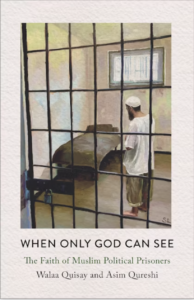

[Book Review] When Only God Can See: The Faith of Muslim Political Prisoners by Walaa Quisay & Asim Qureshi (Pluto Press, 2024 ) | Reviewed by Tarek Younis. ISBN: 9780745348957 ; 256 pp.

For decades, Viktor Frankl’s Man’s Search for Meaning held a special place in psychotherapeutic literature. Frankl wrote his thoughts immediately after having survived a Nazi concentration camp. There he observed a stark difference between those inmates who clung unto some sort of meaning—a purpose to life—and those who did not.

Walaa and Asim’s When Only God Can See echoes Frankl’s Man’s Search for Meaning. Like Frankl’s work, this book is devoted to the multifaceted experiences of those detained in appalling conditions. Focusing on United States and Egypt, the authors ask similar questions of distress and meaning in carceral institutions.

But When Only God Can See is arguably the more essential reading, as it centers on the contemporary and ongoing practices of carceral dehumanisation through the War on Terror. Indeed “counter-terrorism” is an essential subject for anyone interested in liberal processes of dehumanisation.

But When Only God Can See is arguably the more essential reading, as it centers on the contemporary and ongoing practices of carceral dehumanisation through the War on Terror. Indeed “counter-terrorism” is an essential subject for anyone interested in liberal processes of dehumanisation.

The prisons of the United States and Egypt are prime examples in this regard. When Only God Can See is an extraordinary exercise visibilising some of the most erased peoples in the world—political prisoners. Beginning with the harrowing experience of being taken into custody then continuing down the disturbing trail of forced disappearance and torture, the authors underline the intense brutality that is omnipresent in every encounter with State violence. Through these experiences, they shed light on the intricate composite of distress, faith and resistance at every moment.

Erasure and Dehumanisation

It is one thing to suffer, and another thing to suffer in State-manufactured erasure. Such is the unavoidable conclusion I have long-since reached in my clinical work with individuals who have experienced State violence. The significance of erasure, when utilised as a weapon by the State, cannot be overstated. Political prisoners are hyper-invisiblised. This is true physically as well as within public consciousness through manufactured consent that erasure is, after all, the only means to ensure national security. The State assembles its institutions and policies to completely excise political prisoners from public scrutiny. Stripped of rights and disappeared, prisoners are subject to the worst violence humanity has to offer—torture and deprivation, cages and isolation. One need only bear witness to the Zionist entity’s reliance on counter-terrorism in its ongoing genocide of the Palestinian people.

The State assembles its institutions and policies to completely excise political prisoners from public scrutiny. Stripped of rights and disappeared, prisoners are subject to the worst violence humanity has to offer—torture and deprivation, cages and isolation.

Much of the conversations around the War on Terror in the Global North have centered on the particular racialisation of Muslims as existential threats to Western society. While appropriate, the inclusion of Egypt in this book is illuminating. It exemplifies the political utility of counter-terrorism in managing and suppressing political dissent across racial and geographic lines.

At the altar of counter-terrorism, the liberal world has revealed its ugliest face. This sort of erasure, involving the wholesale deletion of human rights, are deeply impactful for political prisoners. This question of theodicy in particular has long preoccupied writers of suffering—the question why God allows such suffering to exist at all. But this book does not waste time on the theory of faith and meaning in suffering. It simply showcases the practice of faith in erasure by allowing the prisoners to speak for themselves.

A Decolonial Praxis of Survival and Resistance

How do Muslim prisoners cope with so much violence? And, incredibly, how do many of them persist? When Only God Can See underscores the faith of Muslim political prisoners in a manner that is, ultimately, at odds with Western healing practices. Muslim prisoners are not drawing on Western-led trauma therapy practices to overcome experiences of repression. Nor are they psychoanalysing their state of total alienation. Rather, by relying on items of faith—like the Quran and fellow Muslims—prisoners not only draw inspiration for their survival. Rather, as the authors demonstrate, this very praxis of faith continues to inform and inspire their resistance towards oppression.

This is significant given the impulse in Western healing practices to individualise and depoliticise experiences of “trauma.” When Only God Can See demonstrates how resilience and survival, as informed by faith, is necessarily political. Faith inspires persistence/survival/healing by giving meaning to the experience and, in the same stroke, immediately informs meaning in the hands of oppression. Prisoners learn to recognise what they’re going through is unjust, that something ought to be done and that, ultimately, everything is in Allah’s hands. Even now during a genocide, while much of the discourse in the West centres around Palestinian pain, trauma and distress to make the genocide legible to Western audiences, Palestinians invoke transcendental frameworks of benediction, justice and accountability. In all this, the book reminds the reader: even in total erasure, as much as it may try, the State cannot separate individuals from their souls.

The Need to Bear Witness

This book is not only about chronicling the experiences of Muslim political prisoners. It is an act of bearing testimony in a process of extreme erasure. The US, Egypt, Israel and others want nothing more than to erase their political prisoners, strip them from their rights, and eliminate them completely. This book is both a rehearsal and a reminder of true memorialisation: to witness and validate those the State attempts to erase. Even if the world erases a person, there is meaning in their erasure that we can all learn from.

The US, Egypt, Israel and others want nothing more than to erase their political prisoners, strip them from their rights, and eliminate them completely. This book is both a rehearsal and a reminder of true memorialisation: to witness and validate those the State attempts to erase.

The authors make clear the erasure does not end with prisons. Indeed, as we know following 20 years of the War on Terror, the prison membrane is thin and porous. Prisons are often just acute concentrations of society’s repression, marginalisation and dehumanisation. While the book does not address Palestinian prisoners, the connection to their experiences remains clear. In some cases, like that of Khader Adnan, the international links of carceral logics are exposed. Adnan was killed by Israel following numerous hunger strikes, and near the end of his life, being informed by Israel that Egypt had issued a fatwa: if he takes his life, it would be considered suicide. It would be foolish then to isolate these systems from one another.

The fields of law and counter-terrorism tend to dominate discussions around Muslim political prisoners. With exception of auto-biographies and the keen insights of critical scholars, less is known how Muslim political prisoners live, suffer, thrive and resist. This book sheds much needed light on the internal and metaphysical experiences of Muslim political prisoners. When Only God Can See, in all its violent depictions, ultimately conveys a message of hope. It demonstrates how, regardless of State violence, inside the prison or elsewhere, the human can not only overcome their oppression, but make it meaningful to themselves and others.

Dr. Tarek Younis is the Racial Justice Researcher at Healing Justice London and Senior Lecturer in Psychology at Middlesex University. He researches and writes on Islamophobia, racism in mental health and the politics of psychology. He teaches on the impact of culture, religion, globalisation, and security policies on mental health. As a registered clinical psychologist, he primarily attends to experiences of racism, Islamophobia, and state violence in his private practice. His book is called The Muslim, State and Mind: Psychology in Times of Islamophobia.