At 34°, it is one of the hottest days of the year in Istanbul. And while many Istanbullus might be tempted to stay at home or retreat to a cafe with good A/C, I have more important things on my mind: I have managed to secure a meeting with one of the foremost collectors of objects and ephemera related to the hajj in the Republican era of Turkey. Fatih Ketancı, who is a documentary producer by trade, has been collecting these items for the last six years, scouring the flea markets and antique bazaars of Ankara, Istanbul and his home-city of Bursa.

Fatih Ketancı, who is a documentary producer by trade, has been collecting these items for the last six years, scouring the flea markets and antique bazaars of Ankara, Istanbul and his home-city of Bursa.

As I enter his house – in a somewhat disoriented fashion thanks to the elements – he greets me with a fresh glass of orange juice, gratefully accepted; this is not the time to play the shy guest. We sit down in his living room and recall our first meeting a few months earlier thanks to a mutual friend. On that occasion, I realised that Fatih Bey was behind hachatirasi, an account on Twitter that I had been following for some time. As we chat, I have half an eye on the large dining table to the left of the room, which Fatih Bey has taken the liberty of loading with various files, folders, and objects. Ordinarily, that would make me an impolite guest, yet it seems that he is as eager as me to dive into his collection. Over the next eight hours, with an occasional break for some of Kadıköy’s best börek, sarma, and kazandibi (and of course, the mandatory çay), we sift through his collection.

In truth, I had expected to spend three or four hours with Fatih Bey, yet our shared passion for the hajj and everyday (or ”folk”) religion sustains the conversation. I wrote a PhD dissertation on the history of the hajj in the Ottoman Empire between the sixteenth and eighteenth centuries, with an entire chapter on some of the objects and illustrations at the heart of hajj culture in that time. I was always interested in how this culture developed following the dawn of the Turkish Republic, especially considering the many religious and cultural ruptures that it occasioned.

Collecting the hajj

Considering Fatih Bey’s own passion for the subject, it is surprising to hear that he initially began accumulating these items without intending to establish a fully-fledged collection. He noticed that the tezgahs of flea markets were awash with items featuring sacred content – verses from the Quran, illustrations of the Kaʿba and the Prophet’s Mosque, and hajj mementos – and felt an obligation to give them a better home. This sparked his interest in the more human elements behind these items, which in turn has sustained his collecting practices for the past six years. In fact, in its richness and vastness, his collection gives the appearance of someone who has been collecting for much longer.

“The real value of his collection does not lie in its monetary worth; Fatih Bey is interested in stories. Vendors can be indifferent to the same postcards, leaflets, and photographs with which he is so fascinated, yet he sees the personalities behind the objects.“

The real value of his collection does not lie in its monetary worth; Fatih Bey is interested in stories. Vendors can be indifferent to the same postcards, leaflets, and photographs with which he is so fascinated, yet he sees the personalities behind the objects. On other occasions, Fatih Bey is gifted objects precisely because those offering the items, usually family members who have inherited them, recognise his appreciation for their sentimental value. He also has agents and vendors contacting him with items of interest from time to time. As a result, he has amassed one of the most comprehensive archives of hajj practice in Turkey over the past century.

Fatih Bey’s personal connection to the subject can be discerned from a separate set of objects and artefacts that take pride of place in a section of his living room (fig. 2). These include a Zamzam bottle made of Chinese blue-and-white porcelain, most likely dating to the nineteenth century. Like many similar examples in the collection of the Topkapı Palace, Fatih Bey’s own bottle retains its leather and wax seal, even though it is empty. There is a smaller, metal vessel of Zamzam, which he tells me was meant to be opened upon the death of its original owner and carefully dripped into their mouth as they underwent the ritual bathing.

He points out that this association with death is a common thread with several artefacts from Mecca and Medina. For example, pilgrims would collect soil from the tombs of the Prophet Muhammad’s family in the Baqi graveyard in Medina, with the intention that the soil be sprinkled on their own tomb when they passed away. One of these pouches, roughly a century old, is in Fatih Bey’s collection. Only the scuffed inscription on its front betrays its original function, since unlike the small container of Zamzam, its contents did end up serving their intended purpose. Yet the fact that it once contained this sacred soil is enough to make even this empty bag a repository of sacred blessings, or baraka. Fatih Bey’s collection includes another rare and precious item, a scoop of gravel from the courtyard of the Kaʿba which has since been entirely paved in marble.

Routes to Mecca

The pilgrimage to Mecca was one of the casualties of the secularising policies of the young Turkish Republic following its establishment in 1923, which explains why the earliest item in Fatih Bey’s (main) collection dates to 1947. Along with the abolition of medreses and Sufi orders, the replacement of Arabic with Turkish as the language of the call to prayer, and the banning of religious clothing, the ruling Republican People’s Party (Cumhuriyet Halk Partisi; CHP) placed various obstacles in the path of those wanting to undertake the hajj. Turkey’s transition to a multi-party democratic system in 1946, along with the pressure this placed on the CHP’s approach to religious matters, resulted in Turks once again being permitted to undertake the hajj a year later. Yet in 1948, the CHP rowed back on this decision, citing a lack of foreign currency. It was only after pressure from the opposition and calculations around the looming elections that in 1949 the hajj was once again authorised for Turkish pilgrims. This remained the case following the victory of the Democratic Party (Demokrat Parti) in the 1950 elections.[1]

