Ottoman Sufis were often criticized for engaging in bidʿa or innovative interpretations of Islamic texts by their orthodox opponents, such as the Qāḍīzādeh ʿulamā’. In their writings, members of the Qāḍīzādeh ʿulamā’ subjected Sufi treatises to a thorough investigation, searching for any divergences from what they considered the correct interpretation of the Qur’an and Hadith. They objected to several Sufi rituals, doctrines and concepts which they argued made no reference to the traditional sources. It was rare, however, that Sufis would discredit the texts of their own brethren. This essay charts the controversies that erupted not only between Orthodox ʿulamā’ and Sufis, but also between Mevlevīs themselves, because of Ismāʿīl Rusūkhī Anqarawī’s (d. 1631) commentary (sharḥ) on “Book Seven” of Rūmī’s (d. 1273) Mathnawī, which was considered apocryphal by the majority of Mevlevīs who believed Rūmī’s book consisted of six books. I will examine how a central Mevlevī text caused controversy among leading seventeenth-century Ottoman intellectuals and turned a scholarly debate among Sufis into a much broader religio-political clash between Sufis and ʿulamā’.

“This essay charts the controversies that erupted not only between Orthodox ʿulamā’ and Sufis, but also between Mevlevīs themselves, because of Ismāʿīl Rusūkhī Anqarawī’s (d. 1631) commentary (sharḥ) on “Book Seven” of Rūmī’s (d. 1273) Mathnawī, which was considered apocryphal by the majority of Mevlevīs who believed Rūmī’s book consisted of six books. “

Sufis vs. ʿUlamā’

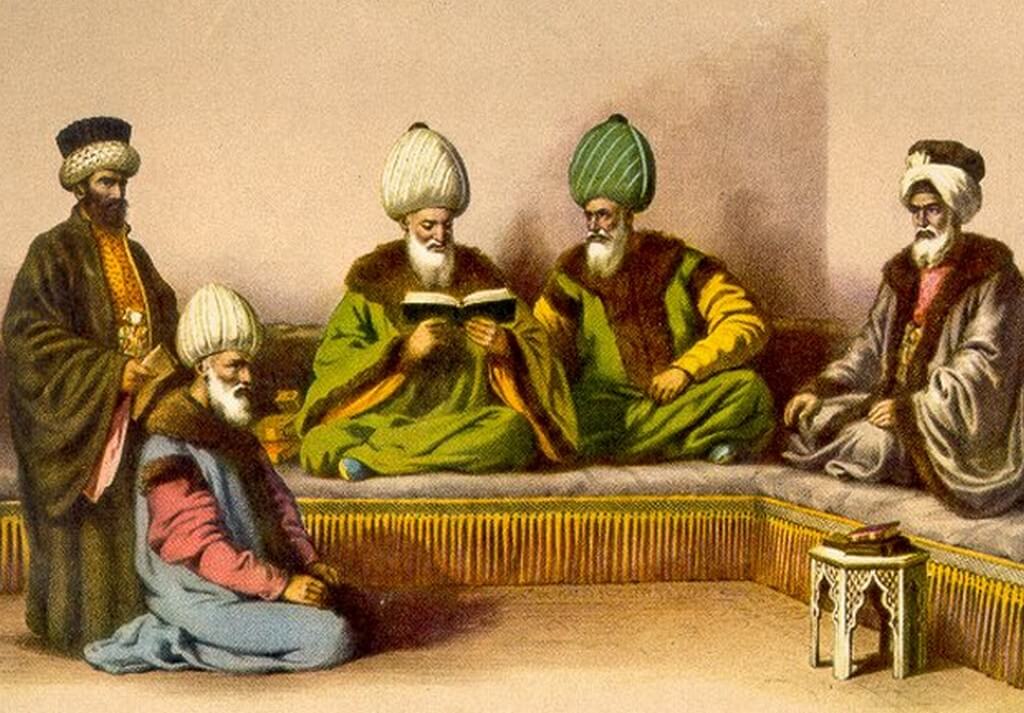

Among the influential groups in the Ottoman state were the Sufis, who organized themselves into various orders (ṭarīqat). Sufis not only acted as spiritual leaders for the masses, but also sometimes served as their political leaders. These Ottoman Sufis produced a rich literature known for its mystical approach to the Islamic sciences of Qur’anic exegesis (tafsīr) and Hadith, in addition to commentaries and translations of classical Sufi texts into Turkish. Sufis exercised an immense power over the social, political and cultural life of the public and rulers alike. Due to the popularity of Sufism among the masses, Sufi shaykhs benefited greatly from the Sultans’ patronage and this ensured that they remained loyal to the rulers. Sufi leaders thus helped in the maintenance of order and stability among the general population.

