even if I hadn’t competed with good performers from Iraq, Egypt, Syria, and Lebanon, having cultural interactions with them was the most inspiring part of following their qualities of pitch, style, and tone. I made taksims [improvisations] by recording Şerif Muhiddin Targan’s “Caprice,” Cinuçen Tanrıkorur’s “Nihavent Saz Semai (Mehtapta Yakamozlar)” and various works from the repertoire of Arabic music. Truly it gave me pride to observe Şerif Muhiddin’s legacy everywhere.

NST- Your last book created an an overwhelming response, and you got reviews full of praise from the press and social media. You were found worthy of the best biography award for 2018 by the Writers Union of Turkey [Türkiye Yazarlar Birliği]. So, how did your path intersect with the art of Şerif Muhiddin, who is at the center of all these activities? What was in Şerif Muhiddin that influenced you?

BI- I should start with expressing my deep gratitude to Fahri Aral, the editor-in-chief of Istanbul Bilgi University Press, as well as to Beyza Becerikli and Cem Tuzun, for their invaluable help during the publication process. I started to build an interest on Şerif Muhiddin at the moment my path intersected with the oud. Certainly, his works influenced me like every oud player. We absolutely encounter with Şerif Muhiddin’s products when preparing a special oud repertoire. It is not enough just to see him as the first representative of autonomous legend. You also see that he was raised on the aesthetic musical vessels that captured the era. Some phrases that I can traditionally call themes and motifs in the works in which the music of our instruments compose the final instrumental section of classical Turkish music, play a big role in determining which sources will be benefited from. I had the chance to examine and analyze his taksims [improvisations], which helped me benefit from his mastery.

NST- You draw upon Şerif Muhiddin’s framework while discussing it in relationship to the concept of modernization theory. Can you explain this a little more?

BI- Modernization theory within the historical context provides guidance for the course of conceptual and theoretical approaches in our day and in various disciplines. The structure and basis of the beginning of the early modern era (i.e., industrial society) certainly differs from the cultural climate we find ourselves in. Yet the noteworthy point in our questioning is that we should consider the philosophical expansions reflecting the essence of the classical period in sociology, which includes evolutionist, progressive, positivist, and Eurocentric codes. Although development and modernization are sometimes used synonymously, the first of the main differences points to economic growth, and the second points to the various socio-cultural processes emerging with economic development. Social transformation creates axes of discussion turned to perceiving modern concepts related to specific topics such as forms of changing solidarity, urban life, fashion, rationalization, and standardization. This historical adventure finds new subjects for itself in music, in different cultures, and in social structures by departing from the theoretical groundwork. The distinguishing quality of modern society is that it gives individual roles to its members. This distribution of roles that confronts us with an action that is repeated every day is not a one-time deal. Therefore, Şerif Muhiddin, who turned a new page in our thoughts through the process of individualization, was found searching to load new meaning to the life principles of progress and development through a self-governing role, idea and freedom of self-expression that is self-determined. In this context, individualization is the process of transforming the things one possesses in one’s identity from birth into a task. Naturally, fulfilling this duty will place the responsibility of coping with it and its results on one’s own shoulders.

NST- In short, are we able to define this skillful performer and the cultural environment in which he was born? Being “şerif,” isn’t related to be affiliated with a noble genealogy?

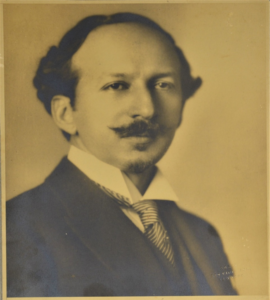

BI- This historical citation, which relates to Şerif Muhiddin being associated with noble roots as a thirty-seventh generation descendant of Prophet Muhammad, is extremely meaningful in terms of determining his inaccessible position within our observed history. Şerif Muhiddin’s father was Şerif Ali Haydar Pasha, son of Ali Cabir Pasha and the grandson of Abdulmuttalib bin Galib, the last Emir of Mecca; he was born in Kanlıca in Istanbul in April 1866 in his grandfather’s mansion. Ali Haydar married Sabiha Hanım in the following years. Sabiha Hanım was the daughter of Tevhide Hanım and Ziver Efendi, the brother of Arif Mehmet Efendi, who had many governmental duties such as the Tophane Directorate, the Undersecretary of Hassa and Seraskerat (Ministry of Defense), the Grand National Assembly (Supreme Court), and the Vienna Embassy. Ali Haydar’s first child Abdülmecid was born during the fifth year of his marriage, and Muhiddin was born one year later. Other children’s names are Şerif Muhammad Emin and Şerif Faysal.

