Debates regarding all-encompassing transnational identities, and the historical circumstances which contributed to the construction of such imaginations, are gaining momentum as today’s ever-globalizing world becomes more interconnected in challenging long-standing sensibilities and allegiances at a faster pace. The new hybrid identities are taking shape in multi-cultural societies created by migrations and wars, identities difficult to define with reference to the traditional categories of the preceding century. This novel process also threatens – and has partially deconstructed – the political structures formed in the modern period, such as the nation-states of the Middle East. Exacerbated by mass scale migration, the process alters well-established Western political structures and ideals., It also increases the public support for racist, far-right movements. In contrast to the nineteenth and twentieth centuries, the identities such as “Muslim,” “Christian,” and “Liberal,” or a combination like “Liberal-Muslim,” live together in the same space. People with such seemingly contrasting identities share the same apartment-, university-, and office-space. Therefore, the requirement for the re-evaluation of the conventional wide-ranging definitions based on religious or secular contrasts imposes itself on the contemporary scholarship.

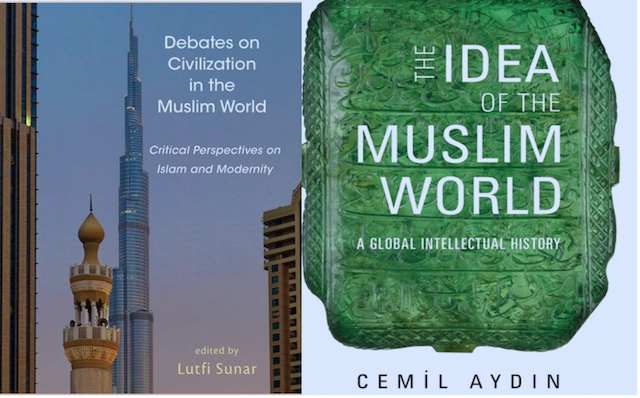

Two recent books, Cemil Aydın’s monograph The Idea of the Muslim World: A Global Intellectual History and Lütfi Sunar’s edited volume Debates on Civilization in the Muslim World: Critical Perspectives on Islam and Modernity, examine the rise of the ‘Muslim world’ and ‘Muslim civilization,’ concepts that seek to produce a response to the challenges created by the idea of ‘progress’ that is integral to modern thought. As insightfully discussed in both books, the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries by Enlightenment thinkers and their followers theorized and assumed there was a racial hierarchy, which then classified the industrialized societies as ‘developed civilization’ while identifying all the rest as the ‘backward’ peoples, who were at an ‘inferior level’ of historical progress.

Sunar’s volume includes fourteen chapters while Aydın’s book develops its argument across six chapters. The Muslim World is addressed to a general readership, while Debates on Civilization is written mainly for academics. Aydın adopts a ‘conceptual history’ approach While the chapters in Sunar’s edited volume endorse the theoretical debates of the sociologists and philosophers in the West and Islamic World. Both books, however, are crucial to understanding the constructive and ‘totalizing’ aspects of today’s commonly accepted terms describing Muslims.

“The Muslim World is addressed to a general readership, while Debates on Civilization is written mainly for academics. Aydın adopts a ‘conceptual history’ approach While the chapters in Sunar’s edited volume endorse the theoretical debates of the sociologists and philosophers in the West and Islamic World.”

The Roots of the Idea of Muslim Civilization

Muslim thinkers, in response, developed theories that accepted the contemporaneous ‘inferiority’ of their societies. And yet, they also claimed, invoking the glorious past of what they described as ‘the Muslim civilization,’ that this backwardness was not intrinsic to the nature of these communities. These were the endeavors to equalize the Muslims and their Western counterparts.

The two books complement each other in the topics they discuss. Aydın’s book focuses on the historical development of the concept of ‘an imagined global Muslim world’ and demonstrates its ‘imperial context.’ Aydin’s argument, seeks to correct existing scholarship’s view ofrepresentatives of ‘the Muslim unity’ or ‘Islamic civilization’ ideals as ‘anti-imperialists.’

“…the authors in Debates on Civilization in the Muslim World explain the epistemological background through which a ‘backward’ idea of the Muslim World as a lower stage of civilization was produced. Aydın’s The Idea of the Muslim World , however, analyzes the historical process through which the same idea was received by the Muslim intellectuals.”

