Egypt’s Podcasts and Booktubes: A Literary Criticism of the Future? | by M Lynx Qualey

Cairo Since 1900: Book Review and Interview with the Author | by Shaimaa S. Ashour

Art as Education: Street Art as a Precursor to Social Change | by Marwa Gadallah

Umm Kulthum Conquers all: Kawkab al-Sharq through Pop Art | by N. A. Mansour

Athar and the Boundless Multiplication of Relics | by Richard McGregor

The Price of Popularity | by Sally El Sabbahy

Introduction | by N.A.Mansour

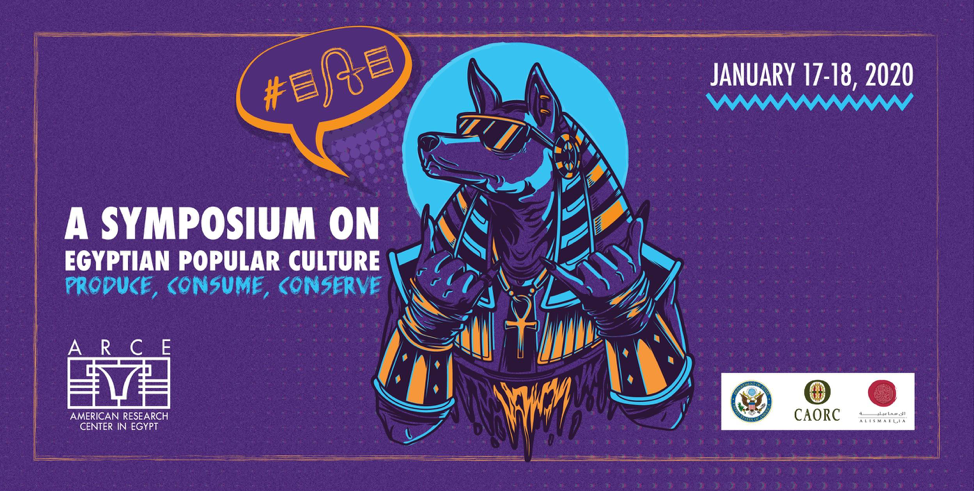

Produce, Consume, Conserve: A Symposium on Egyptian Popular Culture began as a conversation in downtown Cairo at the American Research Center in Egypt (ARCE) between cultural heritage professionals and a historian about how we consume what we see when we walk around Cairo. The conversation carried on and we moved on to the problematics of presenting a city: is there something wrong with instagramming what we find charming about Cairo while cropping out the undesirable? What about enjoying the city and not being conscious of how and why we should conserve it? Then the wheels began turning: we posed the question of how that applies to books and film. We wondered why conversations like these don’t happen in more formalized settings and if in some disciplines, they don’t happen at all. So we wrote our fantasy list of who we would put in a room together if we could. We talked about how feasible such an event could be at ARCE’s Cairo location. Then we got to work: speaking to potential participants, thinking of different speaking formats, and all the other details that go into something like this. Like the event title. Produce, Consume, Conserve embodied what we wanted out of the event: to highlight how things are produced and consumed and think about how we conserve them, in whatever form that may be. We want to inspire people to conserve, but to do so responsibly.

Later came the visuals, such as the event poster. An updated Anubis drawn out in purple, gold and safflower blue, the ancient Egyptian god that looks like a jackal, it is intended to be tongue-in-cheek. There is a little bit of ARCE’s rich history in archaeological research referenced in the usage of the Anubis figure, but then there’s also the fact that pharaonic references have worked themselves into Egyptian architecture, letters, and television (see this for an interesting marriage between Egypt’s past and Oum Kulthoum). But then there’s the flipside: in some ways, the pharaonic past is not part of everyday Egyptian popular culture. Interpret the Anubis mascot for Produce Consume, Conserve as you will. I think he simply looks cool.

When we were dreaming up Produce, Consume, Conserve, we also wanted to draw in an audience that extended beyond those warm bodies we managed to draw together for the actual symposium; we wanted to cross boundaries and inspire conversations both on Egyptian popular culture itself and popular culture at large. Conversations are pleasant, but they need to have some form of export. For that reason, I present to you a digital leg of the symposium: Produce, Consume, Conserve: An Essay Roundtable on Egyptian Popular Culture, produced in collaboration with the Maydan. We’re trying to do the same thing we are doing with the symposium: striking a balance between studies of the production of popular culture, notes on how we consume popular culture, and suggestions on how we should conserve popular culture.

The roundtable begins with M Lynx Qualey. She questions what is literary criticism in Arabic in this day and age and opens our eyes to how podcasts and Booktube shape the interests of readers of Arabic literature. Shaimaa Ashour then highlights an important new publication, Cairo since 1900: An Architectural Guide, by Mohamed ElShahed; she weaves in an interview with the author himself, casting light onto the process by which such a comprehensive book was assembled. For our purposes, Ashour’s discussion of the text reminds us that architecture is consumed daily and questions how that should figure into our day-to-day lives. Marwa Gadallah then writes an accompaniment to the work of Bahia Shehab, an artist-activist-academic whose work on wall murals spans the world over. Gadallah gives us a peep into Shehab’s process and what conversations it can inspire. Then we have Ida Nitter’s contribution on Mawlid al-Nabi, the celebration of the Prophet’s birthday, one of Egypt’s most popular celebrations: she looks at the customs surrounding food and religious ceremony, as well as the history infecting it all. I have a less academic contribution: surveying a decade in pop art detailing Oum Kulthoum, Egypt’s most iconic voice. But part of the reason why we’re trying to bring people together at Produce, Consume, Conserve is to celebrate pop culture, not to demean it because it is popular but to take popular opinion as an arbiter of taste: Richard McGregor does that for us in this digital convening of PCC, with an essay on athar, prophetic relics, folded in to a heavy consideration of the lines between elite and popular culture.

We hope you enjoy this series of essays, which, we again, thank the Maydan for hosting and collaborating with us: we will be releasing them twice weekly for the next few weeks. If you’re in Cairo the weekend of January 17th and 18th, please join us at Produce, Consume, Conserve.

N.A. Mansour is a PhD candidate at Princeton University’s Department of Near Eastern Studies, where she is writing a dissertation on the transition between manuscript and print in Arabic-contexts. Her interests include Islamic studies, Arabic-language pop culture, and food.

Egypt’s Podcasts and Booktubes: A Literary Criticism of the Future? | by M Lynx Qualey

In Arabic as in English, the power of the Big Critic has waned. The mid-twentieth-century Golden Age of literary criticism, with its masterful literary tastemakers based in cities central to a publishing industry, has shifted into an age of numerous critics in numerous cities around the world. Many an essay regrets the decline and fall of literary criticism and the rise of blogger-rubes such as myself. But the death of any essential human pursuit is probably greatly exaggerated: literature takes on different forms, but the drives remain the same. And while any great art may be an elite pursuit, both art and art criticism are core human instincts. What are music, stories, books, and visual art doing? Which are good? What do we mean by good? Which can be re-read, imitated, talked back to, studied?

Literary criticism has, historically, had a relatively high barrier to entry—higher than literature itself, as criticism requires the construction of authority. For most of history, gaining the support of a wealthy patron helped. More recently, access to an important literary magazine or newspaper, often with funding from a nation-state or soft-power initiative. Women were mostly outsiders, although many of the women who were effectively literary “critics” created authority by hosting a literary salon, such as the one founded by May Ziade and frequented by Taha Hussein, Abbas al-Akkad, and others, although this did not prevent family from institutionalizing Ziade.

Indeed, this was the model for ArabLit, the blog I launched in Cairo in 2009. When I gave a talk at the American University of Cairo (AUC)’s Oriental Hall in 2012, as part of the Center for Translation Studies’ lecture series, I likened ArabLit to a digital literary salon; I have credibility not by my studies or talent, but by being amid talented people. Youssef Rakha’s “Arabophile,” which morphed into the Sultan’s Seal and Cairo Cosmopolitan Hotel, is even more of a digital salon with central literary personalities who have developed along with the website.

What we lose: marginalization of criticism

Gatekeeping has its upsides, and there are reasons to weep over the ashes of the Big Critic. Writers have railed against the closed-mindedness of twentieth-century literary criticism, and for good reason; yet the best of the Big Critics also helped build a vision of literary possibility. May Telmissany, for instance, writes in a recent essay “Edwar al-Kharrat: On Books and Writing” of how the great novelist and literary critic al-Kharrat saw the scope of her career when he wrote about her first collection of short stories, before she saw it herself. Al-Kharrat also had a keen eye for seeing emergent literary trends and forms, and for drawing attention to their possibilities, and younger writers often built on his ideas.

Egyptian critic and author Mansoura Ezz Eldin, in an email interview in 2019, talked about how the influence of long-form literary criticism has waned. “Criticism has been marginalized even more with the increasing strength of social media, such that it is almost absent from the literary scene; it’s true that there are still a number of writers who are keen to continue critical writing, but it’s no longer as influential as it once was, and broader segments of the reading public are choosing what they read on the basis of literary awards and comments on social media sites, or ratings on GoodReads and other sites, and to a lesser degree by quickie reviews in literary newspapers and magazines.”

This doesn’t mean we have obviated the need for in-depth, serious literary criticism, nor that literary criticism is on the verge of extinction. It probably does mean that criticism, in Egypt as elsewhere, is going through a shaggy period of between-ness. Old forms and forums are being abandoned for any number of reasons: an association with an autocratic state; an insular, limited view of literature; or because people have lost interest in reading a particular sort of review.

