Introduction

Founded by Abdul Qadir al-Jilani (d. 1166 A.D.[1]) in the 12th century in Baghdad, the Qadiri order has soon spread to and entrenched its status as a major Sufi order in South Asia, during which local sultanates, kingdoms and other Muslim and non-Muslim polities played a significant role. At the same time, multiple Qadiri Sufis and the Qadiri order exerted tremendous influence over these local polities and profoundly affected the socio-political dynamics through their interactions. This paper aims to examine the origin, spread, and development of the Qadiri order in South Asia in relation to major local polities. Particularly, by shedding light upon Qadiri order’s development in the Southern Indian cities of Bidar and Bijapur from the 14th to the 17th centuries, the paper tries to reveal how the Qadiri Sufis interact with local polities, and how these interactions shape the political and religious dynamics in South Asia during this period. Compared to other Sufi orders, especially the Chishti order, the influence of the Qadiri order is relatively limited in South Asia, which in part leads to the scarcity of scholarship in this area. Through close reading and analysis of existing historical, biographical and hagiographical literature, primarily English historical sources of this region, and translated versions of certain tazkiras, and comparisons between Qadiriyya and other Sufi orders, this paper demonstrates how the Qadiriyya interact with political powers in medieval Deccan (the plateau area in the south of the Indian subcontinent), and how mutual interchanges between the Qadiri Sufis and political rulers wielded impacts on the sociopolitical dynamics and trajectories of religious movements in this region.

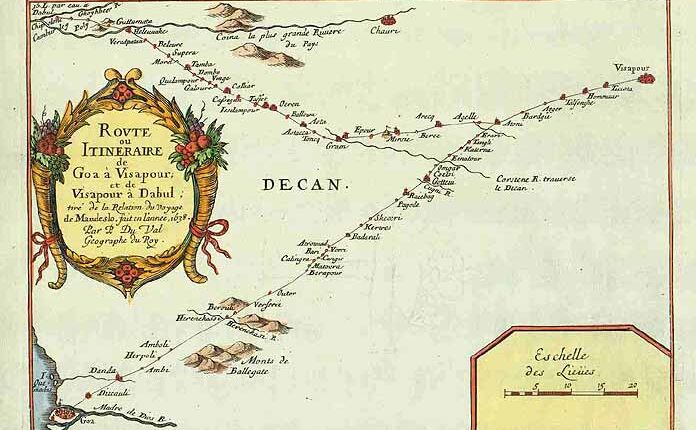

Given the object of study in this paper is the Qadiri Sufis in the Deccan, it would be necessary to give a specific definition to “the Deccan” that is a somewhat obscure geographical terminology.

Given the object of study in this paper is the Qadiri Sufis in the Deccan, it would be necessary to give a specific definition to “the Deccan” that is a somewhat obscure geographical terminology. In terms of the definite demarcation of “the Deccan”, scholarly consensus is yet to be achieved. According to P. M. Joshi, the geographical boundaries of “the Deccan” literally means “the southern and peninsular part of the great landmass of India”,[2] which roughly indicates that “the Deccan” covers all or most parts of the Indian Peninsula while still contains certain ambiguity. Some other academics share a much narrower view of the geographical range of the Deccan. “The Deccan is a term broadly used to describe the lands south of the Narmada River, and specifically meant the areas bounded by the Vindhya ranges to the north, the Western Ghats (Sahyadris) to the west, the Bay of Bengal to the east, and the Mysore Plateau to the south.”[3] The Deccan History Conference held in Hyderabad in 1945 drew relatively more definite limits of this geographical region: “The Deccan shall be deemed to mean the region from the Tapti in the North to the edge of the plateau in the south and from sea to sea.”[4] Joshi also suggests that the Indian Peninsula can be dived into “five distinct physiographical divisions: The western Ghats or the Sahyadri range with the coastal strip, the northern Deccan Plateau, the southern Deccan Plateau, the eastern plateau, and the eastern Ghats with the eastern coast region”. Although “the Deccan” may signify an expansive geographical region, these regions are not of equal significance in terms of religious history: “Historically, these areas (peripheral regions of the Deccan Plateau) enter into medieval Deccan history as territories ruled from a center like Devagiri or Vijayanagar (Bijapur)”.[5] Given the availability of relevant academic sources, and considering the historical presence of the Qadiriyya in this region mainly covers the north or north-central plateau, the paper will focus on this exact region, especially the city of Bidar and Bijapur (Vijayapura) in present-day state of Karnataka, with allusions to and discussions about other locations of relevance in the Deccan.