However, the Sufis’ approach to Islam and their way of presenting Islamic principles made them targets for criticism by the ʿulamā’. The relationship between the Ottoman state, Sufis and the ʿulamā’ began to change from about the mid-sixteenth century onward. During the seventeenth century, there was a major decline in the madrasa system. By the late sixteenth century, there was an obvious change in the attitude of the ‘ulamā’ towards learning. They had turned against subjects such as mathematics, geometry and medicine, and, as a result of that, the curriculum of the madrasa began to change.[1] The elimination of scientific and philosophical texts reflected the wish of Ottoman ‘ulamā’ to concentrate more on law. This process, according to Kātip Çelebi, marked the end of intellectual development and the beginning of stagnation in the Ottoman ‘ilmiyye.[2] At the same time, an increase in Sufi activities earned them the enmity of a new group of scholars who were to form the major opposition to the Sufis and who were militant enough to make a clash with the Sufis inevitable. This opposing group consisted of a number of preachers inspired by the teachings of Qāḍīzādeh Mehmed (d. 1635), who considered some practices and beliefs of the Sufis to be uncanonical, innovatory and heretical.[3] The Qāḍīzādeli family was popular and influential in the palace; its leaders were extremely vigilant in observing the rules of faith and punctilious in their ritual observances.[4]

“During the mid-sixteenth century and at the beginning of the seventeenth century, there was intense debate amongst ʿulamā’ concerning the legality or illegality of certain contemporary issues such as the usage of tobacco and coffee. Debates on this widespread popular practices gave scholars a platform to also express their condemnation of Sufi practices such as music, spiritual dance/whirling (samā’), meditation (dhikr) and rituals at Sufi tombs. Many regarded such practices as innovatory and irreligious.[5]“

During the mid-sixteenth century and at the beginning of the seventeenth century, there was intense debate amongst ʿulamā’ concerning the legality or illegality of certain contemporary issues such as the usage of tobacco and coffee. Debates on this widespread popular practices gave scholars a platform to also express their condemnation of Sufi practices such as music, spiritual dance/whirling (samā’), meditation (dhikr) and rituals at Sufi tombs. Many regarded such practices as innovatory and irreligious.[5]

As reformists dedicated to bringing about changes in society in accordance with the Qur’an and sunna, the Qāḍīzādeh felt it was a religious duty to prevent the Sufis from pursuing these practices. Mevlevī and Khalwatī/Hhalvetī[6] Sufis, who had assumed higher positions in the government, were particular targets. The Qāḍīzādeh were vehemently critical of the scholarship produced by eminent Sufi masters of the age, among them ʿAbd al-Majīd Sīvāsī (d. 1635), ʿAzīz Maḥmūd Hudā’ī (d. 1628), Nīyāzī al-Miṣrī (d. 1694) and Ismāʿīl Rusūkhī Anqarawī.[7] The Qāḍīzādeh’s criticism focused on what was seen as the Sufis’ innovative approach to commentating on or interpreting Islamic sources.

The Mevlevī Order

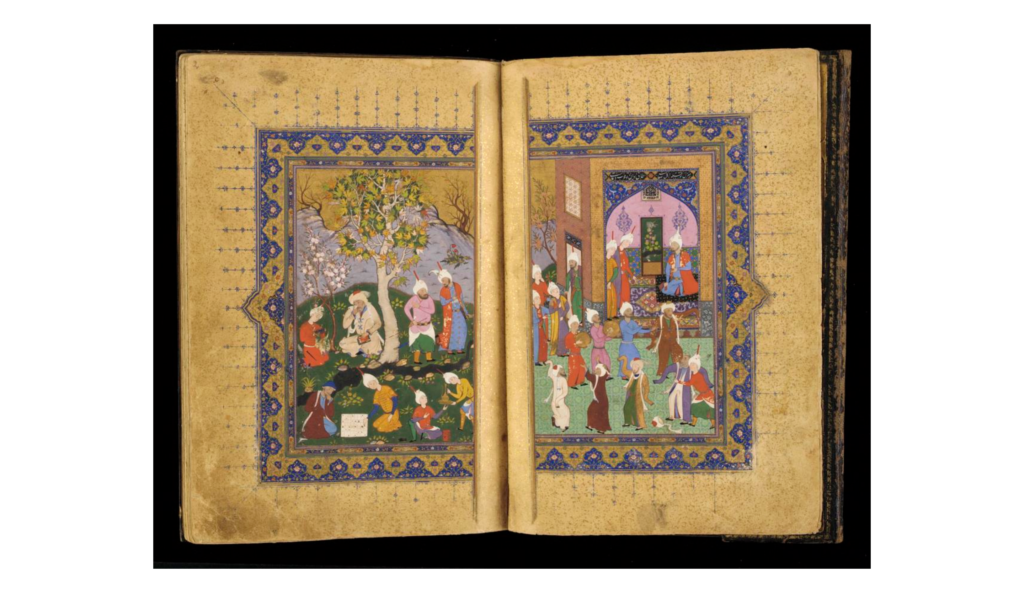

The Qāḍīzādeh movement strongly criticized the Mevlevīs despite the fact that the Mevlevīs had made a major contribution to Ottoman literature and poetry through their teaching of the Persian language and translation of mystic poetry.[8] They also came to be associated with the cultural elite in Ottoman society.[9] Indeed, the Mevlevī Order, which “was founded in 1273 by Jalāl al-Dīn Rūmī’s followers after his death, particularly his son, Sulṭān Valad,”[10] was well established in the Ottoman Empire and many of its members served in various official administrative and political positions. The Order based its doctrinal foundation upon Rūmī’s teachings as derived from his writings, and in particular, the Mathnawī. Its members also had a special educational role in the Ottoman pedagogical system. “Since Persian was not taught in Ottoman madrasas (traditional schools),” it was above all “the Mevlevī lodges that provided instruction”[11] and were instrumental in maintaining the enormous prestige of Persian culture in the Ottoman Empire. Due to the unfamiliarity of the general populace with the Persian language, the important task of translating Rūmī’s poetry into Turkish was placed on the shoulders of the Mevlevī translators and commentators (shāriḥān), who, for the most part, benefited from the patronage of the Ottoman court.

