This essay is based on the authors' 2018 journal article: Nada Moumtaz, “Is the Family Waqf a Religious Institution?” Charity, Religion, and Economy in French Mandate Lebanon , Islamic Law and Society 25, 1-2 (2018): 37 – 77.

Can giving to one’s family be an act of charity? In an age of Trumpist nepotism, this might seem like an egregious proposition. But this is the very premise of the family waqf, an Islamic charitable endowment dedicated to the family of the founder, and the most common form of the waqf in the Muslim East from the seventeenth to the nineteenth centuries.

When Muslims found family waqfs, they surrender their possessions to God and dedicate their revenues to family members. In the event of the extinction of this family, these revenues usually revert to the poor. A man surrenders the ownership of his shop to God and dedicates its revenues to some of his children. A mother leaves her house to her unmarried girls. When this shop or this house becomes a waqf, it can no longer be sold, gifted, or mortgaged, because its ownership is with God—save for some exceptional circumstances.

In the nineteenth and twentieth centuries, Muslim scholars, along with colonial officers and lay Muslims from India to Algeria, started to question whether the family waqf was an Islamic institution. After centuries of consensus that it was, Muslim scholars split into two camps: ‘waqf-conservationists’ who considered the family waqf an Islamic institution and called for its preservation and ‘waqf-abolitionists’ who disagreed and called for the abolition of the institution.

These debates arose because of new understandings of religion and economy and changes in dominant perceptions of what counted as charitable. By the 1930s, supporting one’s family by creating a family waqf was no longer considered either a charitable or a religious act that brought its founder closer to God. Family waqfs had become part of the economy, a separate sphere with its own laws, where closeness to God did not make sense.

But this change in how the family waqf was perceived also arose because of a change in understandings of what makes something “Islamic.” How did Islamic legal scholars understand the “Islamic”? How did they construct arguments for and against the waqf as an Islamic practice? Did they use arguments about the economic effects of the family waqf to argue about whether this institution was Islamic? Although it might seem counter-intuitive, legal scholars, I will show, used economic arguments when deriving human interpretations of a divine law.

A debate on the Islamic-ness of the family waqf provides an excellent opportunity to analyze how scholars make their arguments and the kind of evidence they use. Looking at arguments allows us to observe how legal methodology operates and manifests itself. It allows us to see that long-held characterizations regarding the permissibility or impermissibility of certain practices can change.

The Family Waqf Debate in Lebanon and Syria and its Predecessors

The debate over the abolition of family waqfs started in the Levant and Egypt during the first decade of the twentieth century. But the legitimacy of the family waqf had already been put into question by the French in Algeria, in the nineteenth century. For the French, since the waqf could not be sold freely, it stood in the way of settling colonists on land. As the French chair of Islamic studies at the law school in Algiers explained: “We did not conquer such a rich territory to live day to day, without establishing a durable foothold.”[1]

