In Charles Taylor’s magnum opus, A Secular Age, he makes a series of wonderful distinctions about the pre-modern and modern worlds. Among these is the idea that modernity entails a loss of enchantment, a move away from the old world inhabited by demons, angels, and magical creatures—toward a new reality guided by science, technology, and freedom of choice. One of the questions I was left with when reading this book many years ago was “what about those individuals who seek enchantment in their lives?” This is a question I try to answer in my most recent book, Buying Buddha, Selling Rumi: Orientalism and the Mystical Marketplace.

The search for enchantment in the modern world is often characterized by dilettantism—a meditation retreat in the desert surrounding Santa Fe, a vacation in Bali, a subscription to a New Age magazine. Orientalism often plays a role in these experiences and products, as seen in everything from Buddha bumper stickers to the mystical tourism that draws people to Turkey, India, and Morocco. Buying Buddha, Selling Rumi examines the ways in which moderns and their desire for enchantment is often situated in another desire—the desire to experience the East through mystical products and experiences.

“Buying Buddha, Selling Rumi examines the ways in which moderns and their desire for enchantment is often situated in another desire—the desire to experience the East through mystical products and experiences.”

Orientalism has always been a powerful intoxicant, first attracting European conquerors, then academics, writers, and artists. The paintings of artists like

Eugène Delacroix, Jean-Léon Gérôme and Frederick Arthur Bridgman suggest how enticing fantasies of the Orient and its inhabitants were at the height of Orientalism—popular subjects included harems with beautiful concubines, slave markets, and sultans. To some degree, these fantasies persist, in films, television, and political discourse, part of the large history of imagining the East through fictional characters. I documented many of these characters in my first book, Muslims in the Western Imagination (Oxford, 2015), focusing on the more frightening and monstrous depictions that populate the imaginaire in the West.

The Orientalist imagination has another side—more romantic than dangerous—focused on the promise of the East as a place of wisdom, enlightenment, and renewal. The mixing of images, ideas, and fantasies attached to these aspirational ideals are often jumbled together and confused, a key theme examined in my book that I call “muddled Orientalism.” As one example, Buddha and Rumi are often confused, with quotes from one ascribed to the other and with fabricated words and phrases attached to both individuals. The muddled quality of Orientalism also lends itself to the marketplace, where products, therapies, and experiences often combine or blur Hinduism, Buddhism, and Islam together. Mystical tourism, the business of selling enchantment, is popular in places like Bali and India, where visitors can experience the East in all of its diverse, exotic splendor. Mindfulness exercises, Ayurvedic cuisine, and Rumi readings are often found together in these places.

The Religious Marketplace and the Production of Mysticism

The commodification of religion is not new, as a glance at the past, at the trinkets, souvenirs, and mementos sold across Europe at the tombs of the Catholic cult of the saints demonstrate. Today, we find an incredible array of religious items for sale, some used in rituals, commemorations, and holidays. Hindu products used in the home provide one example of the ways in which the religious marketplace serves religious individuals. Statues of Hindu gods are often sold alongside food items and utensils in Indian and ethnic food markets, suggesting a fuzzy boundary between sacred and profane products.

“Mysticism, Incorporated, represents the seemingly endless choice of products, therapies, and experiences tied to the quest for spiritual growth through an engagement with the religious traditions of Hinduism, Buddhism, and Islam.”

In other cases, religions and their symbols are used to market a wide range of products that serve industries ranging from health and beauty, self-help, fitness, music, and wellness to domestic and international tourism. The consumers of many of these products and industries are heterogeneous. These individuals may be somewhat religious, identify as secular, or be classified as a “None”— the “spiritual but not religious” folks who often move from one religious tradition to another as part of a spiritual quest.

Mysticism, Incorporated, represents the seemingly endless choice of products, therapies, and experiences tied to the quest for spiritual growth through an engagement with the religious traditions of Hinduism, Buddhism, and Islam. Many of these products are connected to models of therapeutic wellness, self-improvement, and spiritual development. One example I point to in my book is the zafu associated with Zen sitting meditation, which comes in seven colors, different styles, and is marketed with various accoutrements—a bench, a prayer shawl, a meditation cloak, Buddha statues, and incense.

The products sold as part of Mysticism, Inc., often misrepresent the actual practice of the religious traditions they purport to be associated with. Tibetan medicinal products may be less associated with treating illness but instead are focused on problems like stress management. Like many other examples of the mystical marketplace, the appeal of the East lies in its promise to alleviate modernity’s problems. Ideas that the East is located in the past and is exotic and transformative are not just Orientalist; they reflect anxieties about the modern world and its stressors. Modern mysticism is salvific, promising an escape, a release, or a transformation that is available for purchase.