The authors in Sunar’s edited volume, on the other hand, examine and criticize the ideas on ‘civilization’ developed by Muslim thinkers and criticize them for\ ‘unconsciously’ adopting the Western conception of a racial hierarchy. When read collectively, the authors in Debates on Civilization in the Muslim World explain the epistemological background through which a ‘backward’ idea of the Muslim World as a lower stage of civilization was produced. Aydın’s The Idea of the Muslim World , however, analyzes the historical process through which the same idea was received by the Muslim intellectuals. As highlighted by both studies, Muslim thinkers strongly opposed the idea that Islam was incapable of producing progress. These thinkers discussed how Islam produced a high-level civilization in the past and how it was liable to do so in the future by implicitly accepting the Western claims regarding the contemporaneous situation of their religion. By doing so, Aydın emphasizes, they implicitly approved the ‘imperial racialization of Islam’ in the nineteenth century by disregarding the diversity and cultural richness of the various Muslim societies.

Empire, Islam and Civilization

Aydın thoughtfully demonstrates in Chapters 3 and 4 the centrality of the Ottoman Empire to nineteenth-century and early twentieth-century debates on the ‘Muslim race’ or ‘Muslim civilization.’ As correctly highlighted by the author, the Empire was not seen by Muslims as the champion of Islam after its emergence as a world power. Likewise, as noted in Chapter 2, the Ottoman authorities were quite reluctant to support revolts by non-Ottoman Muslims and advised revolutionaries to remain loyal to their empires up to the last quarter of the nineteenth century, as they benefited from the continuity of the imperial world order.

Aydın thoughtfully demonstrates in Chapters 3 and 4 the centrality of the Ottoman Empire to nineteenth-century and early twentieth-century debates on the ‘Muslim race’ or ‘Muslim civilization.’ As correctly highlighted by the author, the Empire was not seen by Muslims as the champion of Islam after its emergence as a world power. Likewise, as noted in Chapter 2, the Ottoman authorities were quite reluctant to support revolts by non-Ottoman Muslims and advised revolutionaries to remain loyal to their empires up to the last quarter of the nineteenth century, as they benefited from the continuity of the imperial world order.

“Aydın thoughtfully demonstrates in Chapters 3 and 4 the centrality of the Ottoman Empire to nineteenth-century and early twentieth-century debates on the ‘Muslim race’ or ‘Muslim civilization.’ As correctly highlighted by the author, the Empire was not seen by Muslims as the champion of Islam after its emergence as a world power.”However, the situation changed in the age of high imperialism, as the interaction between non-Ottoman Muslims and the Empire increased and accusations against Muslims by Western Christians and missionaries began to influence the policies of the Western empires. In the writings of non-Ottoman Muslims, like Syed Ahmed Khan of India, the Ottoman Empire was presented as an example proving Muslims’ ability to be as ‘progressed’ as Westerners. Such an argument would facilitate their demands for equal treatment and justice within the framework of their empires. In addition, the spiritual authority of the caliph would strengthen their position within the British Empire. This was particularly the idea of British subjects, a population which comprised the largest Muslim polity in the world.

The Ottoman Empire gladly adopted this role from Abdulhamid II’s reign in the early 1880s , expecting to have British support in the inter-imperial competition, especially against Russia. Attempts at a reconciliation by the Ottoman government continued despite the British occupation of Egypt and conflicting interests in Arabia and the Gulf. However, with the outbreak of the First World War, a fundamental shift in the Ottoman definition of the ‘Muslim world’ occurred. . The imagined ideal of the Muslim World, which claimed to represent the Islamic civilization, had served as a tool to justify cooperation with the British Empire. When jihad was declared against France, Russia, and Great Britain, the conceptual framework was redefined and became a mobilizing discourse against the British, Russian and French forces.

Following the demise of the Ottoman Empire, prominent figures from Muslim countries congregated in Cairo to elect a new caliph. After this attempt failed, Aydın notes in Chapter 5, Muslim thinkers like Shakib Arslan and Rashid Rida made unsuccessful endeavors to find alliances among the leaders of the newly established Muslim states, such as Faisal of Iraq, Imam Yahia of Yemen, and Ibn Saud of Arabia. The decolonization process following the Second World War paved the way for the resurrection of Muslim internationalism and the concept of the Muslim civilization was widely discussed by the intellectuals of various Muslim countries.

“Sunar’s book includes informative chapters on the ideas of contemporary intellectuals such as Sayyid Qutb, Alija Izzetbegovic, İsmet Özel and Ali Shariati – prominent and influential figures who criticized the ‘Western civilization’ and emphasized the promise and the potential of ‘the Muslim virtues’ — as well as the critiques of those ‘anti-Westernisms’ by intellectuals like Hamid Dabashi.”

