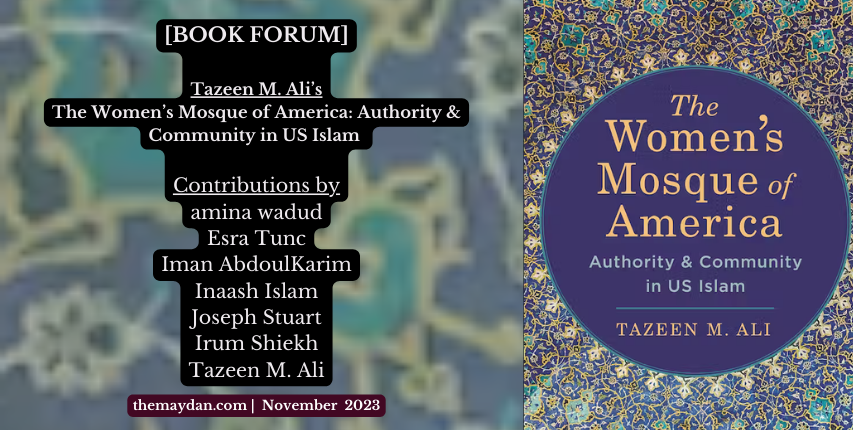

This forum brings six scholars into discussion with Tazeen Ali’s The Women’s Mosque of America: Authority and Community in US Islam. In line with the book’s main argument, the reviewers [amina wadud, Esra Tunc, Iman AbdoulKarim, Inaash Islam, Joseph Stuart, and Irum Shiekh] engage with Muslim women’s religious agency and interpretations of the scripture as commitments to social and racial justice. Tazeen M. Ali contributes to the forum with a response essay, engaging with the reviewers.

amina wadud

How thrilling to live to see changes in our Islam, as a way of life. How challenging for Dr. Tazeen Ali to provide a deeply critical and broadly insightful monograph on one aspect of those changes, in her book, The Women’s Mosque of America: Authority and Community in US Islam (NYU Press, 2022). Ali manages to capture one of the most inspirational aspects of the changes within our Islam today: the rise of Muslim women’s authority. Women’s authority in Islam impacts not only law and policy but also our devotional practices and the ways those practices reflect community and culture. Reading this book reminds me of my own experience and participation in the transformation of Islam, gender and women’s spiritual authority. All of this can be located under the heading of Muslim and Islamic feminism, which forms a foundation to Ali’s insightful, accessible and scholarly contribution to the conversation.

In particular, Islamic feminist scholars and activists insist on affirming Muslim women’s lived reality as part of a deeply transformative methodological shift. After more than a millennium of male-centered scholarly reflections, cultural praxis, politics and law, women’s lived realities have been constructed to prove their significance as markers of universal Islam. Those realities have transformed not only how we read sacred texts but also how we reflect the transformed understandings of those texts into policy and sacred performance. Although my intention in this short review is to specifically focus on the book, I must step back for a moment to also reflect on how I share in these most profound changes in the legacy and practice of Islam into this millennium.

My personal backstory of research and ethical advocacy brought both Tazeen Ali, the author, and Maryam Hasna Maznavi, the founder of the Women’s Mosque of America, to my doorstep in Northern California. Both visits were wonderful occasions to mark two important considerations on women and Islam today: that is scholarship and activism respectively. The founder shares both her first and second name with my eldest daughter. It made me feel like I was reading the “signs in ourselves and in the universe,” as the Qur’an compels us to do. I supported Maznavi’s idea to organize, transform and be transformed by a women-centered communal Friday prayer: salat-ul-Jumu’ah. She centers women’s leadership in all aspects of the Friday prayer.

The Women’s Mosque of America (WMA) began around the same time as two online initiatives helped to bring greater attention to women’s subaltern access in the dominant, mostly conservative, male-led mosques in the US: The “Un-Mosqued” campaign and the “Side Entrance” campaign led by Hind al-Makki. Both of these online movements provide clear evidence to the ways access for women in mosque participation and organization is limited. US mosques observe these shared community events centered on Cis-men and the male experience of the sacred. Prior to these online discussions, Queer and gender non-binary Muslim scholars and activists had already laid the foundation for the unconditional inclusion of women in all aspects of Islamic sacred worship. The modern women’s mosques movements followed these trends within a decade. WMA established itself as the first women led initiative that became and remains a reality in the context of the United States. Since 2015, the WMA Friday prayer meets once a month.

While I offered my support and consultation to Maznavi, I also offered to keep my name anonymous. Certain controversy surrounds my life’s work—especially accepting an invitation to act as Imam and Khatibah for the 2005 Inclusive prayer event. In her book, Ali reminds us how “earlier conversations” continue to negatively impact any kind of effort to center women in Islamic communal worship. Nevertheless, Ali’s book further confirms that there was no need for my anonymity because opposition to the Women’s Mosque “continu(ed) an often-hostile criticism” along the same lines as were levied against that 2005 one-time prayer event. On one hand, I think, of course the same arguments would ensue. After all, women’s subaltern spaces and lack of authority in mainstream conservative mosques remain mostly uncontested. On the other hand, I am concerned that the 2005 prayer event has become a glass ceiling for what is understood about the limits of women’s authority in Islamic ritual praxis and spirituality.

A few years after Maznavi’s visit, Tazeen Ali visited to discuss her on-site research into WMA in Los Angeles. She makes no reference to our discussion in the book, although we had a pleasant afternoon. I am thus all the more thrilled to see this book come to publication. It offers a critical look at the Women’s Mosque of America and the women who are part of that movement, as organizers, participants, khateebahs, imams and congregants. Ali’s analysis gives thorough and nuanced attention to the complexity of Muslim women’s authority in liturgy and community in the context of Islam as a minority community in North America. The internal process of directing gender relationships towards coherence and care cannot be completed in isolation from the politics and major discourses of the larger contexts under which those relationships are being built. Muslims in minority communities across the US and EU are heavily impacted by Islamophobia. It pervades all their lived realities and relationships with various levels from mild to extreme negativity. Perhaps this is one reason why confessional Islam in America is so peculiarly conservative, patriarchal, hegemonic and binary. Still, such Islam begs the question: how does one find a place within if one is not a cis-gendered heterosexual man?

Ali’s deep insights and critical analysis help us to consider the idea of women’s authority as it unfolds in women-led, women centered or women-only mosques. The book’s analysis is specific to the current context of Islam in America and therefore does not engage as much with a more comprehensive historical precedent or with such developments globally—including in Muslim majority contexts, like Indonesia, where I live. The existence of women-only mosques creates a peculiar controversy due to the backdrop of Islamophobia in diasporic Islam. The result is a parallel rise of patriarchal conservatism. We must consider such matters then, relative to a minority community whose greater sense of autonomy and integrity can only be measured within the dynamics of the way Islamophobia shapes the community. This point is brought out very clearly in Ali’s book and in some ways creates another level of coherence not only about WMA but about the larger matter of women’s authority, albeit in a specific context rather than in the context of global movements for reform. Since WMA—and all the other western initiatives to center women—comes on the heels of the inclusive mosque initiatives that had already spread globally, I cannot help but think about how the LA movement aligns within that larger framework when we seek to question exclusive cis-male authority. Inclusive mosques have confirmed women in the role as imams, mu’adhan and khateebahs, along with Queer trans, and other gender non-binary members. This is not a central focus of Ali’s book and I wonder how that might shape different arguments and critical analysis about challenging entrenched patriarchal authority.

One aspect of Ali’s focus on women’s authority is the emphasis on using English by the women who deliver the Friday sermon, the Khateebahs, and for interpretation of the Qur’an. I wanted to consider the use of English a secondary concern, since it is merely the language of the context. However, Ali points out the ways in which using English was encouraged by the organizers as they also encourage women to align their personal experiences with—or even over—sacred texts. This book made it clear to me how the dynamism of Islam in the US and amongst the women who identify as American Muslims therein, were necessarily aligned to bring currency to the use of English as a mechanism of interpretation. English is then developed into part of a methodology which highlights lived realities as instrumental to interpretation. Indeed, the precedent was set by the content of the first khutbah in 2015 by Edina Lekovic.