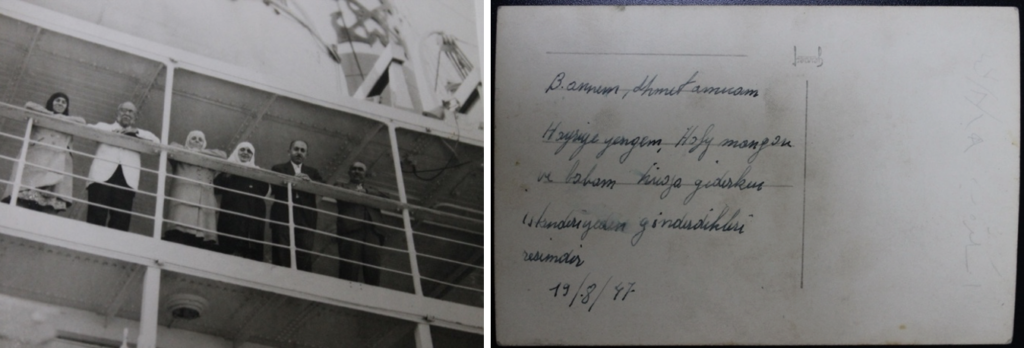

Fatih Bey says that according to some estimates, 7000 pilgrims undertook the hajj from Turkey in 1947. One of his most prized possessions is a photograph of six pilgrims from that group, waving happily from their ship at the Mediterranean port city of Alexandria (İskenderiye) (figs. 3 and 4). The sea route was by far the most safe and inexpensive option in these early years. Pilgrims would eventually make their way to Jeddah through the Suez Canal, with the journey taking a total of ten days in total.