The current shaggy state of criticism, as Ezz Eldin notes, opens up room for exploitation. The weakening of centralized criticism comes at a time when Gulf-led big-money prizes, fairs, workshops, and festivals are creating new pathways for literary conversation. Social media sites also build a new credibility through popularity.

There are two sorts of literary criticism. The sort that is targeted at readers, and the sort that is targeted at writers. Social media and quickie rating-based reviews absolutely have a utility in making a reader feel connected to a larger community and in control of their reading life. Yet these do not fill the same need as long-form literary criticism, which is largely targeted at the community of writers. Thus far, BookTube, or the book-focused subculture among those who post video content to YouTube, has largely fallen into the first category, while literary podcasting has largely fallen into the second.

It’s important to note that, for Arabic literature, being at the margins of “world” literature also means that other-language criticisms can have an exaggerated effect, amplifying some voices and eliding others.

What we gain: Eluding borders, reinventing form

The Arabic literary podcast is only just finding its footing as a long-form literary conversation; a literary salon that takes place in all countries at once, and to which anyone can listen in. The physical literary salon has many charms, but was sharply limited by social class, geography, and personal affinity. Printed literary conversations could be made more widely available, yet they have, in practice, faced Arabic literature’s massive distribution issues, which affect not only movement between countries, but movement within them.

Literary podcasts in all languages can get around borders, building new conversations around literature. Most podcasts are open access. There are currently only a few literature-focused podcasts in Arabic, although there are culture-focused podcasts that sometimes touch on literature. The Jordan-based Sowt network is currently looking to develop a literary podcast in Arabic, but has not yet launched one. Kerning Cultures, the work of producers across the region, sometimes focuses on literature; Egyptian BookTuber Nada Alshabrawy also recently launched a podcast focusing on international women’s writing, although it requires a subscription on the Maktabi app. Ursula Lindsey and I launched an English-language podcast about Arabic literature in the fall of 2017, called “Bulaq.” Perhaps the most important Arabic-literature podcast is the Cairo-based “Sultan’s Seal” podcast with Mina Nagy and Islam Hanish, part of Youssef Rakha’s digital salon.

The “Sultan’s Seal” podcast launched in January 2019 with a short discussion of Mohab Nasr’s poetry. The form had sufficient appeal, both for its practitioners and its audience, that it began to appear every month, mid-month, and expanded into dialogues with some of Egypt’s most prominent authors: poet-novelist Yasser Abdellatif; translator Hesham Fahmy, who brought Game of Thrones into Arabic; novelist and translator Mohamed Abdelnabi, whose In the Spider’s Room was shortlisted for the International Prize for Arabic Fiction; novelist and critic Mansoura Ezz Eldin; nonfiction author Charles Aql, the author of Coptic Cuisine; surreal short-story writer Eman Abdelrahim; novelist and short-story writer Ahmed al-Fakharani; acclaimed novelist Nael Eltoukhy; poet Emad Fouad; and, in November 2019, the first non-Egyptian guest: Algerian poet-translator Salah Badis.

New online forms have birthed new possibilities. Rakha’s digital literary salon has spawned new video and audio forms that move between conversation and criticism, the intimately personal and the broadly philosophical. Mada Masr has been another force in re-seeing the possibilities of online literary criticism, moving the focus away from the contemporary to a wider scope for Egyptian classics. Mada has also pioneered the “Detox,” a multi-genre work they run on Fridays, which includes a literary “chitchat.” Although influence has often worked into Arabic, we can expect these forms to influence literary thought in English and beyond.

The role of Booktube

Many traditional TV chat programs still invite authors. After all, since Arabic satellite TV’s explosion in the early 2000s, there has been a great deal of airtime to fill. But most TV chats with authors center the author; YouTube channels center the reader/reviewer/interviewer, which is also how they create authority.

Egypt is 23rd in countries ranked by YouTube subscribers, between the Netherlands and Chile, and far behind Saudi Arabia, which is 14th, according to Channel Meter. Some Egyptian BookTubers, such as Nada Elshabrawy, started out making Facebook videos. Egyptian BookTube, more than blogging or podcasting, brings young people, outsiders, and newcomers to discussing books.

Anecdotally, Egyptian BookTube seems younger than any other form of literary criticism or conversation. Like other areas on YouTube, it is open to school- and university-aged creators. Most Egyptian Arabic-language BookTube channels, like US and UK English-language BookTube, feature a reader sitting or standing in front of a bookcase. Most talk for between five to ten minutes, sometimes loudly, and almost always in with a rapid-fire delivery. There are a number of smaller and intermittent Egyptian BookTube channels; most have fewer than five thousand viewers.

Four of the more popular and productive Egyptian BookTube channels launched in 2017: Saif Habashy’s “Salefny Ketab” (Lend Me a Book) launched in May 2017 and by November 2019 had more than 34,000 subscribers; Nada Elshabrawy’s “Dudit Kutub” (Bookworm) launched June 2017 and in November 2019 had more than 73,000 subscribers; “The Novelist” with Amr Maadawy, which also launched in June 2017, had more than 24,000 subscribers as of the end of November 2019. Mohamed Shady’s “Bita3 Kutub” launched in September 2017 and by November 2019 had more than 42,000 subscribers.

BookTube, as a whole, is seemingly influenced less by print literary criticism than by other YouTube channels, as well as film reviews, with focus on lists and stars, and a “no spoilers” policy. All of the above channels feature short videos; all are fast-paced; all have an educational or self-help bent, using humor and sometimes the personal life of the host.

Much of BookTube focuses on the book as commodity rather than as art or social disruptor. “The Novelist” is dedicated to discussing “the most important” Arabic and foreign novels, using the slogan, “Know Your Next Read.” Maadawy reviews novels with the stated goal of helping people find books that fit their tastes. “Lend Me a Book,” run by student Saif Habashy, is filmed in Habashy’s Alexandria home. Habashy, who told the Egypt Independent, “I’m not a critic,” added that he tells people “the content and price of a book.”[iv]

Nada Elshabrawy is the only one of the four who is an avowed writer—she’s a poet—although she doesn’t talk about poetry on the channel. She said, in a May 2019 interview: “I can’t talk about poets or poems without involving myself directly, and I don’t want to be advertising myself as a poet on my own show.”[v] Instead, the show addresses topics like, “How Can We Read More?” in a no-nonsense, personal, Marie Kondo-ish way. Each episode is scripted, although they feel natural.

ElShabrawy, who has traveled as a BookTuber, giving talks and participating in workshops, takes this seriously as a part of her profession, has said that her goal is to reach young readers and to help them read “as much as they can” so that they can “fall in love” with books. Although she’s said that she doesn’t consider what she does criticism, “I think the importance of booktubers in the overall book ecosystem is just like the importance of the critics and scholars in the past.”

Generally, BookTube has a focus on more prize-winning and popular authors: Mohamed Shady recently focused on best-selling horror novelist Stephen King. Maadawy has visited popular novelist Ibrahim Eissa in his office and has devoted a lot of time to the International Prize for Arabic Fiction. Egyptian BookTube has been noticed by the IPAF and the Abu Dhabi Book Fair, which has put considerable emphasis on social-media celebrities; Elshabrawy and Maadawy were at the 2019 fair.

This new YouTube criticism currently lends a fair piece of its enthusiasm to big books and Gulf soft-power initiatives, particularly the Gulf’s big literary prizes. It is, at present, more commodity-oriented than either podcast or print. This in itself is not a positive development for the literary arts. But in building a new space to talk about books, these channels are also building a future where more — new language, new audiences, new genres — is possible. Perhaps, in the near future, criticism/intiqad will no longer be how we want to describe modes of evaluating and illuminating literature’s pathways. In a 2018 essay-post, “In Search of Sanity,” Mada Masr culture editor Yasmine Zohdi expressed her discomfort with the moniker of “critic,” and underlined our need for a fresh critical (or illuminative) language. Perhaps the word critic/naqd will become antiquated as we work toward new ways of evaluating literature; why not? But the essential relationship endures.

M Lynx Qualey is the founding editor of the ‘ArabLit’ website (www.arablit.org), which won a 2017 London Book Fair “Literary Translation Initiative” prize. She also publishes the experimental ArabLit Quarterly magazine and is co-host of the Bulaq podcast. Her co-translation of the middle-grade novel Ghady and Rawan was published in August 2019 by University of Texas Press, and her translation Sonia Nimr’s Wondrous Journeys in Amazing Lands is forthcoming (fall 2020) from Interlink. She writes for a variety of popular publications and currently lives in Rabat, Morocco.

Image captions: 1) M Lynx Qualey and Samia Mehrez at a Center for Translation Studies lecture; 2) Egyptian novelist Mansoura Ez Eldin; 3) Egyptian novelist Muhammad Abdelnabi; 4) “Bookworm” Nada Elshabrawy; 5) Booktuber Saif Habashy; 6) Booktuber Amr Maadawy.