I had never considered how the use of English might itself be an act of resistance to the extent to which Ali brings it to my attention when she traces the developments of WMA. In one way, all interpretations are rendered from the lived realities of the interpreters. Unfortunately, the dominance of men in these sacred roles has led to the false notion that the male experience is in fact universal and comprehensive. Islamic feminist scholarship has emphasized the negative impact of leaving female experiences out of concepts used to construct the basic paradigms of Islamic fundamentals. Thus, I especially appreciate Ali’s assertion that a singular emphasis on Arabic to affirm authority is a form of racism. She brings an even deeper critical assessment to the priority given at WMA to transform the ways that non-scholars are also authorities.

Ali describes WMA as multi-racial with an emphasis on intra and interfaith solidarity. This provides an ethical alternative to hegemonic mosque spaces rooted in maleness. Many mosques in America are organized around cultural variants of the US Muslim population over and above sectarian variants. Ali observes that while textual engagement is often used to equal legitimacy, if not also authority, most women do not engage with mere textual analysis in their khutbahs, except to emphasize personal narratives. Here, she unveils a new model of authority. A model which allow khateebahs, congregants and board members to support a women’s right to lead. I had not come across this way of looking at the matter – it helps lay bare how the foundational conceptualization of Islamic legitimacy was so narrowly constrained by historical and cultural ideas of what constitutes Islam.

Indeed, engaging English translations to interpret the Qur’an through self-reflection and personal experience is an aspect of the social justice insisted upon within the text. In this matter I tend to defer to Khaled Abu el-Fadl’s emphasis on both textual competence as essential to authority as well as an ability to transform community by the mere existence of certain experiences. In this respect I made a leap in my own understanding assisted by Ali’s critical examination. It is not merely experiences and lived realities that are a measure of authority. However, those experiences when given authority and legitimacy work in tandem with textual analysis and legal authority in a kind of dialectic. This is implied by Ali’s lengthy engagement with the question of authority, although not in a way that was previously clear to me. Ali provides an examination of activism in process. The legal and ethical considerations are present albeit not emphasized. Ali helps bring greater respect for the criteria WMA uses for choosing khateebahs. They are not chosen based upon their knowledge of the traditions alone. Instead, WMA’s method emphasizes experiences as a sufficient basis of legitimacy.

It is delightful and fascinating to read how ideas about women’s vulnerability act as agency. This vulnerability is emphasized—even requested—by the organizers in their 16-page guidebook. I find the guide to be equally authoritative, a distinction from authority as defined by al-Fadl. It limits who can participate as well as how they participate by providing strict parameters on the common denominator of informal or missing expertise in Islamic Intellectual traditions. As Ali points out, this is an instance of women subverting other standards of authority and women’s selective acquiescence and resistance. She bases this on an analysis of Protestant women in the Black church. She also points out the double liminality of WMA organizers and participants in relation to their male cohorts in the larger US context.

At WMA, authority is shared between congregants and khateebahs in a dialogue. Indeed a great equalizing practice. There is attention drawn to how a separate space run by women contrasts with so-called mixed spaces where women are not only separated but men are privileged. She suggests this provides a stronger sense of community as expressed by several of her interviewees. They say WMA provides them with opportunities to learn more than in the conservative mainstream mosque settings which are still limited or restricted to women.

The scope of Ali’s analysis helped me to see more into the current dynamics of activism in the US, something I have held no role in since the new millennium. I would be further interested to know the demographics of MWA and how many organizers and khateebahs are born in the US. Is there a generational component to how WMA organizes itself? If so, those born in the US have an even greater stake in how authority and spirituality is performed in their context.

The opportunity to review the book and reflect on Muslim women’s global movements was for me greatly beneficial. Ali brings an insightful, interdisciplinary, critical analysis to an already exciting reflection of women’s agency and authority as is the goal of the Women’s Mosque in America.

Dr. amina wadud is a world renown scholar and activist with a focus on Islam, justice, gender and sexuality. After achieving Full Professor she retired from US academia—except as Visiting Researcher to Starr King School for the Ministry, California, USA. After 15 years in retirement she served as Visiting Professor at the Post Graduate Studies Program National Islamic University Sunan Kiljaga, in Jogjakarta, Indonesia. She migrated to Indonesia in 2018 to avoid the chaos of US politics and ethics first hand. Author of Qur’an and Woman: Rereading the Sacred Text from a Woman’s Perspective, a classic that helped towards the development of epistemology and methodology in Islamic feminism, which is the most dynamic aspect of Islamic reform today. It is 3 decades old and translated over 10 times, most recently into French. Her second manuscript, Inside the Gender Jihad: Women’s Reform in Islam, moved the discussion further by aligning it with a mandate for ethics and activism in collaboration with scholarship and spirituality. A recent memoire Once in a Lifetime

After completing a 3 year research grant investigating 500 years of Islamic classical discourse on sexual diversity and human dignity, funded by the Arcus Foundation, she is organizing an International Center for Queer Islamic Studies and Theology: (QIST) the first of its kind in the world. Mother of five and Nana to six, she is best known as The Lady Imam.

Esra Tunc

Tazeen Ali’s book is an ethnographic account of how Muslim women construct religious authority within the Women’s Mosque of America (WMA) in Los Angeles. Unlike many mosques in the United States and around the world, where men typically hold authoritative roles and the primary prayer spaces are reserved for men, the WMA exemplifies a unique model of gendered authority. In the WMA’s model, women lead prayers and interpret Quranic verses, and their interpretations of the Quran rely on English translations, questioning the expertise in the Arabic language as a prerequisite for Quranic interpretation. This model considers women’s experiences, such as their struggles and vulnerabilities, to be valid sources for making religious claims. Similarly, in a departure from US Muslim imaginations of Islamic authority in Muslim-majority contexts, the WMA puts the United States at the center in debates on Islamic tradition. The WMA also operates as a space where congregants can initiate conversations about racial and gender justice–related issues and create bonds of community across different religious, racial, and ethnic backgrounds. In light of Ali’s valuable insight into the bigger picture surrounding questions of race and gender in US Islam, this review focuses on the WMA’s intersectional approach to challenging various forms of domination.

Ali’s book draws on Black feminist and womanist frameworks, which include not only the scholarship and activism of amina wadud, Debra Majeed, and Patricia Hill Collins, but also the stories of Black Muslim women who were key participants in the WMA. By doing so, Ali demonstrates how the construction and performance of gender is connected to various intersecting authority structures, including cultures of patriarchy, Islamophobia, and anti-Black racism. Examining how the WMA stands in relation to these forms of domination, the book pays special attention to attempts to be inclusive of social and religious differences. One example is the way the WMA navigates the controversial question of women’s prayer leadership. The mosque’s aim is to include every dimension of Muslim legal debates about whether women can lead Friday prayers. To welcome those who discredit women’s prayer leadership, the WMA board members have added an optional dhuhr prayer to their schedule of Friday prayers at the mosque. Ali reads the attempts to include different Islamic interpretations as “pragmatic” because, to Ali, the attempts exemplify how board members at the WMA refuse to be limited by the controversy that surrounds women’s prayer leadership (41). While the ways the WMA members connect themselves to previous models of women’s prayer leadership can be questioned, Ali’s interpretations encourage us to recognize the broader social and cultural dynamics that lead to these debates, and to examine how a person’s recognition as a legitimate leader is shaped by race, gender, and ethnicity and by claims about proximity to classical Islamic sources. For example, Arab Muslims or Muslim authority figures who claim to be connected to conventional wisdom are often considered legitimate religious leaders in the eyes of Muslim public (53). However, the WMA members help us think more broadly about religious authority as they demonstrate how lay Muslim women from different racial and ethnic backgrounds can practice religious authority without having formal Islamic education.