Anqarawī’s role in religious disputes with the orthodox ʿulamā’

The arrival of coffee in Istanbul during the mid-sixteenth century and the introduction of tobacco at the beginning of the seventeenth century provided fuel for intense debate amongst ‘ulamā’, who passed competing judgments concerning their legality or illegality. This gave some scholars the opportunity to criticize some of Sufi rituals.[12] In the view of the Qāḍīzādeh, the Sufis were “zindiqs, kāfirs and ahl al-bid‘a” (heretics, unbelievers, and followers of innovation).[13] In order to win public support for their cause, they placed upon the Sufis much of the blame for the social, economic and moral problems that were then confronting Ottoman society. Indeed, the Qāḍīzādeh presented this whole situation as stemming from the displeasure of God at innovation and religious negligence, which they blamed squarely on the Sufis. Qāḍīzādeh’s criticism focused on what was seen as the Sufis’ innovative approach to commentating or interpreting Islamic sources. The majority of Sufi scholarship featured exegesis, Hadith criticism and writings on particular topics that were much discussed during this period.

“With the culmination of the struggle between Sufis and ʿulamā over the legitimacy of various Islamic practices such as music, spiritual dance, and heavy reliance of Sufis on Ibn ʿArabī’s writings, Ismāʿīl Anqarawī enters the historical record.[14] Anqarawī, the nisba of Rusūkh[15] al-Dīn Ismāʿīl b. Aḥmad b. Bayramī Mevlevī (d. 1631), also referred to as Rusūkhī or Rusūkhī Dede, was a prominent Sufi shaykh in seventeenth century Istanbul.”

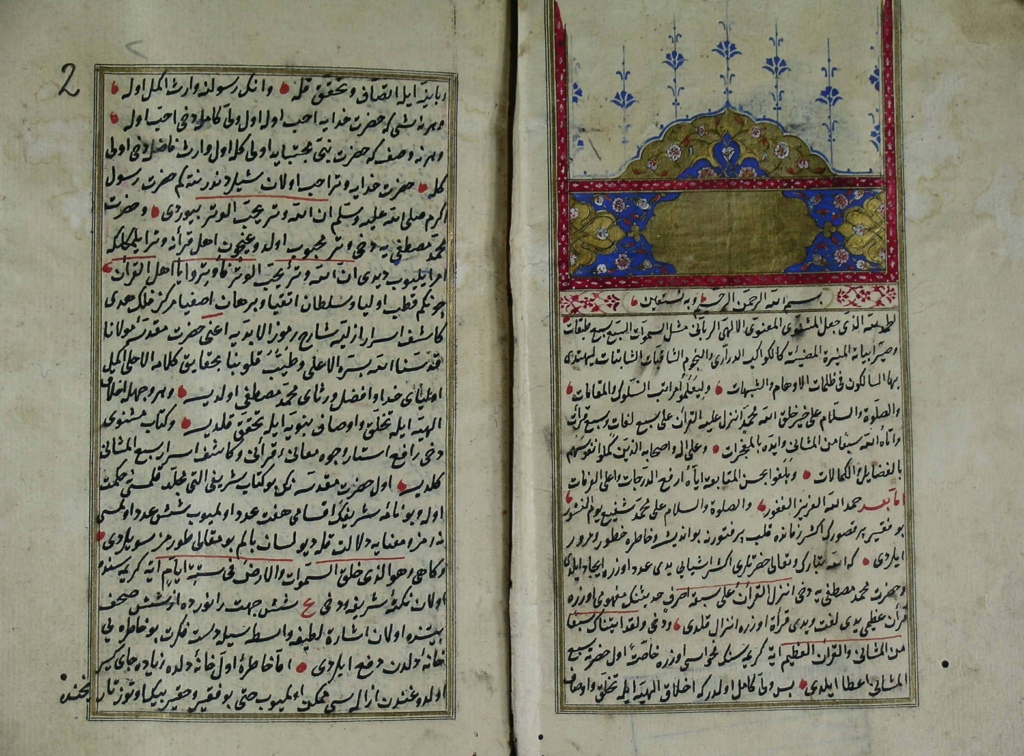

With the culmination of the struggle between Sufis and ʿulamā over the legitimacy of various Islamic practices such as music, spiritual dance, and heavy reliance of Sufis on Ibn ʿArabī’s writings, Ismāʿīl Anqarawī enters the historical record.[14] Anqarawī, the nisba of Rusūkh[15] al-Dīn Ismāʿīl b. Aḥmad b. Bayramī Mevlevī (d. 1631), also referred to as Rusūkhī or Rusūkhī Dede, was a prominent Sufi shaykh in seventeenth century Istanbul. A native of Ankara, his career centered peripatetic study and teaching as the shaykh of Galata Mevlevīhanesi (Mevlevi house) in Istanbul, a position he kept for 22 years until his death.[16] As mentioned in numerous Ottoman biographical sources, including Sākib Dede’s (d.1735) Sefīne-i nefise-i mevleviyān, Hüseyin Vassâf Osmānzāde’s (d.1929) Sefīne-i evlīyā, Būrsālī Mehmet’s (d.1925) Osmānlī müelliflerī and Nevʿīzāde ʿAṭā’ī’s (d.1635) Hadaik-ül-hakayık fi tekmilet-iş şakayık, Anqarawī was the most important Ottoman commentator on the Mathnawī.[17] His writings became a center of controversy and were singled out for their perceived innovation (bidʿa) and their alleged pro-Ibn ʿArabī (d.1240) and anti-traditional stance. A learned man, a formidable religious scholar (ʿālim), and a follower of the Akbarian School,[18] Anqarawī based his commentaries on Ibn ‘Arabī’s doctrines and wrote his own commentary on Ibn ‘Arabī’s Fuṣūṣ al-ḥikam. However, Anqarawī remained a strong advocate of Mevlevī teachings, and was based in one of the most important Sufi lodges of Istanbul, Gālātā Mevlevīhāneh.