Cairo Since 1900: Book Review and Interview with the Author | by Shaimaa S. Ashour

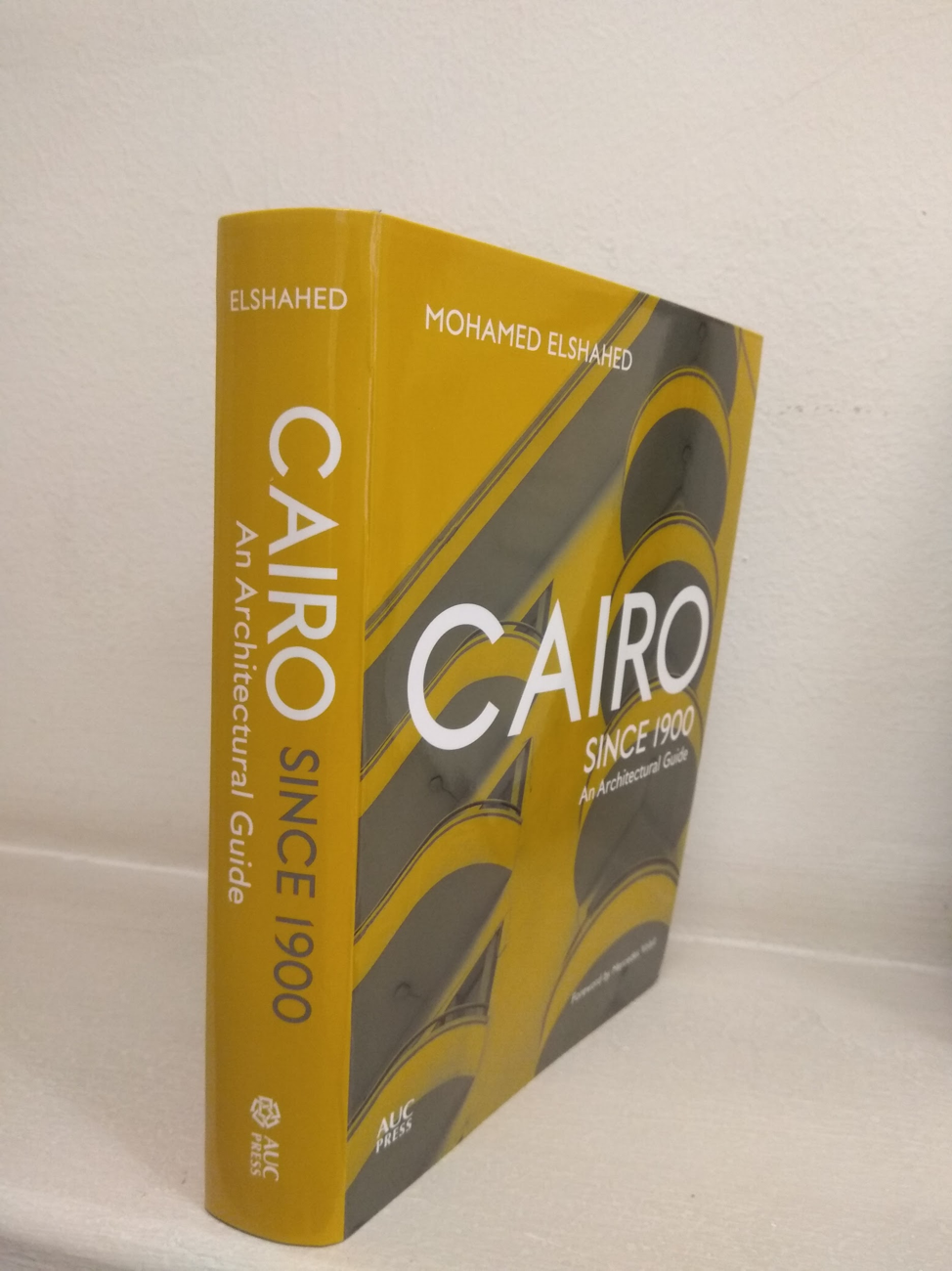

Mohamed Elshahed, Cairo Since 1900: An Architectural Guide, (New York: The American University in Cairo Press, January 2020), 410 pp. | ISBN 9789774168697 . | $39.95.

Roots of the idea and sources of inspirations

In 2002, I became interested in Egyptian nineteenth and twentieth-century architecture. When I started looking for books on this topic, I found very few. The oldest was Muhammad Hammad’s book Misr Tabni (Egypt is Building or Egyptian Buildings) (1963) in Arabic. Then by the 1980s , five books were published; two in Arabic by Tawfiq Abd al-Gawwad: ʻAmaliqat al-ʻimarah fī al-qarn al-ʻishrin (Pioneer Architects in the 20th Century), Misr: Al-‘imara Fi-l- Qarn Al-‘ishrin (Egypt: The Architecture in the 20th century), two in French by Mercedes Volait: Al-‘imara: et Le Debat Architectural en Egypte dans Les Anees 1940 – 1960 (Al-’imara / The Architecture and the Architectural Debate in Egypt, 1940-1960), and L’Architecture Moderne En Egypte et La Revue Al’Imara, (1939-1959) (Modern Architecture in Egypt and Al-’Imara Magazine (1939-59)), and one in German by Mohamed Scharabi: Kairo: Stadt und Architektur im Zeitalter des Europaischen Kolonialismus (Cairo: City and Architecture in the Age of European Colonialism).

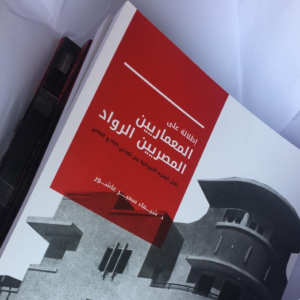

Thirty years after Scharabi, I published my book Al-m’mariiyn Al-misriiyn Al-ruwwad Khilal Al-fatrat Al-liybiraliah Bayn Thawratay 1919 wi 1952 (The Pioneer Egyptian Architects during the Liberal Era (1919-1952)) in Arabic. The first edition was published in 2011, as part of the book series Safhat min Tarikh Masr (Pages from Egyptian History) by the Madboly Publishing House, while the second edition was self-published in 2017. My book provides an overview of Egyptian architecture during three decades, starting with Egypt’s 1919 independence and ending with the 1952 revolution. The book has a special focus on the works of two architects: Antoine Selim Nahas and Aly Labib Gabr, and it consists of a deep study of the impact of political, economic, and socio-cultural factors on the local Egyptian ideology and architecture of that era. I cannot review Mohamed ElShahed’s Cairo since 1900: An Architectural Guide without comparing it to all the previously mentioned books. Hammad was presenting architecture of his own lifetime while Scharabi was interested in a certain period, style and area. Volait’s and my own book cannot be classified as architectural guides, but rather as in-depth comprehensive historical books synthesizing many contextual details.

Thirty years after Scharabi, I published my book Al-m’mariiyn Al-misriiyn Al-ruwwad Khilal Al-fatrat Al-liybiraliah Bayn Thawratay 1919 wi 1952 (The Pioneer Egyptian Architects during the Liberal Era (1919-1952)) in Arabic. The first edition was published in 2011, as part of the book series Safhat min Tarikh Masr (Pages from Egyptian History) by the Madboly Publishing House, while the second edition was self-published in 2017. My book provides an overview of Egyptian architecture during three decades, starting with Egypt’s 1919 independence and ending with the 1952 revolution. The book has a special focus on the works of two architects: Antoine Selim Nahas and Aly Labib Gabr, and it consists of a deep study of the impact of political, economic, and socio-cultural factors on the local Egyptian ideology and architecture of that era. I cannot review Mohamed ElShahed’s Cairo since 1900: An Architectural Guide without comparing it to all the previously mentioned books. Hammad was presenting architecture of his own lifetime while Scharabi was interested in a certain period, style and area. Volait’s and my own book cannot be classified as architectural guides, but rather as in-depth comprehensive historical books synthesizing many contextual details.

Cairo since 1900 is the first architectural guide to Cairo’s modern architecture and in a refreshing approach, buildings are not presented chronologically but geographically. In an interview I conducted with him in [December, 2019] Mohamed Elshahed explains the reason behind this choice: “we experience the city as a geographical location, not as time-travelling. Thus, buildings are presented in each district geographically as if I am ‘guiding’ the reader along Cairo’s streets.” One century of modern architecture is narrated through a selection of buildings outside how we normally classify Cairo’s architecture by districts, or styles or according to building scale, typology, or era. Initially, Elshahed did not focus on the much studied districts of Downtown, Zamalek, and Garden City. Rather, he extended the scope of the guide to include more than fifteen districts; this includes areas that are often overlooked, like Sayeda Zeinab, Daher and Nasr City. Since Downtown is the largest district in the area, it has the largest number of buildings in the guide. Even there, Elshahed does not classify the buildings according to their style, explaining, “this guide does not focus on a certain social class or European influences. Thus, buildings are not identified as styles but rather presented as tectonic composition; each had a certain statement or point of view that was developed through a process. Art approaches cannot suit architecture anymore.” When the author mentions art approaches, he is referencing the fact that art approaches run into two major obstacles when used to study architectural history: first, a majority of buildings in the city do not come from purely one particular style, but are rather a product of multiple styles, thus any attempt to classify the architectural history of the city into sequential styles is difficult without gross oversimplification, second, architecture is not like an art form with a single creator; in Egypt, architecture and engineering are overlapping fields. Many buildings are a product of both fields, and in some cases, civil engineering played a much more important role than architectural concerns. For instance, in the guide on Saint Mark’s Coptic Cathedral, Elshahed mentions civil engineer Michel Bakhoum as well as architects Awad Kamel Fahmy and Selim Kamel Fahmy. Moreover, in more than 15 buildings, the architect is completely unknown, like the two iconic buildings Ahram Beverages Company and École Alliance Israélite Universelle.

