“Traditional Islam is not the replication of the positions of the ancients; it is to seek what they sought”.[1]

Introduction

During my doctoral research, an ethnography of a Dār al-‘Ulūm (madrasa) in Britain, the notion of tradition emerged as a significant analytical category. In popular discourse, tradition is viewed as something outdated, irrelevant, or stagnant, and is often contrasted with the modern. What I hope to show in this brief reflection is that tradition is in a state of transition and adaptation, due to both external shifts and internal reflection. Such shifts can benefit the students, or ṭālibs, in their overall learning experience. However, the flip side is that it runs the risk of unmooring them from their particular tradition, the maslak. Any change, then, comes at a cost. The question, then, is whether this change is worth the risk.

The “rope” of tradition

“What I hope to show in this brief reflection is that tradition is in a state of transition and adaptation, due to both external shifts and internal reflection. Such shifts can benefit the students, or ṭālibs, in their overall learning experience.“

During one dars (lesson) in madrasa, our teacher referred to a concise commentary of the Qur’ān written by the “Two Jalāls” (Jalālayn), Jalāl ad-Dīn, the Shāfi’ī al-Maḥallī (d. 864/1459) and his student al-Suyūtī (d. 1505/911) who supplemented his teacher’s work with his own commentary.[2] Here, sat in 21st century modern Britain, we were studying a 15th century text written in Egypt based on a revelation in 7th century Arabia, with a teacher who had studied in India. To guide the ṭālib between blind conformism and reasoned critique, he remarked on unthinkingly following one’s forefathers when it comes to accepting the message of the Prophet. This practice was in many ways from pre-Islamic times, which were widely referred to as the “days of ignorance” (ayyām-i jahilliyyah). God rebukes such people for they themselves “understood nothing and were not guided,” using the verb aql, which means to exercise one’s reason in understanding why one follows certain inherited practices or personalities.[3] We can see a strong rational discursive filter in approaching a Divinely revealed religion. In fact, the Arabic verb here in its original comes from ‘iqāl, which is a rope tied around a camel to prevent it from running away. The implication is that one ought to restrain their emotions and biases while exercising sound judgement when engaging with metaphysical truth.

But this linguistic reference gives an insight into tradition: it is a reasoned and restraining force, a rope by which each generation of believers are threaded to each other.[4] The current generation evaluates, assesses, and importantly, reasons with what they have received from the previous one without jettisoning core elements.[5] As Alasdair MacIntyre articulates, one is informed and circumscribed by inherited particularities.[6] As for the core of tradition, Sherman Jackson articulates that the doctrine of prophetic infallibility in Islam ensures that no one can “claim interpretive infallibility” except that of the “interpretive community.”[7] This refers to the ‘ulamā, or the “heirs of the Prophets”[8] whose understanding is rooted in authoritative sources and engagement with these sources based on time honoured principles of interpretation.

Lest one may reduce tradition to an intellectual activity, it must be embodied, primarily transmitted by means of ṣuḥba, a ṭālib-teacher relationship.[9] So, tradition, as I understand it thus far, is a reason-based discursive community of embodied carriers of knowledge whose roots are grounded with a metaphysical worldview.[10] This community then deploys this inheritance to guide their discourse in the present.

The syllabus, the Dars-i Nizāmī.