As to the division of historical periods in the Deccan, there exists multiple different opinions as well. In his study of the history of Sufism in India, S. A. A. Rizvi takes the beginning of the Mughal Empire as a threshold, hence dividing the history of Sufism in India roughly into two major sections: the history before 1600, and the history from 1600 onwards.[6] But Rizvi also clarifies that his studies mainly focused on the Chishtiyya, Suhrawardiyya, Firdausiyya, and Kubrawiyya orders, and he treated the introduction of the Qadiri and Shattari orders in the fifteenth century as early developments before the entrenchment of Sufism in India. Moreover, considering his object of study is the general history of India, the geographical limits of his study cover the whole subcontinent and place more attention on the northern parts instead of focusing on the Deccan. Many other scholars have adopted the term “medieval” from European historiographies in the study of Deccan history. Zareena Parveen, for example, used this term to define the historical period of her study of the Arabic and Persian manuscripts. One could easily sense that the manuscripts and other sources range from the fall of Baghdad in 1258 under the Mongols, to the full-on British colonization of India in the 18th century. Nonetheless, she did not specify the exact commencement and termination of “medieval” history in the Indian, or more specifically, Deccani context.[7] Sherwani and Joshi also borrowed this term in their study of the Deccan history. They also have a clearer definition of when the medieval begun and ended: 1295 as the end of ancient Deccani history and the beginning of the medieval era because it marks the beginning of Muslim military expeditions into the Bijapur Plateau; 1724 as the end of the medieval era and the beginning of modern Deccani history because it witnessed the founding of the Hyderabad State amid the recession of the Mughal Empire and the emerging colonial intrusion.[8] Richard Eaton, in his study of the Indian history prior to British full-on colonization, named the period of 1000 to 1765 as “the Persianate Age”, which in itself reflects his emphasis on the Persian cultural influences on India during this historical time. What’s more interesting is that he further limits the time period of study to 1400-1650 when discussing the Deccan and southern India,[9] which approximately begun with the raid of Timur in northern India in 1398 (which led to massive influx of Muslims to the south), and ended with the fall of the Deccan sultanates and the Vijayanagar (Bijapur) Empire in the 17th century. Drawing upon all these abovementioned literatures, this paper will focus on the historical period of 1300-1700 in the Deccan, between the first Muslim military expeditions in the region and the fall of Muslim rule in late 17th century, as it covers most of the histories when Islam and Sufism, especially the Qadiri order were the most active and dynamic in this area.

Drawing upon all these abovementioned literatures, this paper will focus on the historical period of 1300-1700 in the Deccan, between the first Muslim military expeditions in the region and the fall of Muslim rule in late 17th century, as it covers most of the histories when Islam and Sufism, especially the Qadiri order were the most active and dynamic in this area.

Earliest Sufis in the Deccan

The first Muslim expedition reached the region of Sindh in 711, which later became an incorporated territory of the Umayyad Dynasty and the outpost of the introduction of Islam into the South Asian Subcontinent. The Muslim conquest of Sindh in 711 is recorded in various historical sources. This conquest is usually seen as the inception of the history of Islam in South Asia, which can be evidenced by multiple sources in both Arabic/Persian and Indic languages.[10] In spite of the clarity of the historical records of Islamic reception in the north, as in many other parts of the Muslim world other than the Middle East, the exact time when Islam was first introduced into the Deccan is hard to be determined. In his study of Islam and Sufism in Bijapur, Eaton suggests that oceanic trade with the Middle East was of vital importance in the introduction of Islam into the region. “Islam in western peninsular India first arrived with peaceful enclaves of Arab merchants, who settled along the Konkan and Malabar coasts.”[11] Quoting the records of Arab immigrant settlements in the coastal area in as early as 916/917 from Mas’udi’s travelog, he further argues that “long before any Muslim government was planted on the Bijapur plateau, a tradition of Arab settlement had become firmly established along the western seaports of the peninsula.”[12] Although it’s hard to trace the exact date of the first arrivals of Islam and Muslims in the area, it’s reasonable to speculate that nautical trade was likely the media of introduction and that coastal areas received the first Muslim immigrants from the Middle East at a very early time.