Although Anqarawī’s works on fundamental Mevlevī rituals such as “spiritual dance” (samā’) and “meditation” (dhikr) have been thoroughly discussed by scholars,[19] few sources mention the existence of his commentary (sharḥ) on Book Seven of Rūmī’s Mathnawī or the fact that Anqarawī’s commentary on Book Seven was met with significant controversy due to its religiously contentious subject matter.[20] Rūmī’s magnum opus is entitled the Mathnawī-i Maʿnawī, or simply Mathnawī, which is comprised of 25,575 verses and the work is commonly known to be divided into six books. Some sources indicate the existence of a seventh book attributed to Rūmī; however, its true authorship has been the subject of question and most Rūmī scholars cast doubts on the authenticity of the book. According to Kātip Çelebi (d.1657), among early Mathnawī commentators, only Anqarawī attributed this seventh book to Rūmī, basing his position on a text copied in 814/1411.[21] Nevertheless, several copies of this work survive in manuscript form in Turkish libraries, including the Süleymaniye (Istanbul) and Mevlānā Müzesi (Konya), among others.[22] This mysterious “addendum” to the Mathnawī — which, moreover, happened to be heavily influenced by the doctrine of Ibn ʿArabī — could not be easily added to the curriculum of the Mevlevī Order, resulting in serious disagreements among Sufi shaykhs about its authenticity and contents.

“Anqarawī’s commentary on Book Seven made it clear that he was changing the curriculum of the tekke (Gālātā Mevlevīhāneh), as well as claiming authority for himself as the ultimate commentator and Mathnawī-khān (Mathnawī-reciter), a claim which was bolstered by his closeness to Sultan Murad IV (d. 1640).”

Anqarawī’s commentary on Book Seven made it clear that he was changing the curriculum of the tekke (Gālātā Mevlevīhāneh), as well as claiming authority for himself as the ultimate commentator and Mathnawī-khān (Mathnawī-reciter), a claim which was bolstered by his closeness to Sultan Murad IV (d. 1640). However, due to the criticism Anqarawī faced from his opponents, there was an attempt to prevent the manuscript of his commentary on the Mathnawī from being further copied, published or distributed.[23]

Controversy over the commentary on the Mathnawī and accusations of bid‘a

Anqarawī begins his argument with an explanation on the authenticity of the text. He explains that Book Seven appeared in Shām in 1010 (1601/1602 CE) and its appearance came to the attention of Bustan Çelebī, the then leader of the Mevlevī order, who sent a few dervishes to Shām to investigate the authenticity of the book. Upon their return, the dervishes affirmed that the book was authored by Rūmī:

This humble servant (faqīr) heard from reliable sources that Book Seven appeared in Shām sometime around 1010. Its reputation was spread among people, so that even Bustan Çelebī sent a few dervishes to Shām to acquire a copy of the book. The dervishes went to Shām, made some investigations and were able to acquire a copy. Through the divine wisdom (ḥikmat), it became clear who the author of the text is.[24]

By quoting Bustan Çelebī, Anqarawī defends his own position and validates the text by demonstrating that it had come to the attention of earlier Mevelvī shaykhs, who also recognized its authenticity. Anqarawī’s introduction to his commentary, however, provides very little specific information about who his opponents were, and he does not mention their names. However, though he refrains from naming his opponents, Anqarawī does lay out their arguments and expresses his sadness and dismay at their ignorance. He adopts an ad hominem position in answering his critics, questioning their credentials, knowledge and spirituality and lays out their arguments and expresses his dismay at their ignorance.[25]

