“Muslim minorities in the non-Muslim world will ultimately realize that their history has put them in a position somehow reminiscent of the Prophet’s Meccan period. Their isolation will purify and strengthen their belief. It will refine their thought and make their tools precise, and at an appropriate time, they will start to send ‘expressive’ postcards home. Then there will begin another migration, not in space and time, but from blindness of a certain kind to a clearer vision, from spiritless materiality toward expressive spirituality.” – Gulzar Haider[1]

Introduction

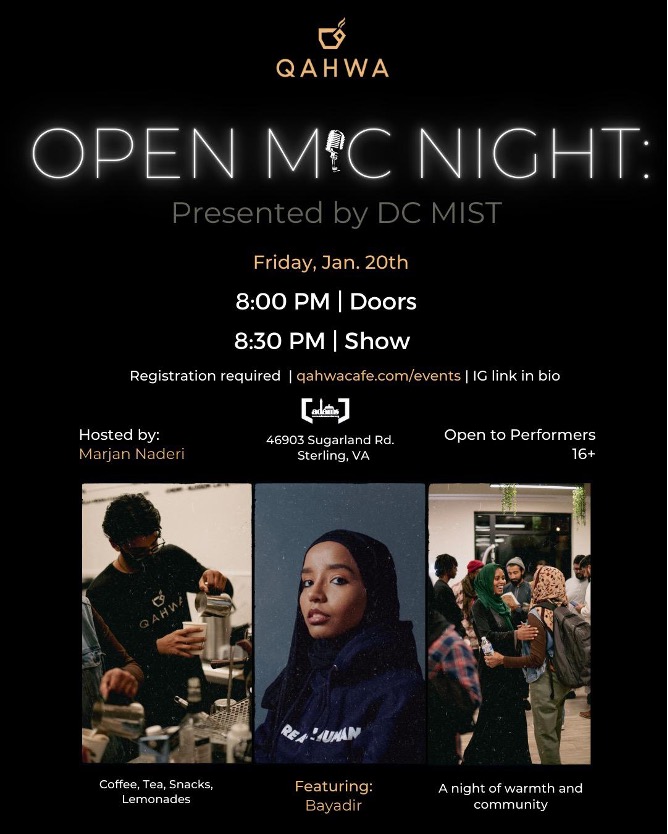

“I didn’t feel like I had a space, I didn’t feel understood, I didn’t feel accepted, I didn’t feel religious enough, I didn’t feel like the masjid was for me…” So says Ali Altalib, one of the founders of the Qahwa Café and Youth Center of the All Dulles Area Muslim Society (ADAMS) in Northern Virginia and the suburbs of Washington DC. Ali’s sentiments are relevant to Maria Dakake’s opening essay “Reflecting Muslim Community Ethics in the Built Environment” where she invites contributors to reflect upon “the connection between Muslim ethics and aesthetics in the communal environment.”

Previous essays have responded to Dakake’s call by focusing on The Ethics of Place and the Production of Space, The Women’s Mosque , and the Spiritual Community of Dar al Islam. This blog will address youth issues, specifically young Muslims attempting to create structures that represent themselves within the context of Muslim American communities. While there is literature on Muslim youth spaces, its focus is generally on “virtual” or “minority” spaces, making the study of the “built environment” of Qahwa all the more important.[2]

“So that they are prepared for what is next”: The Next Initiative and the Idea of a Youth Cafe