By analyzing the correlations between the transoceanic trade and the history of Kingdom of Bijapur, Eaton reveals that this tradition of trade and exchange over the ocean not only played crucial role in the spread of Islam and the migration of Muslims, but also directly exerted impacts on the economic, sociopolitical, and religious history of the Kingdom of Bijapur. “Horses imported from Arabia through these seaports maintained the Bijapur cavalry, which formed the backbone of the kingdom’s military system. Textiles and peppers exported from the ports sustained the kingdom’s economy to a great degree. Bijapur’s social history was greatly affected by the influx of Iranians, Abyssinians and Arabs coming through these ports from the Middle East.”[13] This shows that the spice and pepper trade across the ocean may be directly and essentially linked to the sustainment of everyday life of the society in the Deccan. What’s more, the trans-Indian-Ocean trade and naval activities were also pivotal to the religious interchanges between the Deccan and the Middle East, which is also supported by Eaton’s studies. “The ports were also important for Bijapur’s religious history in that they facilitated the influx of theologians and Sufis as well as the heavy pilgrim traffic going to and from Mecca.”[14] It is also worth noting that the function of the Indian Ocean in terms of cultural and intellectual interchange and religious mobility has been increasingly recognized by different scholars in their research on this region. As Engseng Ho noticed, “The shifting East-West trade routes, from the Persian Gulf to the Red Sea, brought Hadramawt and Aden into greater contact with Egypt, the Hejaz, and India. This shift, and the new polities it brought forth, had a singular historical result: the creation of a transoceanic ‘new world’ for Islam.”[15] In a way, the Muslim Deccan that thrived during the 14th and the 17th centuries was exactly part of the creation of this “Islamic new world” through transoceanic exchanges.

Another non-negligible factor that needs to be taken into consideration when examining the introduction of Islam and the influx of Muslims into the Deccan is the military expeditions carried out by the Muslim polities in northern India, especially the Delhi Sultanate.

Another non-negligible factor that needs to be taken into consideration when examining the introduction of Islam and the influx of Muslims into the Deccan is the military expeditions carried out by the Muslim polities in northern India, especially the Delhi Sultanate. As noticed by Eaton, the first Muslim military expedition into the Bijapur Plateau in 1296 that was sent out by the Khalaji initiated “an era of repeated raids on the Deccan by armies of the Delhi Sultanate”. In this period, the Deccan was divided into three major kingdoms ruled by the Yadavas of Devagiri, the Kakatiyas of Warangal, and the the Hoysalas of Dwarasamudra.[16] The Khalaji expedition was led by Alau’d-din Khalaji, who was the nephew and son-in-law of the first ruler of the Khalaji Dynasty. The expedition was carried out “with lightning speed” and greatly disturbed Devagiri, the capital city of the Yadavas.[17] Similar military expeditions, raids, battles were soon flocked into the region, making most Hindu states in the eastern Deccan pillaged or defeated by the first decade of the 14th century.[18] The first Muslim polities were set up simultaneously as Muslim military penetrated further into the Deccan. Sultan Qutb al-Din Khalaji first established direct Muslim administrative control over Devagiri in 1318, started “a tradition of lasting Muslim political rule in the Deccan”, which to some extent marks the transition of Bijapur (one major agglomeration in the Deccan) from Hindu to Muslim rule.[19]