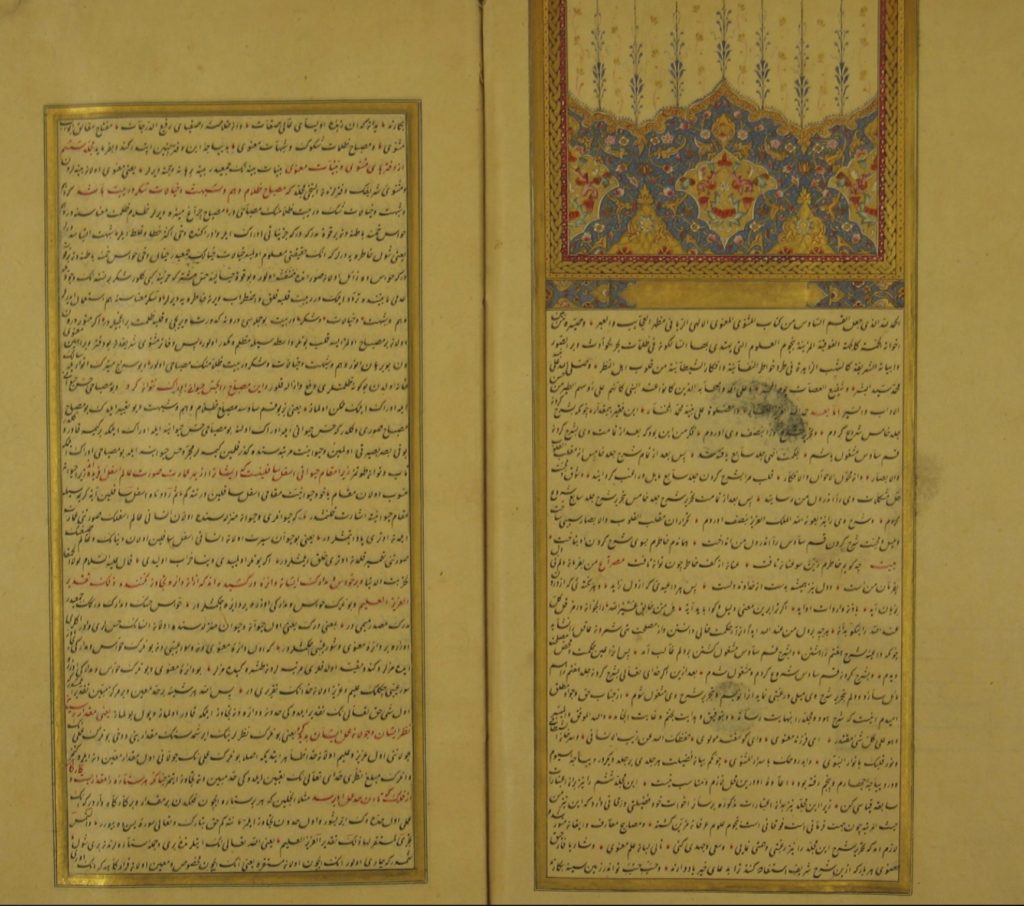

One reason why Anqarawī’s commentary on the spurious seventh volume of the Mathnawī became very controversial was that it addressed subjects strongly opposed by orthodox ʿulamā’. One point in particular that raised the ire of the Qāḍīzādeh was Anqarawī’s tendency to treat the Mathnawī like the Qur’an and to offer exegetical interpretation by comparing its content to the Fātiḥa (the opening chapter of the Qur’an).

Comparing the Mathnawī to the chapter Fātiḥa in the Qur’an

Anqarawī begins his commentary with the an opening prayer of praise for the Mathnawī, which he believed had been written in seven books and which he goes on to compare with the chapter Fātiḥa, also known as sab‘a mathānī (i.e. the Seven Oft-Repeated Verses). He compares the contents of Book Seven to the story of the creation of the seven heavens and to their illumination and solidity, as mentioned in the Qur’an:

And from Him we seek help. All praise is due to Allāh who made the divine Mathnawī in seven strata like seven heavens and rendered its illuminated verses so bright and shining like shimmering planets, and piercing and fixed stars; in order to guide the travelers of the path who suffer from the darkness of illusions and suspicions; and to teach the degrees of spiritual journey and mystical states. Peace and greetings be upon the best of God’s creatures, Muḥammad (PBUH), upon him the Qur’an was revealed in seven words and seven forms of reading and was brought him forward [by God] al-sabʿan min al-mathānī[26] the chapter Fātiḥa “the opener” twice.[27]

These opening words of praise indicate Anqarawī’s high regard for Book Seven and his deep belief that its verses guide spiritual wayfarers through the temptations of mental darkness and illusions. He compares the Mathnawī with the sabʿa mathānī, as though each book in the Mathnawī were a reflection of each verse of the chapter Fātiḥa. Equating a book written by a human hand with the divine revelation inevitably stirred controversy and was considered misleading and as meriting excommunication, if not worse. What made the matter still more complicated was the fact that there was no firm proof that Book Seven was actually written by Rūmī. Thus, Anqarawī could be criticized both for attributing a spurious text to Rūmī and for subsequently declaring all seven books of the Mathnawī to be equal to the seven verses of the opening chapter of the Qur’an, whose importance to Muslim believers may be considered paramount.

The Controversy of Ibn ʿArabī

Another major critique against Anqarawī was his frequent references to and heavy reliance on the controversial School of Ibn ʿArabī. Indeed, Anqarawī defends the views of Ibn ʿArabī at many points in his commentary, both in simple issues and in relation to the major controversies concerning the faith of Pharaoh and the concept of sainthood (walāya). These were the two main subjects strongly opposed by the Qāḍīzādeh ʿulamā’, as discussed by Kātip Çelebī in his The Balance of Truth.[28]

“It has been argued by the well-known Ottoman historian Cevdet Pașa (d.1895) that due to Anqarawī’s conflict with ʿulamā of the Qāḍīẓādeh family, he was forced to disassociate himself from Ibn ʿArabī and make an effort at reconciliation with them.”

It has been argued by the well-known Ottoman historian Cevdet Pașa (d.1895) that due to Anqarawī’s conflict with ʿulamā of the Qāḍīẓādeh family, he was forced to disassociate himself from Ibn ʿArabī and make an effort at reconciliation with them. Cevdet Pașa argues that due to the hostility shown to the School of Ibn ʿArabī by the Qāḍīzādeh family, Book Seven of the Mathnawī gained more attention because Ibn ʿArabī’s name was mentioned negatively in several verses therein.[29] Despite Cevdet Pașa’s argument, Anqarawī implicitly rejects this criticism through his commentary on the verses where Ibn ʿArabī’s name was mentioned, where he declares his support for Ibn ʿArabī. Anqarawī’s reflection on some of the controversial subjects discussed and commented on by Ibn ʿArabī, which had caused controversy and were refuted or harshly criticized by the ʿulamā, included the disputed issue of Pharaoh’s faith and his repentance at the time of death, which merits further discussion. Significantly, in a letter to Abedin Paşa (d. 1906) on the subject of Anqarawī’s commentary on Book Seven,[30] Cevdet Pașa claims that Anqarawī ultimately disassociated himself from the School of Ibn ʿArabī to make peace with the Qāḍīzādeh ʿulamā’.