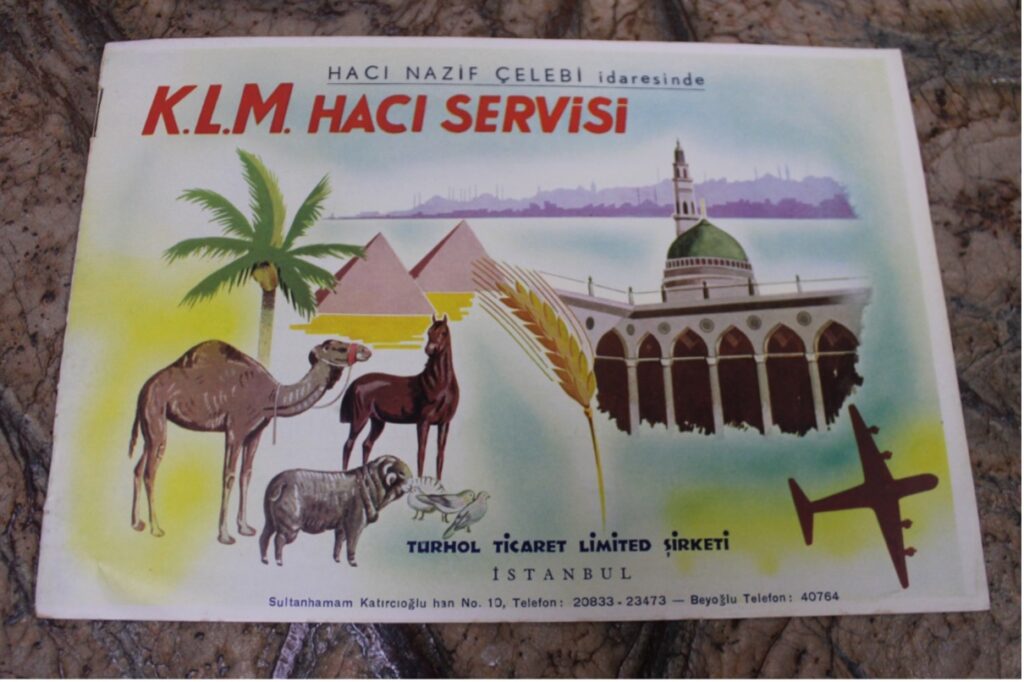

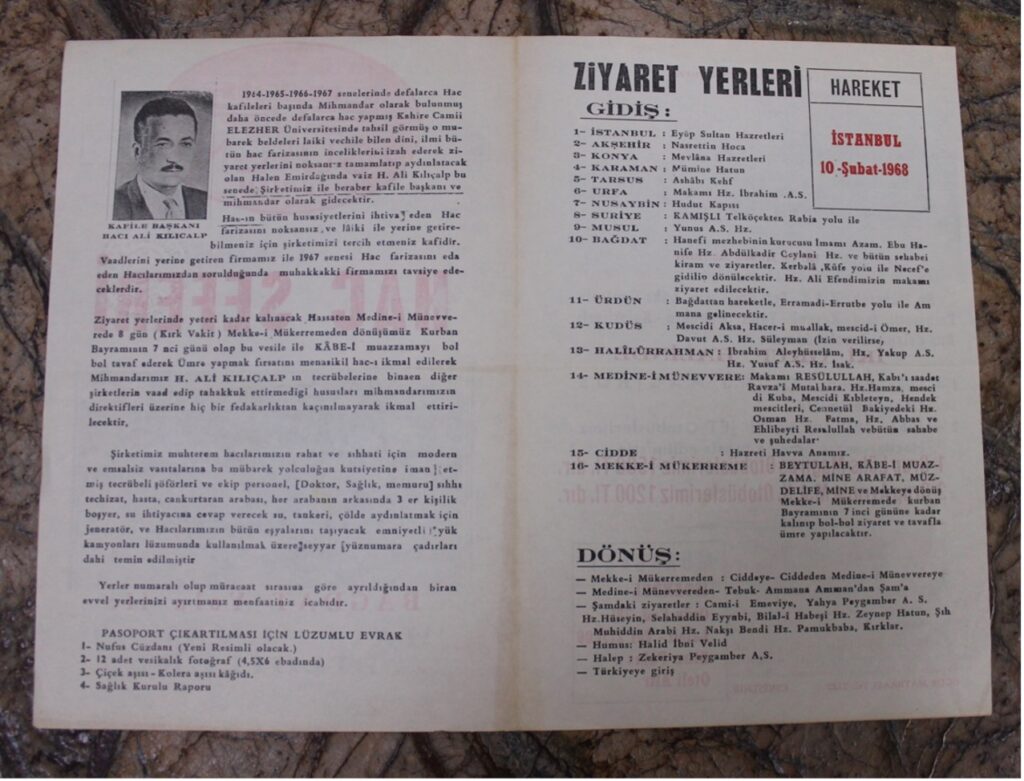

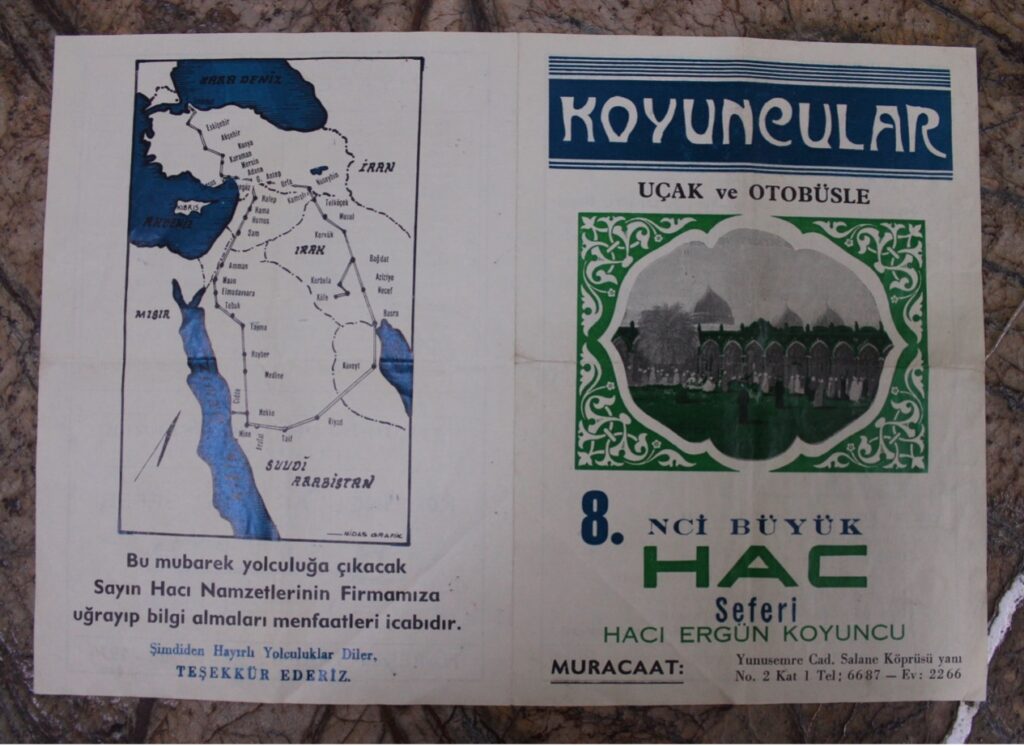

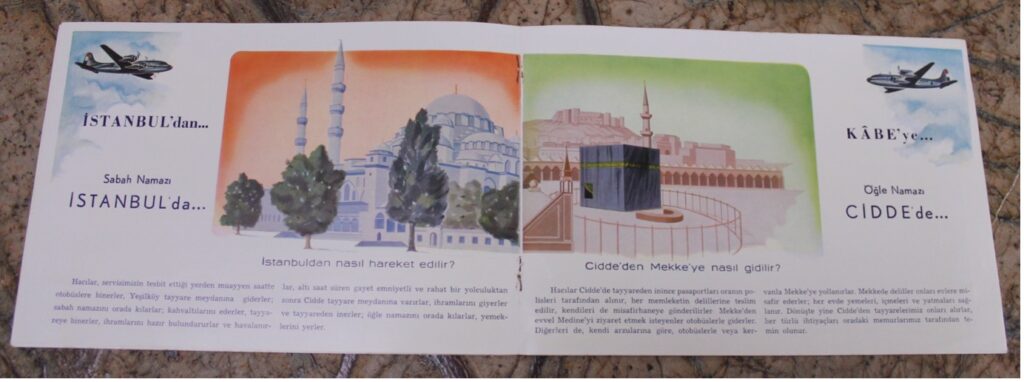

Air travel was also an option, though undoubtably more expensive. According to a brochure issued by Koyuncular Hac Seferi in 1974, an air ticket via Turkish Airlines cost almost four times the price of a coach ticket (7,500 versus 2,000 Turkish Lira) (figs. 10 and 11). One of Fatih Bey’s favourite items is a brochure produced by Hacı Nazif Çelebi in 1950, who offered the first air package to the hajj with KLM Royal Dutch Airlines (figs. 5 and 6). Hacı Nazif was also one of the first figures in Turkey to found a hajj agency following the easing of restrictions on Turkish pilgrims. Similar hajj agencies continued to serve Turkish pilgrims until 1979, when the Directorate of Religious Affairs (Diyanet İşleri Başkanlığı) was handed full control over management of the hajj. Fatih Bey admires Hacı Nazif for his careful planning, not only of his travel package but also of his brochure! Its production value certainly does stand out, with vibrant colours printed on high-quality, silky paper. Its tagline also catches the eye, offering pilgrims the unprecedented possibility of praying the dawn prayer in Istanbul and the afternoon prayer in Jeddah (‘Sabah namazı İstanbul’da, Öğle namazı Cidde’de’).