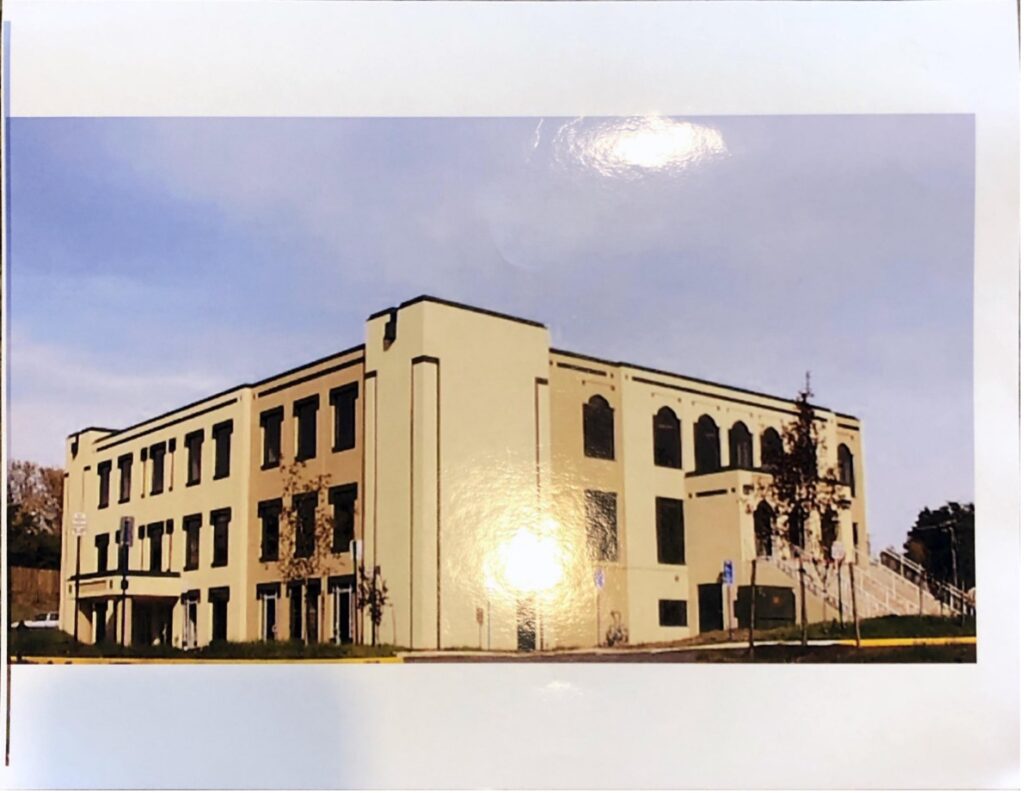

Since the 1980s, the ADAMS Center has consistently prioritized involving the youth of the local Muslim community. For instance, when ADAMS built their permanent space in the early 2000s, they focused on classrooms, a youth room and a gym over a permanent prayer space (musalla), which would only be completed 15 years later. In the 2010s, youth programs continued to flourish such that a group of youth and mentors developed the “The Next Initiative” between 2013-2015. The Initiative called itself “Next” because the youth are “the next men and women to lead this nation. If they are properly nurtured at a young age…will be the next teachers, parents, scholars, doctors, and entrepreneurs who positively contribute to the ADAMS Community.” The Initiative saw investing in youth as essential to the future of ADAMS, as it would help create professionals that in turn would reinvest in the congregation.

In its own words, “The Next Initiative pushes young people to start acting now, to start getting involved now, to start studying hard now, to plan wisely now, so that they are prepared for what is next.”

The Next Initiative Committee envisioned that once ADAMS built its permanent prayer space (musalla) the older parts of the building would be abandoned leaving room for the youth to expand its space. The Next Initiative sought to have a youth center as “part” the mosque and not as a “separate entity” away from their parents and elders. They learned that a donor had given $250,000 for youth programming and that they would create a café that would become a “sound business,” eventually sustaining the various youth programs and activities. While the Next Initiative called for a host of improvements – from gym renovations, to a youth director’s office, to a game room – it was the café that received the most attention.

