When Columbus landed in the Americas in 1492, he could never have anticipated the spectacle which the city of Chicago would orchestrate in his honor four hundred years later. The World’s Columbian Exposition was designed as both a celebration of the “discovery of America” by Christopher Columbus, and an enormous exposé on the latest technological, artistic, and architectural advances. The exposition officially began with a dedication ceremony on October 21, 1892. Even though, most of the buildings were partially constructed at that time. It opened to the public on May 1, 1893. The fairgrounds were constructed on 664 acres of land south of downtown Chicago and boasted a mile-long frontage on Lake Michigan (Rossen and Kaduck 1976, vii.).

The spirit of greatness of the Exposition of 1893, seemed from the very inception of the idea to permeate the whole body of gentlemen whose duty it was to prepare for the entire world a Fair that would in every way surpass anything heretofore undertaken by men (Smith 1893, 7). While one of the initial goals of this celebration in Chicago was to demonstrate the world’s material advances in arts and industries, intellectual and moral progress, having a powerful impact on human development was also recognized as an indispensable part of the exposition. Standing independently from the entertainment culture of the Midway Plaisance, the World’s Parliament of Religions represented the largest spiritual undertaking of the Columbian Exposition (Gerdan Williams 2008, 56).

*Norman Bolotin and Christine Laing, The World’s Columbian Exposition: The Chicago World’s Fair of 1893, Urbana: University of Illinois Press, 2002, p. 41.

“Here all nations are to meet in laudable emulation on the fields of art, science and industry, on the fields of research, invention and scholarship, and to learn the universal value of the discovery we commemorate; to learn, as could be learned in no other way, the nearness of man to man, the Fatherhood of God and the brotherhood of the human race. This, ladies and gentlemen, is the exalted purpose of the World’s Columbian Exposition. May it be fruitful of its aim, and of peace forever to all the nations of the earth” (Davis 1893, 140).

Such was the message given by George R. Davis, the director-general for the World’s Columbian Exposition of 1893, in the introductory address for the dedication ceremonies delivered in Chicago on October 21, 1892. The Exposition also witnessed efforts by other countries to present themselves on the world stage. One such case was presented by the Ottoman Empire.

The Turkish Building

In the World’s Columbian Exposition, the effort to maintain Ottoman identity as the only great Muslim power consisted of avoiding representations of the Empire as uncivilized on the international stage. For Sultan Abdulhamid II, forming exhibits that depicted the modern aspects of the empire would facilitate construction of a positive Ottoman portrait in the 1893 World’s Fair.

The Ottoman Exposition Building, which sat across the Fisheries Building was a copy of the Ahmet III Fountain, originally built in 1728 by Sultan Ahmet III in front of the Topkapı Palace in Istanbul. In this educational section of the exposition products manufactured in Turkey were exhibited (908). The Turkish Building and its exhibits were designed to try to dispel the pervasive image of Turkey as a nation of languorous men and women. Immediately upon entering the building, one was encountered by a huge torpedo, exploded by an electric cap, made in Constantinople. Standing at sixteen feet long, it looked like the offspring of the somnolent Asia. Display cases filled with mineral salts, Turkish coffee, and a stucco map of Constantinople accompanied the torpedo. A fire engine, proudly displayed in the center of the room, provided Constantinople’s best defense against the fires which frequently raged within the city. The Turkish building, which came next, was smaller. It was made of dark-colored Turkish woods, of pronounced Ottoman architecture, so it was suggestive of Oriental luxury. The remaining space between the Turkish building and the lagoon was filled with the magnificent Brazilian building.

When commenting on the Turkish Building, James Shepp, in Shepp’s World’s Fair Photographed, expressed his astonishment at the efficiency of the Turks. He offered a somewhat backhanded compliment at their ability to complete the exhibit on schedule:

“The Turkish Building in the foreign group is in all respects interesting. Strange as it may appear, this semi-oriental nation was the first to complete her exhibits at the Fair. Turkey has been called the “sick man of Europe,” but here, there is no evidence of decrepitude. The building is very odd and is made after the style of a fountain, erected by the Sultan Ahmad III., in front of the Mosque of St. Sophia in Constantinople. It is of dark wood, the exterior carving done by artists of Damascus, Syria. There is something about the structure that reminds one of a Tartar tent; on entering, there is a surprise in store for us. A huge torpedo, exploded by an electric cap made in Constantinople, is directly in front of the main portal. It is sixteen feet long and looks like anything but the offspring of the somnolent Orient. In the centre of the building there are several cases of mineral salts, and coffee for which Turkey is renowned. There are several line profile maps of Constantinople in stucco, and a picture of the great Mosque of St. Sophia done in human hair. The display of silks and jewelry is truly remarkable: though the Greeks in the Ottoman Empire, and not the Turks, may be accredited with their manufacture. The embroidery seen here is all done by hand: no machine enters into its fabrication. The women of the Turkish harems have ample time to spend upon needlework, and of this there is a large exhibit here. The most remarkable produ ction of feminine skill, however, is the work of three Armenian ladies (sisters). They have produced four books of music, all the notes embroidered so exquisitely that it would be very difficult to distinguish between them and the choicest productions of the printer s art. There is also an elaborately carved and inlaid wardrobe, a beautiful piece of work, unequalled elsewhere. We are almost tempted to laugh at the fire-engine and hose exhibited in the centre of the building, but we must remember that only a few years ago fires in Constantinople were left to the arbitrament of fate, and the poorest fire-engine is a great step in advance. When the question is Kismet or the fire brigade the latter will carry the palm invariably. There is a fine case of Grecian and Turkish books very well bound, and an assortment of rugs ranging from the manufactories of Smyrna to those of far-famed Samarcand” (482-84).

ction of feminine skill, however, is the work of three Armenian ladies (sisters). They have produced four books of music, all the notes embroidered so exquisitely that it would be very difficult to distinguish between them and the choicest productions of the printer s art. There is also an elaborately carved and inlaid wardrobe, a beautiful piece of work, unequalled elsewhere. We are almost tempted to laugh at the fire-engine and hose exhibited in the centre of the building, but we must remember that only a few years ago fires in Constantinople were left to the arbitrament of fate, and the poorest fire-engine is a great step in advance. When the question is Kismet or the fire brigade the latter will carry the palm invariably. There is a fine case of Grecian and Turkish books very well bound, and an assortment of rugs ranging from the manufactories of Smyrna to those of far-famed Samarcand” (482-84).

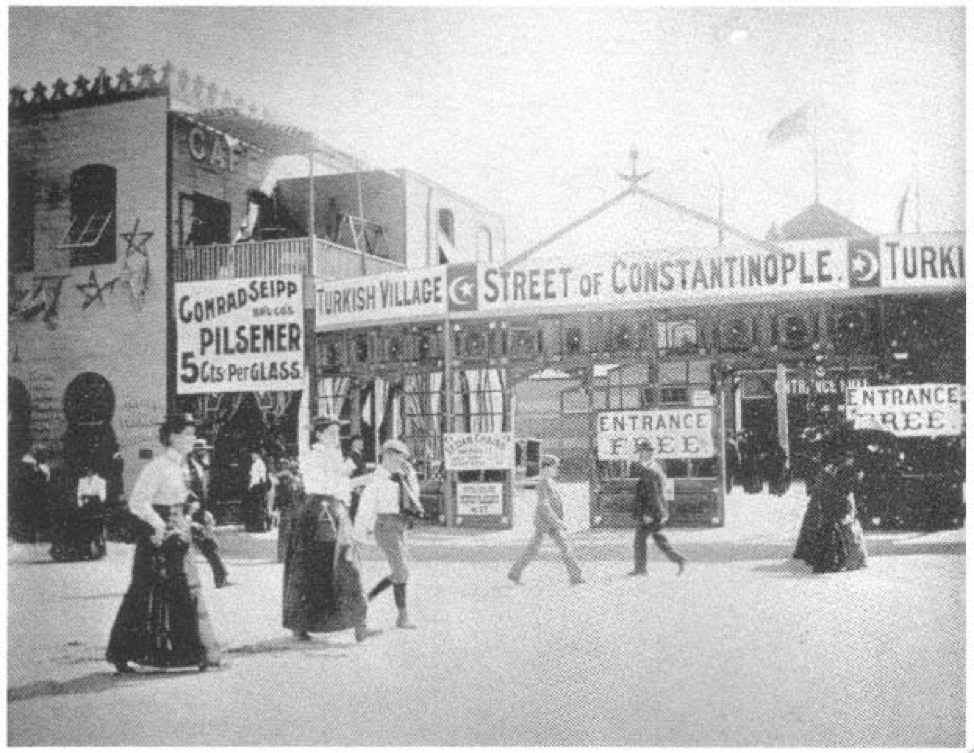

Turkish Village, The Midway Plaisance

The Midway Plaisance at the World’s Columbian Exposition also presented a fashion show of cultures, albeit in a slightly more irreverent manner. West of the central basin and reflecting its less serious function as a center of entertainment, the Midway stood in marked contrast to the gleaming white classical buildings of the “White City.”[1], Turkish Sultan Abdulhamid II quickly accepted the invitation of the U.S. president Benjamin Harrison to represent the Ottomans[2], as the fair was a good opportunity to portray the Ottomans with a positive image in the United States. Demanding a desirable location in the Fair, the Sublime Porte contracted the task of preparation to a commercial firm, Ilya Suhami Saadullah & Co., which was represented by concessionaire Robert Levy.