Elshahed also explores how wider ideological preferences may bias the viewer against the city’s more modern architecture. Specifically, he points out how the colonial perspective and nationalist responses to colonialism may result in the branding of modern architecture as ugly buildings. Not only here in Egypt, but worldwide, we equate between modernism and ugliness with the ultimate result that the demolition of those buildings does not strike us as a significant loss. In contrast, Elshahed argues that we need to alter aesthetic judgment to include 20th century architecture.

Elshahed believes that the discourse on the city and its architecture should be based on wider societal participation and engagement.This can be achieved by promoting awareness of modern architecture through a user-friendly guide. Thus, his target readers are students, locals and tourists. This can be seen, first, in the size of the volume, meant to fit into a pocket. Second, abstracted maps of districts with specific buildings identified facilitates self-guided walks. Self-guided tours are also made easier through scanning a QR code to cairosince1900.com/go*, where the reader can enter a building number as listed in the guide to be taken to its GPS location on Google Maps. Third, a glossary defining architectural terminologies from the Cairene perspective provides newcomers with an introduction to key terms. Elshahed explains further: “I cannot speak about brutalism in Cairo without mentioning Sayed Karim.” In all, this guide is suitable for a broad audience; it is not too technical, nor too simplified and anyone can easily access the information they need to enjoy Cairo’s architectural legacies.

Stars in the shadow

“I started working on the guide in 2015/2016 with a team of 10-15 for field surveying. The working plan started with one year to identify buildings, aiming not to start from already published sources rather starting from the street directly. Six months later, I started writing. This guide took three or four noncontinuous years, it would have taken half the time if the information were accessible and the streets were friendly.”

Here, Elshahed points out two important problems: a lack of information and the difficulty of street surveys. Nevertheless, Elshahed and his team have exceeded expectations, providing a wealth of information on various topics despite harsh street conditions with buildings continuously changing and the difficulty of taking photos.

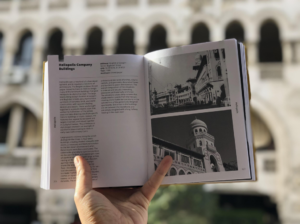

The book must also be praised for its design; it is a combination of neatly reproduced plans, mixing photos with advertisements and concise essays. Elshahed mentions that more than double the number of plans that were reproduced were excluded from final publication. The plans of the buildings do need to be larger in size as many scholars need those conventions. The guide is also indexed with side titles, thus easily orienting the reader. Finally the guide’s cover is a photo for Waqf Gamalian Buildings: the Gamalian, as the guide tell us “with its distinctive streamlined modern lines, circular balconies cantilevered at the corners, and its immense scale…is an unmatched landmark in Cairo” (53). I wonder if there is any relation between the yellow color of the cover and Cairo’s dust?

Flipping Through the Guide

The guide starts with a historical introduction on building modern Cairo, starting in 1900 through the present. It is divided chronologically into three periods, each ranging from 40 to 50 years. In this section, Elshahed weaves together historical events, the ideology of each period, and significant architects working in this period with precedents of modern architecture. This introduction is followed by a maps section for all districts in the same scale. Cairo is a difficult city to draw or translate into map form. Thus, in some districts, buildings are spread and in others they are condensed, like Abbasiya versus Downtown. This is mainly because of the changing names of the streets between official maps, Google maps and local, unofficial names.

The guide originally intended to include 600 buildings then downsized to 226 buildings and sites of note. Each entry starts with basic information: address, GPS, year and architect. It is then followed by concise, explanatory text describing the building and its significance accompanied by photographs and conventions. This was done in a non-typical representation context suitable for each case. It is worth mentioning that building descriptions are as faithful to the original design as possible, with notes regarding major alterations or changes that have happened over the years. Elshahed explains the logic behind this choice: he says architecture is a dream. The best ideas happen in dreams or the concept stage, not in execution. Architecture changes in the implementation process, especially in Egypt. For instance, Sayed Kareem designed one or two-story podium in many housing models containing daycare facilities, stores, a cinema, a clinic, and other services, as well as a sculptural roof garden above the building; however, neither podium nor roof garden was implemented. As another example, in the initial design, the tower of the State Council was imagined “as a curtain-walled twenty-story block, but it was implemented shorter, with a regular grid of windows” (222).

The guide originally intended to include 600 buildings then downsized to 226 buildings and sites of note. Each entry starts with basic information: address, GPS, year and architect. It is then followed by concise, explanatory text describing the building and its significance accompanied by photographs and conventions. This was done in a non-typical representation context suitable for each case. It is worth mentioning that building descriptions are as faithful to the original design as possible, with notes regarding major alterations or changes that have happened over the years. Elshahed explains the logic behind this choice: he says architecture is a dream. The best ideas happen in dreams or the concept stage, not in execution. Architecture changes in the implementation process, especially in Egypt. For instance, Sayed Kareem designed one or two-story podium in many housing models containing daycare facilities, stores, a cinema, a clinic, and other services, as well as a sculptural roof garden above the building; however, neither podium nor roof garden was implemented. As another example, in the initial design, the tower of the State Council was imagined “as a curtain-walled twenty-story block, but it was implemented shorter, with a regular grid of windows” (222).

Regarding latter alterations in a building’s architecture, Elshahed is well aware of the fact that there was no system of preservation for modern buildings; they may change any time, so a building’s description in 2015 may differ drastically from its description in 2019. Thus, per Elshahed’s example, it is better to describe the original and hint at changes.

As for his criteria for which buildings to focus on, Elshahed explains:

“This is not the project of my selections or even selecting the best of [Cairo]; my aim is to highlight representative samples produced through the twentieth century. Not necessarily masterpieces, a category that often shapes the selection of buildings for guides like this. It is material evidence of the evolution of the city; they are partly the result of the aesthetic decisions made by the architects and their patrons, but also the result of economic, political, cultural, and municipal conditions impacting the time and place of their construction. But the last decision of selection was shaped by archival sources and available data.” (23-25)

He also gives pointers to help the students conducting the survey, asking them not to search for the architecture they already knew, but rather, expecting them to discover the unknown. He sees architecture as a product of political, economic, and cultural factors, not as good or ugly aesthetically. Even if unfinished,a building tells us something about a place. Have a look at all the churches chosen in the guide, most of them have unconventional design. Take a look at All Saints Cathedral, Virgin Mary Church (Al-Maraashli church), or the church of the college of the de la Salle school. Another example is Al-Halabi Print House, “(also known as al-Maimuniya) specialized in printing and publishing historical Islamic texts, as well as the Qur’an. It was the largest print facility of its kind in the region, with international distribution reaching East Asia and West Africa, and a printing capacity in the 1940s of seven million books a year” (297). The U-shaped, two-story, concrete building comprises a non-Islamic style, opposing the expected.

Wide uncommon diversity in typologies and time periods

Elshahed includes samples exemplifying typical and canonical trends as well as specimens expressing unique formulas. Some of the works reviewed are just proposals like the Islamic Congress Secretariat or Expo City, while others are unfinished, like the 1952 Revolution Museum. He also includes demolished buildings, as well as standing buildings like the AUC Science Building. In the guide, we find everything from bridges to gardens, from iconic buildings to unknown residential buildings with a story to be told. This broad range does not come at the price of detail. For instance, the Exhibition Grounds (now the Opera Grounds) and Opera House are not condensed and treated as one entity, but are detailed as two separate structures. This range extends across chronological barriers too, with buildings from different eras detailed side-by-side in the book. All are important to complete the image of the potential of a certain locale.

Worth mentioning here are the details Elshahed includes about the amount of time taken to build each structure; such details provide historical context and convey much about the building process. For instance, the High Court, originally designed for the city’s mixed tribunals, was the result of an international competition, with winners announced in 1924. While construction started in 1925, the building process was slow and faced delays, pushing its inauguration back to 1934. Had the author just mentioned that the building was opened in 1934, a story of ten years would have been erased: the building’s importance to the 1919 revolution, the construction process that stopped twice, first, for financial reasons when costs greatly exceeded the budget and second, due to construction problems. Another example is the 1952 Revolution Museum originally built in 1951 by the palace to function as a rest house and a dock for the royal yacht:

“The building was never used for its original purpose, due to the abrupt end of the reign of King Farouk. Subsequently, the officers used it as their Revolutionary Command Centre. In 2003 construction work commenced to implement designs by Ahmed Mito to transform the building into a museum. The renovation saw the construction of steel ribs in the shape of a bird taking flight, representing the Eagle of the Republic, above the roof of the otherwise Neo-Classical edifice.” (265)

Thus, it was built in 1951, redesigned in 2009, and is expected to open by 2020.

I would like to conclude by providing a few interesting stories from the guide and from my interactions with the author.

In the interview I conducted with him, Elshahed was able to provide greater insight about his engagement with the buildings he skillfully covered in his guide. It was quite obvious when I asked Elshahed about his top five buildings from the guide, he mentioned the Al-Azhar University Campus, Housing Model 33, Villa Sayed Karim, Abusir House 2 and Al-Kateb Hospital. Actually, I guessed two out of the five: Housing Model 33 and Villa Sayed Karim. I think Sayed Karim is a mentor for Elshahed. Initially, you can read it between the lines in Cairobserver, then, sayed Karim pictured at the beginning of the guide followed by photo for the main stairs at Villa Sayed Karim. Last, more than 40 buildings in the guide were designed by sayed Karim, that made him on top of index of architects at the end of the guide.