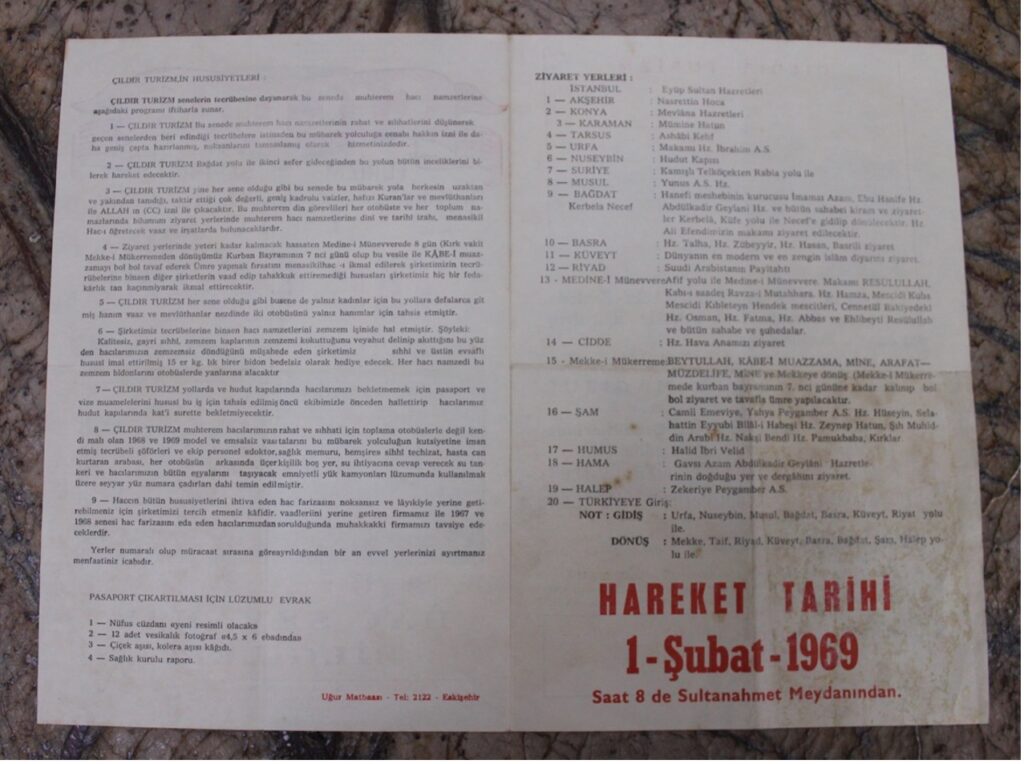

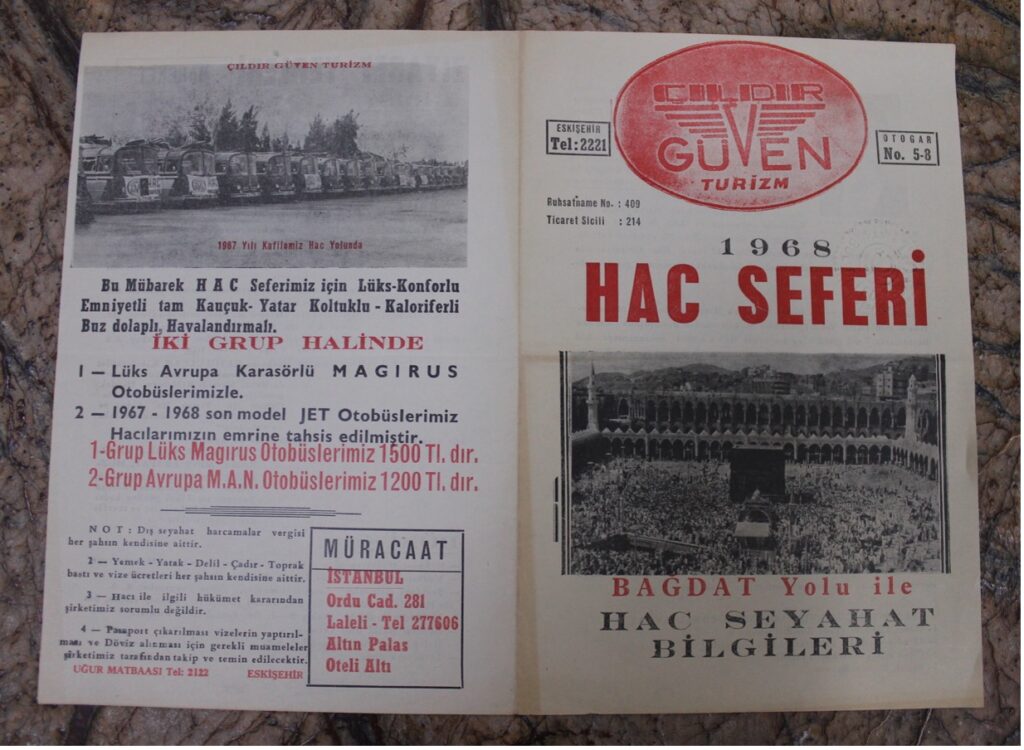

“A flyer from 1964 advertises the hajj via Syria and Palestine, though a more popular choice went via Baghdad (‘Bağdat yolu’). Pilgrims opting for this latter choice visited Baghdad, Kufa, Karbala, as well as Jerusalem (Kudüs) and Hebron (Halîlürrahman), taking in the sacred sites of Damascus on the return journey.“If Fatih Bey’s collection of brochures is anything to go by, the land route to Mecca was by far the most popular in the 1960s and 1970s. A flyer from 1964 advertises the hajj via Syria and Palestine, though a more popular choice went via Baghdad (‘Bağdat yolu’) (figs. 7 and 8). Pilgrims opting for this latter choice visited Baghdad, Kufa, Karbala, as well as Jerusalem (Kudüs) and Hebron (Halîlürrahman), taking in the sacred sites of Damascus on the return journey. This road had been less secure in the late 1940s and 1950s due to instability in the region, especially following the first Arab–Israeli War in 1948. Moreover, the old Hejaz railway route had remained in a state of disrepair following its destruction during World War I. Following the six-day war of 1967, Jerusalem once again ceased to be an option for Turkish pilgrims, showing how political realities could impact everyday hajj practice.

