Editor's note: Over the next few weeks Maydan will publish articles presented at the Sectarianism, Identity and Conflict in Islamic Contexts: Historical and Contemporary Perspectives conference held at George Mason University in April 2016. We hope this series will help the broader public to develop a healthier engagement with the concept of sectarianism, an often misunderstood phenomenon.

The creation and strategic utilization, and selective sectarianization of sacred history is a key component of contemporary conflicts between competing social movements and armed groups around the world. This article will highlight the deployment of competing historical narratives in the ongoing conflicts in Syria and Iraq using the concept of “framing.” Framing in this sense refers to the creation of interpretive lenses through which target audiences are encouraged to perceive and experience world events and through which they develop a sense of group and self-identity and solidarity. In order to support their arguments that contemporary conflicts are existentially important to their respective target audiences and membership, rival groups in Syria and Iraq engage not only in physical, military combat but also a clash of socio-political and historical narratives and memories. The conflicts are framed as ones of survival as competing leaders and groups seek to convince their supporters and audiences to undertake severe risks in “defense” of their respective communities. This type of mobilization framing seeks to not only encourage new modes of social mobilization but also to maintain and increase internal solidarity among current group members and supporters.

In the current struggles in Syria and Iraq, self-identified Sunni and Shi‘i groups are engaged in competition and conflict with each other, with both sides claiming to be the “true” representatives of “authentic Islam” and the legacy of the Prophet Muhammad and his companions (sahaba) and family (Ahl al-Bayt). Sunni jihadi groups, such as Jabhat Fath al-Sham (formerly Jabhat al-Nusra) and Islamic State (IS) and Syrian Islamist rebels, such as Jaysh al-Islam and Ahrar al-Sham, for example, claim that they are defending the “People of the Prophetic Tradition and Community” (Ahl al-Sunna wa-l-Jama‘a), that is Sunnis. Shi‘i Islamist parties, militias, and religious scholars adopt similarly absolutist claims. For example, Grand Ayatullah Kazim al-Ha’iri, an Iraqi grand mujtahid living in the Iranian seminary and shrine city of Qom, has, in two fatwas issued in response to questions submitted by groups of his followers in 2013, declared the ongoing conflict in Syria to be one of “confronting unbelief in its entirety,” unbelief that seeks to extinguish the “light of Islam.” These competing narratives draw upon a deep well of historical memory and contested sacred history, providing added gravity to the respective arguments. However, these narratives are also significantly shaped by contemporary political events.The use of historical references are re-tooled and re-deployed to meet strategic needs. The Sunni and Shi‘i groups do not represent “unchanging” or “eternal” narratives and sectarian hatreds, though they do represent a kind of group competition that has existed in differing forms since the medieval period.

“[Contemporary sectarian] narratives are significantly shaped by contemporary political events and their use of historical references are re-tooled and re-deployed to meet strategic needs.”

The expressions of these competing sets of mobilization frames and socio-political and selectively historicized narratives are dialogic, that is they influence and are influenced by the competing narratives of opposing parties, groups, and individuals (or states). In order to achieve frame resonance, that is the creation and successful deployment of narratives and call for activism from specific target audiences, these mobilization frames draw upon the “tool kit” of Islamic cultural symbols, idioms, beliefs, and worldviews in order to successfully portray social mobilization and, in the case of the armed groups, militant activism as not only a socio-political imperative but also a moral duty. These narrative frames, however, only have resonance and the power to mobilize within particular socio-political and economic contexts. The development of sectarian narratives by opposing groups during environments of conflict influences the parallel development and contours of the sectarian worldviews of other communities, which respond by constructing and deploying their own counter-narratives.