Şerif Muhiddin, born in Istanbul in 1892, undertook a new mission in the oud to which he had connected with great passion since an early age; he opened an entirely new era with the oud just like tanbur player Cemil Bey (1871-1916) did with the tanbur. In a form similar to the voice of Munir Nurettin and the compositions of Refik Fersan, Şerif Muhiddin was one of Cemil Bey’s cultural heirs. His ability to possess the title of virtuoso successor to Cemil Bey the tanbur player, rested in his instrument playing, which differed him from other names. Undoubtedly, the opportunities that were available to Şerif Muhiddin contributed to his social and economic status provided by the aristocratic environment he was located in. He raised himself as an artist receiving a good education and as a cultural person at the same time. In addition to the Near-East languages such as Arabic and Persian that arose in classical culture, he also learned French and English, which opened to him the doors of the Western culture, literature, and art. Attending the faculty of law, he also studied at the faculty of literature at the same time, which would nurture his intellectual knowledge. In five years, he graduated from both faculties. His wife, Safiye Ayla, wrote in her memoirs that the great poet Yahya Kemal (Turkish poet and writer), had benefitted from Şerif on the topic of ancient Arabic poetry and English literature by visiting his home. This shows how much he dominated the aesthetic elements and transitive nature between two distinct cultural worlds.

“His wife, Safiye Ayla, wrote in her memoirs that the great poet Yahya Kemal (Turkish poet and writer), had benefitted from Şerif on the topic of ancient Arabic poetry and English literature by visiting his home.”

Conversational meetings that brought intellectuals together began to become widespread in Turkey in the late nineteenth century. These meetings were adaptations to modern times of the parliamentary culture of Ottoman graces. Intellectual enlightenment was reflected in the in-house parlors at those meetings, where domestic and foreign artist men and women, would come together; the boundaries of cultural areas expanded. These locales had the quality of a new continent of culture. Şerif Ali Haydar Pasha’s pavilion in Çamlıca was also like this. This locale became a medium where Ismail Hakkı Izmirli, Mehmet Akif (Turkish poet), and violin virtuoso Charles Berger, in short those showing mastery in poetry, work, and sound, would share aesthetic experience. Founder of modern sociology, sociologist and thinker Georg Simmel’s house also witnessed an intellectual environment like this in Germany during the same period. Simmel came together with major writers, thinkers, and artists such as Stefan George, Raina Maria Rilke, Auguste Rodin, Edmund Husserl, and Max and Marianne Weber. The common thing was the coexistence of the demand for developing artistic and culturally aware networks. In short, intellectuals and artists in the East and the West shared their artistic and cultural productions again with those breathing the same air with them. Şerif Muhiddin was born into such a cultural circle.

NST- I suppose that Akif had a very special place in the life of Şerif Muhiddin.

BI- That is also a deep conversation. Akif had love and respect toward all members of Şerif’s family. The one who first brought Akif and Targan together was Ismail Hakkı Izmirli. Izmirli gave private lessons to Şerif Ali Haydar Pasha’s sons, Muhiddin and Abdülmecid at the mansion in Çamlıca. When Ali Haydar Pasha desired to meet, though exactly when is not known, Akif went at once to the mansion at the side of the master. There he saw Targan’s oud, and thus the first steps of a life-long friendship were taken. This friendship would show itself even at the most critical moments in the following years. For example, towards the end of the World War I, Izmirli and Akif went to Lebanon at the invitation of Ali Haydar Pasha, and they stayed there for a month or so. According to him, Şerif Muhiddin’s father, Şerif Ali Haydar Pasha, had the Prophet in his luminous countenance. Akif showed his respect and devotion to Ali Haydar Pasha by dedicating his poem “From the Deserts of Najid to Medina” to him. In the meantime, a solid friendship was established at the meetings in Çamlıca between Şerif Muhiddin and Akif. Poetry, music, literature, and sometimes politics brought people from different worlds together in this house. One should not forget that Gölgeler [Shadows], the seventh book from the compilation of Safahat written by Akif, is dedicated to the great artist Şerif Muhiddin.