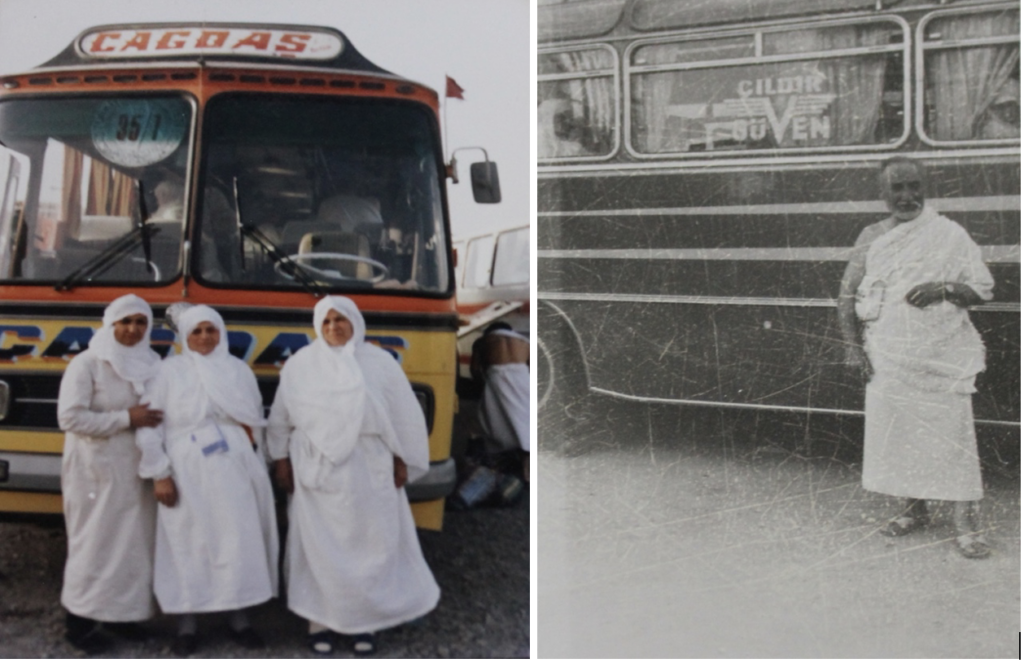

Lüks-konforlu-emniyetli

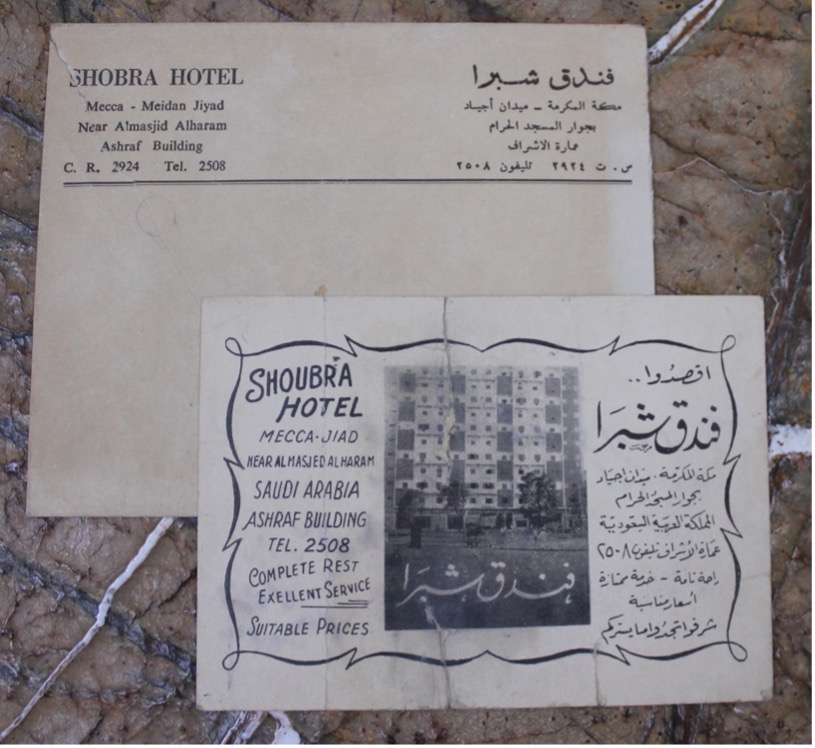

As Fatih Bey’s rich collection of flyers and brochures shows, agents emphasised that their packages were first-rate, comfortable, and safe (lüks-konforlu-emniyetli) (fig. 9). This was especially important since pilgrims would spend several days on the road, with a significant amount of the journey occurring across desert terrain. Pilgrims travelling with Koyuncular Hac Seferi in 1974 departed Istanbul on 26 November (12 Zilkade 1394), leaving them 25 days to reach Mecca in time for the first day of the hajj (22 December/ 8 Zilhicce) (figs. 10 and 11). For an all-inclusive price tag of 2000 Turkish Liras, pilgrims could secure a ticket aboard Koyuncular’s Mercedes coach featuring a range of modern amenities, from reclining seats and fridges to heating and air conditioning. They also benefited from the provision of religious and medical teams, water tankers, luggage trailers, and lighting devices for use on the desert road. All of this would have endowed Turkish pilgrims with an invaluable sense of security ahead of the long trip to Mecca.

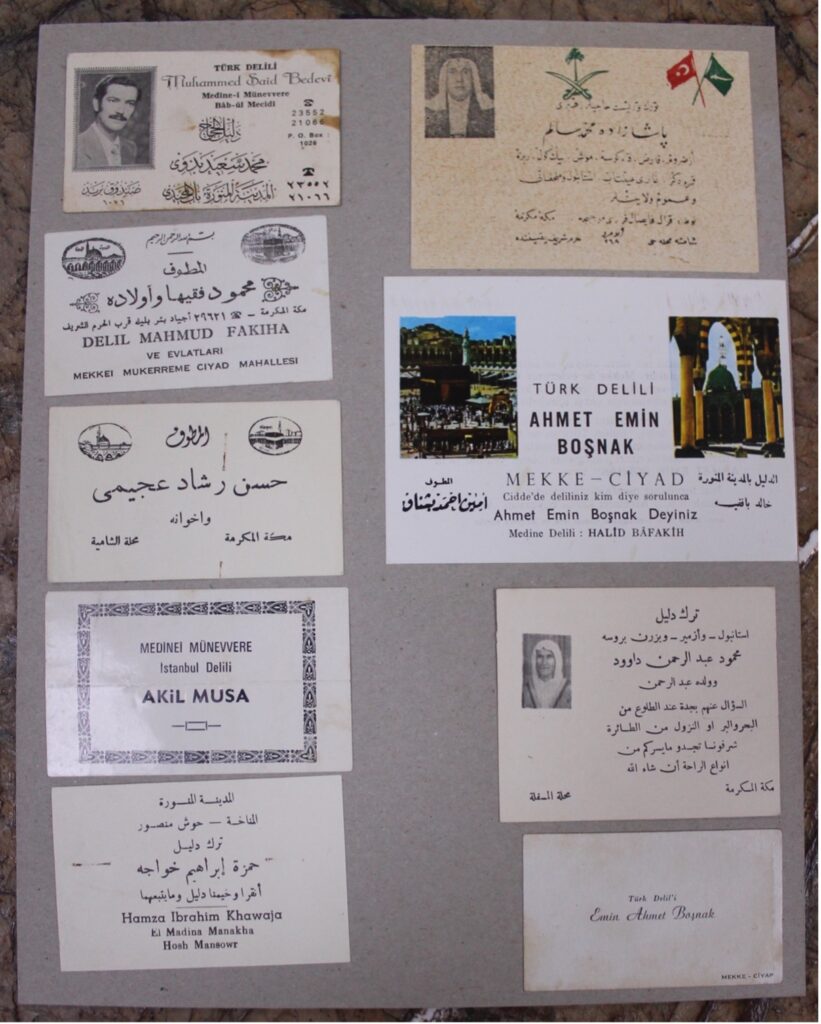

While the brochures frequently promise the presence of religious officials on their tours, Fatih Bey’s collection of business cards belonging to local guides (delils) suggest that these experts were just as important once the pilgrims had reached Mecca (fig. 12). Some guides were themselves Turks who had settled in the Holy City. As well as helping pilgrims to complete their rituals, they were probably more resourceful than tour operators when it came to navigating day-to-day practical challenges within Mecca (and Medina). Fatih Bey’s collection of business cards suggests that guides could sometimes serve pilgrims from specific cities in Turkey, as in the case of Akil Musa, who attended Istanbul pilgrims in Medina. Other guides served pilgrims from Bursa, Izmir, and Ankara.