“The café would serve the youth and community in multiple areas from financial self-sufficiency to socialization and entrepreneurship.“

The café would serve the youth and community in multiple areas from financial self-sufficiency to socialization and entrepreneurship. First, the cafe would help fund youth activities. Historically, the youth fundraised for their own programs through bake sales, car washes, and other initiatives. The café would be an expansion of the traditional bake sale model and thereby fund various youth-related trips, programs and lectures. Second, it would become a place to hang out and for “families to come and eat together and bond through purchasing and enjoying halal food at the center.”[3] The café would be a “halal” space where young congregants could buy food, spend time with their families, and engage with one another. It further aimed to attract a certain demographic outside of ADAMS regular attendees and increase the donor pool and membership count. Finally, the café would provide work and internship opportunities where youth could learn real-life skills that would later help them in their careers and professional lives. Instead of working in fast food chains or department stores, young congregants could work in the masjid and gain expertise related to entrepreneurship and management.

However, the Next Initiative was not able to get off the ground as they were unable to get sufficient support from the Board, which led to disenchantment and disillusionment. One of the main writers of the Next Initiative, Samee Khan, recalls presenting to the Board, who claimed that it was the best presentation that they had ever seen. Yet there was no individual on the Board willing to take ownership of the Project, which led to it being indefinitely delayed.

“Architectural Sunnah”: The Qahwa Café and Youth Center

Initially, backers of the Next Initiative felt disappointed that their efforts seemed to have failed at the very same time as key youth staff left the masjid.4 However, the dynamic began to transform when youth who had grown up in the masjid began to join the ADAMS board themselves. One of these was Ali Altalib who was now a young professional with a family of his own trying to determine how to give back to the community and create a hospitable environment for his children. Growing up, Ali felt “imposter syndrome in almost every environment. I wasn’t ‘Arab’ enough for the Arabs, ‘Muslim’ enough for the Muslims, ‘American’ enough for the Americans, ‘immigrant’ enough for immigrants and so on. The only place that felt like home was during the monthly youth sleepovers at my Masjid, where I could fully be myself amongst my peers” Like many Muslim American youth, Ali felt a crisis of split identities but was able to find himself within the masjid with his peers.[4] However, as he began to grow older, he also felt a sense of disconnect from the masjid as he did not find the programing relevant to his daily struggles. This would dramatically change after 9/11 where he recalls that “My identity was under attack on all fronts, and I found myself having to justify my existence everywhere I went.” He was saddened to see Muslims changing their names and scared to express their identity which eventually propelled him back to the masjid and his Muslim friends. He began to wear a kufi everywhere to let “Islamophobes know what’s up, and that their hatred will never prevail.”[5]

In later years, he worked to get involved in the masjid and participated in hundreds of “WhatsApp conversations” on how things need to change, from the masjid operations to politics. But he hated being “an armchair critic,” so he decided to run for the Board of Trustees and in 2019 formally joined the Board. During one of his first board meetings, some trustees complained that young people were not coming to the masjid anymore, and they wanted to find a way to bring them back.[6] The existing youth programming was geared towards “religious masjid kids, which was a distinct minority of the broader Muslim Youth population.” As the conversation progressed, Ali “instinctively knew that this was his mission” and it became one of his top priorities to create space for a broad section of young Muslims. He recalls, “I was viscerally moved to accept this challenge as it triggered some of my own feelings when I was a youth in the same masjid. I didn’t feel like I had a space, I didn’t feel understood, I didn’t feel accepted, I didn’t feel religious enough, I didn’t feel like the masjid was for me…” Ali began to do research on the youth center and learned about the $250,000 donation designated for youth programming and the Next Initiative Proposal. He surveyed the young congregants again and learned that the youth café was still a top priority. Afterwards, he recruited experts in marketing, branding, cafe operations, interior designing and architecture, in an attempt to make the project’s revival a success.