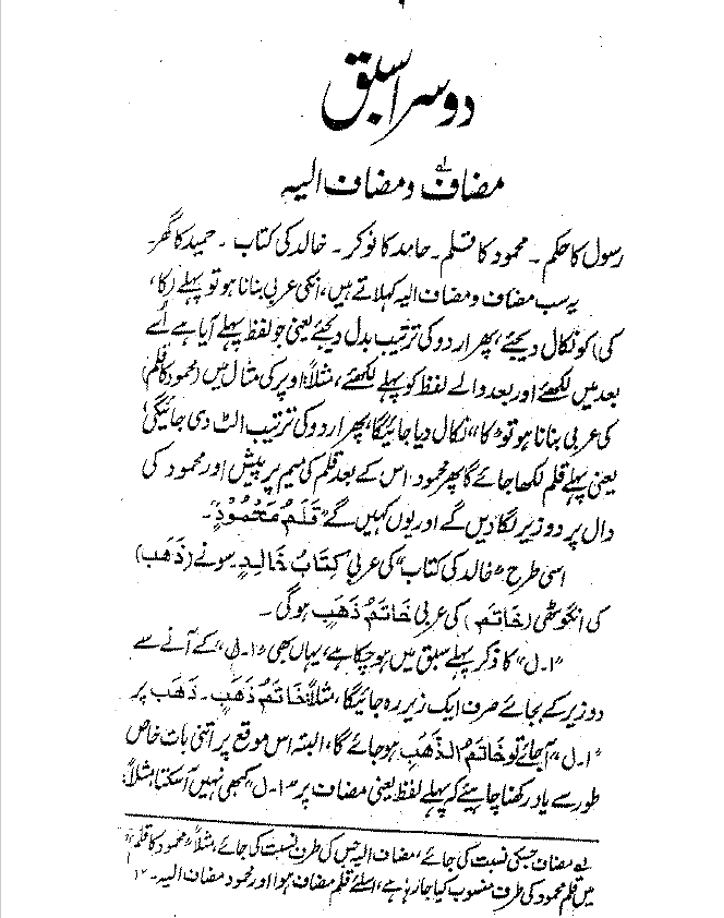

As an example of the above: the syllabus that is taught in many madrasas, the Dars-i Niẓāmī, has received criticism for being sacralised and averse to change. The texts studied in this program fall into two categories; the ancillary sciences (‘ulūm al-‘ālah) and the religious sciences (‘ūlūm al-Ṣhar‘iyyah). I will briefly engage with the former. The ancillary sciences are taught in the early years when the ṭālib masters the “tools” to unlock texts in advanced years. During my time as a ṭālib in 2003, there was a near absence of English in any of the texts; we learnt Arabic through the medium of Urdu. Here is a sample from a page of a text we studied and memorised on Arabic grammar titled “Das Sabaq” (Ten Lessons):

