Introduction

By nature, every person’s life is organised in such a way that for his own existence and achievement of the highest perfection, he needs many things that he cannot provide for himself alone. He needs a certain community that can provide each individual with things from the common good. That is why it is only through associations of many people helping each other, where each provides another with some share of what is necessary for existence, that a person achieves that level of perfection to which he is destined by nature. The activities of all members of such a community collectively provide each of them with everything that they need to exist and achieve perfection.[1]

The above statement by Al-Farabi (870-950 CE), the preeminent political philosopher of the Islamic Golden Age, is a pertinent reflection of Islamic communal values and practices of good neighborliness practiced across various Muslim societies. Capitalizing on Al-Farabi’s ideas, the main purpose of this brief reflection is to examine the relationship between (a) Muslim communal values of neighborliness, mutual support and responsibility for those living together in a defined, spacial community and b) the built environment and structures of mosques and community gathering spaces, with a focus on how the existence of such a built environment and infrastructure helps to develop, nurture, and promote Muslim communal values.

…the main purpose of this brief reflection is to examine the relationship between (a) Muslim communal values of neighborliness, mutual support and responsibility for those living together in a defined, spacial community and b)the built environment and structures of mosques and community gathering spaces, with a focus on how the existence of such a built environment and infrastructure helps to develop, nurture, and promote Muslim communal values. The above questions will be explored with reference to the author’s ethnographic study in Uzbekistan focusing on mahalla, an indigenous Islamic community-based institution in Central Asia whose origin dates back to Central Asia’s Golden Age – the 11-12th centuries when the region was ruled by Turko-Muslim dynasties.

The above questions will be explored with reference to the author’s ethnographic study in Uzbekistan focusing on mahalla, an indigenous Islamic community-based institution in Central Asia whose origin dates back to Central Asia’s Golden Age – the 11-12th centuries when the region was ruled by Turko-Muslim dynasties. Derived from the Arabic “mahali,” meaning “local” (Noori 2006), the term mahalla is commonly used in contemporary Uzbekistan to describe the (local) residential neighborhood community uniting residents through common traditions, language, customs, moral values, and the reciprocal exchange of money, material goods, and services (Urinboyev 2013). Today, there are 9361 mahallas in Uzbekistan, and, on average, each mahalla may contain between 500 to 10,000 residents (Noori 2006). Most Uzbeks identify themselves through their mahalla. For example, if a native is asked where s/he lives, the answer will be “I live in mahalla X” (Noori 2006). Thus, everyone in Uzbekistan technically belongs to a mahalla (Sievers 2002). In this sense, mahalla is a residential community association that unites people based on a shared place-based identity.

Even though mahalla institutions exist in both urban and rural areas of Uzbekistan, it should be noted that mahallas are not regionally uniform due to geographic, demographic, cultural and historical factors (Sievers 2002). However, as I will show in the next section, there is one common pattern observable throughout Uzbekistan and Central Asia: in each mahalla, it is possible to find religious and social infrastructure, such as a masjid (mosque) and a guzar/choyxona (teahouse), which provide a conducive environment for developing, and promoting Muslim communal values and practices of good neighborliness and mutual support. These processes become particularly visible when we observe everyday life and social interactions at a mahalla’s mosque and guzar; for example, when inquiring into mahalla residents’ conceptions of a just and fair legal order, or observing how mahalla-based economic practices and risk-sharing activities are given moral significance by being placed within an Islamic framework. These processes will be illustrated below through the ethnographic material I collected during my fieldwork at the Karvon mahalla in rural Fergana, Uzbekistan, between 2009 and 2023.

Fieldwork Context: Karvon Mahalla in Rural Fergana

The Karvon mahalla is situated in the Fergana Valley of Uzbekistan and consists of 120 households (i.e. a population of more than 1500 people). At the time of my fieldwork, the Karvon mahalla, like other mahallas in rural Fergana, had two parallel governance structures: (1) the formal mahalla committee administered by a state-salaried chairman (rais) and his/her assistants, and (2) the informal mahalla administered by an oqsoqol (a leader of the mahalla, and a term that literally translates as “whitebeard”) and an imam/mullah. The chairman had a small state-owned office space located within the territory of the mahalla, while the oqsoqol utilised mahalla-owned infrastructure and social spaces, such as the mosque and guzar, as office space.