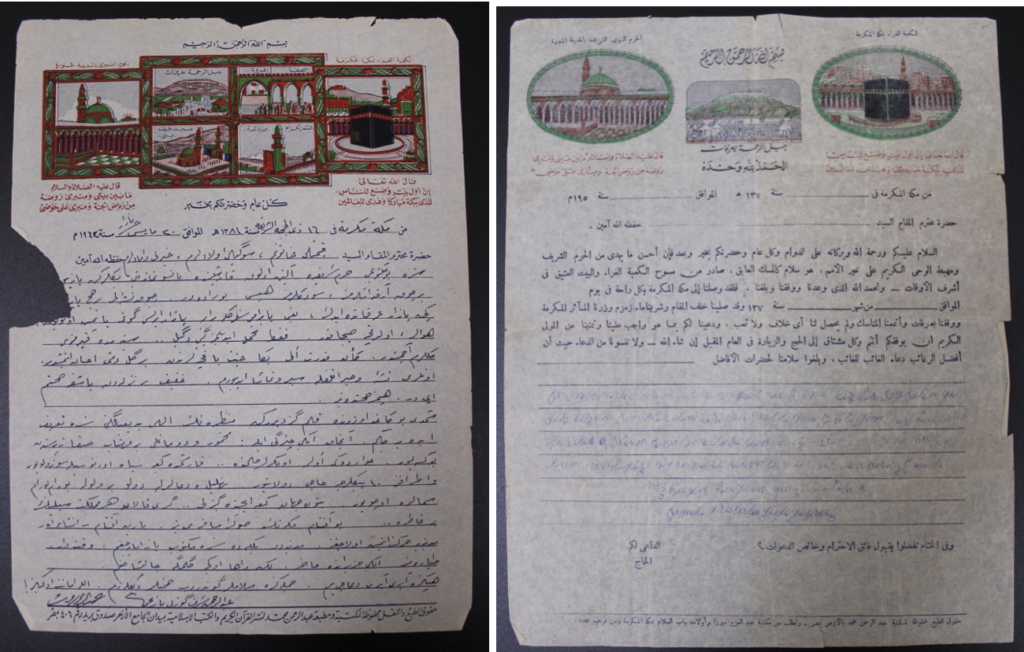

Once safe and sound within Mecca, pilgrims would write home, usually on paper featuring illustrations of the Kaʿba and the tomb of the Prophet Muhammad. Along with their undoubted sentimental value, these letters were preserved due to these sacred depictions, explaining why so many of them have survived long enough to enter Fatih Bey’s collection. One of the earliest such pieces dates to 1381 AH (corresponding to 1962), and features sacred sites of the hajj, including Safa-Marwa, Arafat, Mina, and Muzdalifa, alongside the Kaʿba and the Prophet’s tomb (fig. 13). Another letter features a typed message below the illustrated letterhead with blanks allowing the pilgrim to fill in their date of arrival for the intended recipient (fig. 14). The message also saves pilgrims the trouble of mentioning that they had successfully completed their initial rituals at the Kaʿba and drunk from the Well of Zamzam.

.