Another example that can help us develop a critical perspective on inclusivity is related to interfaith engagements at the WMA. Women at the WMA not only build allyship with women in other faith traditions but also work towards intrafaith inclusivity. However, Ali provides a critique of the complexities that are embedded in interfaith engagements. For example, Ali notes that those from outside the mosque who participate in interfaith engagements at the WMA are mostly white interfaith allies who are mostly followers of Judaism and Christianity. With this observation, Ali encourages the reader to think about how American pluralism is connected to imagining a community that creates a sense of American exceptionalism tied to white Protestant hegemony.

Ali’s central argument—that these women create an Islamic authority through their participation in a women’s mosque and their interpretation of scripture—offers insight about different ways religious authority can be implemented. In particular, several points throughout the book encourage readers to think about how authority operates among different members of the WMA. One crucial example is the various ways the founder and board members at the WMA exercise power. For example, khateebahs (female preachers) need to send their khutbahs to the board members, and the board has the power to edit these khutbahs. While khateebahs have different reactions to the editing process, Ali interprets this process as a form of a mentorship and guidance between the WMA board and its khateebahs.

Ali’s intersectional approach to the forms of domination that shape the WMA also points to ways to explore class in Muslim spaces and beyond. Ali informs us that the WMA often prefers to give a platform to professionally accomplished Muslim women, such as “entrepreneurs, activists, doctors, community leaders, or professors” (200). Why does the WMA give the role of religious authority only to professional Muslims—that is, to “empowered” Muslim women? I suggest that excluding non-professional Muslim women from roles of religious authority might replicate one particular issue that surrounds US mosques: they are segregated based on the socioeconomic conditions of their neighborhoods, which is the result of the interconnection of race and class. In that regard, one may ask: How does the WMA respond to the presence of Muslim communities, such as the one in South Central LA, that are at a significant socioeconomic disadvantage with respect to other communities? While the WMA khutbahs that Ali examines in the book do not directly discuss issues connected to class, Ali hints that the WMA members may join other groups that are deeply concerned about Los Angeles’s issues, such as Clergy and Laity United for Economic Justice (CLUE) (224-226), although Ali also notes that “Muslim involvement in CLUE is sparse compared to its Christian and Jewish affiliates” (227). The WMA’s exclusive selection of professional Muslims as khateebahs also raises a question: how radical is the WMA? To what extent does the WMA challenge the status quo?

Throughout the book, Ali deftly situates the WMA at the junction of the historical and global factors that shape Islamic authority and the development of US religions. Walking us through the various ways US Muslim women navigate domination by performing roles of religious authority, Ali’s book is a crucial intervention at a time when mainstream mosques and certain religious authority figures are joining in right-wing discourses about gender-fluid bodies. Ali’s book demonstrates that these bodies can also claim Islamic authority through various authority structures by contributing to Islamic legal debates and interpretations of the Quran and by focusing on their bodily experiences. Ali’s careful attention to the discursive practices at WMA helps us situate the WMA within broader debates in both Islamic Studies and among Muslim communities at large, not only by demonstrating the importance of studying non-Arab subjects and non-Arabic sources but also by contributing to conversations about racialized and gendered subjects and traditions.

Esra Tunc is an assistant professor in the Department for the Study of Religion at San Diego State University. She earned her Ph.D. in Religious Studies from the University of California, Santa Barbara. Her research focuses on Islam, racial capitalism, and forms of relationality. Her book project, “Unjust Capital: Muslim Investing in the United States,” examines the innovation of financial capitalism among Muslim communities in the United States.

Iman AbdoulKarim

When it comes to religious authority in the U.S., terms like maleness, learned elite, political conservatism, hierarchy, and top-down influence over the community are likely to frame the conversation. Hegemonic profiles of religious authority in U.S. Muslim communities take on a distinct, but related profile: maleness, Arabic language expertise, and formal credentials obtained from institutions located outside of the U.S., as noted by Ali. However, The Women’s Mosque of America: Authority & Community in US Islam (2022) offers a clear-eyed, nuanced analysis of distinctly feminine forms of authority shaping the first women-led mosque in the U.S., established in California in 2015. Based on a textual analysis of khutbahs delivered by lay and non-lay Muslims paired with ethnographic interviews with WMA congregants, Ali demonstrates that terms like embodiment, emotion, professional credentials, vulnerability, nurture, activism, intimacy, and lived experience are crucial for understanding what and who is recognizable as an authority on Islam in America. As Ali argues, this new lexicon for understanding religious authority in U.S. Muslim communities is not meant to replace the hegemonic forms of authority noted above; rather, it delineates how the WMA extends and imagines beyond them.This new profile of religious authority could not be a timelier contribution to the study of Islam and U.S. Muslim politics. Ali’s first book gifts readers, especially those committed to thinking with and studying Islam beyond its most hegemonic forms, a necessary rebuttal to those scholars and thought leaders who hold onto mono-dimensional representations of Islam and out-of-touch renderings of U.S. Muslim concerns to police the boundaries of what it means to be Muslim, study Islam, and name U.S. Muslims’ relationship to contemporary U.S. politics. Boundaries that align with, rather than see beyond the gendered and racialized notions of authority and citizenship. Paying particular attention to Ali’s formulation of “embodied authority” and “authority through activism,” the below highlights how Ali’s work encourages readers to deeply reflect on the intersections of gender, Blackness, and religious authority in their understanding of the WMA, American religion, and global debates about Islamic authority.

Ali’s work is structured around a straightforward typology that parses what is broadly glossed as “religious authority:” ritual authority (Chapter 1), interpretive authority (Chapter 2), embodied authority (Chapter 3), and authority through activism (Chapter 4). Ali repeats that these forms of authority, which the WMA fosters in lay and non-lay Muslim women, did not emerge onto the U.S. religious landscape with the advent of the Mosque in 2015, nor are these forms of authority unique to the WMA. However, the WMA is unique in that it consolidates these forms of authority within a single community and cultivates them amongst lay and non-lay Muslim women as they deliver kutbahs, bayans, and lectures at the Mosque. The culmination of these forms of authority in a single space offers a unique opportunity, Ali argues, to understand the WMA as an extension of practices that can be found in reformist movements in Egypt, a part of the genealogy of African American religious history, and a continuation of U.S. Black feminist thought within U.S. Muslim communities. Through this framing, Ali (a) pushes readers to understand the WMA beyond simplistic portrayals that story the WMA as formed in resistance to male-led, exclusionary spaces and (b) argues that U.S. Muslims are at the center, rather than the periphery of American religion and global debates about Islamic authority.

What is most exciting about Ali’s analysis of the WMA, for those interested in thinking with the categories of Islam and Blackness, is how she traces the intersections of the terms. As Ali details, WMA leaders include a group of Black Muslim women who sustain the nurturing community which congregants find unique to the space (137-50) and were instrumental to the establishment of the Mosque in 2015. However, Ali does not simply analyze the intersections of gender, Blackness, and Islam based on demographics. Rather, she draws connections between Blackness and Islam at the level of ideas, specifically the WMA’s use of “embodied authority” and “authority through activism.” The WMA encourages khateebahs to draw on their lived experiences, vulnerability, and emotions to interpret Qur’an verses and hadith on issues they’ve been personally impacted by; for example, sexual violence and gendered abuse. By centering lived experience as a site of knowledge, the WMA grants lay Muslim women embodied authority over religious texts. A form of authority that serves as an alternative to Islamic legal frameworks and approaches lived experience as a credential more authoritative than formal educational training that, say, an imam or other male religious authorities might rely on to interpret the same texts (129-130). Ali reads the WMA’s use of embodied authority as an extension of Black feminist thought theorized by Patricia Hill Collins. As Ali points out, by drawing on Collins, Black feminist thought has long distinguished between knowledge and wisdom (knowledge + experience) and emphasized emotion, empathy, and personal character to asses truth claims (128-130). Ali frames the WMA’s use of embodied authority as an expression of “Muslim womanism,” a school of thought coined by Debra Majeed that applies Christian womanist ethics to Islamic contexts, positions everyday Black women’s experiences as authoritative sources for interpreting Islamic texts, and enables lay Black Muslim women to establishes their own legitimacy over Islam (126-127). By contextualizing “embodied authority” as an extension of Black feminist epistemologies, as named by Collins and Majeed, Ali frames the WMA as a space in which Black feminist thought is applied to contemporary Muslim contexts. Ali makes clear that a complete rendering of the WMA (a) necessitates understanding how the WMA’s is in conversation with Black schools of thought that have long determined what constitutes knowledge, justice, and authority on their own terms; and (b) Black feminist/ radical thought’s inability to be placed neatly on either side of the religion vs. secular or religion vs. politics divide. As Black radical thought and critical race theory continue to be attacked and outlawed in the U.S., naming and analyzing the impact of Black feminist thought in spaces where it might not be anticipated is more important than ever.