As I mentioned, the guide is full of interesting stories. Here is one of them about the Merryland Apartments: “The Merryland Apartments were partially realized twice, first in Heliopolis and again in Maadi. At the Heliopolis site, the unbuilt cylindrical block would have included eight three-bedroom apartments per floor. This block was implemented in the Maadi iteration of the project. The long, slightly curved middle block contains thirty duplexes every two floors, and the twenty-story tower houses twelve three-bedroom apartments per floor. The tower was not implemented in the Maadi version” (330).

In an otherwise flawless volume, one minor correction should be noted. On spotted lapse, the caption of the photo on p. 32 notes the names of two architects, (Gabr and Fahmy) incorrectly. The correct caption should read: “Architectural conferences and symposia took place regularly in Cairo, particularly in the period following the end of the Second World War. A group photograph from 1949 at an architectural gathering shows (from left to right) architect Ali Labib Gabr, English town planner (Greater London Plan of 1944) Sir Leslie Patrick Abercrombie, Mustafa Fahmy and his wife, Ahmed Sedky, and Abdulmoneim Heikal.”

Overall, this impressive guide is one of the endless possibilities of guides that could be written about Cairo in that period. Its aim is not to declare that these are the 226 buildings to be preserved, but rather to better understand how to read the city through them.

This essay is based on reviewing the book and an interview with the author, Mohamed ElShahed, in December 2019.

*Stay tuned, the site will be active soon.

Shaimaa S. Ashour is an architect with multi-disciplinary interests ranging from Egyptian 19th and 20th century architecture to cultural heritage, architectural advertisement and urban history. She is an assistant professor at Arab Academy for Science, Technology & Maritime Transport.

Art as Education: Street Art as a Precursor to Social Change | by Marwa Gadallah

Encounter between Artist and Observer

A revolution does not merely constitute a crowd of dissenters that stand against the prevailing order. It comes alive when a structured network is put in place and acted upon. Then, as visual artist, activist, and academic Bahia Shehab writes, “…we need to find our rightful place within this revolutionary structure.” In this structure, there is the protester, there is the journalist and the photographer, there is the artist and the poet, and there is the writer and the blogger. A single street artist, for instance, derives her artwork’s subject matter from the roles of others within the structured network. Her immediate surroundings, including the chanting protestors, can all contribute to the message that her artwork will proclaim. Then, just as these events are the context from which the artwork is born, the artwork, too, becomes a context from which other players within the revolutionary structure derive their own role. With work spanning the globe and several genres of visual art, including Arabic calligraphy, Bahia designs this context through her wall paintings, which she creates on streets in various parts of the world. In this process of meaning-making, what may be overlooked is the context or environment that is created while the artwork is actually coming to life. This involves the encounter between the working street artist and the passersby or the volunteer painters. This article explores the contours of this encounter and specifically asks how this encounter becomes an opportunity for education and social change.

A Thousand Times “No” on the Streets of Cairo

Bahia’s 2010 installation “A Thousand Times No” involved documenting the development of the letterform of the Arabic “lam-alif,” which translates into “no.” She later made use of the context of the Egyptian revolution of 2011 to display these various “no’s” on the walls of Cairo’s streets (Figure 1). She protested against and said “no” to such phenomena as violence, the stripping of protesters and the burning of books. Today, however, people are torn between their need for sociopolitical change and their need for a more stable life where their everyday needs are met in peace without the turmoil that a revolution brings about.

Mahmoud Darwish and the Inaccessible Dream

The more she studied and participated in the world of street art, the more Bahia began to notice a culturally diverse yet universal application of the artform. Beyond her “no” paintings, Bahia found new Arabic messages in the poetry of Mahmoud Darwish that were relevant to an international context and the state of the world at that moment. As a designer, she ensured that her Arabic calligraphic styles were relevant to a more modern audience. As such, much of her artwork employs letterforms that are inspired by simple geometric shapes. In Vancouver, Canada, she painted her first message from Darwish, which translates into, “Stand at the corner of a dream and fight” (Figure 2). This simple Arabic message is relevant even in Vancouver, since the idea of pursuing dreams has become a general matter of interest around the world. As

she was working on the piece, she noticed many people doing drugs on the street – a poignant reminder of the relevance of Darwish’s message and the importance of pursuing a dream and fighting for it even during such difficult times.

In Marrakesh, Morocco, the context of an Arab world filled with poverty and the sheer incapacity to make a living on the one hand, and the large number of young people who are ready to work on the other, inspired Bahia to paint Darwish’s, “We love life – if only we had access to it,” in the city’s streets (Figure 3).

Street Art, Mobilization and Acceptance of the “Other”

Street art does not only last for a period of time to give passersby the opportunity to see and understand its message but the nature of its environment allows even the creation process to become a learning experience for those participating in its creation. In Madison, Wisconsin, for instance, Bahia painted, “No to the impossible,”in Arabic alongside a team of film producers, students, professional muralists and an army veteran, all from diverse ethnic backgrounds (Figure 4). Th e fact that these very different people were gathered to create a painting with a common message that encourages persistence despite obstacles created an air of belonging among those present. This is such that one of the volunteer painters made the comment, “Teamwork makes dream work,” upon solving an issue with the piece, which is quite in line with the idea of the message, “No to the impossible.” This sense of belonging created by Bahia’s artistic environment encouraged members of the team to share their stories with each other, allowing an opportunity to hear and learn from people of different walks of life. To reconnect this idea to our opening focus on the impact of this type of street art, we can see in this experience how the creative process mobilizes the artist and the immediate audience to work towards the common goal of conveying the message of social change. It also allows people who are very different from one another to accept the “Other” in that moment of shared purpose.

e fact that these very different people were gathered to create a painting with a common message that encourages persistence despite obstacles created an air of belonging among those present. This is such that one of the volunteer painters made the comment, “Teamwork makes dream work,” upon solving an issue with the piece, which is quite in line with the idea of the message, “No to the impossible.” This sense of belonging created by Bahia’s artistic environment encouraged members of the team to share their stories with each other, allowing an opportunity to hear and learn from people of different walks of life. To reconnect this idea to our opening focus on the impact of this type of street art, we can see in this experience how the creative process mobilizes the artist and the immediate audience to work towards the common goal of conveying the message of social change. It also allows people who are very different from one another to accept the “Other” in that moment of shared purpose.

This mobilization process is als

o quite evident in Bahia’s work in Amsterdam where she painted in Arabic a line from Darwish’s poetry that read, “One day we will be who we want to be. The journey has not started and the road has not ended” (Figure 5). The volunteers who worked on painting the wall alongside Bahia included archaeologists and university students who were from diverse cultures and backgrounds. Two of them spoke with Bahia about their opinions regarding Brexit and were in support of unity. Here, a perfect example of intercultural exchange is portrayed: An Arab artist speaks about Brexit with young Europeans.

Cross-Cultural Comparisons

In Cephalonia, an island which lies on the Ionian Sea, a part of the Mediterranean Sea, the dangerous journeys of refugees across the waters of the Mediterranean served as the context for Bahia’s artwork. The wall painting, which was created at an Olympicswimming pool in a sports complex (Figure 6), read in Arabic, “Those who have no land have no sea.” The letterforms were designed in the shape

of sailboats in honour of those who made the perilous trips by sea in order to escape their war-torn countries and, in many cases, died along the way. As she was working on the artwork, an opportunity for cross-cultural communication presented itself when a curious swimmer came up to ask her about her work. When Bahia learned that he was training for the Olympics, she was able to draw on her own background as an Arab and her concern for Arab issues to notice the deep contrast between the refugees fighting the waters in search for a safer home and the fact that the waters were flowing in this young swimmer’s favour, allowing him the chance to compete and get ahead in life.

Cross-Cultural Interaction and Educational Experiences

Through her artwork, Bahia has also managed to encourage Arabs to interact with others in European countries in light of their Arab culture. In Stavanger, Norway, she painted the phrase, “How big is the idea, how small is the state” (Figures 7 and 8). As she was painting the wall, she also spoke with many people around her. Among these was a woman named Mary who lived in the building overlooking the wall that Bahia was painting. Mary asked Bahia to paint another corner of the wall so that she could see a well-designed wall when she looked out of her window. Another Arab woman, a young Syrian Muslim named Amal, thanked Bahia for painting in Arabic in her neighbourhood and for encouraging the idea that not all Arabs are terrorists. Later, Bahia was shown a photo of Syrian students translating the words of her artwork to their non-Arab colleagues in a process of cross-cultural interaction. As such, Bahia’s work creates the necessary environment that encourages this form of educational experience. It also creates an environment of awareness that combats the racism and discrimination that is often unjustly directed at Arabs.

looked out of her window. Another Arab woman, a young Syrian Muslim named Amal, thanked Bahia for painting in Arabic in her neighbourhood and for encouraging the idea that not all Arabs are terrorists. Later, Bahia was shown a photo of Syrian students translating the words of her artwork to their non-Arab colleagues in a process of cross-cultural interaction. As such, Bahia’s work creates the necessary environment that encourages this form of educational experience. It also creates an environment of awareness that combats the racism and discrimination that is often unjustly directed at Arabs.