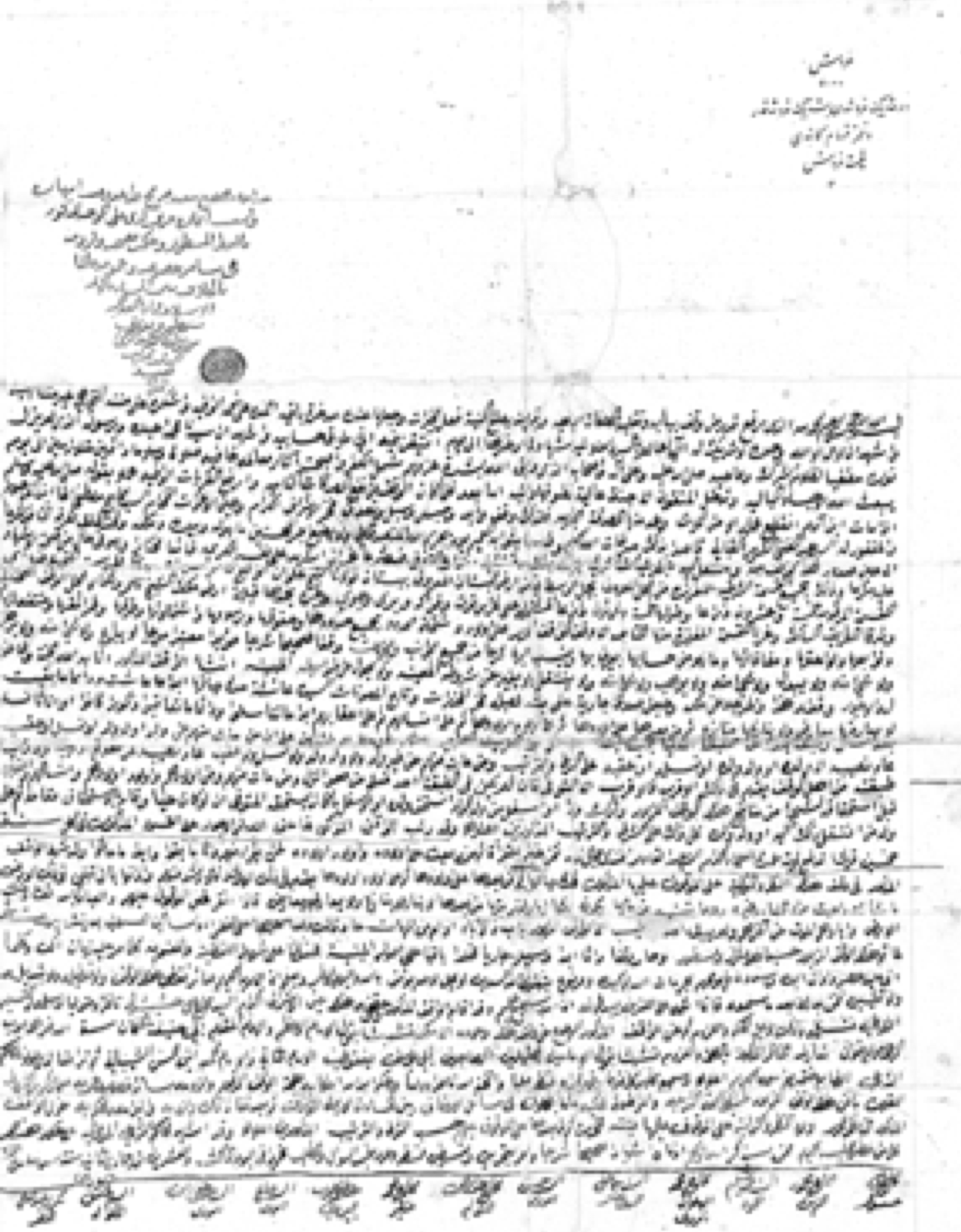

In Egypt, the debate’s most prolonged back-and-forth was between Egyptian Waqf Minister Muhammad Ali Alluba and grand mufti Muhammad Bakhit. In Lebanon and Syria, which came under the French Mandate after the fall of the Ottoman Empire, what triggered the debate was a bill introduced by the Director of the Waqf Directorate proposing to abolish family waqfs. Scholars were split. The main voice of the bill’s opponents, the waqf-conservationists, was the “Scholars’ Association in Damascus” (Jamʿiyyat al-ʿUlamaʾ bi-Dimashq). One of the most vocal supporters of the bill was Shaykh Ramiz al-Malak, a scholar from Tripoli. In epistles, newspaper articles, and fatwas, these scholars fleshed out their arguments and scrutinized those of their opponents, explicitly referencing and borrowing from arguments developed in Egypt.