Ali extends her analysis of WMA’s relationship to U.S. Black history and thought in her analysis of khateebahs’ use of “authority through activism.” Ali places the WMA’s use of “authority through activism” in the genealogy of African American religious history, which is American religious history. With precision, Ali details how the WMA functions as a multiracial discursive space for grappling with U.S. social concerns (186-187), including racial and gender equality, U.S. anti-Blackness, and the Black Lives Matter movement. Khateebahs lean into their professional credentials and activism to bring Islamic texts to bear on contemporary issues like police violence and mass incarceration. In doing so, they cultivate an “authority through activism” and legitimate their social-justice readings of the Qur’an as an authentic reflection of core Islamic teachings (189). Ali tracks how WMA constructs, with various degrees of success, a shared American consciousness based on social justice issues. In doing so, the Mosque encourages congregants to speak authoritatively on such issues within the Mosque and in the everyday spaces they inhabit. Ali contextualizes the social and political dimensions of the WMA as reflecting the kind of organizational aims that can be traced back to Black women’s activism in Baptist churches in the late nineteenth century, as historicized by Evelyn Higginbotham. Like the women-led activism found in Black church histories, the WMA aims to develop a national consciousness amongst its congregants and mobilize that consciousness to generate collective American Muslim interest on issues like anti-Blackness within and outside of Muslim communities (187). Ali’s framing places the WMA in the genealogy of African American religious history, where houses of worship have always been, in the words of one khateebah, “more than a place of prayer,” (187). In doing so, Ali uses the categories of race and Blackness to name what is definitively American about the organizational structure and aims of the WMA. In other words, Ali centers Black religious history and thought to name what is American about the WMA – a genius framing that challenges the idea that the WMA’s “authority through activism” should be understood as a new phenomenon marshalled exclusively in resistance to the prototype of the oppressed Muslim woman, rather than a continuation of the blurring between the religious and political that has characterized U.S. Black women’s history. In doing so, Ali’s work encourages readers to consider how race, Black thought, and African American religious history influence religious authority in contemporary U.S. Muslim communities and shape, whether named or not, its influence on global debates about Islamic religious authority.

Ali’s accessible writing, concise summaries of literature, and typology of feminine forms of religious authority make The Women’s Mosque of America a must-read for anyone interested in the intersections of race, religion, and gender. As scholars of Islam continue to grapple with how to do race, think with Blackness, and engage Black Studies, Ali’s framing of WMA in conversation with Black feminist thought and African American religious history offers an important example of how to meaningfully carry out such work.

Iman AbdoulKarim is a Ph.D. candidate in the Department of Religious Studies and Department of African American Studies at Yale University. Her research interests include Islam in America, African American religious history, Black feminist theory, and race and gender in Islamic thought. Her dissertation project centers the lives and legacies of twentieth-century U.S. Black Muslima thinkers to probe the relationship between Islam, Black radicalism, and secularism in the U.S.

Inaash Islam

What does it mean for Muslim women to cultivate and legitimate their own religious authority? What can we expect when Muslim women choose to create their own spaces of worship, and engage in the Islamic discursive tradition through a gendered and racial lens? Tazeen M. Ali’s insightful book, The Women’s Mosque of America explores such questions and more. In examining the Women’s Mosque of America (WMA), a multiracial, woman-led, intrafaith and interfaith mosque located in Los Angeles, Ali illustrates the radical and beautiful resilience of Muslim American women as they contest women’s historical marginalization from Muslim spaces and the hegemony of patriarchal interpretive traditions that do not align with their social realities as women.

Written in wonderfully accessible language, this book explores the emergence, politics, model, and ethics of the WMA. In five chapters, Ali explores the WMA using data from ethnographic participation observation at the WMA, interviews with its congregants and khateebahs, and a selection of khutbahs delivered from 2015-2021. Her analyses of this data are situated in, and draw from several theoretical and intersectional frameworks stemming from religious studies, Black feminist thought, Islamic feminism, sociology and beyond. As a sociologist who studies the implications of anti-Muslim racism on Muslim American women, I especially appreciate Ali contextualizing the WMA’s politics and cultivation of authority within broader frameworks of anti-Muslim racism and gender injustice in Muslim spaces. This contextualization is key to illustrating the challenges that Muslim American women face when navigating the double bind of racialized sexism and gendered racism in the US. Indeed, it is frustratingly difficult to critique issues of gendered injustice experienced in Muslim communities – which are often legitimized through patriarchal interpretations and understandings of Qur’anic texts and Hadith – without giving ammunition to Islamophobes in the current climate.

Three of Ali’s chapters deal with the issue of authority, offering readers a nuanced analysis of internal Muslim debates on women’s claim to religious authority in its various forms. Ali unpacks the concept of religious authority into three categories: Ritual Authority, Interpretive Authority and Embodied Authority. The chapter on ritual authority describes how the WMA has responded to internal and external criticisms of the Islamic validity of women leading Jummah prayer. Ali illustrates the diplomacy of WMA’s organizers and khateebahs in providing their congregants with textual evidence of women leading women in prayer, as well as an optional Dhuhr prayer for those members who regard woman-led Jummah as Islamically invalid. In reflecting on the WMA’s engagement with the Islamic legal tradition, I am thrilled to see Muslim women directly engage with Islamic legal argumentation, and contribute to shaping an inclusive and intrafaith public religious space that caters to all. Thus, not only does Ali show that the WMA is shaping the “trajectory of community conversations on Islamic authority, and more broadly on the form and function of mosques in meaningful ways” but she also shows the potential that women have in creating pluralistic communities when they have full seats at the table (48-49).

I especially love Ali’s chapters on interpretive and embodied authority, given that they provide empirical points of departure for the gendered practice of Ijtihad (Islamic legal reasoning). With the resurgence of Ijtihad in recent decades, there is a renewed recognition that one’s standpoints and social realities have a deep impact on how one understands, engages with, and applies religious texts in life. Lay Muslims especially have been engaging in Ijtihad in efforts to reconcile the cognitive dissonance that they experience in their contemporary social realities with what they have been taught about Islam by their families, religious leaders, and Islamic schools. In her chapters on interpretive and embodied authority, Ali illustrates how the WMA engages in Ijtihad to not only legitimate the ritual, interpretive, and embodied authority of women, but also provide its congregants with an understanding of the full experience of Muslim womanhood as rooted in Islamic history and tradition. In fact, Ali’s choice to begin the text with Kennard’s unease with polygamy in the Islamic tradition beautifully illustrates the book’s exploration of the WMA’s mediation of gender and authority through Ijtihad.