Aatif Sharieff, who was from the same generation as Ali, became the chief architect. In his design, he sought to define an “American typology for Islamic Architecture.” According to Aatif, a unifying thread of Islamic Architecture was that it historically “absorbed different cultures” – particularly those of its current context. Aatif therefore sought to move away from architectural models that simply replicated mosques from other parts of the Muslim world and instead deeply considered the current context and need. In regards to the Qahwa café, Aatif explains that the design of the space was based on “the principal of ‘Architectural Sunnah,’” which hearkens back to Madinah’s very first mosque: “comprised of a dirt floor, unadorned walls and a thatch roof made of palm fibers.” In a similar way, Aatif sought to provide a “minimal design approach” while offering an experience that was parallel to “major retail developments” and “high-end coffee shops.” He recalls, “I personally felt that the quality of the design and construction would be the distinguishing factor to attract the youth to a ‘cool looking modern space’.” His favorite element of the cafe is the roof terrace, which utilized existing infrastructure to add an extra, refreshing space. He designed the division between the café and the rest of the mosque to be transparent, to make it open and inviting.

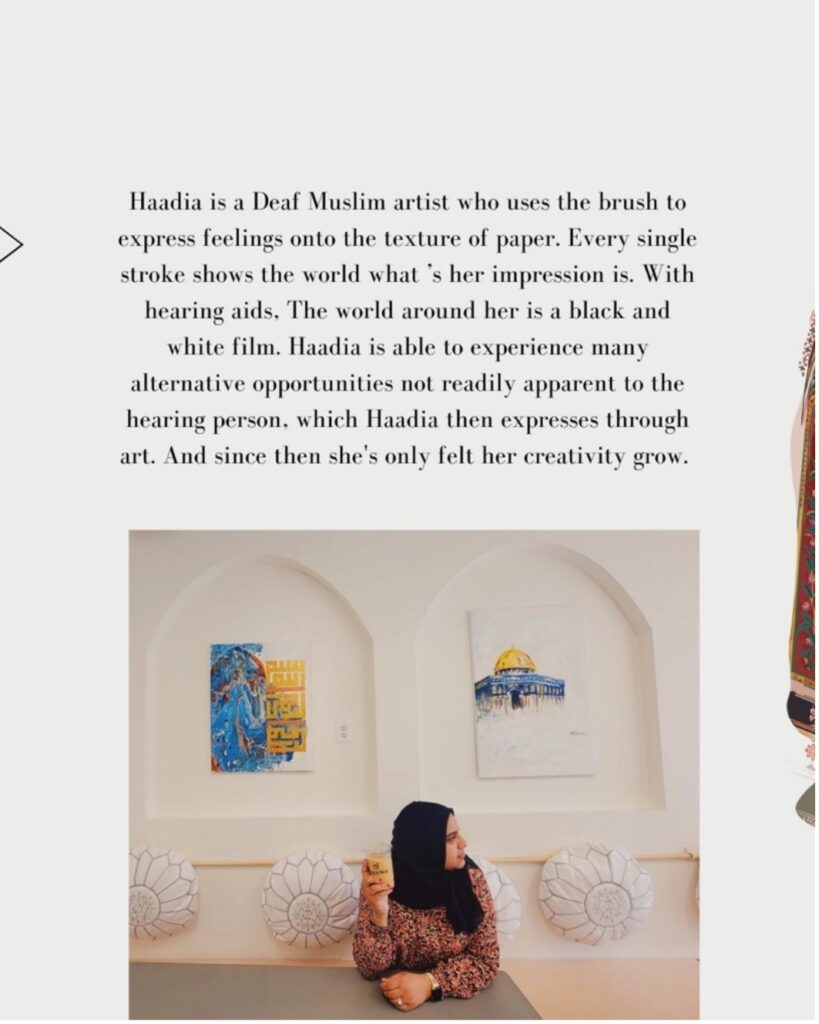

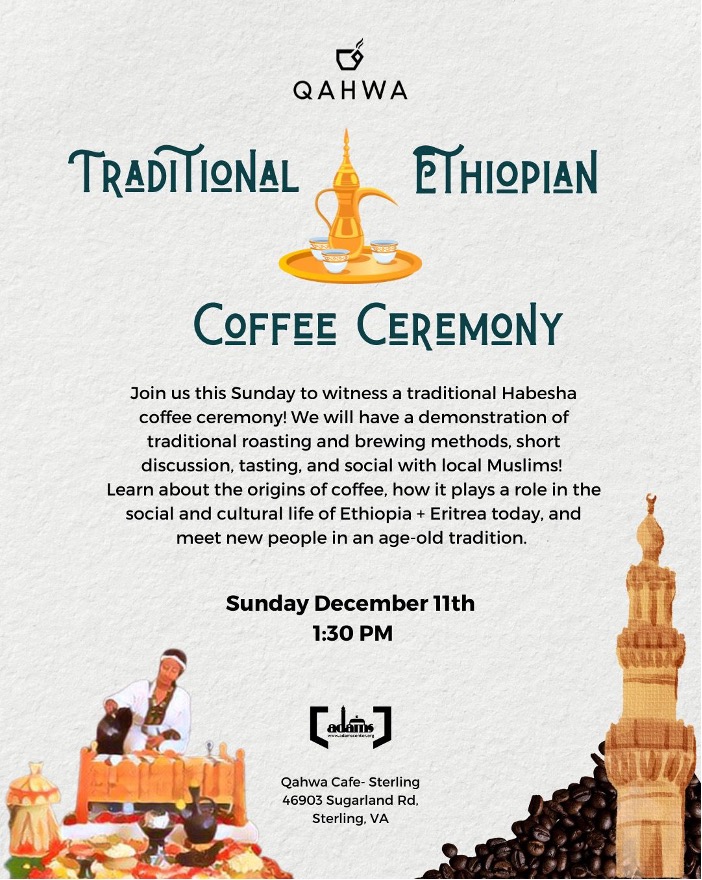

Another expert, Sosan Azmeh, worked on the branding. Sosan took a similar youth-centered approach, stressing that the branding emerged from youth surveys and consultations. The youth choose the name “Qahwa” which means coffee in Arabic, and she designed branding that was “green, warm, inclusive, clean, and modern” and that reflected values of “inclusivity, spirituality, creativity, and growth.” Sosan thinks of “Qahwa as a safe third space within the masjid, which sounds like a paradox. We can offer the youth a space where they feel like they’re in a cool third space, but which has the baraka (blessings) of being in the masjid.”