Cross-Cultural Hostility

Oftentimes, however, cross-cultural communication may be met with hostility in the form of racism. This is what Bahia encountered in Paris, France as she worked on a wall where she painted the words, “I will dream,” in Arabic (Figure 9). Just as the environments that Bahia creates while she works on her walls can foster positive forms of cross-cultural communication and education, they may also en courage hostility, the very thing that they are meant to stand against. This is because these created environments cannot be stripped of the greater context in which they are born. In this case, the context is the prevailing air of racism that continues to linger on the streets of Paris. As she worked on the wall with her friend, several people responded to the Arabic writing on the wall in a racist manner, emphasizing an air of cross-cultural hostility. However, the positive aspect here lies in the fact that the creation process helped to further highlight the racism, which could later encourage a dialogue and, perhaps, even change.

courage hostility, the very thing that they are meant to stand against. This is because these created environments cannot be stripped of the greater context in which they are born. In this case, the context is the prevailing air of racism that continues to linger on the streets of Paris. As she worked on the wall with her friend, several people responded to the Arabic writing on the wall in a racist manner, emphasizing an air of cross-cultural hostility. However, the positive aspect here lies in the fact that the creation process helped to further highlight the racism, which could later encourage a dialogue and, perhaps, even change.

An Arab Artist’s Effort to Create Involvement and Ownership

As demonstrated, street art has the ability to create an environment that involves people in the immediate community and encourage them to play a more participatory role. This, in turn, encourages them to truly own the walls of the space in which they live. What is more interest

ing is how this may be done in a cross-cultural setting where an Arab artist facilitates this process of interaction and ownership for people who live in spaces that are foreign to her.

Art as a Precursor to Social Change

For social change to occur, there must be a beginning from which the fruit may grow. Today, in a world that is still overcast by racism, discrimination and violence, practical social change is not likely to occur in a smooth and peaceful manner. For social change to flourish, we must first engage in a process of education that allows us to understand the nature of our situation and acknowledge the problems and then better understand how we can address these problems. Bahia’s active engagement with the community through the environments that she is creating provides a basis for the cross-cultural dialogue that will encourage people to begin to think.

Marwa Gadallah is a graphic designer who is based in Cairo, Egypt. She is also a graduate of the Graphic Design program at the American University in Cairo. Her graduation project was on disseminating the socially and politically charged concept of Orientalism as presented in Edward Said’s book using a combination of visual and textual elements to a young Egyptian audience. She is also venturing into the field of political cartooning where her interest in visualizing social and political topics lies. She has also done design work for the finance sector. Some of her work can be viewed through this link: https://www.behance.net/marwa-gadallah.

Image Captions: 1– “No’s” sprayed on a wall, Bahia Shehab, Cairo, Egypt ; 2– “Stand at the corner of a dream and fight”, Eyoälha Baker, Vancouver, Canada ; 3– “We love life – if only we had access to it”, Yousséf Belbahri Achir, Marrakesh, Morocco; 4– “No to the impossible”, Bahia Shehab, Madison, Wisconsin; 5–“One day we will be who we want to be. The journey has not started and the road has not ended”, Bahia Shehab, Amsterdam, the Netherlands; 6–“Those who have no land have no sea”, Ghalia Elsrakbi, Cephalonia; 7– “How big is the idea, how small is the state”, Brian Tallman, Stavanger, Norway; 8– “How small is the state”, Brian Tallman, Stavanger, Norway; 9–“I will dream”, Arullan, Paris, France.

Citations

Shehab, B. (2009). At the Corner of a Dream. London: Gingko.

Umm Kulthum Conquers all: Kawkab al-Sharq through Pop Art | by N.A. Mansour

When it comes to the great divas of Arabic song, there’s this saying: you listen to Fairuz in the morning, to Umm Kulthum at night. I didn’t use to subscribe to that notion, even though I had seen plenty of people indeed blast Fairuz in the morning and Umm Kulthum at night. But in all my obstinance, I rejected it straight off, even as a child. Instead, I believed that the world was really divided into two types of people: Umm Kulthum people and Fairuz people. I was born a Fairuz kind of woman. Afterall, a true mutriba, Umm Kulthum sang long ballads running up to 40 minutes long in a husky voice my impatient ear hesitated to call beautiful. Fairuz’s voice was like silk and had a haunting lilt reminiscent of tajwid, the art of Qur’anic recitation I was being taught in primary school. Besides, al Sitt, Umm Kulthum was Egyptian; I am not.

There were other whispers in my ear, telling me I was a Fairuz kind of woman and not Umm Kulthum’s. I grew up in a world where the trivial was to be avoided. My homeland was at war, so fantasy novels were to be kept to a minimum. We would not watch movies at the cinema and instead wait for the home release. Food was never to be wasted, every sesame seed swept from the table and deposited into our mouths. But Fairuz was alright because she sang for our cause: for Jerusalem and with it, all of Palestine. I was thus allowed – by my father and my society – to fall backwards into her eclectic canon, from Ya Bint Shalabiyya to the funky al-Bostah, which hearkened back to provincial life with its lyrics laden with gossip but did so to a beat I learned to later call ‘funk’. In my memory, Fairuz is the sound of my small Palestinian village in the early 2000s. I carried her with me across the world, into college and beyond. I bought a long-sleeved t-shirt with Fairuz’s face on it the year I lived in Jordan, post-college. I bought the shirt from one of those boutiques that mixes identity politics and pop art, because I was nostalgic for the person I had been throughout college: in love with pop culture and not afraid to show that love in its most blatant form. But that person was changing. I was slowly morphing into an academic, into someone who aspired to belong to the intellectual class. I wanted my aspirations to be taken seriously; these are the anxieties of a woman who studies her own culture. So I did not wear the shirt and it eventually went to live in my storage locker, where it still is today. Instead, I wore riding boots with dark jeans and floral tops. This was the uniform of an academic, I told myself.

At graduate school, I still didn’t listen to Umm Kulthum. Instead, I dove into the rich oeuvre of post-Arab Spring Arabic rock. I traveled everywhere but Egypt because I believed – and I still believe to some extent – that Egypt should be de-centered in narratives of the Middle East and North Africa. Egypt’s sheer cultural output cannot be disputed, but I wondered of the damages of that narrative. Umm Kulthum loomed large in my mind as a symbol of that scale, with those epicly long songs and with the detail she expected from every production (and from herself). I had been given a postcard of her at an exhibition of Egyptian film posters. I begrudgingly framed it with other pop-culture memorabilia, a student’s alternative to buying art. I fawned even more over the Abdul Halim Hafez postcard I had received at the same event; my friends and I had swooned over him in our teens, the unattainable dark nightingale. He made sense to me, while Umm Kulthum still did not. I held onto him, Fairuz, and Arabic rock as signifiers of who I was, even as I became more firmly labeled in my self-image as an intellectual and as an elite. It’s what happens to people who want to be historians. I quietly lamented the loss of that young girl who belonged to a village community and wasn’t afraid to show her allegiances through her choices in dress and her angry emboldened voice, but I also knew this was who I had always aspired to be. I would not admit it, but I was torn between who I wanted to be, who I was raised to be, and who I was.

I went to Egypt to do dissertation research because it was deemed necessary by the institutions and structures which envelope me, in order to check it off the list of things historians of Islam must do; you have to write about Egypt in some measure if you’re writing about the Arabic-speaking world. I maintained it would be a quick trip: I would be in and then out. I am, after all, a creature of small lush country towns, not a city person, not a desert person. I would not like it, I thought, just as I had always been averse to Umm Kulthum. But something softened within me when I arrived in Cairo. The world was less black and white. I asked questions instead of jumping to conclusions and slowly, inexplicably I fell in love with Umm Kulthum and she began to tackle the tensions I felt within myself, one by one.

I began recognizing her lyrics – that’s how I knew it was beginning. The lyrics would come to my mind when speaking. I’d be telling someone, for instance, how expensive something was and ya aghla min hayati, you who is more valuable than my life, would almost make it to my lips. I would hum the melodies too, especially the long instrumentals that prelude her vocals. Especially those. I asked cab drivers to raise the volume when she came on and we would hum together, bonded for a few moments. I walked, then ran to her catalogue, exploring a long career that burned brightest in the years immediately prior to her death: my favorites remained the classics Alf Layla wa Layla and Inta Omri. The process was complete: I had been conquered by al Sitt, kawkab al-sharq, the diva, Umm Kulthum.

I bought a necklace with the title lyrics from Inta Omri at a boutique in downtown Cairo that no longer exists. It was in the shape of a hand, reminiscent of amulets meant to ward off different maladies. Casting Umm Kulthum as an amulet appealed to me. Not only was it a marriage between two different forms of popular culture, but I felt it meant she protected me; some twisted form of thawab. The songs were a bit like that, too. Like the Qur’an, but to a far lesser extent: if I listened to them, I could not go astray.

I left Egypt soon after realizing the extent of my love for Umm Kulthum. I kept the amulet around my neck and her songs in my ears. I still fought against romanticizing al Sitt; romanticizing Umm Kulthum, like romanticizing Cairo, could only do damage to the rest of the Arab world. The rest of us have stories; we create art that is innovative and charming and we have ideas.

I left Egypt soon after realizing the extent of my love for Umm Kulthum. I kept the amulet around my neck and her songs in my ears. I still fought against romanticizing al Sitt; romanticizing Umm Kulthum, like romanticizing Cairo, could only do damage to the rest of the Arab world. The rest of us have stories; we create art that is innovative and charming and we have ideas.