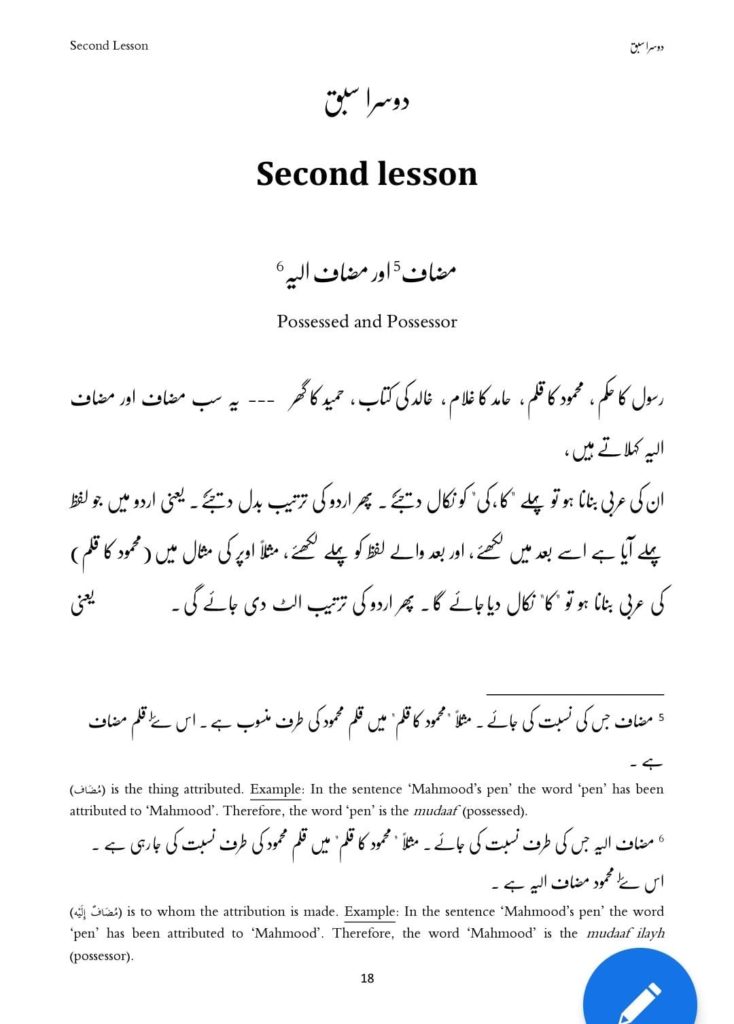

Here is the same page from an adapted text being taught when I returned ten years later as a researcher:

Returning over ten years later, I noted that the entire offering of the ancillary sciences had undergone change. While Urdu remained in some texts, portions had been incorporated with English while others had been replaced entirely. This ongoing adaptation has a tradition and history of its own; for instance, the texts we had studied in the early 2000s were themselves recent adaptations too. Before the Urdu texts, there were texts like naḥw-mīr, ṣarf mīr, mīzān munṣha‘ib and ṣarf bahā’ī, that were taught in Persian. In fact, Persian was the language of the Muslim East since the 1000’s and it remained this way at least until around 1750.[11] Even into the 19th century Iqbal was composing his moving poetry masterfully in both Urdu and Persian. Persian, as can be seen from texts such as the Pand-nāmā by Aṭṭār, Karīma by Sa’dī and Gulistān and Bostān by Sa’dī, played an important role in the cultivation of a moral subject, in poetry, adab, and in Sufism. It remained the lingua franca until the rise of Urdu which is a relatively modern phenomenon. Yet, due to the need of that time, texts in Persian underwent revision, adaptation, or replacement to Urdu.[12] Currently, with the diaspora in the West, Urdu itself is being marginalised to give to space to English.

“Now, returning as a researcher, I noticed the layout (as seen above) had also undergone change. Why did this happen, and who was behind it? In a short period of time—ten years—there had been a shift in the ancillary sciences.“

Now, returning as a researcher, I noticed the layout (as seen above) had also undergone change. Why did this happen, and who was behind it? In a short period of time—ten years—there had been a shift in the ancillary sciences. This change was undertaken by British-born ṭālibs who had become teachers in the madrasa. They instituted certain changes based on what they inherited and experienced, with the aim of ensuring their own ṭālibs would be able to access texts in the crucial years of mastering the Arabic language. Such teachers, who also teach compulsory secondary education at the madrasa, are currently merging pedagogical techniques with the Dars-i Niẓāmī. This reflective process takes place in consultation with senior teachers. As a result, they have set to work translating, adapting, and replacing texts. As one teacher put it, this movement had the dual effect of making teaching and learning more effective. He goes on to explain that nearly all the ṭālibs have a high degree of proficiency in the ancillary sciences as the medium of instruction is now English. As for Urdu, recognising its social and cultural capital, it is taught as a stand-alone subject, but is still an important part of the curriculum because the senior instructors who teach the religious sciences in the advanced years use Urdu as a language of instruction. Despite the relative marginalisation of Urdu, this should, one hopes, allow ṭālibs to contribute to the production of an Anglophone Islam that speaks to a new generation of Muslims, as Persian did, or Urdu still does.[13]

“However, one wonders what effect this will have on the ṭālibs link to the maslak, given that its worldview is overwhelmingly shaped through the language of Urdu.“

However, one wonders what effect this will have on the ṭālibs link to the maslak, given that its worldview is overwhelmingly shaped through the language of Urdu. Senior teachers, whose ṭālibs knowledge of Urdu is functional, are forced to simplify instruction in Urdu. Ṭālibs are less likely to read Urdu commentaries, which are a key component in gaining literacy in the Urdu classical inheritance. Many advanced readers who otherwise could make use of such commentaries are instead simply using Arabic commentaries, as demonstrated by the prolific growth of online British Islamic booksellers who cater primarily to an increasing number of voracious readers of Arabic commentaries. Persian provided a cultural ethic and aesthetic appeal, alongside a grounding in Sufism. Urdu maintained some of that through the writings of the akābir, the constellation of ‘ulamā who made up the Deobandi universe. What will the fading of this language in the local schools mean for the English-Arabic literate diaspora?