The use of Ijtihad to center and discuss domestic violence, the loss of a child, divorce, and other issues of significance that affect Muslim women illustrates the deployment of Islamic feminism at the WMA. Although Ali is careful to state that she does not label the WMA as Islamic feminist, nor does the institution identify itself as feminist, in my reading of Ali’s analysis, the WMA’s model, legitimation of khateebahs’ religious authority, and content of khutbahs arguably fit within broad conceptions of Islamic feminism. In fact, the WMA’s institutional position on the Qur’an affirms it as a gender-egalitarian text (109), and several of its khateebahs have discussed contentious patriarchal verses in the Qur’an through Islamic feminist frameworks. Ali describes the involvement of scholars like Omaima Abou-Bakr and Abla Hasan, who offered khutbahs entailing anti-patriarchal re-readings of critical verses like 4:34 at the WMA. In using Ijtihad to employ exegetical moves to contest patriarchal readings of Qur’anic texts, khateebahs like Abou-Bakr and Hasan provide congregants with the tools to engage in Islamic feminist forms of Ijtihad that potentially increase their everyday embodied autonomy, religious knowledge, and confidence to affirm Islam as a gender-egalitarian religion in light of gendered Islamophobia. In recognizing the manifestation of Islamic feminism within the WMA, I would go so far as to say that Ali’s book is one of the first contemporary works to illustrate the empirical potentials of Islamic feminism in the United States.

Ali’s discussion of how gendered, lived experiences serve as the criteria that validate khateebahs’ embodied authority, prompted me to reflect on the (in)visibility of gender in the khutbahs that I have heard delivered by male imams in gender segregated Sunni mosques. Not only have these khutbahs rarely (if ever) been directed at me or my Muslim sisters, but the content of these khutbahs understandably stem from male imams’ gendered experiences and standpoints. In my experience, even when these khutbahs refer to Muslim women, Muslim womanhood is only ever addressed in relation to others – i.e., we are addressed as mothers, daughters, sisters, and wives – as beings who can reach our ‘divinely-intended’ potential through who we are in relation to others. Ali shows that the WMA’s khateebahs however, draw from their own gendered embodied experiences to deliver khutbahs with nuanced understandings that emphasize the full humanity of women, rather than focusing simply on who women are in relation to others. Ali states, “WMA members not only privilege women’s experiences in interpretations of the Qur’an but also posit that men lack the insight to speak on certain subjects with nuance” (111). By exploring themes of grief, loss, joy, courage, hopelessness, and autonomy, among others, WMA’s khateebahs offers congregants nuanced understandings of Muslim womanhood that exist both in relation to, and beyond who they are to others. Thus, given Ali’s in-depth analysis of embodied authority, I am heartened by her interviewees’ positive reception of the WMA, its khateebahs, and khutbahs, as these provide Muslim women with the religious education, gendered epistemology, and supportive networks that Ali’s interviewees describe as lacking in mainstream Muslim mosques headed by male religious authorities. This is a testament to the WMA’s ability to serve the spiritual and social needs of Muslim women and, by extension, the broader Muslim American community.

In her fourth and fifth chapters, Ali provides us with an in-depth analysis of the WMA’s commitments to social justice, activism, and multiracial and interfaith solidarity. She shows that in placing Islamic scripture in conversation with issues of social justice and solidarity, khateebahs not only cultivate activist authority, but are also at the forefront of emergent trends of forging intersectional, interfaith, and intrafaith alliances in religious spaces. I find these two chapters particularly illuminating for several reasons. First, given the demographics of WMA attendees, for each member to navigate such a diverse space requires the establishment of a framework of understanding that is fundamentally pluralistic. The WMA’s organizers and khateebahs appear to have done an incredible job developing a pluralistic, and more importantly, deliberately non-judgmental framework that resists social hierarchies, builds community, and inhibits the gendered policing of women’s bodies and religious practice. For example, Ali discusses how the WMA’s intrafaith approach to solidarity involves providing Shi’a congregants turbah with which to pray, inviting khutbas from khateebahs with diverse backgrounds (including the Nation of Islam and Sufism), and instituting rules that inhibit congregants from policing each other’s clothing and religious practice (e.g. some women choose to pray without the hijab). The importance of this pluralistic approach is made salient by the fact that not only are Muslim Americans from minority sects systematically marginalized from mainstream mosques, but the overt and subversive policing of Muslim women’s bodies and religious practice in mainstream Muslim American communities is one of several critical factors causing the current exodus of Muslim women from their faith communities. For example, sociologist Eman Abdelhadi’s forthcoming book, Impossible Futures: Why Women Leave American Muslim Communities While Men Stay, describes how gendered policing – among other factors – plays a key role in this exodus, as well as in the decline of women’s religiosity and religious practice. Thus, Ali’s description of the WMA’s inclusive and pluralistic framework is not only timely given this current crisis, but also insightful in that it provides other Muslim American communities with a framework of inclusivity that retains congregants.

Ali’s final two chapters are illustrative of the WMA’s potential to address another concern facing Muslim America: the decline in Muslim youth’s mosque attendance. A report by the Institute for Social Policy and Understanding (2020) finds that “mosques are not attracting a significant percentage of Generation Z and young Millennials” (n.p.). Although this trend is in line with other faith traditions in America, we have yet to collate data on the specific reasons for this decline (Gallup 2021). That said, news reports and op-eds in recent years give some insight on this issue, pointing to Gen Z’s ideological commitments to social justice activism, and religious leaders’ lack of understanding and engagement with issues of social justice that involve race, gender, sexuality, religion, and nationality (Kennedy 2015). In Minnesota for example, young Somali Muslims feel that local community leaders and imams are not only uninvolved in pressing issues of social activism like Black Lives Matter, but also lack the insight, education, and inclination to speak on these issues through religious frameworks (Hirsi 2017). In thinking about the possible reasons for this decline, while also acknowledging the gendered burden Muslim women face as the assumed reproducers of religion and culture in Muslim America, we can better appreciate the significance of women’s claim to religious authority at the WMA. Specifically, the religious education that Muslim women receive, their engagement in Ijtihad, their role as agents of religious socialization, and their ability to create pluralistic, spiritually-nourishing, and meaningful spaces for dialogue on issues of Islam and social justice illustrates the critical role that Muslim women play in shaping the future directions of Islam in America. Therein lies the radical significance of the WMA.

Suffice to say, Tazeen M. Ali’s book provides readers with an incredibly rich, well-researched, accessible, and thought-provoking analysis of L.A.’s Women’s Mosque of America. Her nuanced analysis of religious authority compels readers to reflect on ways by which Muslims use the category of gender to discursively uphold and resist the marginalization of valuable sources of religious authority. In analyzing the conception, emergence, model, politics and ethics of the WMA, Ali makes it abundantly clear that the frameworks of the WMA emerge from within the Islamic discursive tradition, rather than outside of it. Acknowledging this is empowering for lay Muslims and mainstream Muslim communities that endeavor to validate Muslim women’s religious authority, create affirming and pluralistic spaces for worship, and address contemporary crises affecting Muslim America.

Inaash Islam (she/hers) is an Assistant Professor of Sociology at Saint Michael’s College. Her research focuses on the post-9/11 implications of anti-Muslim racism, gendered racialization, and Islamic feminism in the lives of diasporic Muslim women in America. Her current book project examines the experience of unveiling/taking off the hijab among formerly-hijabi Muslimah Americans, and illustrates the ways by which Muslim women are employing Islamic feminisms in their everyday lives. She also has a forthcoming co-authored book on global anti-Muslim racism with Dr. Saher Selod and Dr. Steve Garner entitled A Global Racial Enemy: Muslims and 21st-Century Racism, and has published her research in Du Bois Review, Feminist Formations, and the Journal of Arab and Muslim Media Research.

Joseph Stuart

The Women’s Mosque of America: Race, Individualism, and Community

Tazeen M. Ali’s The Women’s Mosque of America: Authority and Community in US Islam is a brilliant and complex work that provides new ways for scholars and Islamic practitioners to understand how and why Muslim women in the United States find meaning in all-female spaces. She examines how the WMA’s community interprets and reinterprets Muslim traditions and creates gendered and racial forms of authority that many Muslim communities struggle to address or implement. Ali shows that the “shared histories of Black and non-Black Muslims in America” come together in the WMA, whose multiracial congregations foster opportunities for interracial cooperation through shared appeals to Islamic texts, ethics, and authority (153). They do this without downplaying the difference in WMA participants’ racial and ethnic backgrounds, ideas about gender, acculturation, and other sensitive topics.

