In late May 2021, with Gaza reeling in the wake of an extensive bombing campaign conducted by the Israeli military, the Islamic Resistance Movement (Harakat al-Muqawama al-Islamiyah in Arabic, or “Hamas”) held a festival in the north of the enclave commemorating its “martyrs” in the conflict, boasting an array of fighters garmented in professional military gear. Broadcast through Al-Jazeera’s Arabic television station, Hamas chief Yahya Sinwar was seen being escorted through an admiring crowd, while the military-men on display on the festival stage stand before a wide banner centred on the dome of Jerusalem’s Al-Aqsa Mosque—a centre-point in Palestinian national symbology—and flanked by the images of martyred soldiers, Palestinian flags, and the Movement’s infamous missiles.

Such Hamas festivals are far from exceptional in the organisation’s long history of posturing itself as the mantle-holder of armed resistance to Israeli occupation. This is facilitated largely by the fact that Gaza continues to live under blockade, as Hamas’ narrative of violent action continues to be supplied by a rolling reality of state and state-supported violence against Palestinian civilians.

What does stand out from a discursive point of view, however, is how Hamas increasingly deploys a professionalised militaristic style in its self-presentations to constituents, rather than focusing solely on established nationalistic or Islamic imagery as one would expect of an Islamic-nationalist front like Hamas. Key historical and theoretical questions thus emerge around how the verbal, visual, and ritual discourse of military-preparedness and violence-readiness creates political action and community, echoing against features of the temporal context: What does it mean for groups to present themselves as professionally capable of organised violence? What historical occurrences facilitate its appearance? What makes it useful as a fixture within political discourse, distinct from the usual appeals to nation, religion, and ethnicity?

To help answer these questions for the case of Hamas and to interrogate the idea across global space and time more generally, recourse will be sought in a number of comparable historical cases across the ummah, cases in which the signalling of one’s capability to inflict organised, disciplined violence obtains political utility. What emerges is a distinct pattern where military symbology and imagery of violence-readiness undergird the ways that groups distinguish themselves as obtaining the right to authority, creating (in Rodney Barker’s parlance) group identities of ruler and ruled, especially when the language of power has been so frequently spoken in the target context through violent means.

“What emerges is a distinct pattern where military symbology and imagery of violence-readiness undergird the ways that groups distinguish themselves as obtaining the right to authority, creating (in Rodney Barker’s parlance) group identities of ruler and ruled, especially when the language of power has been so frequently spoken in the target context through violent means.“

Further, in investigating the trend across the ummah, it is shown that in these scenarios, the impact of visual languages of violence and militarism can be quite reliably disentangled from ideas of religion in general, or any theological tradition of Islam in particular. Despite armed Muslim opposition groups obtaining a recurrent place in global discussions around the relationship between violence and religion, the cases outlined show how militaristic discourses do not rely entirely on religio-moral discourses in influencing audiences, despite the moral-spiritual impetus the application of Islamic tradition tends to imprint on political action, as per the work of James Piscatori and Dale Eickelman.

Militaristic discourse in practice across the Ummah

To begin with, Hamas’ display of military professionalism is steeped within Hamas’ nationalist interpretation of Islamic tradition, particularly around the theme of martyrdom, or istishhad. The aforementioned “victory” festival opened and closed with an acknowledgement of fighters who had died during the May bombardments. Speaking last in the procession, hardline Hamas politburo leader Fathi Hammad perhaps best encapsulates the core meanings underpinning this ideology, outlining in brief the religio-nationalist banner the Movement seeks for itself and the pillars it uses for self-sacralising and justifying armed violence:

from the esteemed North [Northern Gaza], to our people in the West Bank, in Jerusalem, in Sheikh Jarrah, in Jaffa, Acre, Kafr Kanna, and in Lod and Ramla, our greetings are to those who rise up against oppression, rise up against tyranny, rise up against the forces of Satan, rise up united under the banner of “No God but God” [the Islamic testament of faith], under the banner of Jerusalem, and under the banner of Al-Aqsa [mosque]…

If the ideological content and end is clear, what is more subtle are the potential rationales behind using military pomp as a means for instrumentalising this content and achieving this end. To be sure, it assists Hamas in terms of political competitiveness, monopolising the heroism of armed action in a space where it remains the only major Palestinian movement willing to use armed violence against Israel. But what the constituency may also see within the military posturing is a movement that is clearly distinct from the street by virtue of its professionalism, worthy of admiration given that its soldiers place themselves as sacrifices in harm’s way, and ultimately deserving of political leadership. Its militarism may obtain utility not just because it is “Islamic”, but because it is self-distinguishing.