Conclusion

I hope by now that I have provided an illustration of how this tradition in Britain eludes a neat distinction between being traditional and modern. These adaptations undertaken from within the system itself challenge age-old characterisations of the Dars-i Niẓāmī—and Islamic education more broadly—as being sacralised and stagnant. These developments are being driven by external and internal needs. A tradition, then, is modern in that it must reflectively adapt to survive. The net result has led to an improvement in teaching and learning that is being led by a younger generation of British-born graduates. This is a tradition that has traversed continents yet has remained creative. However, this tradition has settled on a very different soil leading to questions around its rootedness to where it came from. There is a tension between being relevant and historically rooted, and it is the young ṭālibs who will determine its trajectory. In this way, they are no different to the ‘ulamā’ of a rich Islamic intellectual history who continue to adapt to remain relevant to the needs of society.[14]

Haroon Sidat is a post-doctoral researcher at the Centre for the Study of Islam in the UK at Cardiff University. His current research is a three-year project looking at the role British Imams play in society. His PhD was an ethnographic study of a British Dar al Uloom and is now being converted into a monograph. His other interests include Islamic law, Sufism, and Maturidi theology.

*I hope to publish a monograph of my research very soon.

Bibliography

Asad, Talal. “Thinking About Tradition, Religion, and Politics in Egypt Today.” Critical Inquiry 42 (2015): 166-214.

Bauer, Thomas. A Culture of Ambiguity: An Alternative History of Islam. Translated by Hinrich Biesterfeldt and Tricia Tunstall. New York: Columbia University Press, 2021.

Eaton, Richard M. India in the Persianate Age: 1000-1765. Penguin Books, 2019.

Green, Nile. The Persianate World: The Frontiers of a Eurasian Lingua Franca. Edited by Nile Green. California: University of California Press, 2019.

Hamdeh, Emad. Salafism and Traditionalism: Scholarly Authority in Modern Islam. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2021.

Harvey, Ramon. Transcendent God, Rational World: A Māturīdī Theology. Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press, 2021.

Ingram, Brannon. Revival from Below: The Deoband Movement and Global Islam. Oakland California: University of California Press, 2018.

Jackson, Sherman A. Islam and the Blackamerican: Looking toward the Third Resurrection. New York: Oxford University Press, 2005.

Laher, Suheil Ismail. “Re-Forming the Knot: Abdullah Al-Ghumari’s Iconoclastic Sunni Neo-Traditionalism.” Journal of College of Sharia and Islamic Studies 36, no. 1 (2018).

MacIntyre, Alasdair. Whose Justice? Which Rationality? South Bend: Notre Dame University Press, 1988.

Mathiesen, Kasper. “Anglo-American ‘Traditional Islam’ and Its Discourse of Orthodoxy.” Journal of Arabic and Islamic Studies 13, no. 0 (03/23 2017): 191-219.

Murad, Abdal Hakim. Commentary on the Eleventh Contentions. Quilliam Press Ltd, 2012.

Ware, Rudolph T. The Walking Qur’an: Islamic Education, Embodied Knowledge, and History in West Africa. University of North Carolina Press, 2014.

Zaman, Muhammad Qasim. “Tradition and Authority in Deobandi Madrasas of South Asia.” In Schooling Islam – the Culture and Politics of Modern Muslim Education, edited by Robert W. Hefner and Muhammad Qasim Zaman. Princeton: Princeton University Press 2007.

———. The Ulama in Contemporary Islam: Custodians of Change. Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2002.

[1] Abdal Hakim Murad, Commentary on the Eleventh Contentions (Quilliam Press Ltd, 2012), 34.