The first intrusion of Muslim militaries into the Hindu-dominant Deccan also brought up many side effects that have profound effects on the society and culture of this region. On the one hand, the abrupt military expeditions and the ensuing establishment of Muslim polities brought Islamic cultures that already gilded with Persian and north Indic elements to the Deccani Hindu-dominant culture for the first time, which made the cultural fusions between the two possible and necessary to some extent. Take Bijapur as an example, “the tenuous nature of Muslim rule in Bijapur at this early date and the degrees to which Islam had accommodated itself to indigenous forms” can be evidenced by the architecture of certain mosques.[20] On the other hand, the nascent Muslim polities are relatively fragile and too tenuous to pose any substantial religious and cultural conversions on the local populations in a short period of time. Besides, as the Delhi Sultanate extended its territories further south, the Hindu warrior-states pulled back southwards accordingly. Consequently, a distinct boundary between the Muslim polities and the Hindu ones around the Krishna River in the Deccan Plateau. Bijapur “represented in the early 14th century a turbulent and remote outpost of the Muslim political frontier”. It remained as an outpost of Muslim rule in the Deccan from 1296 to 1347, and then the founding of the Bahmani Kingdom “opened a period of a closer, deeper, and more permanent Islamic rule over the plateau”.[21] “This fifty-year span witnessed the rather turbulent period of transition in Bijapur from Dar al-Harb to Dar al-Islam”, namely from the of war to the abode of Islam, and also witnessed the advent of Bijapur’s earliest Sufis.[22]

Most of the first Sufis that came to Bijapur and the adjacent north-central Deccan Plateau were tagging along with the Muslim expedition army, which means they are most likely military units themselves, instead of professional clerics. Eaton called these early military-affiliated or war-affiliated Sufis “Warrior Sufis”, which is quite a vivid depiction of their complexified missions during that special historical time. The first Sufis entered the Deccan were often viewed ambivalently by historians. Without much doubt, they are usually considered as the first people that brought Islamic culture to the region. However, at the same time, they are also pictured as “militant champions of Islam” that avidly wage jihad against infidels in the expanding Islamic frontier.[23] As both warriors and Sufis, the Warrior Sufis in Bijapur and the broader Deccan at this period shared the combined qualities of both warrior and Sufi, but they were a brief historical phenomenon that was created in a specific context, as Eaton points out, “the Warrior Sufis of Bijapur were not unique in the militant roles they played in the early 14th century”, and they “appeared only briefly in the subcontinent’s Islamic frontier, as the product of unique historical circumstances.”[24]

And in the early decades of the fourteenth century, there are two main waves of Muslim immigration from north India to upper Deccan as well: one is the warriors, soldiers, adventurers and their affiliates that came along with the invading army; the other is immigrants from Delhi that were compelled by Sultan Muhammad bin Tughluq in 1327 in order to strengthen his grasp of this newly acquired frontier.The emergence of Warrior Sufi was coincided with the first invasions of the Deccan from the Delhi Sultanate, as they cannot exist independently from affiliations with Muslim military presence. Similarly, as more lasting and stable Muslim polities, e.g., the Bahmani Kingdom was established in the region, the Warrior Sufis gradually faded out from historical arena because their roles were no longer needed. Furthermore, Eaton believes that the disappearance of the Warrior Sufi may be linked to the assimilative nature of Hindu civilization, which “has usually succeeded in at least modifying if not fully absorbing the many foreign elements that have been introduced into the subcontinent.”[25] Based on this assumption he concludes that the Warrior Sufi may be seen as one of the earliest products that arose from the contact between Arab Islamic and Indic civilizations”, which are diametrically opposed in his opinion. In addition, the establishment of stable Indo-Muslim states, initially the Bahmani Kingdom (1347-1489), and subsequently the Kingdom of Bijapur (1490-1686), “removed the unsettled social and political conditions which had made the Warrior Sufi’s appearance possible”.[26]

In terms of the process of early Muslim settlement in the Deccan, according to Eaton, there are three major patterns: the process of peaceful settlement arising from trade along the west coast; the process of military invasion; and the process of Muslim settlement after the invasion.[27] Eaton argues that both waves of immigrants had lost their ties with the north, which in part led to their declaration of independence from the Delhi Sultanate and the establishment of the Bahmani Kingdom in 1347.[28] This expansive Muslim kingdom lasted until late fifteenth century for about a century and a half, during which diverse ethnicities, cultures and languages coexisted in hybridity instead of mingling together. For instance, the Muslims in the Bahmani Kingdom and the succeeding Kingdom of Bijapur were all divided into two groups: the Deccanis that inhabited the Deccan much longer regardless of their ethnic ancestries; and the foreigners that were usually first or second-generation immigrants from Iran and the Middle East that are deemed to be superior and more privileged compared to the Deccanis.[29]