Conflicts with fellow Sufis

According to Kātip Çelebi, Anqarawī’s commentary was also not received kindly by other Mevlevī shaykhs and members of the ṭarīqat or “Sufi order.”

In an attempt to prevent its usage in Sufi centers, the opponents wrote a letter to Anqarawī presenting four different arguments explaining why the work is not original, and not written by Rūmī, thus it should not be taught in Mevlevī Sufi centers; to which in a long letter, Anqarawī responded to his critics and refuted their arguments.[31]

It was due to Anqarawī’s position and authority within Mevlevī circles and his reputation as a teacher at the Gālātā Mevlevīhāne that, despite the hostility he faced from his opponents among Mevlevī shaykhs, he was able to complete his commentary and use it as an instructional text within the curriculum of his tekke. His efforts also benefited greatly from Sultan Murad IV’s patronage, a fact mentioned in the colophon of the manuscripts. The number of manuscripts of his commentary copied by various dervishes and distributed in various madrasas and Sufi centers likewise indicates the popularity of his sharḥ. The manuscript of his commentary continued to be copied until the Tanzīmāt period,[32] which indicates its popularity with some Mevlevīs at least, especially those residing in Gālātā Mevlevīhāneh.

Conflict with Muṣṭafā Shemʿī / Şemʿî Efendi [33]

“In Anqarawī’s challenge to his critics’ arguments, though he refrained from naming his Mevlevī counterparts, we encounter, for the first time, the name of Mevlānā Muṣṭafā Shemʿī/Şemʿî Efendi (d. circa 1603-1604) as one of his opponents from Khalvatī Sufi Order.”In Anqarawī’s challenge to his critics’ arguments, though he refrained from naming his Mevlevī counterparts, we encounter, for the first time, the name of Mevlānā Muṣṭafā Shemʿī/Şemʿî Efendi (d. circa 1603-1604) as one of his opponents from Khalvatī Sufi Order. Muṣṭafā, who was well known by his pen name (takhalluṣ) Shamʿī/ Şemʿî, was among the famous Ottoman commentators who lived at the time of Anqarawī. He wrote a respected commentary on the Mathnawī at the request of Sultan Murad III; beginning it in 1587 and completing it in 1601. His commentary became popular among the Mevlevīs and was frequently read and taught in Mevlevī lodges.[34] Anqarawī takes Şemʿî to task for his lack of spiritual insight and poor judgment regarding Rūmī’s mystical teachings.[35]

Even if several people of Şemʿî’s intellect and knowledge are gathered in one place, they fall short of comprehending the profound meaning of Book Seven. In fact, they will be perplexed to grasp the in-depth gist of its secrets and concepts.[36]

Anqarawī thus pursues an ad hominem attack against Şemʿî by questioning his credentials. Instead of responding to his critiques, Anqarawī accuses his opponent of lacking spirituality and having a poor knowledge of the Mathnawī. Criticizing his opponents for not being familiar with Rūmī’s work, Anqarawī states, “their dispute looks like a battle with the ego (da‘vā-yi nafs), meaning that, since his opponents do not understand Rūmī’s message, they deny the existence of Book Seven. Whereas, friends of Rūmī are able to recognize his words even in the darkness of doubts and imaginations.”[37] This could reflect the existence of a power struggle among Sufis who did not share similar opinions on the subject of the curriculum of the tekkes and the texts attributed to Rūmī.

Conclusion

There is no doubt that Anqarawī’s full command of Persian and Arabic and his articulate knowledge in the fields of exegeses, theology, philosophy and jurisprudence contributed to his high status in Ottoman society and placed him among the elite scholars who benefited from the Sultan Murad IV’s patronage. This, in turn, contributed to his power and superiority over other Mevlevī shaykhs. It can also be suggested that, by writing a separate commentary on Book Seven, while ignoring other Mevlevī Shaykhs’ disapproval and criticizing other scholars for not being able to understand Rūmī’s Sufism properly, Anqarawī was claiming authority as the ultimate commentator and “Mathnawī-teacher” (Mathnawī-khān). The fact that his sharḥ has been the most consulted among Ottoman commentaries – and remains to this date the only source used for teaching the Mathnawī to Mevlevīs in “Mathnawī-teaching centers” (Mathnawī–khānas) – is a sign of his powerful status and ultimate success.[38] The popularity of his commentary expanded beyond the geographical borders of Turkey and the Ottoman Empire and was considered by Reynold Nicholson (d. 1945) to be the most valuable source of its kind, as he expressed while writing his own English translation and commentary of the Mathnawī.[39]

“The controversy around Anqarawī’s commentary was twofold: first, the sharḥ encountered heavy criticism within Mevlevī circles for its reliance on an apocryphal text, which was of doubtful authenticity, and second, the subjects discussed in the sharḥ caused strong opposition from the orthodox ʿulamā’ on the grounds that it promoted bidʿa.”

The controversy around Anqarawī’s commentary was twofold: first, the sharḥ encountered heavy criticism within Mevlevī circles for its reliance on an apocryphal text, which was of doubtful authenticity, and second, the subjects discussed in the sharḥ caused strong opposition from the orthodox ʿulamā’ on the grounds that it promoted bidʿa. However, by completing and standing by this commentary, Anqarawī asserted his authority as the ultimate commentator and Mathnawī-khān among the Mevlevī Sufis, which was bolstered by his closeness to Sultan Murad IV. The debate surrounding his work helps us to understand the intellectual milieu and social and religious conflicts among the ʿulamā’ and Sufis in seventeenth century Ottoman society.