Cairo and Egypt were not and should not be al-qahira, the conquerer and arbiter of taste who loomed above all, mostly above the Arabic-speaking world. But I could not ignore how Umm Kulthum, beyond her voice, connected us to one another – anyone who identified culturally with her that is. Even as someone who is multicultural, multiracial, and multilingual, I do believe some connections can not be made with peoples of other backgrounds; try as hard as we might, lines of race, culture, religion, and economy cannot always be crossed. But where there is al Sitt, I began to realize, I could cross some lines that were otherwise impenetrable, aided in some ways by the language I speak, the fabric I wear on my head and my dark eyes. When in Egypt, I could admit to Egyptians that she was the best and begin a conversation that way. Our woes would come out through her lyrics. So could our joy. I had not been able to do that with Fairuz.

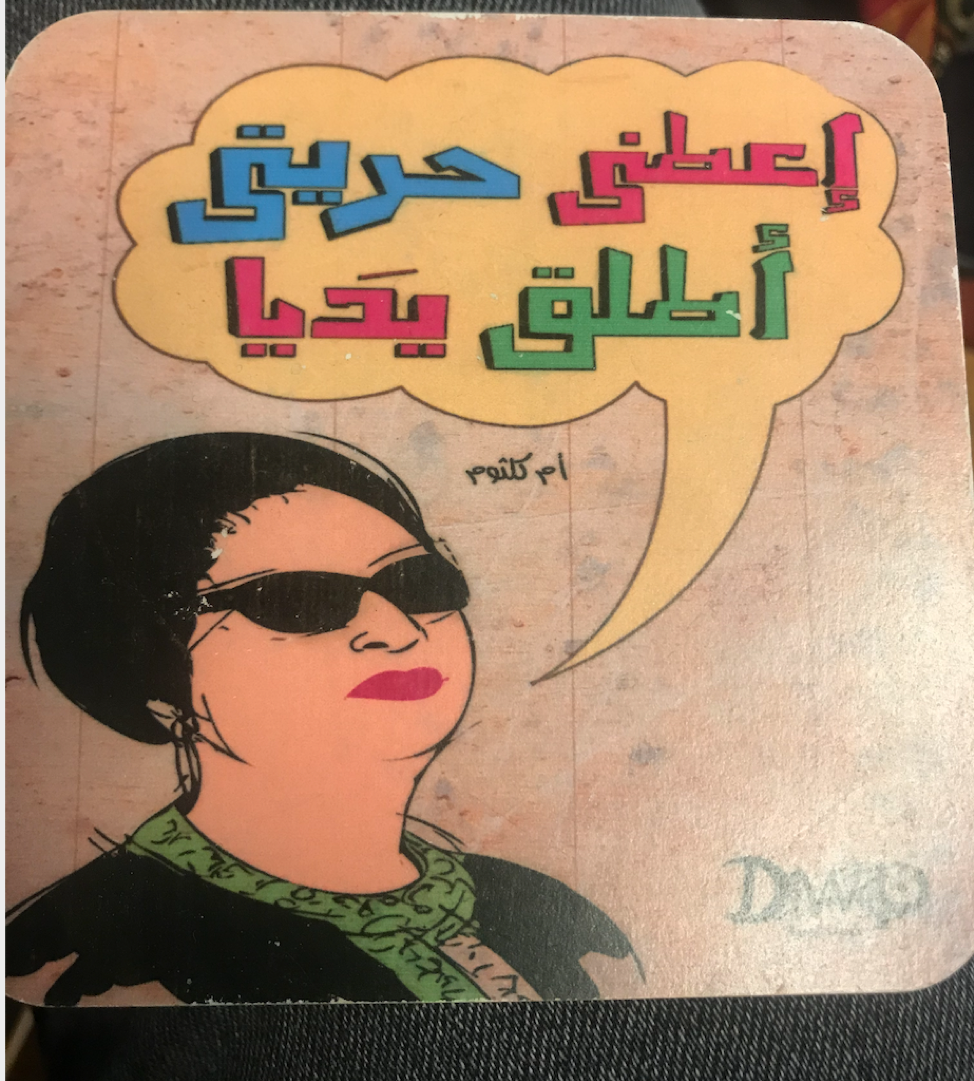

The people who pushed back against these notions of Umm Kulthum supremacy were elites, mostly academics. If you asked them, young people do not listen to Umm Kulthum. They commented on the pop art: the t-shirts, the necklaces, the coasters evoking Umm Kulthum. They told me this was a sure sign her star had fallen: this was pop art, popular because it was kitschy, not because of who it represented. Young people enjoy tokens to show who they want to be on their sleeves; it does not reflect who they are. Pop art is elitist. I’m sure these academics would have said the same thing of my Fairuz t-shirt from way back when.

To some extent, they’re right. The Umm Kulthum socks I bought a friend cost a pretty penny. The coaster I keep on my desk did not, but it symbolized elite culture all the same: a Cairene bookstore made them and bookstores can wear an elite glow that discourages people that do not belong. Coasters themselves are an elite idea, if you scrunch your eyes up slightly and take a step back. There are traps set around elitism and privilege and they are traps that are meant to correct, to move us towards a more equal society. I fall into those traps daily. But some forms of culture correct us. They remind us that the venues we privilege, the way we engage other human beings, and the cultures we can share all have consequences. My Umm Kulthum coaster reminds me of that, as it sits on my desk, Umm Kulthum’s face partly obscured by my tea cup. It’s also a reminder to switch to my Umm Kulthum playlist.

Sometimes, instead, the coaster also reminds me to switch to my Cairokee playlist, blatantly one of my favorite bands. Something of the woman who loved Fairuz because she crossed boundaries, blending funk and debke, loves the band for the same reason. They blend sha’abi, rock, hip-hop and more. The Egyptian people agree with me: their Kan Lak Ma’aya was the most popular song in Egypt the summer of 2019. It is this track I switch to when reminded by my coaster and with good reason: al Sitt lends the title lyric here and Cairokee sampled a lyric of her classic Ansak ya Salam. I listen to it when I’m writing my dissertation and I grin when I hear it in downtown Cairo booming out a microbus. Listening to it, even when not listening to Umm Kulthum directly, I submit to al Sitt, she who creeps into everything and makes it her own, she who will outlive me and does more than I – a wannabe intellectual – ever could for my homes and my peoples.

N.A. Mansour is a PhD candidate at Princeton University’s Department of Near Eastern Studies, where she is writing a dissertation on the transition between manuscript and print in Arabic-contexts. Her interests include Islamic studies, Arabic-language pop culture, and food.

Captions for Images: 1- Fairuz on a Graphic T-shirt (Photo Credit:JoBedu); 2- Umm Kulthum, 3- An amulet-style necklace featuring the lyrics of Umm Kulthum (Photo credit: N.A. Mansour).

Athar and the Boundless Multiplication of Relics | by Richard McGregor

The analytical model of popular versus elite culture seems to have outlived its usefulness, but perhaps some of what that model was trying to describe may be reclaimed and reframed in useful ways. Even if the structure of this binary is too loaded with assumptions about power and privilege, some of the phenomena it sought to represent nevertheless remain with us. I’m thinking here more specifically of the sense of uncontrolled multiplication of human culture; that is to say, human practices, ideas, and artifacts, which proliferate in unbounded but not random ways. This is the idea of a decentering and scattering of cultural agency, which was surely part of what the term “popular culture” was referencing.

It is this sense that drives the Islamic concept of athar (pl. āthār), whose most basic meaning is imprint or marker. The semantics of the term also have a temporal range, as in a ‘trace’ or ‘footprint’, both of which connect the present moment with the past. Hence an athar may be a material relic, serving as a tactile or visual bridge, or an oral tradition (hadith), a report passed down from the earliest days of Islam. Like footprints in the sand, which leave information for those who are attentive to them, both relics and hadith reports connect an evolving present to a sacred past.

It is this sense that drives the Islamic concept of athar (pl. āthār), whose most basic meaning is imprint or marker. The semantics of the term also have a temporal range, as in a ‘trace’ or ‘footprint’, both of which connect the present moment with the past. Hence an athar may be a material relic, serving as a tactile or visual bridge, or an oral tradition (hadith), a report passed down from the earliest days of Islam. Like footprints in the sand, which leave information for those who are attentive to them, both relics and hadith reports connect an evolving present to a sacred past.

Recalling the sense I evoked earlier of uncontrolled multiplication of religious culture, the connection between reports and relics is redoubled. Collecting, transmitting, and assessing hadith – and likewise the display, preservation, and provenance of relics – must seek in part to control the boundaries of such expressions. Not every object can be a relic, and not everything put forward as the words of the Prophet or his companions can be canonized as tradition. Thus, athar is both a continuity (an inheritance, a remainder) and a bounded or conditional proliferation.

Contacts and Impressions

One type of relic, rather evenly distributed across the medieval religious landscape, was that of clothing. Various personal items, including pieces of the Prophet’s shirt, were preserved in Cairo, many ultimately being housed at the Husayn shrine. The mantle and turban of the great saint Ahmad al-Badawi (d. 674/1276) are still displayed next to his tomb in Tanta. Medieval accounts make note of these objects, and their veneration. Footwear is another type of clothing with a long history as a relic. The earliest example on record – although one that seems to have had limited appeal – was the slippers of the Fatimid caliph al-Mansur (d. 341/953). His son cherished the Imam’s slippers and passed them down so later generations might benefit from the baraka.