After Ali and his team created the initial designs, he presented a proposal to the Board, who approved the project and resolved that any net proceeds from the café would be used to exclusively support youth programming. He then began to collaborate with the construction committee, which included Omar Ashraf, who led construction efforts on the first phase (see above), and Arif Rahman, a professional engineer who helped build the permanent prayer space (musalla) expansion. The project began to pick up momentum, but then COVID hit. Everything came to “screeching halt,” but the team eventually restarted virtual meetings and continued to move forward despite the various obstacles and challenges. During the pandemic, the masjid was empty and there was no programming, which created a perfect opportunity for the construction of the café without interruption. Although rising prices during the pandemic threatened to derail the project due to insufficient funding, the team pressed on and organized a youth-led virtual fundraiser which surpassed the fundraising goal. Construction was able to continue and Qahwa opened its doors to a loud celebration on December 10th, 2021 and continues to operate with regular and diverse programming that caters to the youth and young adults.

“During the pandemic, the masjid was empty and there was no programming, which created a perfect opportunity for the construction of the café without interruption. Although rising prices during the pandemic threatened to derail the project due to insufficient funding, the team pressed on and organized a youth-led virtual fundraiser which surpassed the fundraising goal.”

Conclusion

The case of Qahwa is unique because it is a youth center inside a major masjid, encouraging “the cultivation of both communal and individual virtue,” and affirming that children and youth are an essential part of Muslim devotional and communal spaces. In many countries where immigrant congregants originally come from, the masjid is primarily an adult male space where it is unusual to see children and young people. However, from the beginning, ADAMS intentionally designed their masjid to prioritize youth and children. The Qahwa Café and Youth Center was successful because it built on this history and was able to incorporate young congregants who grew up in the masjid to its board and leadership. Thus ADAMS, along with other American masjids, has transformed from simply a “prayer space” to a “community space” where Muslim youth in a minority context find “refuge” and a “safe space” to express, articulate, and form their emerging identities.