According to one review, “Shadows” are poems that peer at the beyond anymore. Poems such as Hicran [bitterness of heart], Gece [Night], and Secde [Prostration] are the waves where the poet desires to attempt to forget himself in eternity and to bring harmony that consoles the self upon returning.” I also composed a music piece called Gölgeler, which I tried to describe their close friendship between them with sounds.

NST- That is a very original portrait within the last era of Ottoman intellectuals, can you expand a little more on this issue, noting the environment in which he was raised?

BI- The social environment where Şerif Muhiddin grew up was not able to become very distinguished when considering the high class, he at first belonged to. Views can be encountered of the type we see around the home of many elites. However, having a noble genealogy had given him an outstanding position in society since his birth. Even looking at the environment in Çamlıca where he grew up is highly instructive for the sake of understanding the cultural atmosphere that had shaped his childhood and personality. In this atmosphere, there were pianists such as Leopold Godowsky and Udi Ali Rifat Çağatay; important names in Turkish music history and theory such as Rauf Yekta (musicologist), Zekaizade Hafız Ahmet, Mehmed Akif; and master of the pen, the philosopher and religious scholar Ismail Hakkı. Şerif Muhiddin knew Tanburi Cemil Bey not from a concert hall in Pera or from a chapter in Direklerarası; Muhiddin knew him from his child years in the greeting area of the mansion as a noble guest in front of the community. He played the cello for him. Imagine Şerif Muhiddin learning English at the age of six from Indian Ali Asgar Efendi. He could read poems, literary, and philosophical texts in many languages. In fact, the entire family was like him; sisters (Şerife Nimet, Şerife Süfeyne and Şerife Misbah), brothers, all well-raised individuals who were intellectuals with high culture. More than just a musician, the legacy of the prominent intellectual of the period, is housed at the Süleymaniye Yazma Eser Kütüphanesi [Süleymaniye Manuscript Library].

NST- His achievements in New York and the reception he had are spectacular and yet we don’t know about it so much. So, how did you access these resources? What excited you most during your research in New York in 2015?

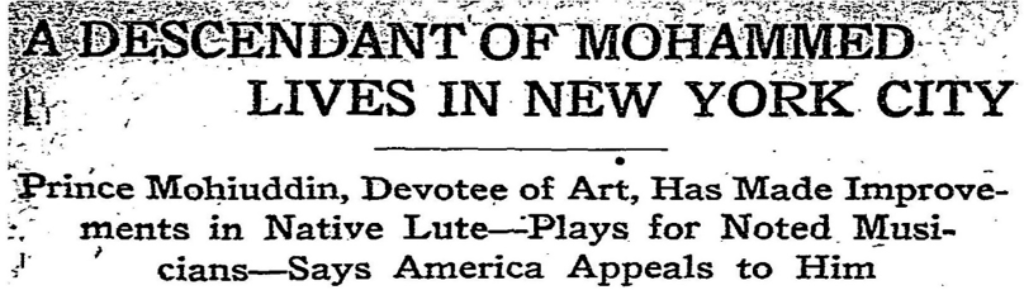

BI- What was really exciting was visiting the Town Hall stage where he gave concerts in 1928-1929, tracking him down in the archives there, and coming across his name at events I had never known while scanning the news of the period. The Town Hall concerts particularly made him a true virtuoso in the American music scene, as they called him “The Paganini of the Oud.” Among his friends in the city, aside from Leopold Godowsky, were also individuals like Fritz Kreisler, Mischa Elman, and Jascha Heifetz, who have been cited among the greatest violin virtuosos of all time. He was even together with the great scientist Albert Einstein at various social events. Individuals like Andres Segovia, George Enescu, Josef Hofmann, and Shura Cherkassky, who made impressions also in the twentieth century through their musical performances, were artists with whom his path intersected in New York. Let’s note that news was made on The New York Times with the headline “A descendant of Mohammed lives in New York City” in August 24, 1924, the third year of his arrival in the United States. In the years that followed, he was also placed on prominent newspapers through his achievements.