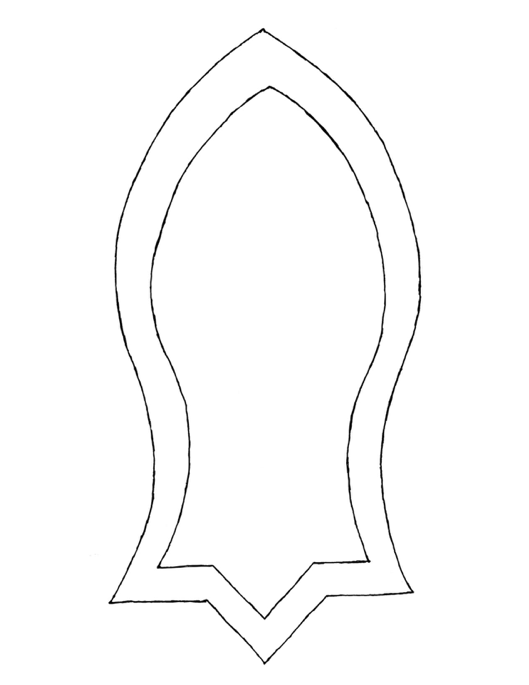

Holy footprints made several appearances on the devotional landscape of Mamluk Cairo. A set of important relics may be found at the tomb of Sultan Qa’itbay (d. 901/1496). Lying in the northern Qarafa cemetery, the sultan’s mosque and funerary complex houses two foot imprints in stone. One is attributed to the Prophet (figure 1) and the other to Abraham. The late seventeenth-century traveler al-Nabulusi visited the site twice, and described inscribed domes of silver and copper installed over the relics. The pious pilgrim recited from the Qur’an, and added supplicatory du‘a prayers while he kissed the imprints. The relics were so prized that even from the afterlife, Sultan Qa’itbay himself would jealously guard them. After a visit to the relics, the Ottoman Sultan Ahmad reportedly had them transferred to Istanbul. Later in a dream, in which Qa’itbay argued his case before the prophet Muhammad, it was made clear to the Ottoman Sultan that the relics must be returned to their rightful place in Cairo.[1]

Objects and Images

For narratives concerning the veneration of similar sandals, we move to Damascus. The Ayyubid ruler al-Malik Ashraf was particularly fond of this kind of relic. In 625/1228 he had a sandal relic installed in his newly completed madrasa, the Dar al-Hadith al-Ashrafiyya. This was not the only sandal in town however, and twelve years later the Madrasa Dammaghiyya would be founded, containing another sandal. Although Ashraf’s relic would be looted by the invading Turco-Mongol Tamerlane in 803/1401, it enjoyed a great deal of attention in the interim. An Andalusian traveler visiting the Ashrafiyya in 648/1285 mentioned the relic was housed in a niche to the left of the mihrab, with various texts of the Qur’an stored in a niche to the right. We are told that:

For narratives concerning the veneration of similar sandals, we move to Damascus. The Ayyubid ruler al-Malik Ashraf was particularly fond of this kind of relic. In 625/1228 he had a sandal relic installed in his newly completed madrasa, the Dar al-Hadith al-Ashrafiyya. This was not the only sandal in town however, and twelve years later the Madrasa Dammaghiyya would be founded, containing another sandal. Although Ashraf’s relic would be looted by the invading Turco-Mongol Tamerlane in 803/1401, it enjoyed a great deal of attention in the interim. An Andalusian traveler visiting the Ashrafiyya in 648/1285 mentioned the relic was housed in a niche to the left of the mihrab, with various texts of the Qur’an stored in a niche to the right. We are told that:

“The door of the niche was made of gold-colored brass, with three silken drapes (khilal) – green, red and yellow – hanging from it. The sandal rested in a special box made of ebony and held together by silver nails. A salaried custodian was in charge of displaying the sandal to the public twice a week – on Mondays and Thursdays. Visitors used to touch it, in the hope of acquiring some of its baraka.” [2]

Ashraf touted its virtues, and encouraged others to visit and gaze upon it. It could also go on the road; Ashraf had it sent to Ba’albek so that an elderly admirer could visit it. This was the grandmother of the historian al-Yunini who recorded the episode with pride in his Dhayl mir’at al-zaman. We do not have details on its transport or display, but perhaps portable reliquary practices were more common than we might think. Ashraf’s devotion to the relic endured to the end of his life. A report has come down from 635/1237, the year of his death, which describes him in the madrasa, taking the sandal in his hands, kissing it, placing it upon his eyes, and weeping. The prince left little doubt as to his own devotion to the object, and by implication the piety of the entire institution, which as a center for the study of hadith was a fitting place to store, display, and venerate the relic.

Ashraf had first come into contact with the relic thanks to Ibn al-Hadid – from a Damascene family well-known for their commerce in relics – who ceremonially introduced the relic to Ashraf, at which point he bared his head, and in joyful tears began to kiss the precious object and rub it against his face. A later traveler from the mid-fourteenth century describes the relic further in situ. He tells us there were two niches on the qibla wall of the madrasa. The one to the right of the mihrab contained copies of the Qur’an, while the one to the left housed the noble sandal. The sandal rested upon a stand, and its outline would be engraved upon an ebony tablet, which could be sprinkled with perfume and transferred to any devotee who kissed the outline of the sandal. Devotees visited the site on Mondays and Thursdays, when the relic was displayed and tracings could be made.

Although it disappeared with the onslaught of Tamerlane at the end of the fourteenth century, the ritual power of this relic had been well established. In addition to the madrasa centered veneration, it enjoyed a high-profile career in public protests. In 711/1312, when the merchants of Damascus were joined by the religious class in public demonstrations against the oppressive local governor, the Prophet’s shoe was brought out of the Ashrafiyya college. A mass of protestors assembled. Led by the preacher of the Umayyad mosque, Jalal al-Din al-Qaziruni, and carrying aloft the flags of the mosque, the ‘Uthmanic codex, and the sandal, the protestors marched together to confront the governor. Their protest however, was not well received. Jalal al-Din was violently arrested and dragged to the governor’s palace, while the sandal and the codex were thrown to the ground. News of this unrest alone was probably enough to get the governor dismissed, but for Muhammad ibn Qala’un, the Sultan back in Cairo, the insult to the codex and the sandal was unforgiveable, and he had the governor publicly humiliated and thrown in jail.

Making Pious Copies

As a miraculous relic, the sandal could be enlisted to help with personal afflictions beyond the political. An individual crisis would presumably have been behind many pilgrims’ visits to the Ashrafiyya sandal. But significantly, a rendering of the sandal could perform these services equally well. Stylized representations were copied one from the other in the thirteenth century, handed down along with their chains of transmitters, to guarantee their authenticity much as hadith reports from the Prophet and his companions were transmitted. [3] The great hadith commentator, al-Qastallani (d. 923/1517) repeated claims that tracings of the sandal would bring blessings to its owners, safeguard them from sedition, the machinations of their enemies, and the malevolence of the devil or the evil eye.

As a miraculous relic, the sandal could be enlisted to help with personal afflictions beyond the political. An individual crisis would presumably have been behind many pilgrims’ visits to the Ashrafiyya sandal. But significantly, a rendering of the sandal could perform these services equally well. Stylized representations were copied one from the other in the thirteenth century, handed down along with their chains of transmitters, to guarantee their authenticity much as hadith reports from the Prophet and his companions were transmitted. [3] The great hadith commentator, al-Qastallani (d. 923/1517) repeated claims that tracings of the sandal would bring blessings to its owners, safeguard them from sedition, the machinations of their enemies, and the malevolence of the devil or the evil eye.

The historian Ibn ‘Asakir describes a tracing of the sandal being placed on the site of pain on a suffering woman’s body, with miraculous results ensuing. These traced relics proliferated within Islamic book culture, appearing alongside poems and devotional descriptions of Muhammad and his virtues, all the while serving as tactile and tangible sites of relic interaction for its readers. Thus, these illustrations themselves became active relics. One modern scholar, Josef Meri, has noted how the tracing of the sandal in a manuscript copy of Ibn ‘Asakir’s work has been almost worn away by readers touching the image.

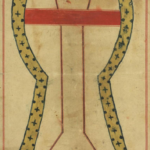

Another example, this one from the seventeenth century (figure 2), is typical, showing an embellished outline, along with the two leather straps. Often the straps are indicated simply by two circles, representing the holes made to hold them, which Muhammad used to secure the sandals to his feet. Al-Tirmidhi’s al-Shama’il al-Muhammadiyya provides details on the Prophet’s sandals, quoting material from the hadith and other early accounts. Despite the embellishments and stylized appearance, the precise dimensions of the tracing are crucial. As long as the dimensions are preserved, a limitless number of true copies can be generated.

The boundaries of this athar are only limited by the number of hands that take up the project of relic reproduction. A tracing made in 1848 – reproduced here by the Damascene scholar Issam Eido ( figure 3 )– consists of a thin double line. The contents of the book in which it appears make clear that despite its stylized reduction, the relic fully retains its power to deter misfortune. In this case of reproduction, the tracing appears in an eighteenth-century commentary on a seventeenth-century commentary on the famous panegyric poem Dala’il al-khayrat by the fifteen-century Sufi poet al-Jazuli. In this example, the line of reproductions spans from the fifteenth to the twenty-first century. In a 1901 printed copy, Yusuf al-Nabahani guarantees the accuracy of his copy by reassuring his reader that it has been photographically reproduced from an earlier seventeenth-century rendering in a book by al-Maqqari. Although al-Nabahani’s relic-as-tracing is mass produced, its miraculous and curative efficacy is not reduced.