This parallel power structure emerged when the government of independent Uzbekistan, following the collapse of the Soviet Union in 1991, formalized the mahallas and incorporated them into the new public administration system as sub-units of the local government (hokimiyat). Even though mahallas are described as citizens’ self-government institutions under the Law on Institutions of Self-Government of Citizens (Mahalla Law), in practice, they are responsible for implementing an extensive array of public administration tasks which are typically fulfilled by state institutions in modern states. This situation can be viewed as a continuation of Soviet-era practices in which mahallas were co-opted and incorporated into the Soviet system of administration as sub-units of the district executive committees (Abramson 1998). Therefore, when discussing mahalla institutions in contemporary Uzbekistan, there is a need to distinguish between the “formal” and “informal” power geometries in the mahalla. The formal mahalla functions in accordance with the Mahalla Law (and other legal acts and decrees adopted by the President and Cabinet of Ministers of Uzbekistan) and represents the long arm of the state within local communities, serving as a sub-unit of the local government and, increasingly, as the (state) mechanism of social control. In contrast, the informal mahalla, revolving around its mosque and community gathering spaces and events, operates in accordance with Islamic values and principles and acts on behalf of mahalla residents when they collectively mobilize around welfare and service provision activities such as the organization of life-cycle events, dispute resolution, maintaining law and order, irrigation/water supply, heating or road paving activities, cleaning, etc..

Given that the mahalla chairman and his assistants worked on behalf of the local state administration (hokimiyat), mahalla residents saw these officials as the “eyes and ears” of the government. In contrast, the oqsoqol and imam, two informal leaders of the mahalla, enjoyed the trust and respect of residents since they worked pro bono and represented the interests of residents vis-à-vis the state, even in cases where the residents’ actions were non-legal or violated the state law. As part of their daily work, these two informal leaders also coordinated life-cycle events (weddings, circumcisions, and funerals); collected donations from wealthier residents and distributed them to needy households; mediated disputes among residents; gathered money from each household for mahalla-based irrigation, heating, or road paving projects; and organized hashar (community-based mutual assistance work) for cleaning and maintaining mahalla-owned infrastructure.

Given that the mahalla chairman and his assistants worked on behalf of the local state administration (hokimiyat), mahalla residents saw these officials as the “eyes and ears” of the government. In contrast, the oqsoqol and imam, two informal leaders of the mahalla, enjoyed the trust and respect of residents since they worked pro bono and represented the interests of residents vis-à-vis the state…