I discovered that he bore a spirit of solidarity towards other Eastern intellectuals and refugees in New York, such that his name could be encountered at every event organized for the needs of those who had come from Eastern countries. Interestingly, he did not get many heartfelt reactions during this period. We know that at the beginning of 1925, even though he had recorded with many famous record companies like Alexander Maloof, Columbia, and Victor, he still experienced financial troubles. How he showed his willpower to be able to struggle with those conditions is admirable for a person who had grown up under extremely good conditions. All this meant meeting with him somehow, touching the legacy that Targan had left while searching for his traces. I must mention the valuable contributions from the oud artist and composer Ara Dinkjian, who lives in New York. He opened the door for me to album recordings we had never heard before. He showed how misleading the stereotypical narrative is, in the way that Şerif Muhiddin, who nowadays is practically mythicized, had struck nothing apart from his own works. In the meantime, I can’t go on without saying this. After giving his great concerts in America, Şerif Muhiddin sent Mehmed Akif a telegram from Egypt. Its conclusion was important for Akif, because the concerts, apart from the musical performances, contained a different meaning: Two worlds had met on the same stage between the Orient and the West. That continued in books. Thinking about these topics also makes me excited.

NST- We are talking about a scholarly, multicultural mind very open to the world. Traces of this are clearly seen in all his works. Aside from having deep knowledge of traditional music, he also knew Western European music very well and was a virtuoso performer on the cello. Do you think this had any effect on his oud performance? This case is very noteworthy for me.

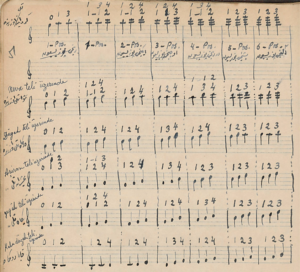

BI- Safiye Ayla stated that her husband, Şerif Muhiddin, had been influenced by Bach, Chopin, Paganini, and Liszt. This is true; traces from the geniuses of European classical music can be felt particularly in his etudes and tonal works. His dominance in cello compositions of course also provided the technical infrastructure of the reformation he made on his technical mastery of the oud. Because his finger adaptations were inspired by this instrument, we understand from the notes dropping over notes that it mirrors the oud. In particular, the wide spacing between his first and second fingers reveals that he was following a path apart from the classical training and performance methods.

NST- You’ve conducted interviews in your book with talented names from a quite wide circle, from Professor Jim Samson, an important name in musicology, to Idil Biret, our talented, world-renowned pianist, to today’s major performers of Turkish music. What common point do these names have in the context of Şerif Muhiddin?

BI- The common issue that attracts all their attention and with which I fully agree is that Şerif Muhiddin is a great artist, which fulfills the conditions of his virtuosity. In my study, I tried to identify this originality of his within Turkish music based on the inspired, historical, sociological, and musicological data that they also gave.

NST- What is the source of Şerif Muhiddin’s originality?

BI- For the oud, Şerif Muhiddin made sense of the new formats of a unique world in the limits of civilization and revealed this with a modern tone. The historian, Ilan Pappé, wrote a section titled “The Modern History of the Ud” in his book The Modern Middle East. We don’t encounter with the name of Şerif Muhiddin there, the careers of mostly Egyptian and Syrian oud players are discussed. However, one must admit that the profound actor who gave direction to the oud’s modern history was certainly Şerif Muhiddin Targan. In short, he was the milestone of a new era in the oud. The modernization process is found to reflect not just in the social environment, but also in the human mind. He chose sources of attribution that would nourish art and placed his performance between a framework oriented toward the new and the future through the sounds of time. In one context, we can say the characteristics of his unique style proceeded to the future in the perspective of innovation. The works of this genius who lived in the golden age of the oud reveals his performance through harmonizing the new sounds of the century with the past.

NST- Can you provide information about his place among the talented musical instrument performers in Turkish music?