“The marketing of mysticism involves a translation project that erases complex religious teachings, texts, and rituals and replaces them with quick and easy systems for spiritual growth as well as fads like ‘Buddhist chic.’“

The marketing of mysticism involves a translation project that erases complex religious teachings, texts, and rituals and replaces them with quick and easy systems for spiritual growth as well as fads like “Buddhist chic.” This erasure often involves the promise of increased social capital, seen in everything from the prosperity gospel to mindfulness exercises focused on financial success. Modern mysticism is also associated with style, seen in companies like Prana that capitalize on the appeal of the East. Mystical fashion includes the styles and textiles of the East, which in the past included Japanese fashion and today often focuses on the kurta, caftan, and tunic. Subsets of mystical seekers also have their own distinct styles, or costumes. Foreign residents of Morocco have been known to adopt a “Riad” style. The American and European female white migrants who reside in Bali a distinct type of dress that features light colored, baggy pants, and made from a natural fiber like cotton or hemp. These women represent a lucrative sector of Mysticism, Inc.—the mystical tourist.

Mystical Tourism

Mystical tourism has great appeal for consumers looking for a vacation experience that focuses on mysticism. The Orient, as is the case for much of modern mysticism, is often marketed as the prime location for these holidays. Bali, India, Nepal, and Morocco, among other locales, are billed as exotic and transformative for the body and soul. One interesting case I describe in my book comes from Thailand, where a tourism ad features a robot who is transformed into a human, restored to his true self by the mystical powers located in the East.

“The yoga, meditation, and Sufi retreats identified in my book are examples of heterotopias that exist somewhere—in the past, in the imagination, and in the desires of the consumer.”

Heterotopias are often understood as sites of difference that offer an escape from reality, or in the case of the mystical tourist, an escape from Western modernity. Michel Foucalt described utopias not as real places but as the hopeful projections of perfect societies. In contrast, heterotopias are real. The yoga, meditation, and Sufi retreats identified in my book are examples of heterotopias that exist somewhere—in the past, in the imagination, and in the desires of the consumer. They are reimagined and recreated for the mystical tourist, in some cases with great success. The wellness resorts found on Bali’s coastlines and in the artist’s colony of Ubud demonstrate the clever marketing that is part of mystical tourism, featuring names like Blooming Lotus Yoga Spa. The people of Bali are also identified as centers of mystical (and sensual) power, examples of a “mystic power” where bodies are salvific. Primitivity is often a central part of a presentation of cultural authenticity that is part of mystical tourism’s marketing strategy.

Mystical tourism can also be found closer to home in places like Iona and Glastonbury, so-called “thin spaces” where the boundaries between light and dark, the dead and the living, and the present and the past are blurred. Iona is focused on the Celtic mysticism of early Christianity. In the case of Glastonbury, a Christian past is complicated by a number of other religious traditions. Hinduism and Buddhism are imposed on the British landscape through its status as a “karmic cluster” and a “site of Chakras.” An example of muddled Orientalism, Glastonbury also features a number of Sufi connections, including the presence of a Sufi store and a history of at least one Sufi order naming it the spiritual center of Britain.

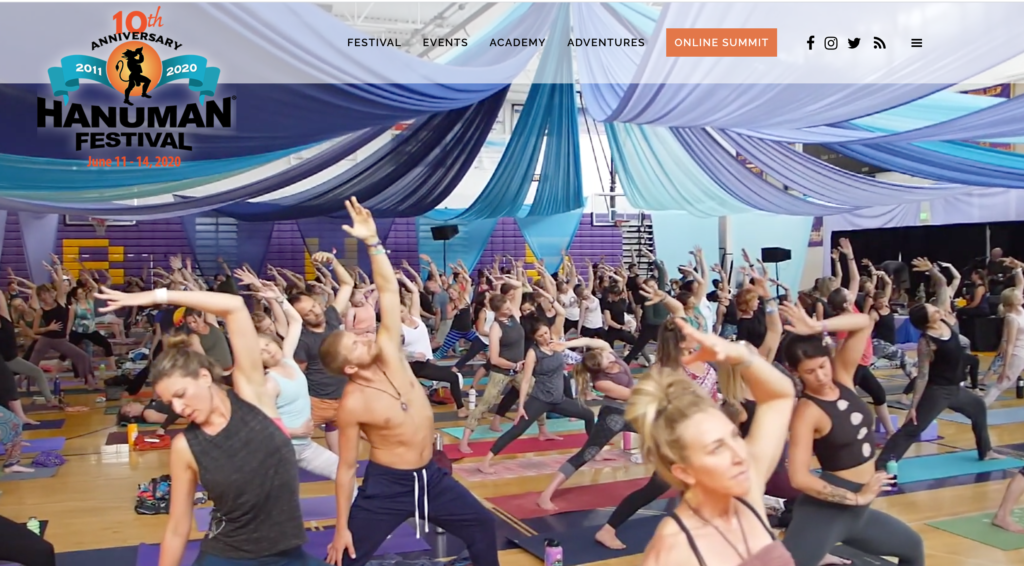

Tribe communities provide other examples of muddled Orientalism and its role in the mystical marketplace. These groups of people are typically associated with New Age, mystical, or spiritual movements and are mostly populated by white, affluent participants. The members of the California community called Full Circle consider themselves part of a tribe, as do the attendees of event tribalism. The Hanuman Festival and Burning Man are two examples of these events, characterized by what anthropologists have called “soft tribalism,” which includes particular styles of dress (or costuming), performances, and products.