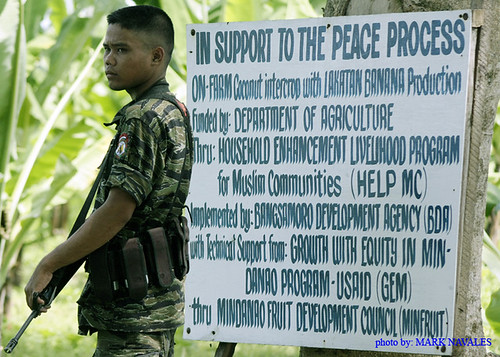

Turning to a recent video production from the Moro Islamic Liberation Front (MILF), the former rebel group now leading the Philippines’ Bangsamoro Autonomous Region in Muslim Mindanao (BARMM), surfaces this distinguishing, identity-building power of military symbology. Operating more like a latter-day armed resistance movement (when compared with Hamas) having diplomatically extracted autonomy from the Philippine Government after a decades-long history of armed struggle, the MILF does not boast of its ability to inflict organised violence, nor does it parade its armaments for viewers online. Rather, the January video uses the image of an aged combatant in Bangsamoro Islamic Armed Forces fatigues, ostensibly invisible to all the younger Bangsamoro around him despite his assumed history of liberationist combat. He is then only seen by a young child after the child tours the museum dedicated to the Moro history of struggle—the MILF outlet thus impresses onto the current generation of constituents the sacrificial importance of the older generation’s military struggle to the current state of relative peace.

The use of military imagery by the MILF therein differs greatly from that of Hamas and manages to sustain itself without adversarial overtures, but in examining what remains constant between the two cases a clearer picture emerges of the utility underlying this particular idea of military discourse. Primarily, both cases use the image of the ideologically committed soldier to elevate the status of the movement above that of the general constituency, in both contexts as the organisation/generation willing to sacrifice themselves in armed action against the adversary. Where in the case of Hamas, their ideologues celebrated the successes of their al-Qassam Brigades in fighting and dying for God and nation, the MILF has instead used allusions to the older generation’s martial commitments to command the constituency’s respect for the former MILF rebels now at the head of the regional government, “because what [they’ve] gone through should serve as a reminder that our hearts and minds stand firm and continue the struggle.” At the same time, while the aged MILF fighter’s uniform is emblazoned with the Moro-Islamic crescent moon and kris, the tenor of the video accords more with the memorialisation of historical struggle against oppression, rather than a Qur’anic or traditional command to commemorate warfare.

At a root level, then, one must ask: What is it about the capacity to inflict organised, armed violence that makes it a useful component of political discourse? Ingo Schroder and Bettina Schmidt, introducing their volume on violence as a subject of anthropological enquiry, note that the visualisations of violent symbolism are particularly useful for creating imaginaries of “internal solidarity and outside hostility”—violence attaches a severe, mortal urgency to the common questions of in- and out-group construction. At a more granular level, Lily Kong and Brenda Yeoh contend that the deployment of military pomp, whether through displays of equipment or the more refined parachuting skills of their infantry, allows Singapore’s National Day parades to reassure the public of the military’s defence capabilities, particularly throughout the latter half of the 20th Century where the shadow of military confrontation was front of mind for Singapore’s policymakers.

In light of this, the idea again finds a particularly pertinent manifestation within Blackamerican Muslim history and discourse which, like the context of the Palestinians and the Bangsamoro, interweaves with a memory steeped in a spirit of resistance and protest. The perennial Malcolm X reflects in his autobiography of an incident where disciplined members of the Nation of Islam presented themselves in “ranks-formation” before a Harlem police precinct building, pressuring local law enforcement to administer care to a man who was arrested and assaulted by officers. He took care to highlight that “[Harlem’s black people] never had seen any organization of black men take a firm stand as we were,” and reinforced this theme in reiterating what he had said to a police official confronting him: “our brothers were standing peacefully, disciplined perfectly, and harming no one. He told me those others, behind them, weren’t disciplined. I politely told him those others were his problem.” Malcolm X ends the chapter by illustrating the awe of the regular Harlem citizenry in witnessing the vanguard-like action of the Nation of Islam, an event that would soon springboard the group into the national spotlight.