[2] See Ebrahim Moosa’s What Is a Madrasa (Chapel Hill: UNC Press, 2015), 120 for more on this text.

[3] Quran 2:170: “But when it is said to them, ‘Follow the message that God has sent down,’ they answer, ‘We follow the ways of our fathers.’ What! Even though their fathers understood nothing and were not guided?”

[4] For a discussion on the “rope of tradition,” see the Madrasa Discourses lecture by Ebrahim Moosa on reimagining a dynamic and living tradition: https://madrasadiscourses.nd.edu/module_attachments/2-3-1-reimagining-tradition/.

[5] As Zaman notes, “what is crucial is a shared engagement with works epitomising facets of the ulama’s scholarly learning and a certain agreement on the practices, the modes of discourse, associated with such engagement.” Muhammad Qasim Zaman, “Tradition and Authority in Deobandi Madrasas of South Asia,” in Schooling Islam – The Culture and Politics of Modern Muslim Education, ed. Robert W. Hefner and Muhammad Qasim Zaman (Princeton: Princeton University Press 2007), 64. See also Ramon Harvey, Transcendent God, Rational World: A Māturīdī Theology (Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press, 2021), 52-54.

[6] Alasdair MacIntyre, Whose Justice? Which Rationality? (South Bend: Notre Dame University Press, 1988), 360-61.

[7] Sherman A. Jackson, Islam and the Blackamerican: Looking Toward the Third Resurrection (New York: Oxford University Press, 2005), 7. See also Thomas Bauer, A Culture of Ambiguity: An Alternative History of Islam, trans. Hinrich Biesterfeldt and Tricia Tunstall (New York: Columbia University Press, 2021).

[8] Emad Hamdeh, Salafism and Traditionalism: Scholarly Authority in Modern Islam (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2021), 69.

[9] Talal Asad, among others, has attempted to show the embodied nature of tradition. See Talal Asad, “Thinking About Tradition, Religion, and Politics in Egypt Today,” Critical Inquiry 42 (2015). See also Rudolph T Ware, The Walking Qur’an: Islamic Education, Embodied Knowledge, and History in West Africa (University of North Carolina Press, 2014). For ṣuḥba, see Kasper Mathiesen, “Anglo-American ‘Traditional Islam’ and Its Discourse of Orthodoxy,” Journal of Arabic and Islamic Studies 13, no. 0 (03/23 2017): 204, https://doi.org/10.5617/jais.4633, https://journals.uio.no/JAIS/article/view/4633.

[10] Suheil Ismail Laher, “Re-Forming the Knot: Abdullah al-Ghumari’s Iconoclastic Sunni Neo-Traditionalism,” Journal of College of Sharia and Islamic Studies 36, no. 1 (2018)., notes that traditionalism is constituted of a “three-fold knot”: following a school of law (madhab), of theology, and of Sufism. My argument, in agreement with Ingram, is not that tradition is only “cerebral “or “discursive” but it is embodied too. Brannon Ingram, Revival From Below: The Deoband Movement and Global Islam (Oakland California: University of California Press, 2018), 21.

[11] Richard M Eaton, India in the Persianate Age: 1000-1765 (Penguin Books, 2019); Nile Green, The Persianate World: The Frontiers of a Eurasian Lingua Franca, ed. Nile Green (California: University of California Press, 2019).

[12] One key scholar involved in this project of reform was Maulana Mushtaq Ahmad Charthawali who wrote several books in Urdu which quickly became central to the madrasa curriculum. Of course, there has been an increased politicisation of Urdu too.

[13] One such example can be found in Abdul-Azim Ahmed’s engagement with Shahab Ahmed’s What is Islam. For more on this point see, https://medium.com/@AbdulAzim/mind-the-gap-the-textual-the-social-and-anglophone-islamin-shahab-ahmeds-2015-book-what-is-1e42b79e10ac

[14] See Muhammad Qasim Zaman, The Ulama in Contemporary Islam: Custodians of Change (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2002), 189.