The East plays a dominant role at these events. Hanuman Festival’s 2018 website featured a section titled “Our Tribe,” listing sponsoring corporations like Prana and Bhakti Chai that incorporate symbols like the lotus flower or mandala in their branding. An overwhelmingly white tribe event, most of its participants and teachers are white. According to my study, in one year only 10 percent of the teachers at the Hanuman Festivals were non-white, and only one was African-American. The commodification of Hinduism, Buddhism, and Islam are most apparent in the so-called “Community Village,” an outdoor shopping mall featuring items like yoga wear, candles, meditation aids, and Rumi quotes. Burning Man is not focused on yoga, but on the annual burning of a statue—a ritual that is the culmination of a week of performance art, costuming, and the installation of enormous structures made of natural materials. These structures, which includes a number of temples and a Sufi Slide, reflect a pronounced interest in the East. Temples are often dedicated to Hindu and Buddhist gods, and in 2017 one of the art installations featured a quote falsely attributed to Rumi in large, neon words. Participants also congregate in camps, including the Buddha Camp, which one year included activities ranging from Buddhist chanting to naked espresso gatherings.

Mysticism and Hollywood

Many products, therapies, holidays, and tribe events are connected to the search for enchantment and mystical experiences. Often identified with three major religious traditions—Hinduism, Buddhism, and Islam—these are all sectors of the mystical marketplace. Entertainment is another part of this marketplace that deserves our attention. In my book, I chose to look at two cases—the television show Lost and the Star Wars films. These visual narratives feature heroes, villains, magical powers, and mystical themes, and also include tropes, imagery, and language from the East.

Lost focuses on the survivors of a plane crash on a seemingly deserted island. The mystification of time plays a major role in the series, as do mystical experiences, Eastern imagery, and words. The island is eventually revealed to be the site of a government project called the Dharma Initiative, which involves strange creatures such as the polar bears who terrify the castaways and a doomsday shelter. One of the Dharma Initiative’s stations is called The Temple, led by an individual named Dogen, the name of a thirteenth-century Buddhist thinker. The megalithic statues that appear on the beach are reminiscent of ancient Egypt. Time is the most central religious concept, with the plotlines revolving around time cycles reminiscent of the Hindu and Buddhist circle of birth, death, and rebirth—samsara. The main characters, especially Jack, struggle with their memories of the dead and with mystical visions and experiences. In the end, Jack dies alone on the island in an emotional scene interspersed with a reunion with his castmates at a church of all religions. He enters the church only when he has freed himself from the past, his regrets and mistakes, and is at peace. Jack’s character arc is the mystical quest—he becomes a fully realized person once he has let go and accepted the world as it is, a key teaching in many traditions including Buddhism and Islam.

Star Wars is also a mythical mash-up of different religious traditions and mystical themes. The Force is a mythical concept, likely inspired by George Lucas’s own interest in religion, mythology, and mysticism that includes a study of Joseph Campbell’s work. Both material and ethereal, the Force is something like the mystical concept of God—one cannot see it, but they can feel it at certain moments. The influence of Buddhism on Star Wars is seen in the Jedi fraternity, likely inspired by the Japanese jidaigeki.

“The influence of Buddhism on Star Wars is seen in the Jedi fraternity, likely inspired by the Japanese jidaigeki.“Additionally, there is the celibacy of the Jedi, the ego as the source of fear and suffering, and the Force as a possible allusion to prana, which also flows through the universe and surrounds us. Messianic themes also abound in the films, linked to a number of traditions including the mahdi in Islam. Early drafts of the script for the first film included words like Kiber (after the Khyber Pass in Afghanistan) and Asla and Bendu (Persian names). Islamic imagery includes the planet of Tatooine, the use of veiling by everyone from Princess Leia to Rey, and Jyn Erso’s self-sacrifice in Rogue One, making her a shahid (righteous martyr) for the cause of justice. Luke and Obi-Wan Kenobi may be Buddhist siddhus (monks), or Sufi shaykhs, representing a long lineage (silsila) that continues when Luke trains Rey.

Conclusion

For many people, the East represents a place of magical promise that provides an escape from the world of disenchantment. The mystical marketplace offers products, but also communities and experiences, that rely on a commodified branding of Orientalism. Modern mysticism often obfuscates or erases the religious traditions on which it, in its many forms, rely. Other pieces of this story are told in my book, but I hope that this essay provides a portrait of the role of the East in modern mysticism, the religious marketplace, and the ways in which the imagination creates new religious worlds for people seeking meaning in their lives.

Sophia Rose Arjana is Associate Professor of Religious Studies at Western Kentucky University. She has published four books: Muslims in the Western Imagination (Oxford, 2015), Pilgrimage in Islam: Traditional and Modern Practices (Oneworld, 2017), Veiled Superheroes: Islam, Feminism, and Popular Culture (Lexington, 2017), and Buying Buddha, Selling Rumi: Mysticism and the Mystical Marketplace (Oneworld, 2020). Her next book examines gender, material religion, and ritual in Indonesia and is titled The Mosque with the Thatched Roof.