Eliza Tasbihi completed her Ph.D. in Religious Studies from Concordia University and an M.A. in Islamic Studies from McGill University. She is a Specialised Cataloguing Editor of Islamic Manuscripts at McGill University’s Rare Books and Special Collections and a part-time lecturer. Her core areas of research include Sufism and Sufi literature, classical Persian literature, Ottoman studies and Ottoman Sufi literature, and classical Islam. She has taught and lectured on Sufism, Islamic theology and religious thought, Rūmī and his writings, Western religions, and Persian language at McGill University and Concordia University. She has published articles in Mawlana Rumi Review, the Encyclopedia of Pivotal Events in Religious History, and al-Masaq: Islam and the Medieval Mediterranean.

[1] Kātip Çelebī, The Balance of Truth, Translated by G. L. Lewis. (London: G. Allen & Unwin, 1957), 23-26.

[2] Ibid.

[3] Anqarawī lived during the midst of a struggle between various Sufi groups and the infamous movement of the Qāḍīzādeh family, an influential group who were agitating against religious practices they deemed to be deviations (bid‘a) from proper Islamic belief and practice. For a full account of the Qāḍīzādeh movement, see Marc David Baer, Honored by the Glory of Islam: Conversion and Conquest in Ottoman Empire (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2008); Derin Terzioğlu, “Sufis and Dissidents in the Ottoman Empire: Nīyāzī-i Miṣrī (1618-1694)” (PhD dissertation, Harvard University, 1999); Madeline Zilfi, The Politics of Piety: The Ottoman ʿUlamā’ in the Postclassical Age (1600-1800) (Minneapolis: Bibliotheca Islamica, 1988), Semiramis Cavusoglu’s “The Ḳāḍīzādelı Movement: An Attempt of Şeriat-Minded Reform in the Ottoman Empire” (Ph.D. dissertation, Princeton University, 1990); Necati Ozturk’s “Islamic Orthodoxy among the Ottomans in the Seventeenth Century” (PhD dissertation, University of Edinburgh, 1981); and Simeon Evstatiev’s “The Qāḍīzādeli Movement and the Revival of takfīr in the Ottoman Age,” in Accusation of Unbelief in Islam: A Diachronic Perspective on Takfir, (Leiden: Brill, 2015).

[4] Zelfi, The politics of piety, p. 132.

[5] Özturk, Islamic Orthodoxy among the Ottomans, p. 129.

[6] Khalwatī/Halvetī Sufi order is one of the Ottoman Sufi orders, which was founded by ʿUmar al-Khalwatī, follower of the well-known Sufi Ḥasan al-Baṣrī (d. 728). Khalwa means withdrawal or going to spiritual seclusion and isolation for the purpose of spiritual purification and meditation. For further details on the order see, Frederick De Jong, Sufi Orders in Ottoman and Post- Ottoman Egypt and the Middle East (Istanbul: Isis Press, 2000).

[7] Gölpınarlı, Mevlānā’dān Sonrā Mevlevīlīk (Istanbul: Inkılāp Kitabevi, 1953), p. 185; Özturk, Islamic Orthodoxy among the Ottomans, p. 110.

[8] J. Spencer Trimingham, The Sufi Orders in Islam (London: Oxford University Press, 1973), p. 238.

[9] Ibid., pp. 81-2.

[10] Franklin Lewis, Rūmī: Past and Present, East and West: The Life, Teaching and Poetry of Jalāl al-Dīn Rūmī (Boston: Oneworld, 2000), p. 425.

[11] Ibid., p. 426.

[12] Özturk, Islamic Orthodoxy among the Ottomans 129.

[13] Ibid. 422.

[14] For a complete list of Anqarawī’s writings, see Erhan Yetik, Ismail-i Ankaravi. Hayati, Eserleri ve Tasavvufi Görüşleri (Istanbul: Isāret, 1992); Bilal Kuṣpīnār, Ismā‘īl Anqaravī on the Illuminative Philosophy, His Izähu’I Hikem: Its Edition and Analysis in Comparison with Dawwänts Shawäkil al-hür, Together with the Translation of Suhrawardī’s Hayäkil al-nür. Kuala Lampur: International Institute of Islamic Thought and Civilization (ISTAC), 1996, 1-55; and Eliza Tasbihi, “Ismaʿil Anqarawi’s Commentary on Book Seven of the Mathnawi: A Seventeenth-Century Ottoman Sufi Controversy” (Ph.D. Thesis, Concordia University, 2015), pp. 11-32.

[15] The word rusüh/rasūkh, refers to people who have good knowledge in the field of Islamic sciences, probably from a Sufi perspective; see Būrsālī, Osmānlī müelliflerī i, p. 120; Kuşpınar, İsmāil Anqaravī on the illuminative philosophy, p. 16; and Dayioglu, Galata mevlevihanesi pp. 147-51.

[16] For Ismaʿil Anqarawi’s biography and his commentary of Rūmī’s Mathnawī, see Eliza Tasbihi, “The Mevlevi Sufi Shaykh Isma‘il Anqarawi and his Commentary on Rumi’s Mathnawi.” Mawlana Rumi Review, volume 6, (2015): pp. 163-82.