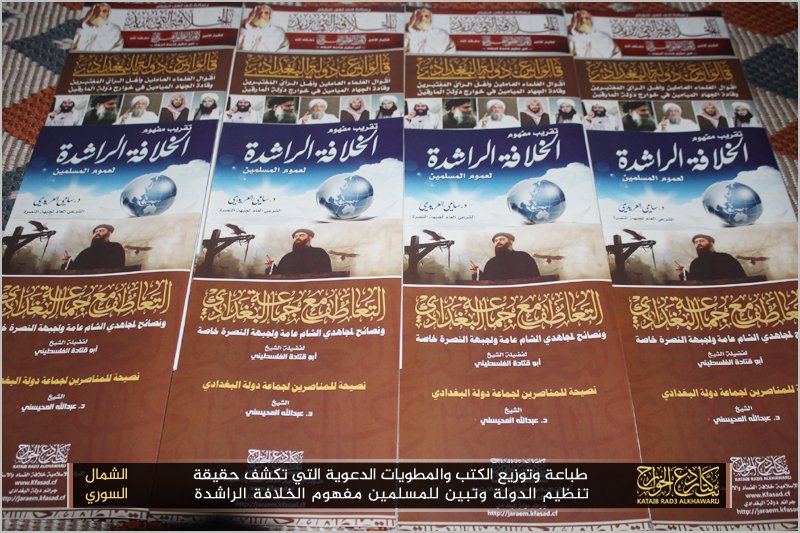

Sectarian Arguments among Contemporary Sunni Armed Groups

Sunni armed groups in Syria and Iraq draw upon both old and new repertoires and re-tooled historicized narratives designed to paint their contemporary Shi’‘i opponents as being heirs to a historical tradition of heretical innovations (bid‘a), polytheism (shirk), and perfidy against Sunnis. Modern conflicts are depicted as only the latest examples of a sordid history of betrayal and corruption by Shi‘a that, according to groups such as IS and Jabhat Fath al-Sham includes the initial “creation” of Shi‘ism by a Jewish convert, Abdullah ibn Saba, in the seventh century, the thirteenth century desertion of the famous Isma‘ili and then Twelver Shi‘i polymath Nasir al-Din al-Tusi and Ibn al-‘Alqami, the wazir to the besieged Abbasid caliph in Bagdad, to the Mongol ruler Hulagu during his conquest of Iran and Iraq. To add weight to their anti-Shi‘i diatribes these groups selectively cite criticisms of Shi‘ism from an array of historical scholars including al-Bukhari (d. 870), Ibn Taymiyya (d. 1328), Ibn Kathis (d. 1373), Muhammad ibn ‘Abd al-Wahhab (d. 1792), and the Najdi Salafi scholar Muhammad ibn ‘Abdullah ibn ‘Abd al-Latif Al al-Shaykh (d. 1921). In some of these accounts Shi‘a are labelled as “fire worshippers” (Majus) in reference to the Zoroastrians of pre-Islamic Iran and “rejecters of true Islam” (Rafida/Rawafid) and Shi‘i militias and Iraqi soldiers are described as “Safavids” after the dynasty that conquered what is now the modern nation-state of Iran and oversaw the gradual conversion of the majority of its people from Sunnism to Shi‘ism between 1501 and 1732.

Islamic State is the most extreme in its anti-Shi‘i rhetoric, though the group builds upon arguments and interpretations shared by some other groups and individuals, including mainstream Salafi religious scholars in countries such as Saudi Arabia. In these narratives Shi‘a are portrayed as posing a greater threat to “Islam and Muslims,” meaning Sunnis, than Christians, Jews, and non-Abrahamic religions. This is because the Shi‘a, unlike the Sunnis, claim to be Muslims when in reality they practice a religion infused with vile theological and creedal perversions and accretions from pre-Islamic faiths such as Zoroastrianism, which include excessive veneration and sanctification of a particular line of the Ahl al-Bayt, worship of these figures at polytheistic shrines, and the seeking of their intercession (shafa‘a) as if they possess divine powers. Islamic State supporters also argue that like the Shi‘a of old, contemporary Shi‘a are allied with “Crusaders” seeking to suppress Islam and Muslims, referring today to the United States, Britain, France, Russia, and other Western European countries together with Zionist Israel and “Hindu” India, the descendants of the Frankish Crusader principalities and kingdoms of the Middle Ages.

Al-Qa‘ida (AQ), in contrast to IS, has long maintained a position of hostile ambivalence toward Shi‘a, though the group’s leaders and chief ideologues, such as Ayman al-Zawahiri and the late Abu Yahya al-Libi, do consider Shi‘ism to be theologically heretical. However, for most of the organization’s history its leadership has not preached open and indiscriminate war against Shi‘a writ large and have instead cited contemporary political reasons for their criticisms and condemnations of Shi‘a and particular leading Shi‘i politicians and religious scholars. For example, al-Zawahiri has long been critical of Grand Ayatullah Ali al-Sistani and other Shi‘i grand mujtahids for not issuing religious opinions (fatawa) and rulings (ahkam) legitimizing armed struggle (al-jihad al-‘askari) in Iraq against the United States, Britain, and the post-Saddam Iraqi government, which the former back politically, financially, and militarily. In a 2013 set of “guidelines for jihad” issued by al-Zawahiri to his group’s fighters and regional affiliate groups in Yemen, North Africa, and Somalia, he imposed strict constraints, at least in theory, on engaging in sectarian fighting with Shi‘a and other “deviant” groups (al-firaq al-munharifa) such as the Ahmadis and Twelver and Isma‘ili Shi‘a. Fighting these groups or segments of them must be limited, according to al-Zawahiri, to defensive actions and fighting should cease once the attackers cease their aggression. The main focus, he argued, should remain on local apostate Muslim regimes and their foreign backers, chiefly the United States. The organization’s position against the Shi‘a has taken a more religiously sectarian tone since the start of the Syrian civil war.