The Turkish Village in the Midway Plaisance included an imitation of one of the old streets in Constantinople. Its display originally was comprised of selections from Ottoman culture, such as luxurious pavilions, costly pieces of furniture and decoration, sedan bearers, a Persian tent, a bazaar with forty booths, a candy factory selling the most popular Oriental sweets, a refreshment pavilion, and a mosque erected by special permission of the Ottoman government (Bancroft 1893, 855-57). Highly concerned with its self-image at the World’s Fair of 1893, “…the Ottoman government intentionally sought to avoid objectionable—unregulated—displays of things oriental—from dancing girls to dervishes to wild Arab Bedouin” (Makdisi 2002, 768-96). As Selim Deringil stated, stringent conditions were laid down for the Turkish theatre, as “no plays injurious to the honor and modesty of Muslim women or damaging national honor and prestige” were to be performed in this exhibit (Deringil 1999, 155).

It was an open street, with booths along one side of it; and a covered bazaar, loaded with the spoils of the Sublime Porte. In the upper end of the street was a mosque, with real priests and religious rites, and a minaret, from the lofty balcony of which, at the hours of sunse

t, noon, and sunrise, a real Muezzin exhorted the faithful to remember Allah, and to give Him glory. The Turkish Village covered about one block. There were two theaters portraying scenes of Turkish life, customs, and Turks carrying sedan chairs.

Visitors were enticed to take another trip to the “Orient” by the women who beckoned from the open portiere at the Turkish Bazaar. Unlike the Turkish Building on the lagoon, the Turkish Village and Bazaar were primarily commercial ventures. The Turkish Village was composed of bazaars, theatres, temple of worship, and restaurants. The original Turkish Theatre, under the management of the Messrs. Maghgabhgab was very interesting, as a genuine performance of a Turkish drama was performed here. The play was interpreted throughout, so that persons visiting it had a thorough understanding of the plot of the play. The cost of the theatre was about $10,000 (Smith 1893, 96). Historian and photographer Shepp described it perfectly, as he wrote:

“Here we find that elaborate preparations have been made for our reception. The Turkish Government has taken a deep interest in this exhibit. We are surrounded on all sides by mosques and minarets. One might easily imagine himself on the banks of the Bosphorus. Turks dressed in their native costumes are to be seen along the street in Constantinople. Everything is as real as it could possibly be made. Bazaars may be found here in abundance, and there is ample opportunity for spending a dollar or two in curiosities.”

In his memories Ubeydullah Efendi describes the Turkish Village as follows:

“… Two things have caught my eyes in the Turkish Village. One of those was a panorama seen by the public including an interior appearance of St. Sophia, a street in Şehzadebaşı, the bridge in Tophane Street, the shore of the Dolmabahçe Palace and some more views. Apart from these there were also some pictures about the El- Aqsa Mosque in Jerusalem, and parts of Syria. In short ali were 18 pieces. The second one was the cotton candy…” (Alkan 1989, 1).

Turkish Mosque

In the Turkish village, along the Midway Plaisance, was a beautiful Mosque, the interior of which is shown in the picture below.[3] Ottoman mosque, a small fabrication of the Suleymaniye Mosque in Istanbul,[4] was inaugurated three days before the official opening day of the exposition (April 28, 1893), gathering all Muslims in Chicago for the performance of the Friday prayer. Every Muslim who came to this mosque for daily prayers was in fact evidence of the leadership of the Ottoman Caliphate over the various Muslim states and societies on the earth. There were many pious Muslims on the Expositi on grounds who would feel lost if they did not have a house of prayer to turn to twice or thrice a day. One of the photographers who visited the mosque said:

on grounds who would feel lost if they did not have a house of prayer to turn to twice or thrice a day. One of the photographers who visited the mosque said:

“Visitors are allowed to enter only when the hour of prayer is over, as the Mosque is not considered a show-place in the general sense. This building is a reproduction of one erected by the Sultan Selim, in Constantinople, and it is a great comfort to the three hundred Moslems who attend its pray. Nothing is omitted here that could possibly remind one of a Mosque in Turkey. At stated intervals the Muezzin ascends to the platform, just below the minaret, and calls loudly that the time for worship has come. There is a picture end of this article the heads of the men who are praying, are bowed toward the holy city of Mecca, as the prophet in the Koran ordains. To the left, we see the pulpit of the Imam, from which the holy writings are expounded to the faithful. Imam preach daily from just such a pulpit, There are no seats in Mohammedan Mosques. They, in this respect, resemble Greek churches. Within the Mosque in our picture, we find a great variety of interesting objects brought from the Orient, and dear to the hearts of the children of Islam. The Turk is, of all men, most religious; he eats, drinks, sleeps, and dresses by the Koran. Almost every action of his daily life is prescribed for him, and it is this which makes it so hard to convert him to Christianity; he is an abstainer from wines and all strong liquors and, though cruel to the races that he has conquered, he is possessed of a rare and winning courtesy to those of his own nation, and to strangers in whom he has confidence. The Sultan is supposed to be the head of the Church, as well as of the Empire, though even he must take advice from the Sheik ul-Islam, who is the legitimate expounder of Turkish law and custom. It is pleasant to see among us, Moslems practicing their religious rites without hindrance; we may learn from them to be true to our principles and duty” (Shepp and Shepp 1893, 500).

In The World’s Fair As Seen In One Hundred Day, Henry D. Northrop analyzes the time of prayer at a mosque in Chicago (1893, 687-88):

“When the 200 bandy-legged Turks, who wound up in this procession filed into the Turkish village, the mullioned windows of the tiny minaret far above were flung open. The dusky, clear cut forehead, the distended nostrils, the firm, even mouth of the Muezzin, Osin Bey, appeared. In the silence that his figure inspired, the weird prayer, with something of the sweetness of a Swiss song in its intonation, floated down upon the devout Muslims and the curious Americans. Then, without warning, the drummer broke loose again. They went up before the open doors of the mosque, beat a frenzied crescendo right about faced and stalked off, with the procession following. At this point the Second Regiment band appeared, and, much to the disgust of the Turks, began to play. Around the whole village, harem, bazar, office pavilion, mosque, and all went the procession. Then back to the mosque again. At this point a wild-eyed Moslem, robbed of the enrapturing music of his childhood, went over to the leader of the Second Regiment band and begged him to shut down. He didn’t succeed, and he went to the mosque sad-eyed and pensive, pulled his shoes off and dumped them into a big pile of long-toed footwear.” [5]

With all the rest of the Turks he slipped into the mosque and knelt down on the costly rugs. After all, real Turks were on their knees, all the imitation Turks who could rushed in as spectators. The shrine is a square booth, hung with rich tapestry. In this the muezzin stood. Behind him was a row of thirteen Mohammedans, acting as priests.

In a low voice the muezzin began the services. Turning suddenly, he recited a part of the ritual to the solemn thirteen. No sooner had they responded than a soprano exclamation of “Allah” came from every Turk present, and every forehead went to the floor. This ceremony was repeated several times and the mosque was dedicated.”

[1] The Ottoman government had a main Turkish Building situated among the national pavilions in the Jackson Park. There were also Ottoman displays in the specialized buildings of the White City: Several caiques, boats and sedan chairs in the Transportation Building, some quantity of agricultural produce from the Bursa region in the Agriculture Building, industrial products in the Manufactures and Liberal Arts Building, specimens of all kinds of wood in the Mines Building as well as books of Fatma Aliye Hanim in the Library of the Woman’s Building and Abdulhamid Albums depicting the modernization of the 19th century Ottoman Empire. See, Zeynep Celik, “Speaking Back to Orientalist Discourse at the World’s Columbian Exposition,” in Noble Dreams, Wicked Pleasures: Orientalism in America, 1870-1930, pp. 77, 83-84.

[2] In February 19, 1891, American Embassy in Istanbul presented the proclamation of invitation of President Benjamin Harrison (dated Dec. 24, 1890), the related Congress Act (dated April 25, 1890). for the presidential proclamation and the other material presented to the Ottoman State, BOA, İrade Meclis-i Mahsusa, 5194.

[3] Appendix on Interior of Turkish Mosque

[4] The construction of the mosque in Chicago was prescribed in the sixth article of the between Ottoman State and Sadullah Sihami Co., The mentioned article was saying that the mosque would be built on the area assigned to Ottoman State. this mosque would be serve Muslims present in the exposition and might also be visited by non-Muslims if Ottoman commissioners allow them to do so. BOA, Y. A-Hus., 58/33; Gültekin Yıldız, “Ottoman Participation in World’s Columbian Exposition-Chicago 1893”, Türklük Araştırmaları Dergisi, Mart 200), p. 161.

[5] Henry D. Northrop, The World’s Fair As Seen In One Hundred Days, Ariel Book Company, Philadelphia, 1893, pp. 687-88.