[17] Tasbihi, “Ismaʿil Anqarawi’s Commentary on Book Seven of the Mathnawi,” pp. 23-5.

[18] Akbarian School is a branch of Sufi metaphysics, which is influenced by the teachings of Ibn Arabī. The word is derived from Ibn Arabī’s nickname, “Shaykh al-Akbar,” meaning “the greatest shaykh.”

[19] Ibid., “The Mevlevi Sufi Shaykh,” pp.183-97.

[20] Gölpınarlı, Mevlānā dān Sonrā Mevlevīlik, 1953; Kātip Ҫelebī, Kashf al-Ẓunūn, 2 vols.

(Istanbul: Wakālat al-Maʻārif, 1941-43), pp.1941-43; Ceyhan’s Īsmail Rüsūhī Ankarav: Mesnevī’nīn Sirri, Dībāce ve Ilk 18 Beytin Şerhi. (Istanbul: Hayykitap, 2008); Kuşpınar’s “Ismā‘īl Anqaravī and the Significance of His Commentary in the Mevlevī Literature,” al-Shajarah, Journal of the Institute of Islamic Thought and Civilization, no.1 (1996): pp.51-57.

[21] Kātip Çelebi, Kashf al-ẓunūn ii, pp.1587-1588.

[22]According to Sa‘īd Nafīsī, Badī‘-i Tabrīzī Muḥtadan va al-Qūnawī, known as Manūchihr al-Tājiriyya al-Munshī, possibly wrote Book Seven of the Mathnawī. Manūchihr was among the students of the Persian poet Kamāl Khujandī (d. 803/1400). Accompanying his father, Manūchihr went to Anatolia in 794/1391 on a business trip and stayed there for a while. For more information, see Sa‘īd Nafīsī, Tārīkh-i naẓm va nathr dar Īrān va dar zabān-i fārsī tā pāyān-i qarn-i dahum-i hijrī (Tehran: Kitābfurūshī-yi Furūghī 1965–1966), vol. 1, p. 194.

[23] Cevdet Paşa, Javāb-Nāmah, In Mekteb. Volume 3. No. 33, p. 309. (Istanbul: Maḥmūd Bey Maṭba‘asī, 1895).

[24] Süleymaniye Library: MS Ayasofya, No.1929, f. 48b.

[25] Ibid., MS Yāzmā Bāgişlar, No. 6574, f. 2a, lines: 15-19.

[26] Among the titles of the first chapter of the Qur’an, al-Fātiḥa, is al-sab‘a al-mathānī. The title is also mentioned in the Qur’an: “and we have certainly given you, [O Muhammad], seven of the often repeated [verses] and the great Qur’an,” [15:87]. See Ibn ‘Abbās, Tafsīr Ibn ‘Abbās: Great Commentaries on the Holy Qur’ān, trans. Mokrane Guezzo, 2 vols. (Louisville: Fons Vitae, 2008), v. 2, p. 327.

[27] Süleymaniye Library: MS Yāzmā Bagişlar 6574, fol. 1b, lines: 1-8.

[28] Kātip Çelebī, The Balance of Truth, p. 133.

[29] Cevdet Pașa, Tezâkir, ed. Cavid Baysun (Ankara: Turk tārīh kurumu basimevei 1986), vol. 4, pp. 229–36.

[30] Ibid., “Letter to Abedin Pașa,” In Mekteb. 1895: v. 3, no. 33, p. 309.

[31] Kātip Çelebi, Kashf al-ẓunūn ii, pp.1587-88.=

[32] The Tanzīmāt period was a time of reform and modernization in the Ottoman Empire that began in 1839 and ended with the First Constitutional Era in 1876.

[33] Shem‘ī is the pen-name of a Turkish translator and commentator of Persian literary works. He became famous in the second half of the 10th/16th century and wrote numerous commentaries on Persian classics, which were dedicated to officials of the Ottoman court during the reigns of Murad III (982-1003/1574-95) and Mehmed III (1003-12/1595-1603). See J.T.P. de Bruijn, “Shem‘ī,” in EI2.

[34] Gölpınarlı, Mevlānā dan Sonrā Mevlevilik, p. 207.

[35] Süleymaniye Library: MS Yāzmā Bāgişlar, No. 6574, f. 6b, lines: pp. 20-3.

[36] Ibid., lines: 34-5.

[37] Ibid., f. 4a, lines: 1-5.

[38] Anqarawī’s commentary on the Mathnawī is commonly known in Turkish as Mesnevī Şerḥi and remains “a primary authority for teaching the Mathnawī and Anqarawī’s name and work have always been expected on the certificates issued to candidates for the position of Mathnawīkhān (i.e. a lecturer on the Mathnawī),” see Kuspīnār, “Ismāʿīl Rusūkhī Ankaravī Ismāʿīl Anqaravī on the Illuminative Philosophy,” pp. 18-9.

[39] In the introduction to volume 2 of his translation of the first and second books of the Mathnawī, Nicholson states, “The oriental commentaries, with all their shortcomings, give much help. Among those used in preparing this translation, I have profited most by the Fātiḥu’l-abyāt (Turkish) of Ismāʿīl Anqiravi and the Sharḥ-i Mathnawi-yi Mawlānā-yi Rūmī (Persian) of Walī Muḥammad Akbarābādī.” Nicholson, Reynold A. Mathnawī of Jalāluddīn Rūmī. Translation, critical edition, and commentary. 8 vols. London: E.J.W. Gibb Memorial Trust, 1925-40., v. 2, p. xvi.