BI- The oud player, Nevres Bey, who is accepted as a distinct turning point in oud performance in Ottoman/Turkish music and performed together with the tanbur player Cemil Bey, is found to have commented, “His miracle is the oud in his hands, he is untouchable,” while talking about Şerif Muhiddin. We should note that Nevres Bey was one of the teachers of the esteemed artist Safiye Ayla who in later years would unite her life with Şerif Muhiddin on April 8, 1950 and he said these words at a council where Lady Safiye was also present. These words are not an unnecessary award or an exaggerated analogy, they are a reference made with elegant and chivalrous thought to Şerif Muhiddin’s family roots. Within the long historical tradition of Islam and as a miracle of the esteemed Prophet, the Quran is shown to be the last book possessing the quality to be able to give an answer to every century. Thus, the miracle of Şerif Muhiddin, as an innovator who guided the oud’s development with a virtuosity that came to the world as a member of the Prophet’s family, is his superior performance on the oud. the quote above from the oud player Nevres Bey about Serif Muhiddin, then is an expression of his view toward Şerif within the generation of performers who would come later after him. Mentioning Şerif, another musical genius, Mesud Cemil described him as “an artist who seamlessly and effortlessly combined the oud with cello and the East with the West on the same stage.” The oud masters of the following era also accepted Şerif Muhiddin as an authority on oud performance. All over the East, Şerif Muhiddin is the Lord of the oud, the King of the oud.

NST- How can virtuosity be described, particularly, what is outstanding about the virtuosity of Şerif Muhiddin’s?

BI- Virtuosity is a special case where music is individualized in terms of the performer reinterpreting it in spite of the music itself. The performer makes references to lost traditions and bravely shows the quest for originality that will reveal the performer’s own desires from within. Şerif Muhiddin, who separated himself from the tradition that was re-poured in a mold as the musical doxa* of the twentieth century, dismantled things with the purpose of putting them back in their place. He sensed the differences within consecutive generations and revealed them rationally, predictably, and confidently with specific goals. The steps of originality and individualization proceeded outside of traditional venues, times, environments, and styles. The demand to change playing techniques would transform the ways in which emotion was projected by acquainting with the new and making it resemble the old. When we come to his performance, internal processes verbalized the dynamic qualities of the world of auditory experiences such as crescendo & diminuendo and accelerando & ritardando through the intensity of the sound in the music at a directly observable event and in his improvisations, which had the rarest colors of a painting knitted with sounds. Increasing the internal tempo and finding response in the movement thus diversifies and varies the output. Can the historical, social, and economic conditions that create musicality be discussed independent from the musician’s music? Obviously, this question is not too easy to answer. Maybe musicians can be born beyond an era and customize their own conditions despite deficiencies. The constructive materials of the language of music certainly testify to the sounds, but the performer forces the creative possibilities to the limit by also considering the contradictions and inconsistencies from place to place. The virtuoso is the one who not only develops the boundaries of performance and capacity of the oud, but also methodizes this and produces a new repertoire.

NST- If you talk about personality traits, what are Şerif Muhiddin’s most remarkable traits?

BI- Immediately after Şerif Muhiddin Targan’s death on September 13, 1967, Hilmi Rit (qanun player) described him with the following words that rang under the dome of the sky: “The loss of Şerif Muhiddin is not just a loss for the world of music, but also for the world of humanity. He was the epitome of dignity, politeness, grace, and humanity and a saintly master.” Both contemporary masters as well as literary masters indicated another point apart from his outstanding talent. He was a representative of a noble genealogy who never hurt or crushed anyone because his smile was never absent; it sprinkled colors from the heart. It was seen in the humanity, the art, and the harmonious integrity that it conveyed and supported each one aesthetically within the other. He reflected his accumulation into his works by looking through the horizon of affection from within a style of elegance. His mastery of the cello as well as his success over the line of being an artist brought his oud works to a product of different dynamics. As Taylan Altuğ stated in his book Son Bakışta Sanat [Art at a Last Glance], “He was a person within whom artistic creative subjectivity resided, and this subjectivity was seen as human not in his personal history but in his works.”

NST- Thanks to your work in the recent years, Şerif Muhiddin again on the agenda in Turkey. Nevertheless, what could have been the reason for him being ignored for many years in his own country? How do you interpret his having many more followers in the Arab world these days?