To complement this historical background, Sunar’s book includes informative chapters on the ideas of contemporary intellectuals such as Sayyid Qutb, Alija Izzetbegovic, İsmet Özel and Ali Shariati – prominent and influential figures who criticized the ‘Western civilization’ and emphasized the promise and the potential of ‘the Muslim virtues’ — as well as the critiques of those ‘anti-Westernisms’ by intellectuals like Hamid Dabashi. Other chapters in Sunar’s edited volume, containing details on the ideas of earlier intellectuals such as Jamal al-Din Afghani, enable us to connect early- and late-modern debates on the idea of a single Muslim world and civilization. These chapters also help the reader to better contextualize Muslim efforts to ‘revive’ Muslim civilization and become the ‘equals’ of the Western societies and states. These are important contributions to the existing scholarship because of the emphasis on the political nature of this global intellectual struggle.

Limitations

Although both volumes successfully place Muslims’ identity crisis and the search for a united identity over the last two centuries within the global intellectual context, both have certain limitations. First, both books are excessively focused on the interactions between Western philosophy and Muslim thinkers. The policies and official ideologies adopted by the leaders of Muslim states to westernize their countries might have been discussed in both books. They do not thoroughly elaborate on the Muslim practices (and the ideological background of these practices) inspired by the debates of civilization and Islam-West encounters. The ideas of ‘Muslim inferiority’ (Aydın) and ‘Muslim civilization’ (Sunar) shaped the acts of Muslim statesmen like Mustafa Kemal of Turkey and Habib Burgiba of Tunisia, who argued their goal was to elevate their respective nations to the level of western states.

“The policies and official ideologies adopted by the leaders of Muslim states to westernize their countries might have been discussed in both books. They do not thoroughly elaborate on the Muslim practices (and the ideological background of these practices) inspired by the debates of civilization and Islam-West encounters.”

The books do not analyze in detail the story of secularization in nations such as Turkey and Tunisia as part of the debates regarding ‘Muslim inferiority.’ If the publications had discussed Muslim movements of secular modernization, the arguments the authors put forward through the books would be more powerful, or the categorization of ‘Islam’ as the ‘West’s other’ would be more meaningful. Second, overlaps and repetitions between the chapters of Sunar’s edited volume may have been reduced by summarizing sections of some chapters –or excluding others from the volume.

Unanswered Questions

In addition to these shortcomings, the subjects discussed by both books raise new questions that are left unanswered. To what extent are we able to compare the modernization experiences of Muslim empires with the modernization experiences of the colonial ones? For instance, can we argue that the colonial racial hierarchy and other western practices were adopted by the Muslim empires? Did Muslim imperial rulers such as the Ottomans adopt the colonial mind-set and reflect it in their administrative/modernizing practices? Was there a racial hierarchy within the empire itself? To provide an example, Aydın interprets Ottoman intellectual Celal Nuri’s ideas about the debate with the following remarks: ‘whenever Nuri spoke of Muslims and the Muslim world, he had in mind not a community of believers but rather a racial and civilizational category comparable to the “black race” and the “yellow race”’ (111). However, there is no reference in either book to the intra-Muslim ‘racial hierarchy’ which may be considered as part of the debates on the ‘imagined Muslim world.’ These are crucial questions that warrant careful attention exactly because intra-Ottoman solidarity constituted an important aspect of the idea of Muslim solidarity and civilization.

“…can we argue that the colonial racial hierarchy and other western practices were adopted by the Muslim empires? Did Muslim imperial rulers such as the Ottomans adopt the colonial mind-set and reflect it in their administrative/modernizing practices? Was there a racial hierarchy within the empire itself?”

The impact of the racial discourse on the relations between the Muslim subjects of the Ottoman Empire could have been investigated within the ‘civilizational’ or ‘racialized’ framework that the books provide. The ‘racialized’ hierarchy was, to an extent, reflected in the Ottoman imperial discourse: the imperial authorities adopted colonial concepts in their description of mobile groups, using terms such as ‘savagery’ [vahşet] and ‘nomadism’ [bedavet]. Similarly, some of the imperial practices in distant regions like Tripoli could not be easily differentiated from the practices in the colonial repertoires. Accordingly, the racial discourse prevailed in the newly established Turkish nation-state’s discourse towards the Arabs. Kemalist intellectuals assumed a racial hierarchy between the ‘inferior Arabs’ and ‘Turks’ and situated themselves in a higher place in the Muslim racial hierarchy. Conversely, Arab nationalists like Muhammad Kurd Ali considered the period of Ottoman rule to be responsible for the backwardness of the Arabs and, like the Greeks, established a glorious civilization in the past. The Arab Nationalist class argued that the Arabs should ‘awaken’ and ‘beware of their potential’ to be as ‘developed’ as the Western nations, a discourse which continued following the demise of the Ottoman Empire.

Despite these problems, the books invaluably contribute to the existing literature and enable readers to rethink contemporary categories of identity that were constructed in different historical circumstances.