The relationship between the Qadiriyya and political powers

As one of the first “widespread brotherhoods of mystics acknowledging a common master and using a common discipline and ritual”,[30] the Qadiri order shared certain “pan-Islamic” characters, its followers “spread throughout the Muslim world from India to Morocco”, [31] to quote from Eaton. However, compared to the Chishti order, the Qadiri order reached Bijapur and the Bijapur Plateau relatively late, it did not gain a footing until the end of the fourteenth century. It was introduced to India by Mir Nuru’llah bin Shah Khalilu’llah, who was a grandson of a renowned Syrian Shi’i Sufi scholar resided in Mahan, Iran.[32] What’s more, like many other Sufi orders, the Qadiri doctrine put special emphasis on the reverence of the Saints, especially the founder of the order, Abdul Qadir al-Jilani, also known as “Ghausu’l-A’zam” (i.e., the greatest saint). “To all intents and purposes, the Qadiriyyas advocated the deification of their founders and all his descendants, both of the blood and spiritually.”[33] The Qadiri order also share many similarities with other Sufi orders, e.g., veneration of the descendants of the Prophet (the Saiyids), practice of meditation, focus on lineage and silsila, faith in Islamic scholarships and educational efforts, etc.

Nevertheless, substantial differences do exist in certain aspects of the teachings and practices between the Qadiris and other Sufis. Compared to the Chishti order that’s the predominant Sufi tradition in the Deccan Plateau, the Qadiri order is different in several important aspects: Frist, as mentioned before, the Qadiriyya tends to be a pan-Islamic order, which means it places less focus on the absorbance of Indic autochthonous cultural elements or the “Indo-Islamic cultural fusion” that’s consciously and collectively preferred by many Sufis in India.[34] Instead, the Qadiri order puts more emphasis on its Middle Eastern/Iranian lineage and heritage, and adheres more closely to its Arab character and “led its members in India to emphasize the Middle Eastern more than the Indian aspect of their spiritual (and often familial) ancestry”.[35] Second, Eaton argues that the Qadiri order tends to have more orthodox orientation compared to the Chishti order. “Qadiri Sufis, at least those living in the medieval Deccan, generally upheld this tradition (subordination to the Prophet and conformity to the shari’a) and frequently embraced doctrinal positions hardly distinguishable from those of the regular Islamic clergy.”[36] While he deems the Chishtis to be a little more deviant from the Islamic orthodoxy.

According to the Scottish historian H.A.R. Gibb’s examination of Islam and Sufism in pre-Partition India in his book Mohammedanism: An Historical Survey (1949), the different Sufi orders in India, such as the Qadiriyya and the Chishtiyya can be basically categorized into two groups: “urban” orders and “rustic” orders. Although this study was mainly about the modern development of the Sufi orders in colonial India, Gibb’s observations and conceptualizations of the cleavages between different Sufi orders still help greatly in understanding Sufi orders in history. In Gibb’s mind, the “urban” orders are “founded and maintained by elements of the city populations which were in fairly close association with the ‘ulama and the madrasas”, while the “rustic” orders are “spread chiefly in villages” and are “liable to diverge more widely from the strict tenets of orthodoxy”.[37] Moreover, Gibb not only claims that the Qadiri order was “the most typical urban order”, he even contends that the Qadiriyya was “amongst the most tolerant and progressive orders” on the whole, and was “not far removed from orthodoxy, distinguished by philanthropy, piety, and humility, and averse to fanaticism, whether religious or political”.[38] Based on Gibb’s analysis, Eaton further states that the Chishti order or any other Sufi orders in the Bijapur region can be examined as rustic orders, for their distance from the orthodoxy, specifically the ‘ulama and the madrasas.

Undoubtedly, Gibb’s claim that the Qadiri order is one of the most tolerant, progressive, and politically impartial Sufi orders is fairly reasonable. That being said, we cannot simply take the Qadiri order as indifferent towards politics in the medieval Deccan, because how Sufi teachings and doctrines are applied and carried out is highly contingent upon the local contexts.