BI- I think the most significant factor is that he is not able to be understood enough through artistic circles, such that even today innumerable and unfair critiques can be made regarding his art and performance. His performance can be assessed as dull, emotionless and very technical. Criticisms can of course be directly about an artist’s performance. But those who do this must have the caliber and characteristics to be able to evaluate the art of Şerif Muhiddin. Otherwise, we can consider these criticisms as personal and non-academic comments. If I may put forth a second reason, Şerif Muhiddin’s presence in America, far from his country in the first years of the Republic when cultural policies were shaped in Turkey, may have weakened his connection with musical circles here. In fact, shortly after his return he went to Baghdad where he would remain for many years. Therefore, the process here is the last period of his career both as an instructor and a great artist.

“Şerif Muhiddin’s presence in America, far from his country in the first years of the Republic when cultural policies were shaped in Turkey, may have weakened his connection with musical circles here. In fact, shortly after his return he went to Baghdad where he would remain for many years.”

When he was in Iraq, he made great contributions to the country’s cultural life both as a teacher and a director through artistic activities. Talented students such as Selman Shukur and the brothers Munir and Jamil Bashir who he trained at the Baghdad Conservatory kept the school of teachers alive by later signing on to great jobs. Munir Bashir in particular would be applauded in the international arena as the most important representative of the Baghdad school of the oud. In short, his students were successful at transferring Targan’s legacy from generation to generation. In this respect, the two-volume oud method that Jamil Bashir prepared and dedicated to his teacher, Şerif Muhiddin, also was in fact an important step regarding systematizing his teacher’s oud technique. He wanted to benefıt from his master’s characteristic of high teaching in Turkey, but he could not perform what they wanted at the Scholarly Board Presidency of the Istanbul Municipal Conservatory where he was appointed in 1948. The cultural atmosphere of the period as well as health conditions that were the hindrances not allowing allow this.

NST- His years in Iraq were also noteworthy. We have yet to fully examine the impact of the late Ottoman period elites on the development of modern Arab countries’ political and cultural institutions. Only Sati al-Husri’s role in education has been emphasized. Meanwhile, you fill a big gap in particular by also discussing in detail his years in Iraq. Can you touch upon Şerif Muhiddin’s period in Iraq and the heritage he left there?

BI- The distinguished musicologist Ali Jihad Racy, in the introduction of his horizon-opening book Making Music in the Arab World, referred to the educational role given by Şerif Muhiddin, the great representative of Turkish music schools, as well as to the creativity of local Iraqi artists and the impact of Western-style musical education, on the development of the modern Iraq oud playing-style starting from the 1930s.The students he instructed here represented his school internationally. In my opinion, another aspect just as important is the undeniable contributions he made in the establishment of cultural and artistic institutions in modern Iraq. Imagine, the descendent of the Prophet is the founder of painting and sculpture sectors. He had a broad vision. He played a big role in the institutionalization and placement of not just the conservatory but also other fields of art. By inviting friends, he had been with since New York to Baghdad, he became one of the major architects enriching the cultural experience in this country that had just been born.

NST- When we consider Targan’s students, we understand that he had formed an oud school. What can you say about this school and its representatives?

BI- Targan had an undeniable impact behind the new base-style that rose from Iraq in the second half of the century opposite the dominance of the Egyptian style. As much as the creativity of local Iraqi artists and the increasing impact had a share on the development of modern Iraq since the 1930s, which the oud playing style shows, so too did the education Targan gave.

” Targan had an undeniable impact behind the new base-style that rose from Iraq in the second half of the century opposite the dominance of the Egyptian style. As much as the creativity of local Iraqi artists and the increasing impact had a share on the development of modern Iraq since the 1930s, which the oud playing style shows, so too did the education Targan gave.”