Stronger anti-Shi‘i views are expressed by three of AQ’s regional affiliates, Jabhat Fath al-Sham in Syria, Al-Qa‘ida in the Arabian Peninsula (AQAP), and Al-Shabab in Somalia, though the reasons for this largely have to do with organizational composition and creedal influences such as the strong role of Saudi Salafi jihadis in AQAP, the sectarianized devolution of the Syrian civil war, and the origins of Jabhat Fath al-Sham as originally an offshoot of IS. Another reason is the roles played by veterans of the 1980s’ uprising against the Syrian Ba‘th government of Hafiz al-Asad, and the influence of charismatic Somali Salafi figures in Al-Shabab.

In connecting Shi‘a in the present to historical “villains” such as Ibn Saba, Nasir al-Din al-Tusi, and Ibn al-‘Alqami, groups such as IS and Jabhat Fath al-Sham seek to create a “historicized” propaganda narrative of (alleged) Shi‘i perfidy and hostility toward Islam and (Sunni) Muslims. The contemporary behaviour of Shi‘i political and armed actors is thus put into a “historical” context in which Shi‘a have always sought and will continue to seek to harm Sunnis and Islam while promoting their own deviant religion, which, according to these groups, is nothing more than a gross perversion of “true Islam.” Dialogue and rapprochement are not options because Shi‘a by their very nature will continually seek to undermine, corrupt, and harm Sunnis, no matter what they may claim. Thus, Sunnis are never safe from them and are in need of an always vigilant protector against Shi‘i violence. Groups such as IS and Jabhat Fath al-Sham claim to be such protectors.

On the other hand, Shi‘i militias in Syria and Iraq, along with large segments of Iraqi government forces and the Iranian state, are deploying their own “historicized” propaganda narratives in which contemporary Shi‘i fighters and soldiers are described as the defenders of the Ahl al-Bayt and thus of “true Islam” against the “takfiri” hordes of “Wahhabism,” referring to the latter’s allegations of apostasy against Shi‘a, Sufis, and other Muslims they see as deviant. In other mobilization narratives designed to play off feelings of masculinity, heroism, and vengeance, today’s Shi‘i fighters claim to be safeguarding the “honor” of historical Shi‘i figures, such as Sayyida Zaynab, and acting in “revenge” for the martyrdom of revered religious figures from the sacred past such as Imam Husayn and the other martyrs of Karbala slain by the Umayyads in 680. Modern day Sunni groups, whether they be Syrian rebels or IS and Jabhat Fath al-Sham , represent the “enemies of the Ahl al-Bayt” (nawasib) while the Shi‘i groups are the descendants of the “true Islam” passed down from the Prophet Muhammad through the line of twelve divinely-designated Imams, a mantle now claimed by the Iranian state and other Shi‘i political and religious leaders such as Iranian supreme leader Ali Khamenei.

Figures from the sacred past of Islamic history are not easily divided into “Sunni” or “Shi‘i” classifications in these competing sets of narratives. Indeed, even figures today strongly seen by many to be “Shi‘i” are claimed not only by contemporary Shi‘i but also Sunni actors. These revered figures include even Imam Husayn, the third of Twelve Imams revered in Shi‘ism, who has been claimed also by AQ and IS. In his 2011 eulogy for Usama bin Laden, al-Zawahiri compared the slain AQ founder to Husayn as pinnacles of martyrdom and self-sacrifice for Islam. In audio messages from Abu Bakr al-Baghdadi, the IS leader claims that IS and the Sunnis are the true inheritors of the legacy of “[the second Imam] Hasan and [Imam] Husayn,” not Shi‘a. Rather, the Shi‘a are the descendants of those who assassinated the second Rashidun caliph, ‘Umar, Abu Lu’lu al-Majusi, and the pre-Islamic Iranians (ahfad al-Kisra). Both Iraqi Shi‘i militia and Syrian rebel groups have claimed figures such as ‘Ammar ibn Yasir, a companion of the Prophet Muhammad who later sided with Ali ibn Abi Talib against Mu‘awiya ibn Abi Sufyan, the founder of the Umayyad dynasty. This reverence for members of the Prophet Muhammad’s family and supporters claimed by Shi‘a as their own, such as Salman al-Farisi and Abu Dharr al-Ghifari, has historically also been expressed from within orthodox Sunnism.