What explains the position of waqf-abolitionists? Were they collaborating with the French? Could they gain from the abolition of the family waqf? Looking at the biographies of waqf-abolitionists bars any simple answers: some staunchly fought French co

lonial power, while others personally benefited from the family waqf, yet nevertheless stood against it. Nonetheless, we cannot discount class interests, economic interests, and political calculations in explaining the individual positions of these scholars.

“What explains the position of waqf-abolitionists? Were they collaborating with the French? Could they gain from the abolition of the family waqf? Looking at the biographies of waqf-abolitionists bars any simple answers…”

But if we move beyond individual positions, the common thread in the appeal to abolish the family waqf is instead a modern discourse of evolution and “progress.” The calls to reform waqf were always preceded by appeals to enlightenment and improvement. For property like the waqf, improvement manifested in appeals to “freeing” its movement from its perceived archaic shackles.

Let us leave the scholars behind and turn to the terms and arguments of the debate itself: “Is the family waqf a religious institution” (hal al-waqf al-ahli min al-din)?

Step 1: Extracting Family Waqf from Religion

The question of whether the Islamic waqf is a religious institution was possible because of new understandings of religion, or din, as a discrete sphere.

Waqf-abolitionists favored a literalist reading of the Quranic text, which would require the word “waqf” itself to appear in the Quran and to be condoned in order for practice to be considered Islamic. For instance, a waqf-abolitionist in Syria, quoting the Egyptian Waqf Minister Muhammad ʿAlluba, argued that the absence of any Quranic injunctions on waqf meant that waqf was not a religious concept or institution, but a civil one. In such reasoning, the literal Quranic text appears to define what counts as “religious.”

This was far from the most common scholarly position in the Levant. As a waqf-conservationist explained, the Quran provides universal principles (qawaʿid kulliyya), used to derive rules for particular occurrences. To claim otherwise is to show ignorance of the way rules are derived in Islamic law. Such a challenge to the authority of the waqf-abolitionists pushed them to demonstrate their knowledge of legal methodology.

In response, ʿAlluba acknowledged that a major Prophetic tradition justifies waqf as an institution: the Companion ʿUmar founded a waqf based on the Prophet’s recommendation. Nonetheless, he pointed to the variety of scholarly opinions on the validity and perpetuity of waqf. To waqf-abolitionists, t

his disagreement was proof that scholars had struggled to derive the rules of waqf because they could not find any clear mention of them in the Quran or prophetic precedent, save the case of ʿUmar. For waqf-abolitionists, then, all rules that scholars derive without a clear mention in and proof from the Quran and the Hadith and on which there is no scholarly consensus were “civil” and open to revision.

To bolster their argument, waqf-abolitionists contrasted waqf rules with inheritance laws, which are strictly defined in the Quranic text. Quranic inheritance shares acquire a primacy that, as waqf-conservationists argued, denies the complexity of the devolution practices allowed by Islamic law, which includes gifting during one’s lifetime.

Waqf-abolitionists’ arguments for restricting what counts as religious to injunctions explicitly stated in the Quran and Hadith did not go unchallenged. Waqf-conservationists counter-attacked. They contested the attempt to limit the shariʿa to a particular sphere of religion and emphasized a very different understanding of din.

“Waqf-abolitionists’ arguments for restricting what counts as religious to injunctions explicitly stated in the Quran and Hadith did not go unchallenged. Waqf-conservationists counter-attacked. They contested the attempt to limit the shariʿa to a particular sphere of religion and emphasized a very different understanding of din.”

For instance, the Egyptian grand mufti Bakhit argued that, before one could determine whether waqf is part of religion or not, one must define religion. “Based on God’s words in the Quran,” he said, “‘din for God is Islam’ [Q3:19], Islam is the Islamic shariʿa, and the shariʿa is what God has legislated through the speech of the Prophet with regards to belief, worship, pecuniary transactions, punishments, divinely ordained punishments, judgments, and oral testimonies.”[2] In this formulation, waqf-conservationists were arguing that even if waqf were a civil institution and not a religious one, it would still need to follow the shariʿa because the shariʿa encompassed all aspects of a Muslim’s life.