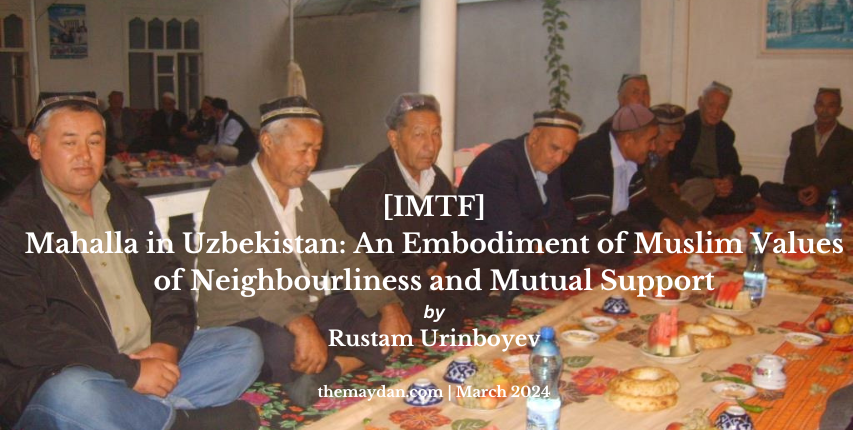

The masjid and guzar were two main public places in the Karvon mahalla where residents came together and interacted on a daily basis. During my daily visits to the masjid and guzar, I usually met around 10 to 15 residents sitting and chatting there, regardless of whether it was the morning, afternoon, or evening. Since the mahalla residents met daily at these social spaces, they served as a key social arena wherein Muslim communal values and practices of good neighborliness and mutual support were developed, reproduced, and enforced. Daily conversations at the mahalla’s mosque and guzar revolved mainly around economic problems, remittances, gas and electricity cuts, and the most recent communal celebrations. Given the existence of job opportunities and fairly good social welfare services during Soviet times, residents expected that the state in post-independence Uzbekistan would continue to have a presence in their daily lives by providing welfare and public goods. As the state in contemporary Uzbekistan no longer provided jobs or comprehensive social welfare services, many households in Karvon increasingly relied on social safety nets and mutual-aid practices within their extended family and mahalla networks. These practices served as a shock-absorbing institution for many residents, enabling them to secure their basic needs and gain access to public goods, services, and social protection unavailable from the state. Having a common residence and meeting and interacting daily at the mahalla’s mosque and guzar created strong moral and affective bonds and thereby produced a general expectation that residents would help their fellow mahalla members whenever assistance was needed. Islamic values played a key role in mobilising such mutual aid practices. Figures 1 and 2 provide a glimpse of these daily encounters at the Karvon mahalla mosque.

The above examples indicate that the mosque at Karvon mahalla was not only a site of communal prayer for residents but also a place where Muslim communal values were developed and reproduced. Despite the Soviet authorities’ zeal to erase and ‘modernize’ the mahalla’s religious and social structures, it is striking that mahallas in rural Fergana were able to preserve their pre-Soviet traditional features. Medieval (pre-Soviet) mahallas were usually a community of several hundred people organised around Islamic law (sharia), rituals, and social events (Geiss 2001). Olga Sukhareva (1976), a Russian anthropologist specializing in the study of mahallas in medieval Bukhara, notes that mahallas possessed their separate mosques, teahouses (choykhona), bazaars, cooking areas, water supplies, cemeteries, and other facilities, which were accessible only to their residents. The most important public space in the mahalla was the mosque, where residents met daily, exchanged news, and made decisions.

While doing fieldwork in the Karvon mahalla, I was struck by how Muslim communal values and sensibilities informed everyday social life and served as a moral and regulatory framework for organizing welfare and service provision activities.

While doing fieldwork in the Karvon mahalla, I was struck by how Muslim communal values and sensibilities informed everyday social life and served as a moral and regulatory framework for organizing welfare and service provision activities. The hashar tradition is one manifestation of such mahalla-based practices, in which residents cooperate and pool their efforts and resources, which may include reciprocal exchange of free/non-compensated labour, money, material goods, and services. The oqsoqol I interviewed said that post-Soviet economic decline has considerably increased the role of hashar as a means to spread the load of high-risk or high-cost endeavours across the community. Mahalla residents might arrange a hashar for various reasons, for example, the organization of weddings, funerals, and circumcision feasts, the construction of irrigation facilities, street-cleaning, asphalting of roads, and many other services and goods not provided by the state. Many residents saw their participation in hashar as an attempt to be a good Muslim and pursue an Islamic way of life.

Accordingly, looking closely at daily mosque conversations and mahalla-based coping strategies allows us to obtain a sense of the texture of how Muslim communal values are embedded in the daily flow of mahalla life. The use of hashar for building the mahalla’s water and irrigation infrastructure is a relevant example in this regard. Since agricultural production is an important source of income in rural Ferghana, one of the main concerns of Karvon residents had to do with water and irrigation facilities. The local government did not provide any funding to build irrigation facilities, for example, installing a pump for getting the groundwater to the surface, which would give people access to water during the agricultural season. On the contrary, instead of securing people’s water needs, the local government used a large proportion of the headwater for the state’s own cotton and wheat production, effectively leaving individual residents without sufficient access to water. For this reason, one of the biggest mahalla-based hashar projects in Karvon was the building of a pump system to enable the use of groundwater for agricultural purposes. As it was an expensive project, Nosir Rahmon (the oqsoqol of the mahalla) and Boymurod (imam of mahalla’s mosque) organized a community meeting at the mosque and collected monetary contributions from each household. The amount of each contribution was determined based on the financial situation of the contributor’s household. Wealthy households made larger monetary contributions than low-income households, while those without sufficient financial means contributed to the pump project with their labor. Nevertheless, despite the mahalla-based efforts, the money collected for building the pump system was insufficient. There were several rich families in the mahalla; however, only one of them, Aziz Hoji[2], decided to finance the remaining part. When I interviewed him, Aziz Hoji explained his decision to finance the pump project as an aspiration to be a good Muslim. As he states, his assistance to the mahalla was driven by his belief that the one who provides water to people would go to jannat (paradise) after death. In doing so, Aziz Hoji gave moral significance to his action by placing it within an Islamic framework, a pattern which can also be observed in many Muslim societies.