Apart from Munir Bashir (1930-1997) and Jamil Bashir (1921-1977), Selman Shukur (1921-2007) is named as one of Targan’s students at the Baghdad Conservatory. By synthesizing Targan’s style and the aesthetic understanding of their own musical tastes, they mediated the establishment of an original Iraqi style and of the modern Iraq oud school. In addition to this, Şerif Muhiddin’s students included names such as Nazik al-Malaika (1923-2007), who would be recognized as one of Iraq’s famous poets, and Ghanim Haddad (1925-2012); they were students of Targan who developed by watching his techniques. Jamil Bashir, who was born in Mosul in 1921, was one of the first students in 1936 at the conservatory that Şerif Muhiddin had established in Baghdad. While Jamil had also been taking lessons simultaneously from the great violin teacher, Sandu Albu (1897-1978), he showed great development in a short time on the oud. After graduating in 1943 from the oud department with high honors, he started teaching as a lecturer at the conservatory with an invitation from Targan. Targan’s schooling was clearly felt in Jamil’s style. He had developed the technique he learned from Targan by synthesizing it with the Arabic style. By taking advantage of the techniques he had received from his teacher, Jamil created a style that was clearly felt in his performances as well as in his compositions and improvisations based on Turkish modal compositions and the rhythms of Iraqi and Arabic music. Another big name in Iraq from the Targan school, was Munir Bashir, Jamil’s brother born in Mosul in 1930, who was introduced to the oud by his brother Jamil; afterwards he received six years of oud training and also two years of cello training at the conservatory. Munir Bashir, the most talented student to train under Şerif Muhiddin, would become involved in Iraq’s art academies as a professor by serving as lecturer in the oud department from which he had graduated in 1945. As Targan’s influence was clearly felt in Munir Bashir’s style the institutions he was associated with due to his powerful art contributed to this school’s development.

NST- Where is Şerif Muhiddin’s musical heritage located within the repertoire of Turk music these days? Have his works been able to be introduced adequately and presented to audiences? How is a world-renowned virtuoso understood in his own country’s musical circles?

BI- I wish I could answer such a question without hesitation, but it’s such a shame that we have not yet been completely able to comprehend the importance and legacy of this great artist. In fact, we are quite removed from such a process. Of course, the interest this book has aroused has given me hope on this issue. His works are decisive at an indispensable technical level in instruction at conservatories. However, apart from a few of his instrumental pieces, we can’t say that his work has seen the interest that it deserves. As young performers, we strive to voice his works by introducing it from our hands when necessary. In this way we carry his legacy to the future. But please allow me to express that great artists in the Arab world these days like Umm Kulthum, Mohammed Abdel Wahab, Mohamed el-Qasabgi, Riad el-Sunbati, Wadih el-Safi, Asmahan, and Fairuz view their great reputations as a source of pride for their countries and communities. When it comes to Greece, Maria Callas comes to mind immediately, as does Frank Sinatra for America. For Iraq, the brothers Munir and Jamil Bashir are names still mentioned as cultural icons in every study. Authorities like Ilan Pappé dedicate separate sections to these names in the classicized works on the history of the Middle East. We should hold names like Şerif Muhiddin, Tanburi Cemil Bey, Tanburi Necdet Yaşar, and Neyzen Niyazi Sayın with great esteem and keep them alive as eternal lights of the country’s artistic heritage. As the young generation, we are engaged in this. We serve as best as possible. Involvement in music as the 3Dem Oud Trio and our academic presentations at the International Şerif Muhiddin Targan Oud Festival, which took place for the first time in Malaysia, have been very important for us. I hope these events will continue to increase in our country and in the international arena. Also, some previous studies done on Şerif Muhiddin have helped me to deepen the subject. In particular, names such as Prof. Dr. M. Hakan Cevher, Mehmet Güntekin, Nuri Özcan, Zeki Yılmaz, and Jean-Claude Chabrier are also found among those who have contributed to this subject.

NST- Şerif Muhiddin lived in an age that witnessed traumatic fractures between cultures and geographies. Since his father was the last Emir of Mecca, he witnessed the most turbulent period of the World War I in Medina in the lands of his ancestors. He also witnessed the sorrowful process of the Ottoman withdrawal from the Middle East. Can you tell us a little about that period and its impacts on his life?

“The transition of another branch of his family, namely his cousins to the heads of Jordan and Iraq with the support of the British, directly affected the destiny of Şerif Muhiddin’s family. First of all, they were punished for being loyal to the Ottoman administration and lost their wealth.”