Waqf-conservationists equated shariʿa, din, and religion, all of which comprised the entirety of life, even if they were divided in spheres of worship, transaction, etc. All rules can be derived from the sources of the law —the Quran and the Hadith— even if it is simply a categorization of mubah (indifferent) because this categorization points to a relation to the sources. An act is considered mubah if it is neither prescribed nor proscribed in these sources or by legal reasoning based on these sources.

Waqf-abolitionists equated din with religion, but separated shariʿa from din. Din for them appeared as that part of the shariʿa that was literally sanctioned in the Quran and prophetic precedent, whether it was about worship, inheritance, or criminal sanctions. For abolitionists, other parts of the shariʿa were civil, and their rules could be derived from human reasoning without returning to revelation.

Step 2: Placing Family Waqf in the Economy

The rise of a “sphere” of religion happened simultaneously with the rise of other “spheres” of social life, bound by other rules. Moving family waqfs out of the sphere of religion meant placing them within the sphere of economy, where the waqf would be expected to follow the laws of the economy.

Waqf-abolitionists invoked economic expertise and reasoning to argue that waqf was harmful to the country’s economy, using terms that evoked an image of the nation as possessing an economy governed by economic laws and measurable through statistics.

Waqf-abolitionist arguments portrayed the effects of waqf on the economy as a natural consequence of the economy’s laws (if more land was transformed into waqf, Egypt would lose its credit). Waqf was said to be contrary to the “principles of political economy.” In these accounts, waqf was contrasted with “free property [which] is active, alive, fertile; it changes hands; it can easily find its most suitable owner, the one who will know best how to exploit it,” as a thesis by an Egyptian lawyer on the topic explained. In this understanding of property and the market, the free circulation of assets is the basis of economic progress.

Because they could not be sold, gifted, or mortgaged, save under exceptional circumstances, waqfs were “immobilized” and stood “in the way of freedom of transaction,” according to a waqf-abolitionist. Thus waqfs were also understood to stand in the way of development.

Arguments about harm to the economy were also supported by “official statistics” and data sets. In the 1920s, waqfs constituted one eighth of arable land in Egypt; they were quantified as a totality and analyzed in order to assess the effect of waqf on Egypt’s prime economic resource, land.

These arguments from political economy thus appealed to the authority of economic science, an authority that the successes of Western imperialism have amply demonstrated to the colonized. In the same way that claims of expertise and authority by waqf-conservationists compelled waqf-abolitionists to argue on the grounds of tradition and to use opinions from the various legal schools, the appeal to economic expertise by waqf-abolitionists drew waqf-conservationists toward economic reasoning.

For instance, the Scholars’ Association in Damascus argued that one of the advantages of waqfs was that their revenues allowed for the “creation of commercial enterprises… and exploitation [of the waqf] in the most developed ways that modern civilization and working nations have prescribed.” The former Grand Mufti of Egypt warned that putting all these waqfs on the market would “create a decline in the value [of real-estate] and decrease the value of public wealth, which will create a real-estate crisis and a more general one, which we don’t need.”[3]

We therefore see how even waqf-conservationists yielded to the expertise and authority of economists. They found themselves including arguments about the economic benefits of waqf, rather than only using established legal methods, based on foundational texts, consensus, or analogy.

Step 3: Reforming the Shariʿa Based on the Laws of the Economy

In these first two steps of the waqf-abolitionist argument, the family waqf was presented to belong not to the realm of religion but rather to the realm of economy, where economic experts had shown it to be harmful, constraining economic growth and development. If the family waqf does not belong to religion, why should waqf-abolitionist scholars then be concerned with its value in Islamic Law? Shouldn’t it be left to economists to decide, expunging this discussion from scholarly debate?