As my part of this group of reviews, I will concentrate on how the WMA fosters social justice initiatives across racial lines. In doing so, I address how Ali analyzes the balance between individualism, ethnic identity, and Muslim identity in the WMA.

The WMA serves Muslim women from many racial and ethnic communities, including African American (Black), Asian, Latinx, and white Muslims. Their diverse backgrounds, experiences, and expectations foster spaces where each group contributes their approaches and historical knowledge of social justice movements in the United States. Their disparate identities and expectations could lead to fracture.

For instance, relationships between African American Muslims and “immigrant” Muslims can be antagonistic. Many Black American Muslims view immigrant members of their faith (a term used by Ali to “broadly signify” WMA members’ ethnic backgrounds and how long their families have been in the United States) as subjugated through patriarchy and claim that they do not stand up to their male leaders, elders, and husbands in the ways that African Americans do (154). They also reject immigrants’ acceptance of anti-Black racism and label them as too trusting of the “model minority” trope, believing that their behavior and adoption of white American norms will lead to their acceptance and inclusion in the United States. Accordingly, they did not see a reason to support the WMA and expressed skepticism that separating religious worship services into a women-only congregation would lead to net positives for Muslim women.

African Americans were skeptical of the WMA’s aims and purpose until they recognized it as a site where they could serve as “mentors and models” for younger Muslim women. It was not only supporting Muslim women but the chance to help build multiracial Muslim communities in support of gendered and racial justice that won them over. Black women could share their knowledge of what the government had done to Black Americans like members of the Nation of Islam (NOI), the Black Panthers, and other groups committed to creating a more just world. In doing so, these Black women modeled longstanding community-building political activities in African American communities through religious organizations.

I appreciated that Ali shows that total agreement on topics as important as activism, gender, class, and acculturation can be catalysts to community building as much as barriers. Black women’s individual and collective opinions on immigrant Muslim women and disagreement over politics, gender ideologies, and other concerns do not prevent Black women from worshipping at the WMA. They find meaning in holding community with other Muslim women—their Islamic identities bring them together more than their racial identities.

Ali also examines how the WMA’s female khateebahs connect anti-Black racism in the United States and European anti-Muslim imperialism in ways that American Muslims have not always done, despite their historical overlap. This helps women of all racial and ethnic identities to connect with a message, although perhaps in a different register than the women worshipping next to them. For instance, in a July 2015 khutbah, South Asian khateebah Zahra Billoo connected the FBI’s targeting of the Nation of Islam in the 1950s to more-recent bombings of Yemen and Somalia to preach the need for persistence in the face of Islamophobia. In doing so, Billoo connected the violence and trauma that diverse Muslim women’s communities have survived in the past. She simultaneously draws upon the Qur’an and the authority derived from her career in social justice to address present events when she prayed that Allah would “forgive all those who have been unjustly killed by racist police officers.” In sharing examples from the past, other continents, and contemporary events, Billoo provides a framework for minimizing differences and maximizing the WMA’s shared Islamic identity.

Ali shares other examples of how WMA women connect through worship and fellowship, including opposition to sexist narratives of Muslim women and other social justice concerns. This reinforces religious identity despite differences, highlighting how a shared understanding of Islamic texts can collapse the distance between African American and immigrant Muslim women, building a sense of unity and purpose. The WMA’s khateebahs frame Islam “as a means to address modern injustices like institutional racism, police brutality, lack of affordable housing, and environmental degradation” (171). In doing so, these women articulate what scholars like Marie Griffith, Judith Weisenfeld, and Ula Taylor have also argued: women create meaning, wield power, and create authority through the logic and structures of their religions—because of their religious frameworks and not in spite of them.

Ali’s careful attention to showing how religious solidarity works does not mean that she homogenizes religionists’ political views or suggest that they agree on tactics, even if they have shared experiences or fears of violence and discrimination. The WMA does not advocate any particular political platform. Still, it encourages its congregants to participate in civic matters, which provides a multiplicity of expectations for how khateebahs should address specific political actions. Declining to set out a political agenda opens up space for broad conversations, such as the WMA’s 2016 discussion series on the Black Lives Matter (BLM) Movement. The series did not meet every participant’s expectations. Analyzing her interviews, Ali identifies three broad reactions to the discussion series: a group that felt it was a good idea but did not lead to action; those who were disappointed that it did not go further; and those who “were proud and mostly satisfied.” The divisions reveal how race and racial justice activism affect one’s relationship to religious and political identity, but also the reality that individuals do not need an organization to affirm every aspect of their identities to be meaningful or to create connections with others. Individual practitioners are often willing to downplay their disagreements when they find value within a community. Unity, as Ali shows, requires elevating the ideas they share rather than what could tear them apart without abandoning individual preferences.

While emphasizing the inclusiveness of WMA, Ali sometimes glosses over some of the tensions between groups. For instance, the WMA’s khateebahs sometimes quote American Muslim leaders like Malcolm X (El Hajj Malik). This, in and of itself, was not especially surprising, given that Malik converted to Sunni Islam before his assassination. However, quoting Elijah Muhammad (who had led the NOI for more than forty years before his death in 1975) and W.D. Mohammed (Elijah’s son and the founder of the World Community of Islam), seemed much more transgressive. As a historian of African American Islam, specifically the Nation of Islam, I was torn by Ali’s brief discussion of Malik’s, Muhammad’s, and Mohammed’s inclusion as Islamic authorities. While they hold sway in Muslim and non-Muslim Black communities for their social activism, their heterodox beliefs, ritual, and appeals to authority often marks them as not “authentically” Islamic to Sunni or Shi’a Muslims. I appreciated that Ali did not view their inclusion as requiring a long explanation for why the WMA accepts them as Muslim authorities. But it also would have been helpful for Ali to explain how unusual it is for most American Muslims to quote those who shaped or had been shaped by heterodox forms of Islam like the Nation of Islam or the World Community of Islam in the West.

This minor quibble aside, Women’s Mosque of America stands out as an important and skillful contribution to the study of gender, race, and religion. Ali’s meticulous analysis and ability to disentangle how individuals and communities grapple with their shared commitments to social justice and religious authority without homogenizing their experiences make her work a significant contribution to the study of Islam in America. I can’t wait to see how scholars and practitioners build upon Women’s Mosque of America in years to come.

Joseph Stuart is assistant professor of history at BYU. He is a scholar of African American history, particularly of the relationship between race, masculinity, civil rights, and religion in twentieth-century Black Freedom Movements. His forthcoming book manuscript examines the Nation of Islam’s racial and masculine ideologies to understand how and why some Black American groups opposed integration in the mid-twentieth century United States. The project traces the Nation of Islam’s founding from its origins in Great Depression Detroit to its schism following the Elijah Muhammad’s death in 1975 and its “restoration” under Louis Farrakhan. Joseph’s research has been published in academic journals and edited collections, including Church History: Studies in Christianity and Culture, American Quarterly, the Journal of Mormon History, and Religion & Politics. He is also a contributing research associate to the Century of Black Mormons Project. He has hosted and produced podcasts for the Neal A. Maxwell Institute for Religious Scholarship and the New Books Network.

Irum Shiekh

Tazeen Ali’s book, “The Women’s Mosque of America: Authority and Community in US Islam,” offers a comprehensive examination of the Women’s Mosque of America (WMA), which has been operational in the Los Angeles area since 2015. The book investigates the mosque’s role in providing a platform for American Muslim women to establish authority in Islamic knowledge and leadership. Drawing on Patricia Hill Collins’s Black feminist epistemology, which recognizes the expertise of Black women rooted in their lived experiences, Ali celebrates the Women’s Mosque for fostering sisterhood and solidarity among diverse Muslim women, particularly in matters of racial and social justice.[1] “The Women’s Mosque of America: Authority and Community in US Islam” contributes to the literature on American Islam and the experiences of Muslim women as they navigate Islamophobia and patriarchy to claim a theological space in the twenty-first century.