The Debate between the Sunni Militant Groups

The deployment of a re-tooled version of sacred history as a weapon in contemporary conflicts is not limited to struggles between Sunni and Shi‘i groups but also takes place between rival Sunni groups. The military and political conflict between IS and multiple other jihadi and Syrian rebel groups, including Jabhat Fath al-Sham and other AQ affiliates, Ahrar al-Sham, and Jaysh al-Islam, has taken increasingly religious and creedal and selectively historicized overtones since the former organization began targeting the latter groups in a bid to expand their fledgling claimed “state.” This has led to a widening, bitter divide between IS and other Sunni militant organizations over who represents “true Islam.” As a result IS declared all of its Sunni Muslim opponents to be “apostates” while anti-IS Sunni groups and individuals, including Sunni jihadis, alleged that Abu Bakr al-Baghdadi’s group are the “new Kharijites,” an extreme puritanical movement that emerged during the tenure of the fourth Rashidun caliph, Ali ibn Abi Talib (656-661).

“References by Jabhat Fath al-Sham and AQ leaders and Syrian rebel groups to the Kharijites are not made in a vacuum and are rather utilized to provide “historical” weight to claims about current events.”

References by Jabhat Fath al-Sham and AQ leaders and Syrian rebel groups to the Kharijites are not made in a vacuum and are rather utilized to provide “historical” weight to claims about current events. They have been utilized to create a narrative component to a worldly political and military struggle between competing groups, a media war that is taking place both on the ground in places such as Syria, Iraq, North Africa, Yemen, and Afghanistan and Pakistan as well in cyberspace in the form of duelling media operations campaigns by the groups involved. Jabhat Fath al-Sham and other anti-IS groups highlight IS’ targeting of other Muslims and particularly other “mujahidin” as well as its ideological and creedal extremism, which includes wanton and haphazard declarations of apostasy (ridda) against all of its enemies, as proof that al-Baghdadi’s organization is essentially “the same” as the original (actual) Kharijites. Similar allegations are made by mainstream, non-armed Muslim community leaders, religious scholars and preachers, politicians, and activists. They refuse to iterate the “Islamic” part of the organization’s name, “Islamic State,” and prefer instead to use “Da’esh/Daesh,” “Tanzim al-Baghdadi” (Baghdadi’s organization), or “Jama‘at al-Dawla” (the ‘State’ Group). Their comparisons of IS and the historical Kharijites (which soon split into multiple different factions) is based almost entirely on strategic analogies that claim to connect contemporary actions by the former with the past crimes of the latter. The assassination by IS of Jabhat Fath al-Sham and Syrian rebel commanders such as Abu Khalid al-Suri in February 2014, for example, is said to be the modern re-enactment of the killing of the companion (sahabi) Muhammad ibn Khabbab and his wife and unborn child in the mid-seventh century. Like the original Kharijites, the argument goes, it is no use trying to negotiate a settlement peacefully with the “new Kharijites” of IS because, as the caliph Ali and his allies discovered, the Kharijites are so ideologically corrupted and barbaric that they only understand the language of violence. IS, in contrast, alleges that its opponents are the “real Kharijites” as well as allies of both the modern “Crusaders” and the Shi‘a.

Conclusion

The adoption of “sectarian” language and rhetoric by contemporary socio-political movements and particularly armed groups in parts of the wider Muslim-majority world, though they espouse a selectively historicized legitimacy, is a thoroughly modern phenomenon, one which cannot be separated from ongoing political, social, economic, and military conflicts and competitions between rival groups over power and (self)- prestige. By claiming historical and religious authenticity in their struggles, these groups seek to tap into their target audiences’ feelings of personal piety, masculinity and the hero complex persecution and oppression, and being under an existential threat. They do this in a bid to increase recruitment and support from the wider community they claim to represent.

“Contemporary opponents are tied to historical villains, portraying modern conflicts as extensions of the past.”

The given conflict is so severe and historically pre-determined, these groups argue, that the only viable solution is violence. Contemporary opponents are tied to historical villains, portraying modern conflicts as extensions of the past. Their competing mobilization frames are dialogic and draw upon selectively “religious” and sectarianized motifs and language. This modern sectarianized discourse is neither wholly “religious” nor solely “political” but is rather a strategic combination of both.