BI- The transition of another branch of his family, namely his cousins to the heads of Jordan and Iraq with the support of the British, directly affected the destiny of Şerif Muhiddin’s family. First of all, they were punished for being loyal to the Ottoman administration and lost their wealth -cases concerning this matter in international courts would reach resolution only after Şerif Muhiddin’s death. A period of poverty followed his childhood after he had spent in mansions in Istanbul. The family had distributed the imperial balance across the land. The Ottoman Empire’s last Şerif of Mecca died in 1935 in Beirut under extremely difficult conditions. Şerif Muhiddin was also under extraordinary conditions, going to the lands that had belonged to his ancestors in his youth. When I accessed photos from that period, I experienced great excitement. Sometimes here he would come across with me while inspecting Fahreddin Pasha’s military units, namely at the head, sometimes at various social events in Medina with family members, planting palm seedlings for example. If we had had a diary from those days, who knows what it would have told. Unfortunately, he did not keep a regular diary in Iraq; there are letters and correspondence with his friends. Some of these are in my personal archive. Şerif Muhiddin left his signature through his art and identity of instructor at a time when the modern Middle East was shaped.

NST- Şerif Muhiddin was a versatile artist. At the same time, he was a painter. From which sources did all this accumulation and artistic production feed?

BI- An artist can be inspired from many sources. In one interview, his wife Safiye Ayla said that Şerif Muhiddin was bound with love and passion to everything that is beautiful. In fact, this point is common to all artists; they seek all that is beautiful and aesthetic. Sometimes with a plectrum, sometimes with the bow, sometimes with the colors reflected from the palette with his brush, he discovered and shared what was beautiful. We are talking about a person who, even during recovery from surgery in a hospital in New York, drew with black pen the portrait of the caregiver who took care of him and made a portrait of the doctor. That is to say, every condition and agenda can also be a source of inspiration.

NST- Lastly, what can you say for an artist and intellectual such as Şerif Muhiddin? What kind of place will he have in your studies after this?

BI- Explaining him in a single sentence is not easy for me at all. I continue to find something new about him every day. He has a very significant place in my life, and has been my most important source of inspiration in shaping both my artistic and academic identity. Clearly, for me, he is a portrait transcending the ages through art. He was a man who devoted his entire life to art; he had such a deep sense of devotion to art that nothing he did satisfied him. He expressed that with great humility. We deal with a great artist in the true sense. Rollo May, in his seminal study titled The Man Who Looked for Himself, had important explanations for great artists living at the end of the nineteenth century and early twentieth century: “Each contribution which was made led to the realization of the most significant developments that had come in their own fields. But these were in a way not the first big steps of their new age but the last big steps of the old age, right? After all, they were committed to the values and goals of the last 300 years; they were struggling to reach the goals of the age they were in, no matter how important or permanent the new methods they developed were. They lived before the age of emptiness.” Whenever I read these lines, I always remember Feyhaman Duran’s wonderful portrait of Şerif Muhiddin; probably the most beautiful abstract to explain him and secrets of his life hidden in these lines. Just as is in other great artists.

NST- Dear Bilen, thank you for this enjoyable and fulfilling conversation. I hope that this book, which is filled with valuable information on Targan’s life as well as photographs and information that we’ve seen for the first time, contributed to a greater appreciation for his art and his role in modern music. I hope one day this precious book also reaches readers in English and Arabic and Şerif Muhiddin is also studied in these languages.

BI- God willing. I am also thankful to you for giving me this opportunity to be able to tell the world about Şerif Muhiddin.

Namik Sinan Turan was born in Tarabya, Istanbul in 1972. His entire life of learning happened in Istanbul. After studying Political Science and International Relations at Istanbul University, he completed the work for his master’s degree in 1998 in the same division’s Political History Department. Afterwards, he gave a doctoral dissertation in 2003 entitled Structural Change in the Caliphate and the Ottomans. His studies focus on the much later Ottoman period and the social and political history of the Second Constitutional Period. His work areas include Ottoman diplomacy, political thought, and culture. His latest book, The Caliphate: From the History of Early Islam to the Last Century of the Ottoman Empire, was published by Istanbul Bilgi University publications in May 2017. He is currently a faculty member in the Department of Political Science and International Relations at Istanbul University’s Faculty of Economics.

* Common beliefs