Since its establishment, the Women’s Mosque of America has garnered attention from scholars, journalists, and the public. While news reporters have documented its vision, challenges, and accomplishments,[2] academic scholars have contributed chapters to anthologies or examined the importance of an inclusive women’s space in books and journals.[3] However, Ali’s book is the first academic work to contextualize the mosque, engaging with its purposes, debates, and discourses. Through her research, Ali elevates the visibility and prominence of the Women’s Mosque of America. Moreover, the book invites elite academic circles to reconsider issues of religious authority, inspired by the activism of everyday women who apply their religious knowledge to carve out a space for themselves.

Ali’s research approach relies on ethnographic research, combining personal interviews with mosque members and attendees, textual analysis of online khutbas (sermons), and contemporary literature on women’s mosques and leadership. Employing participant observation and an interpretive anthropological approach, Ali seeks to understand women’s perspectives and motivations for establishing and sustaining the mosque. Recognizing her positionality as a research scholar and a Muslim woman, she situates herself in work to explore the importance of Muslim women attaining authority within their faith. Specifically, Ali highlights the everyday experiences and contributions of contemporary Muslim women activists and organizers, aligning with the mosque’s focus on lived experiences and the crucial roles of women in its development.

To situate her research within the framework of gender and religious studies, Ali heavily relies on scholarly texts authored and published by American Muslim women scholars. Figures such as Riffat Hassan, Asma Sayeed, Azizah al-Hibri, amina wadud, Asma Barlas, Kecia Ali, Sa’diyya Shaikh, Aysha Hidayatullah, Ayesha Chaudhry, Juliane Hammer, and others serve as the intellectual foundation for Ali’s work. By centering the work of these American Muslim female scholars, Ali challenges the prevailing belief that the essence of “real Muslims” or “true Islam” can only be discovered through male scholars interpreting medieval legal texts. Moreover, she emphasizes the significant strides made in Islamic authority by these scholars, addressing urgent issues such as gender inequality, anti-Blackness, and Islamophobia. The American context deeply influences their contributions, affirming Islam as a living faith within the United States. Ali effectively canonizes their work and establishes a tangible connection between their scholarship and the establishment of the Women’s Mosque of America.

Ali’s book documents and highlights the invaluable contributions of the Women’s Mosque of America, shedding light on its significant role in addressing the marginalization of women in mainstream mosques. While mainstream mosques have historically marginalized women’s participation and leadership due to patriarchal interpretations of Islam, the Women’s Mosque of America provides a platform for Muslim women, including those without formal Islamic education, to establish their authority rooted in the Quran. This inclusive space empowers women to assume leadership roles, including leading prayers and delivering khutbas, while interpreting the Quran in English.

In particular, Ali’s work addresses the void in the fields of Islamic and gender studies by focusing on the subject of Khutba as a platform for the development and dissemination of knowledge from women’s perspectives. Through ethnographic research and personal interviews, the book vividly illustrates how delivering the Friday sermon transforms khateebas (women who deliver Khutba) and empowers women in the audience. These khateebas are powerful role models, inspiring other women to refine their theological knowledge and reshape discourse on women’s issues locally and globally.

Despite the historical significance of the Friday khutba as a public oral sermon with extensive sociopolitical impact throughout Islamic history, scholarly research on this subject remains limited. The topic of Friday khutba has received scant attention in the realms of Arabic language, literature, and Islamic history.[4] Encyclopedias offer only a handful of entries, and contemporary literature has focused on male khatibs and the emergence of khutbas on platforms like YouTube.[5]

Ali’s work fills this critical gap in scholarly research on the khutba. By delving into the experiences of female khateebas and conducting meticulous textual analysis, Ali provides fresh insights into this underexplored area. The book demonstrates the distinct value of khutbas in providing human perspectives on religious and sociopolitical texts and highlights its potential for fostering Islamic knowledge. Furthermore, Ali presents compelling case studies of Muslim women delivering khutbas, challenging long-standing assumptions and debates surrounding women’s involvement in this practice.

The absence of women delivering khutbas has resulted in several areas of inquiry that require exploration from women’s perspectives. The book emphasizes that the Women’s Mosque of America provides opportunities for women to participate in theological leadership positions and develop their skills in delivering impactful sermons through mentorship and training. It also highlights the wide range of issues addressed in these khutbas, particularly those significant for women of color, an aspect often overlooked in mainstream mosques. By delivering khutbas in English and adhering to the Women’s Mosque of America guidelines, everyday women engage with the Quran and nurture a stronger connection with God. Ali invites readers to explore uncharted areas of inquiry within both classical and contemporary scholarship.

The book opens with Gail Kennard’s impactful khutba delivered in 2015, where she explores the role of Prophet Muhammad’s multiple wives as devoted disciples actively involved in safeguarding and spreading Islam. As a convert to Islam, Kennard turned to the Quran for answers and discovered that the Prophet’s wives were specifically designated as “mothers of the believers,” distinguishing them from other women. Through thoughtful research and applying that knowledge to her life, Kennard skillfully established connections between these Quranic verses, the Prophet’s wives, and the twelve disciples of Jesus. Her insights expanded the roles of Muhammad’s wives beyond domesticity, challenging the prevailing narrative that limits their contributions to household caretaking. Kennard’s khutba exemplifies the khateeba’s ability to bridge Quranic teachings and the life of Prophet Muhammad with contemporary issues, emphasizing the practical relevance of Islamic values in the twenty-first century. Her contribution sheds new light on the significance of Prophet Muhammad’s wives and encourages reevaluating women’s roles in Islamic and contemporary contexts.

In the book’s conclusion, Ali returns to Gail Kennard’s khutba, highlighting its compelling message directed towards Muslim men. Kennard expresses gratitude for the support received from several brothers who approached her after hearing about the speech, expressing willingness to attend or listen to the audio recording. She emphasizes the crucial significance of Muslim men actively engaging with and attentively listening to the voices of Muslim women, expressing hope for a future where these voices are truly heard.

While acknowledging and appreciating the support of contemporary Muslim men who actively encourage the establishment of spaces for women to exercise religious authority, further exploration is warranted. Personal interviews with male religious community board members in Southern California could provide valuable insights. Such interviews would shed light on the transformative impact of the women’s mosque on the roles and status of women within religious institutions. Additionally, investigating the women’s mosque’s influence on other mosques’ prayer practices would offer enlightening perspectives. How are these spaces creating more opportunities for women within traditional mosques? How is the leadership landscape changing, particularly within mosque boards and other positions of authority? This research would contribute to a better understanding the broader impact of the Women’s Mosque of America within Muslim communities.

Just as the Women’s Mosque of America has played a vital role in reshaping the landscape of Muslim women’s roles in contemporary theological spaces, Ali’s book significantly contributes to institutionalizing women’s perspectives within the mainstream religious studies discipline. By focusing on American Muslim female scholars and amplifying their voices, the book actively challenges the dominance of canonized knowledge perpetuated by male scholars. With a gendered analysis that explores female bodies engaging with social justice issues, the author employs a bottom-up approach to reshape the discourse surrounding religious authority within academic disciplines.

[1] Patricia Hill Collins, Black Feminist Thought: Knowledge, Consciousness, and the Politics of Empowerment (New York: Routledge, 1991).

[2] Antonia Blumberg, “Women’s Mosque Opens in LA with a Vision for the Future of Muslim-American Leadership,” Huffington Post, January 30, 2015, www.huffpost. com; Tamara Audi, “Feeling Unwelcome at Mosques, 2 Women Start Their Own in LA,” Wall Street Journal, January 30, 2015, www.wsj.com.