The scholars involved in the debate were, however, above all scholars of the Islamic tradition, and they were concerned with reforming the tradition. In the third step, we see them attempting to bring parts of the shariʿa into the realm of the economy by assessing shariʿa rules and legal determinations based on the laws of the economy.

Nonetheless, claims for the necessity of reforming the shariʿa were based on arguments from the Islamic tradition. To accomplish this reform of the shariʿa, waqf-abolitionists proposed that the shariʿa itself required the avoidance of harm.

“…claims for the necessity of reforming the shariʿa were based on arguments from the Islamic tradition. To accomplish this reform of the shariʿa, waqf-abolitionists proposed that the shariʿa itself required the avoidance of harm.”

Indeed, waqf-abolitionists used Islamic legal maxims like “Do not inflict harm or repay one injury with another” and “Bring about benefits and repel harms,” which have been in use for centuries, to argue that that the harm created by the institution of the family waqf should be averted and benefits brought by making it either a reprehensible or a forbidden practice. They used the avoidance of harm in their argument to weigh the multiple opinions that exist in the tradition about the validity of the family waqf.

Again, this reasoning provoked waqf-conservationists, who criticized waqf-abolitionists’ assessments of harm and benefit. They argued that the harm waqf-abolitionists attributed to waqf were inessential and accidental, and had no effect on the value of the family waqf. They gave examples of many practices, like marriage, which might include harm, but whose benefit exceeds their detriment. Such methods of argumentation, attempting to take an opponent’s argument to a ridiculous conclusion (reductio ad absurdum), were common in the Islamic tradition.

Waqf-conservationists also reminded their opponents of the superiority of divine revelation over human reason. In that move, they reasserted traditional legal methodology, particularly the role of benefit in it. For instance, one waqf-conservationist wrote: “Whatever benefits or harms are the basis of the rules of the shariʿa cannot be determined solely by human reason.” By such logic, humans are unable to assess harms and benefits against revelation. Divinely revealed rules should be obeyed even if they bring harm, because they may bring benefits that our limited human understanding cannot comprehend.

This argument thus circles back to whether waqf is justified in revelation, and what counts as revelation, which is where waqf-abolitionists came to question established traditions of reading and interpreting scripture and to foreground more marginal traditions of literalist reading.

Conclusion

In this three-fold argument one can first see the renegotiation of the “Islamic” through the delineation of religion and economy as separate spheres. The “economy” is a sphere whose laws are determined by experts in the economy, and family waqf was placed in this sphere. Therefore, the assessment of the harm and benefit of family waqfs was in the domain of economic experts.

We also see in this argument the way Islamic legal scholars started to incorporate the opinions of economic experts when attempting to determine the permissibility or impermissibility of family waqfs. These scholars advanced modern economic and scientific proofs based on statistical reasoning. The use of economic proofs, I have shown, allowed them to reconsider the assessment of certain acts and practices (like the family waqf) within the Islamic legal tradition. Clearly, even jurists committed to classical legal methodology used economic reasoning. Even more, some scholars attempted to reform the tradition based on the findings of economic experts. Such a use of economic reasoning demonstrates the capaciousness of the Islamic legal tradition and the way it has been able to incorporate modern discourses, such as economics and biomedicine, and their claims to truth.

[1] Shuval, Tal. 1996. “La Pratique de la Muʿâwada (Échange de Biens Ḥabûs contre Propriété Privée) à Alger au XVIIIe siècle.” Revue des mondes musulmans et de la Méditerranée 79 (1): 55–72, 56.

[2] Bakhīt, Muḥammad. 1928. Fī Niẓām al-Waqf, (Cairo: al-Maṭbaʿa al-Salafiyya), 5.

[3] Jamʿiyyat al-ʿUlamā’ bi-Dimashq. 1938. Risāla fī Ibṭāl Risālat al-Ustādh al-Shaykh Rāmiz al-Malak fī Jawāz Ḥall Awqāf al-Dhurriyya, (Damascus: Maṭbaʿat al-Taraqqī), 34.