*Top Image: Qahwa has become a hub and place of community gathering and socializing. Here community members crowd the space to watch the 2022 Morocco v. Portugal World Cup match.

Younus Y. Mirza is a Visiting Researcher at Georgetown University and Director of the Barzinji Institute for Global Virtual Learning at Shenandoah University which seeks to improve America’s relationship with Muslim-majority countries. He is currently writing a book about the Islamic Mary. To learn more about his scholarship, teaching and speaking, please visit his website http://dryounusmirza.com

[1] Gulzar Haider, “Muslim Space and the Practice of Architecture,” in Making Muslim Space in North America and Europe, ed. Barbara Metcalf (University of California Press, 1996).

[2] Chris Shannahan, “Negotiating faith on the Coventry Road: British-Muslim youth identities in the ‘third space’,” Culture and Religion 12, no. 3 (2011): 237–257; Amelia Johns, “Muslim Young People Online: ‘Acts of Citizenship’ in Socially Networked Spaces,” Social Inclusion 2, no. 2 (2014): 71-82.

[3] This statement is reminiscent of other youth spaces such as the ones in Sarajevo: “What is valued by young believers is not just the opportunity to socialize, but rather an opportunity to socialize with likeminded peers in an environment perceived as morally sound”; Andreja Mesaric, “‘Islamic cafes’ and ‘Sharia dating:’ Muslim Youth, Spaces of Sociability, and Partner Relationships in Bosnia-Herzegovina,” Nationalities Papers 45, no. 4 (2017): 588. Mesaric explains that “the foremost marker of an Islamic cafe is that it does not serve alcohol. These cafes also often play modem interpretations of ilahijas and kasidas, religious Muslim songs exalting God and dedicated to other religious subjects, respectively. Guests and staff in Islamic cafes greet each other with selam alejkum and part saying Allah emanet, a phrase meaning ‘entrusted to God.’ This serves to mark these spaces as belonging to the faith community… What makes a cafe an Islamic space is above all its continuous inhabiting by practicing believers who engage with each other, in a morally correct manner”; Mesaric 599. For more on cafes in Muslims spaces, see Lara Deeb, Leisurely Islam: Negotiating Geography and Morality in Shi’ite South Beirut (Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 2013).

4 Joshua Salaam was the youth director at the time and helped mentor the youth in the Next Initiative. However, he would eventually leave ADAMS to become a director and chaplain at Duke University.

[4] For more on the tension between being “Muslim” and “American” as a young teenage boy see John O’Brien, Keeping it Halal: the Everyday Lives of Muslim American Teenage Boys (Princeton, New Jersey: Princeton University Press, 2017).

[5] As the authors of “Muslim Youth and 9/11 Generation” explain, “[i]nstead of giving rise to politically active movements around a shared sense of a history, the generational awareness among young Muslims in the aftermath of 9/11 has triggered a wide range of questioning, experimentation, processes of self-fashioning, and, occasionally, protests.” Moreover, “[b]efore 9/11 Muslim youths whose parents had immigrated to the United States frequently saw Islam as part of the taken-for-granted cultural heritage associated with their family’s country of origin, much like Buddhism, Hinduism, or Sikhism among other immigrants. In the aftermath of 9/11 and the subsequent war on terror, many of them felt compelled to confront the suspicion and ostracism that targeted them by enacting their Muslim identities more self-consciously and with greater self-awareness than before”; Adeline Marie Masquelier and Soares, Benjamin F. Soares, Muslim Youth and the 9/11 Generation (Santa Fe : School for Advanced Research Press ; Albuquerque : University of New Mexico Press, 2016), 6; Fait Muedini, “Muslim American College Youth: Attitudes and Responses Five Years After 9/11,” The Muslim World 99, (2009): 39-59.

[6] I was a board member and chair of the Youth Task Force at the time and introduced Ali to the idea of a youth center.