[3] Irum Shiekh, “Women’s Mosques: Spaces to Rethink about Gender and Religious Authority,” in Oxford Handbook of Religious Space and Place, ed. Ambros Barbara David Bains Susan Lochrie Graham Leonard Norman Primiano and David Simonowitz (New York: Oxford University Press, 2022); Simonetta Calderini, Women as Imams: Classical Islamic Sources and Modern Debates on Leading Prayer (London: I.B. Tauris, 2020);

[4] Tahera Qutbuddin. . “Khutba: The Evolution of Early Arabic Oration,” in Heinrichs, Wolfhart, and Michael Cooperson. Classical Arabic Humanities in Their Own Terms: Festschrift for Wolfhart Heinrichs on His 65th Birthday. Boston: Brill, 2008, 176-273; Linda Jones, The Power of Oratory in the Medieval Muslim World. (Cambridge UP, 2012).

[5] Charles Hirschkind, “Experiments in Devotion Online: The YouTube Khutba.” International Journal of Middle East Studies, vol. 44, no.1 (2012): 5-21.

Dr. Irum Shiekh is a visual artist and oral historian who has been producing scholarship that highlights the contributions of marginalized communities in reshaping master narratives. Her book, Detained Without Cause: Muslims, provides oral histories of Muslims who were wrongfully detained and deported in connection with the September 11 attacks. Her documentary, Matrilineal Muslim Women of Minang, provides narratives of Muslim women of Minangkabau, the largest living matrilineal society in the world, which happens to be Muslim. By presenting interviews of strong Muslim women wearing headscarves, this film also disassociates the largely mistaken image of women’s oppression with Islam. Dr. Shiekh was a Fulbright scholar in Palestine where she developed courses about Palestinian Cinema and its significance in writing a counter-narrative through artistic expressions that articulates multiple histories and the day-to-day perspectives of Palestinians. Her photo exhibit, Palestinians Envision Life Without Occupation, examines the power of imagination as a resistance strategy for Palestinians living under occupation. Her latest publication for Oxford University Press, titled “Women’s Mosque: Places to Rethink Gender and Religious Authority,” combines historical research and ethnographic fieldwork to examine the rituals of Friday prayer at the Women’s Mosque of America based in Los Angeles. Her research reveals that through engaged discussions and practices, mosque-going women are widening the circles of female scholars in local communities, making the mosque instrumental in developing and disseminating Islamic knowledge that deconstructs patriarchal interpretations of the Qur’an and empowers women. She currently teaches part-time in the Department of Ethnic Studies at UC Riverside. Her future goals include writing and directing a fictional film or television series.

Tazeen Ali

What a privilege it is to have such close engagement with The Women’s Mosque of America: Authority & Community in US Islam by the six brilliant scholars of this forum. The generative insights they have yielded from their respective areas of expertise in Islamic Studies, Sociology, and American religion, provide new ways to consider the claims in the book. Their essays also offer a path forward in research at the intersections of Islam, gender, and race in the US.

American Muslim Women’s Authority, Islamophobia, and US Politics

As I argue in the book, the Women’s Mosque of America emerges from feminist exegesis of the Qur’an. Here, amina wadud’s scholarship and activism operate as an analytical framing device throughout the book to understand the history of the WMA and its place in US Islam. Given this fact, I am humbled by her attentive and thorough reflections on the book. While there is much to unpack, wadud’s comments prompt me to reflect further on the role of Islamic feminist frameworks in the US alongside Islamophobia and anti-Muslim racism, as they inform the emergence of Muslim women’s religious authority.

In her generous remarks, Inaash Islam describes the book as an illustration of “the empirical potentials of Islamic feminism in the United States.” As wadud reminds us in her review, these potentials are always shaped, and maybe even limited, by Islamophobia, which informs the gendered dynamics of American Muslim communities. wadud traces the rise of Muslim women’s religious authority in tandem with the rise of what she names patriarchal conservatism, positing that Islamophobia may be “one reason why confessional Islam in America is so peculiarly conservative, patriarchal, hegemonic and binary.”

Esra Tunc also alludes to the patriarchal conservatism of Islam in America. Tunc keenly situates the book in conversation with recent developments in American Muslim communities whereby several mainstream Muslim religious leaders have aligned themselves with right-wing political discourses on LGBTQ+ issues. This is despite the explicit Islamophobia of the supporters of these discourses. Tunc’s juxtaposition of Muslim leaders who profess politically conservative views on gender and sexual difference, with the WMA’s approach to Islamic legal debates and scriptural interpretations is thought-provoking. It suggests to me that the model of Islamic authority promoted at the WMA, one that is rooted in Muslims’ bodily experiences, could lead American Muslims to alternative political alliances within the already fraught landscape of gender politics in the US.

Moreover, it is curious to consider alliances between American Muslims and the US political right, especially considering the gendered dynamics of Islamophobia and anti-Muslim racism. As Islam writes, as Muslim women navigate “racialized sexism and gendered racism in the US” they are faced with the double bind of trying to critique patriarchal Islamic discourses “without giving ammunition to Islamophobes in the current climate.” Yet not all American Muslims seem concerned with anti-Muslim racism in the US political sphere when they align themselves with political platforms that are explicitly discriminatory against Muslims. Such alliances are disproportionately harmful to the most vulnerable Muslims and risk alienating them from Islam altogether, bringing into sharper relief the question that wadud poses: “how does one find a place within [Islam] if one is not a cis-gendered heterosexual man?” The model of Islamic authority at the WMA, particularly in its reliance on embodied experiences and vulnerability, as each of the reviewers in the forum highlight so well, provides one possible answer. As wadud reminds us, “all interpretations are rendered from the lived realities of the interpreters” but men’s experiences are assumed to be universal. Islamic feminism as the framework of communities like the WMA, then, can help to challenge hegemonic models of Islamic authority in the US that take for granted the universality of the male experience.

Furthermore, Iman AbdoulKarim and Irum Shiekh draw our attention to parallel patterns of hegemonic authority that privilege men and Arabic expertise within the academic study of Islam. In her analysis, AbdoulKarim places the book in opposition to scholars and leaders “who hold onto mono-dimensional representations of Islam and out-of-touch renderings of U.S. Muslim concerns to police the boundaries of what it means to be Muslim, study Islam, and name U.S. Muslims’ relationship to contemporary U.S. politics.” Shiekh goes even further to suggest that in the book’s reliance on scholarship by American Muslim women scholars, it “effectively canonizes their work and establishes a tangible connection between their scholarship and the establishment of the Women’s Mosque of America.” Moreover, she writes that the book functions to institutionalize women’s scholarship within the discipline of Islamic Studies. This is an angle I had not previously considered so explicitly, and I am appreciative of this framing. Shiekh’s and AbdoulKarim’s assessments prompt us to deepen routine reflections about scholarly positionality and think more meaningfully about how scholars both reproduce and resist gendered and racialized hierarchies in their engagements of these same topics.

Islam, (Anti)Blackness, and Intra-Muslim Inclusivity

In AbdoulKarim’s incisive remarks on how Islam and Blackness manifest at the WMA, she identifies the significance of naming the influence of Black feminist thought and religious history. For her, this naming accomplishes two goals. First, it situates the WMA within an African American genealogy, contextualizing it as the “continuation of the blurring between the religious and political that has characterized U.S. Black women’s history.” Second, she continues, this naming can facilitate tracing how (Black) American Islam influences the global trends in Islamic authority, even when not acknowledged as such. AbdoulKarim’s lucid framing beautifully illustrates one of the core presuppositions of my book: that American Muslim history is African American History. Therefore, if we are to take seriously developments in American Islam as pertinent to Islamic trends around the world, then we can indeed, as AbdoulKarim invites us to do, “consider how race, Black thought, and African American religious history influence religious authority in contemporary U.S. Muslim communities and shape, whether named or not, its influence on global debates about Islamic religious authority.”