Undoubtedly, Gibb’s claim that the Qadiri order is one of the most tolerant, progressive, and politically impartial Sufi orders is fairly reasonable. That being said, we cannot simply take the Qadiri order as indifferent towards politics in the medieval Deccan, because how Sufi teachings and doctrines are applied and carried out is highly contingent upon the local contexts.

As A.J. Arberry argued, there is a common delusion about Sufism that all doctrines of mysticism are essentially one and the same, no matter what religion the mysticism is affiliated with. However, the reality is often that no religious movement that came into being can evolve independently from the influence of other established faiths or beliefs.[39] Therefore, contingent social, cultural, religious and political contexts must be taken into account when looking into how the beliefs and teachings of Sufism are applied in practice. Although the Qadiri order in medieval Deccan has the tendency of leaning into the Arab world for “spiritual nourishment”, as suggested by Eaton, and possesses the quality of political impartiality as claimed by Gibb, the Qadiri Sufis had been engaging with political powers since the very beginning of their presence in the Deccan, and the allure for power has always been a significant factor that shapes the trajectory of development of the Qadiri order in the Deccan.

This kind of allure from the political power to the Qadiri Sufis were especially apparent during the early fifteenth century, when the Bahmani Kingdom witnessed critical socio-political transitions. Established by the Delhi Sultanate nobles and Muslim immigrants from the north in 1347 with its capital in Gulbarga (approximately lies in the midpoint between Bijapur to the southwest, and Bidar to the northeast), the Bahmani Kingdom was the first independent Muslim polity in the Deccan. Due to the lasting patronization of the Indo-Persian culture from the elites, substantial synthesis of the Deccani culture did not occur until Firuz’s reign from 1397 to 1422, during which the sultan actively leaned in favor of the Deccani Hindu traditions, probably as counterforce of the rising power of increasing immigrants from the north and the Middle East.[40] However, after the succession of Sultan Firuz’s brother—Shihab’d-Din Ahmad to the throne, the new political elites decided to move the capital from Gulbarga to Bidar, as a further demonstration of their preference for the Persian-Arab cultures and aversion towards the Deccani autochthonous traditions that had dominated the old capital after decades of assimilations.[41] What’s interesting about this sociopolitical transition of the Bahmani Kingdom is that the Qadiri Sufis almost unanimously conformed with this transition and moved to the new political center Bidar, which evidently demonstrated the intimate closeness between the Qadiri order and the political elites of the Bahmani Kingdom. As Eaton indicates, “the fortunes of the Qadiri Sufis in the Deccan generally followed the fortunes of the Muslim sultanates in whose capitals they lived.”[42]

Moreover, Rizvi’s depiction of Sultan Ahmad’s reception of Shah Ni’matu’llah also provided interesting insights of how the Qadiri Saints were revered by the Bahmani sultans. Shah Ni’matu’llah was well-known for his proficiency in poetry and prose. He travelled from his hometown Aleppo through Iran and Central Asia, and finally settled down in Mahan. He was well-respected among the Qadiri Sufis in India for his intimate relations with the Qadiriyyas of Iran, and for their spiritual genealogy can be directly traced back to him. Sultan Ahmad was so respectful to Shah Ni’matu’llah for his tremendous fame that he sent an envoy to Mahan with luxurious gifts, only to secure a promise of prayer from the Shah for the sultan’s welfare.[43] Here we can see the intimate affinity from certain political leaders towards Qadiri saints in the Deccan at that time period, but that kind of affinity is usually complexified and undergirded by practical political considerations. In examining the abovementioned anecdote, scholars have argued that Sultan Ahmad’s leaning towards Shah Ni’matu’llah was more an intentionally designed political strategy than a mere expression of personal fondness. The time Sultan Ahmad approached Shah Ni’matu’llah and asked for his spiritual blessings, was soon after his transferring of the capital from Gulbarga to Bidar, which forced the sultan to seek for external spiritual support in order to entrench his reign over the new capital.[44] Moreover, the relationship between the Qadiri saints and the sultans was always contingent upon the evolving political circumstances of the Bahmani court. The saints favored by a sultan could easily be discarded by his successors in same cases. Unlike the acclamation received by Shah Ni’matu’llah and his grandson Mir Nuru’llah (who was sent close to Bidar and married Sultan Ahmad’s daughter), Shah Ni’matu’llah’s other grandson, Shah Habibu’llah, was executed at the end of the reign of Sultan ‘Ala’u’d-Din Humayun (1458-1461), for his opposition to the monarch and support for political dissents.[45]