…looking closely at daily mosque conversations and mahalla-based coping strategies allows us to obtain a sense of the texture of how Muslim communal values are embedded in the daily flow of mahalla life.

Another relevant example is a road-asphalting project, where residents succeeded in asphalting the roads of the mahalla without any financial assistance or supervision from the local government. Again, a large part of the asphalting expense was covered by wealthy mahalla residents who decided to finance it, believing that their donation to such projects would give them more “savob” (spiritual reward) and thereby make them better Muslims. Hence, Islamic values and principles create a solid moral framework in mahalla life and in everyday social relations in rural Ferghana, where people’s social status and their sense of “being a good Muslim” are determined by their contribution to mahalla projects. While attending mosque gatherings, I noticed that residents regarded the donation activities of the mahalla’s wealthy residents as “acts of piety and charity.” In the words of mahalla residents, sharing one’s wealth with the wider community, giving zakat (the required alms tax in Islam) and ihsan (doing good things for the benefit of others) to poor families were prerequisites for being “a good Muslim.” These observations align with the findings of Johan Rasanayagam, who, in his book, Islam in Post-Soviet Uzbekistan (2011), also demonstrated that the sense of being “a good Muslim” is not solely interior and personal but also produced and expressed in action and relations with others.

The above example shows that Muslim communal values of good neighborliness and mutual support served as a moral compass regulating everyday life and social relations in the Karvon mahalla. This suggests that, in contemporary Uzbekistan, the mahalla and its social and religious infrastructure (mosque and guzar) serve as platforms to realize high-cost, high-risk, yet necessary communal projects in the absence of a protective welfare state. They also enable the local Muslim community reach a level of perfection, using Al-Farabi’s terms, that can only be attained through the association of many people helping each other.

Rustam Urinboyev is an Associate Professor in the Department of Sociology of Law. He is an interdisciplinary socio-legal scholar studying migration, corruption, governance and penal institutions in the context of Russia, Central Asia and Turkey. His research interests and publications cover diverse fields and topics, such as corruption and informality, socio-legal approaches to migration, religious and ethnic identities in Russian prisons, Islamic public administration, law and society in Central Asia, migration and shadow economy, and Russian and Post-Soviet Studies. He is the author of the book Migration and Hybrid Political Regimes: Navigating the Legal Landscape in Russia (2020), published by the University of California Press.

References

Abramson, D.M., 1998. From Soviet to Mahalla: Community and Transition in Post-Soviet Uzbekistan, Thesis (PhD), Indiana University. Ann Arbor: UMI Dissertation Services.

Geiss, P.G., 2001. Mahallah and kinship relations. A study on residential communal commitment structures in Central Asia of the 19th century. Central Asian Survey, 20 (1), 97–106.

Noori, N., 2006. Delegating Coercion: Linking Decentralization to State Formation in Uzbekistan. PhD Dissertation. Ph.D. Dissertation. Columbia University, New York.

Rasanayagam, J., 2011. Islam in Post-Soviet Uzbekistan: The Morality of Experience. Cambridge University Press.

Sievers, E.W., 2002. Uzbekistan’s Mahalla: from Soviet to Absolutist Residential Community Associations. The Journal of International and Comparative Law at Chicago-Kent, 2, 91–158.

Sukhareva, O.A., 1976. Квартальная община позднефеодального города Бухары (в связи с историей кварталов) (Kvartal’naya obshchina pozdnefeodl’nogo goroda Bukhary: V svyazi s istoriei kvartalov). Moscow: Nauka.

Urinboyev, R., 2013. Living Law and Political Stability in Post-Soviet Central Asia. A Case Study of the Ferghana Valley in Uzbekistan. Ph.D. Dissertation, Lund Studies in Sociology of Law. Lund University, Lund.

[1] Abu Nasr Al-Farabi, Filosofskie traktaty (Philosophical treatise), 1972, p. 303, Almaty: Nauka (author’s own translation and interpretation from Russian into English)

[2] Hoji is a holy title which is given to a Muslim who has successfully completed the hajj (pilgrimage) to Mecca.