Malcolm X captured with clarity how martial sensibilities can communicate political distinction-through-discipline while, paradoxically, acting as a beacon around which “regular” or “civilian” constituents may coalesce. What undergirded such an attitude, however, was also a drive towards what Sherman Jackson called “protest appropriation” in his analysis of the Nation of Islam’s countercultural forays under its founder, Elijah Muhammad. Although writing more about the cultures of refinement rather than military symbols, Jackson claimed that Muhammad, and his organisation more broadly, appropriated middle-class, genteel culture in order to deny white America total ownership of that dominant culture. According to Jackson, Muhammad was able to chart the path of an alternate, protest-centric means of becoming American by bridging the protest sprit of Blackamericans with the cultural practices, symbols, and artefacts that cumulatively defined what it meant to be American.

In this context, the activities Malcolm X described may be interpreted as an appropriation of the martial discipline so often employed by the machinery of a white American state against black communities. This time, rather than law enforcement, it would be the organized, genteel rank-and-file of the Fruit of Islam to set the tone of the encounter and the framework of protest. In other words, it is not only that Malcolm X’s followers were distinct through discipline, but also that they were contesting the realm of organised violence commonly monopolised by the police. Additionally, while Malcolm X in his autobiography was clear about the spiritual, Islamic distinction of the Nation at the time, his retelling of this particular encounter in Harlem was framed solidly around temporal organisation and tangible command of the public sphere.

Disaggregating Militaristic Discourse and Islamic Tradition

This article has, at a surface level, aspired to demonstrate how the militaristic posturing of specific non-state, avowedly Muslim actors is not necessarily dependent on Islamic tradition, and can be understood also from the lens of more general political symbolism and self-legitimation. The cases of Hamas, the MILF, and Blackamerican Islam are windows into the house of the idea that professional, martial symbology obtains utility through its distinguishing, legitimising power, particularly when deployed as an appropriative response to an adversary using the same mechanisms of organised violence. In all three cases, the political actors in question used military and/or disciplinary distinction to assume degrees of resistance/protest “stewardship” over their constituencies. Further, in all three cases, the political actors in question were pitted against adversaries who were using or who had used well-armed, formally-trained, professionally-ordered machineries of violence in controlling their respective communities—it thus becomes less surprising that an organisation like Hamas would respond in turn, and underscores ways in which threats of violence become animated through means other than direct references to religious edicts.

“In situations where ordinary life becomes shaped by military violence, there is potentially an increasing probability that discourses around control, authority, and resistance will also rely on appropriations of militaristic imagery.”

By exploring how this sensibility manifests across time and space, we begin to see more clearly how the imagery of professional, organised militarism is deeply interconnected with mechanisms of control and competition, and while this does not make it necessarily distinct from the tenor of oppositional politics in general, it does raise questions about what kinds of politics engender a turn to militaristic pomp, and the kinds of politics that such pomp reproduces. In situations where ordinary life becomes shaped by military violence, there is potentially an increasing probability that discourses around control, authority, and resistance will also rely on appropriations of militaristic imagery. The degree to which Islamic tradition is an inextricable driver of such military posturing should therefore, at the very least, be cast into doubt.

When, as in the Palestinian case, the military forces arrayed against your enclave are adorned with professional uniforms and high-tech implements of war, we may see why a group like Hamas adopts similar symbols, and engages in responsive violent acts, both to convince constituents of its resistance potency and to cement itself as a leader in the opposition space. While this does not preclude the emergence of non-militaristic discourses in the face of violent suppression—take Martin Luther King Jr, or the non-violent, anti-colonial Muridiyya jihad in Senegal, for example—it does shed indicative light on the levers shaping militarism, and the way its violent sensibilities tend to seep into different realms of political discourse, regardless of the theological or ideological threads woven into political practice by believers.

Miguel Galsim is an alumnus of the Centre for Arab and Islamic Studies at the Australian National University with an Honours degree in Middle Eastern and Central Asian Studies. His research interests centre the role of Islam within political discourse and foreign policy histories in the broader Islamic world, such as a published chapter on Hamas’ self-presentations in “The Islamic Nationalism of Hamas: Syncretism, Discourse, and Legitimacy” in Tristan Dunning’s Palestine: Past and Present (2019).