The first Qadiri Sufis travelled from the Arabia to the Deccan arrived in the city of Bidar, the capital of the Bahmani Kingdom around mid-fifteenth century. Eaton argues that the timing of this intellectual influx is crucial for understanding the reason behind these migrations, for the Bahmani Kingdom had entered “an era of a century and a half of domination by the Foreigner class”, who were eager to assert their foreign (Persian / Arab) qualities and shake off the indigenous Indic / Deccani traditions.[46] As discussed above, the conformity of the Qadiri Sufis to the sociopolitical transitions of the Bahmani Kingdom could definitely be explained by the attraction of political power. As a relatively minoritized Sufi order, the Qadiri Sufis faced tremendous extrusions and challenges from other religious and political groups. As revealed by Tanvir Anjum, “Sufism had a problematic relationship with the Muslim establishment—with the custodians of both political and religious authorities.”[47] On the one hand, the political elites were generally suspicious of the Sufis because of their potential of upheaval and usually non-orthodox ideologies. On the other hand, the ‘ulama, especially those under the auspice of the political authority, were usually antagonist even hostile towards Sufis, as they were seen as deviants and potential competitors. This is especially the case for the Qadiri Sufis in the Deccan, as they were often foreign newcomers from overseas, and members of a relatively small dissident religious group wandering at the margin of the mainstream religious and political dynamics. Hence, it’s reasonable that the Qadiri Sufis would eagerly seek political patronage, auspice, even protection.

Nonetheless, the relationship between the Qadiri Sufis and the political power in medieval Deccan is mutually beneficial, for not only the Qadiris got the political patronage they were looking for, but also the political elites got the justification and legitimacy they craved from the presumably orthodoxies of the Qadiri order. In the year of 1422 when the Bahmani Kingdom moved its capital from Gulbarga to Bidar under Ahmad’s rule, the Bahmani elites were as desperate in seeking for legitimacy and justification for their patronage of the Arab / Persian cultures as the Qadiri Sufis were in seeking political protection. On top of that, Qadiri Sufis’ innate tendency towards the Islamic orthodox, the ‘ulama, and the madrasas as an “urban” order, and their presumably prestigious Persian / Middle Eastern heritage and ancestry, and their claim to the spiritual genealogy from Abdul Qadir al-Jilani, were all “perfectly suited to help give the Bahmani court an air of religious legitimacy and piety.”[48]

Summary

The interactions and exchanges between the Qadiri Sufis and the political powers, may provide useful insights for learning Islam and Muslim lives in this relatively marginalized region. The introduction of Islam and Sufism, including the Qadiri order, into the Deccan, was a gradual process that commenced around late thirteenth century and early fourteenth century, during which the transoceanic trade and nautical activities played a crucial role. Around the same period, the military expeditions in this region carried out by the Muslim polities in northern India, particularly the Delhi Sultanate, were also of vital significance.

The Muslim Deccan that thrived through the fourteenth to the seventeenth centuries, is often overlooked by scholars in the field of Islamic Studies. However, Islam and Muslims, particularly the Qadiri Sufism and the Qadiri Sufis in this region from 1300 to 1700, were deeply involved in the political developments of the area.

The Muslim military intrusions of the region, and the turbulent social and political contexts, generated a special group in the first several decades of the fourteenth century — the Warrior Sufis, who were usually affiliated with Muslim military or warfare during the territory expansion of the nascent Muslim sultanates in this region. As lasting Muslim polities established and socio-political order restored under Muslim rule, the Warrior Sufis gradually faded out of the historical arena. In the meantime, the hybridity of complex ethnicities, cultures, languages and religious movements in this region endured the political transitions, and the drastic cleavage between the Deccanis and the Foreigners posed potential risks for future turmoil and conflicts.

The relationship between the Qadiriyya and political powers are dynamic, complex, and interactive. As a minority Sufi order that generally faces suspects and antagonism from both political and religious authorities, the Qadiri Sufis tends to seek shelter and patronage from political powers. On the other hand, Muslim political elites during sociopolitical upheavals, favor to seek connections with the Qadiri Sufis due to their presumably prestigious heritage and ancestry and orientation toward Islamic orthodox, which facilitates the entrenchment of their political legitimacy and religious justification.

___________________________________________________________________

Zhu Tang (汤 铸) is a PhD student in History at the University of Alberta in Canada. He has previously studied Religion at the University of Florida. His main interest of research is focused on the Sufi brotherhood of Qadiriyya, colonial and postcolonial history of Sufism in West Africa, and intrareligious interactions between the Qadiriyya and the Tijaniyya.

___________________________________________________________________

References:

Anjum, Tanvir. “Sufism in History and Its Relationship with Power” 45, no. 2 (2006): 221–68.

Eaton, Richard. India in the Persianate Age 1000-1765. University of California Press, 2019.

Gibb, H.A.R. Mohammedanism: An Historical Survey. 2nd ed. New York: Oxford University Press, 1953.

Khan, Yusuf Husain. “Proceedings of the Deccan History Conference: First (Hyderabad) Session,” 1945.

[1] All years are in A.D. calendar in the paper, unless specified otherwise. A.D. will be omitted below.

[2] Sherwani and Joshi, History of Medieval Deccan (1295-1724). pp. 3-4.

[3] Sohoni, The Architecture of A Deccan Sultanate: Courtly Practice and Royal Authority in Late Medieval India. p. 1.

[4] Khan, “Proceedings of the Deccan History Conference: First (Hyderabad) Session.” p. 19.

[5] Sherwani and Joshi, History of Medieval Deccan (1295-1724).

[6] Rizvi, A History of Sufism in India. pp. 1-2.

[7] Parveen, History of Medieval Deccan As Reflected in Arabic and Persian Manuscripts.

[8] Sherwani and Joshi, History of Medieval Deccan (1295-1724).

[9] Eaton, India in the Persianate Age 1000-1765. pp. 138-90.

[10] von Grunebaum, Classical Islam: A History (600 A.D. to 1258 A.D.). p. 68.

[11] Eaton, Sufis of Bijapur 1300-1700 Social Roles of Sufis in Medieval India. p. 13.

[12] Ibid. p. 14.

[13] Ibid.

[14] Ibid.

[15] Ho, The Graves of Tarim: Genealogy and Mobility across the Indian Ocean. pp. 99-100.

[16] Sherwani and Joshi, History of Medieval Deccan (1295-1724). pp. 31-4.

[17] Ibid.

[18] Eaton, Sufis of Bijapur 1300-1700 Social Roles of Sufis in Medieval India. p. 14.

[19] Ibid. p. 15.

[20] Ibid. p. 16.

[21] Ibid. p. 18.

[22] Ibid.

[23] Ibid. p. 19.

[24] Ibid. pp. 37-9.

[25] Ibid. p. 39.

[26] Ibid.

[27] Ibid.

[28] Ibid. pp. 40-3.

[29] Ibid.

[30] Arberry, Sufism: An Account of the Mystics of Islam. p. 85.

[32] Rizvi, A History of Sufism in India, 1983. pp. 54-7.

[33] Ibid.

[34] Narang and Matthews, “The Indo-Islamic Cultural Fusion and the Institution of the Qawwali.”

[36] Ibid.

[37] Gibb, Mohammedanism: An Historical Survey. pp. 154-55.

[38] Ibid. pp. 155-56.

[40] Sherwani and Joshi. pp. 158-59.

[41] Ibid. pp. 164-65.

[42] Eaton, Sufis of Bijapur 1300-1700 Social Roles of Sufis in Medieval India. p. 57.

[44] Ibid. pp. 55-7.

[45] Ibid, p. 57.

[46] Eaton, Sufis of Bijapur 1300-1700 Social Roles of Sufis in Medieval India. p. 55.

[47] Anjum, “Sufism in History and Its Relationship with Power.”

Tags:

Deccan, Qadiriyya, Bijapur, Vijayanagar, Bahmani Kingdom, Chishtiyya, 15th Century, South Asia, Islam.