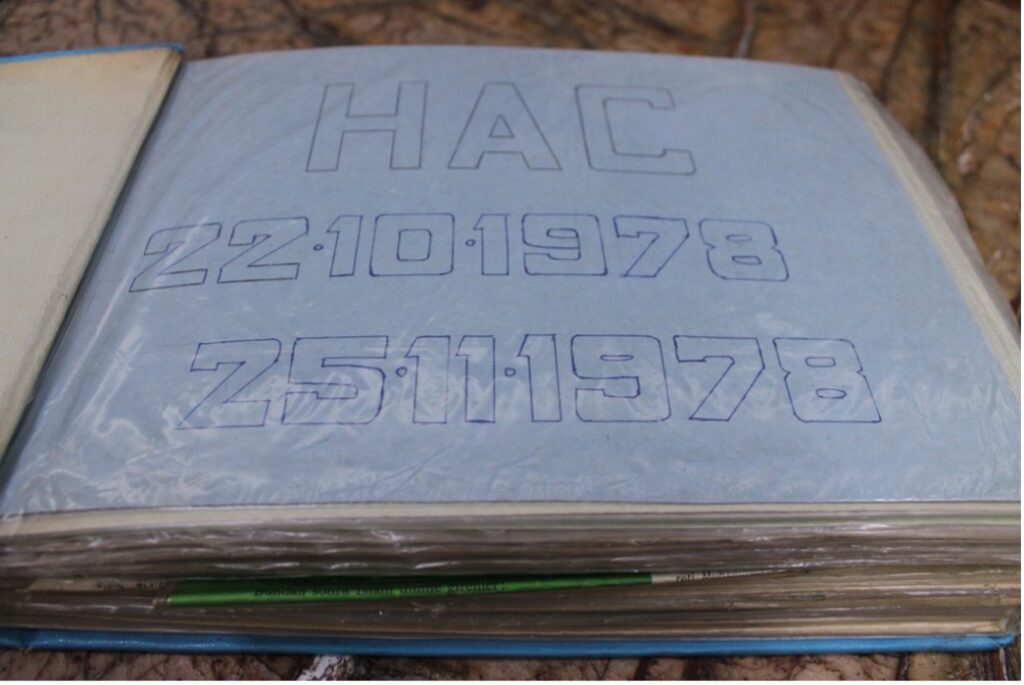

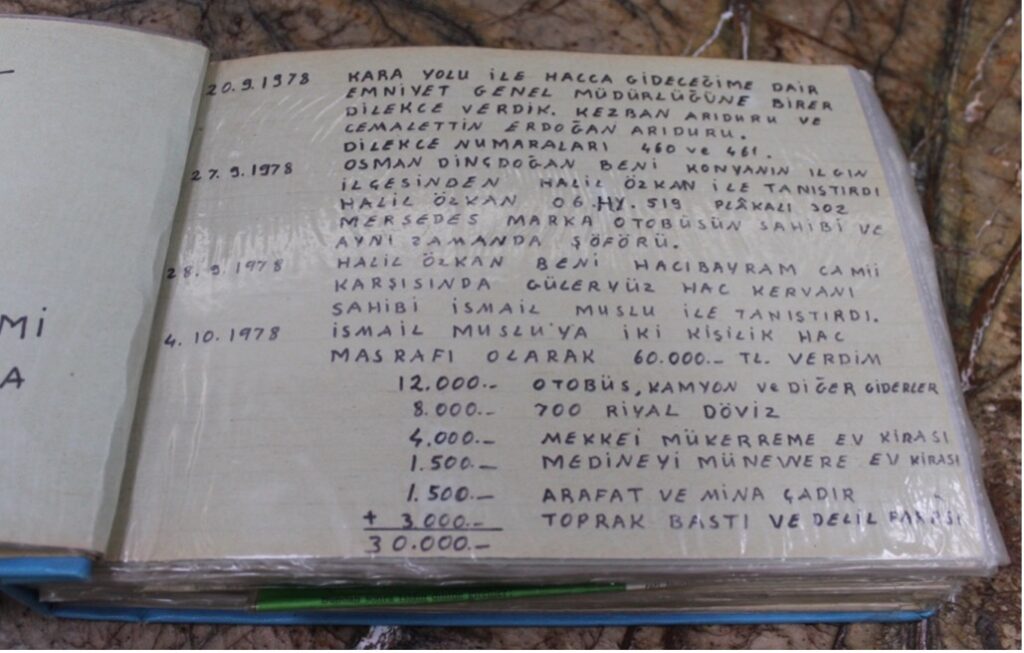

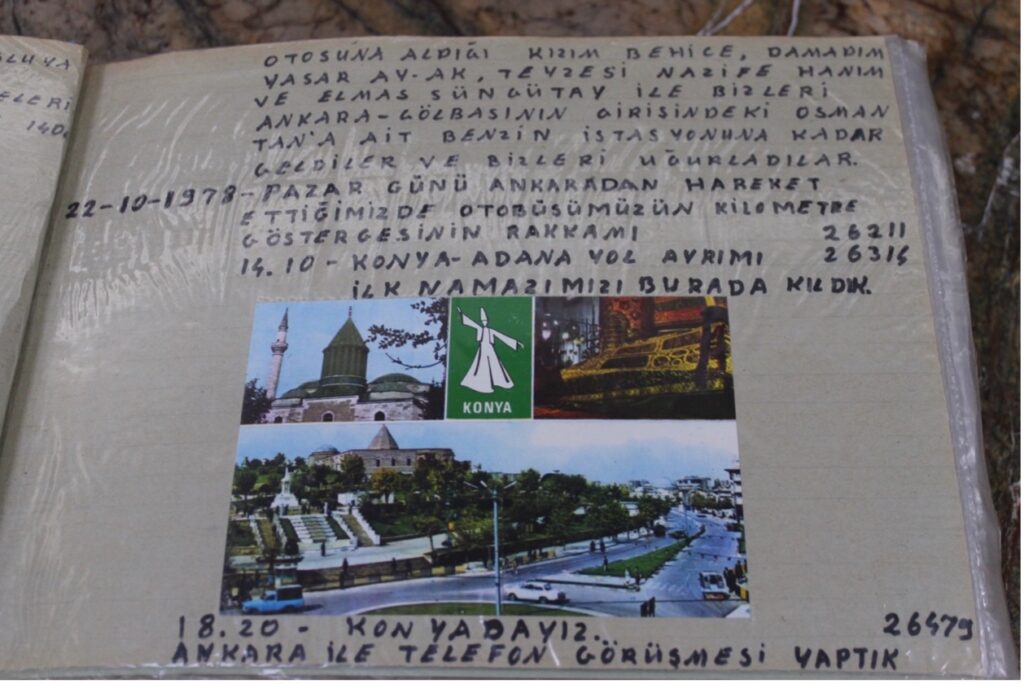

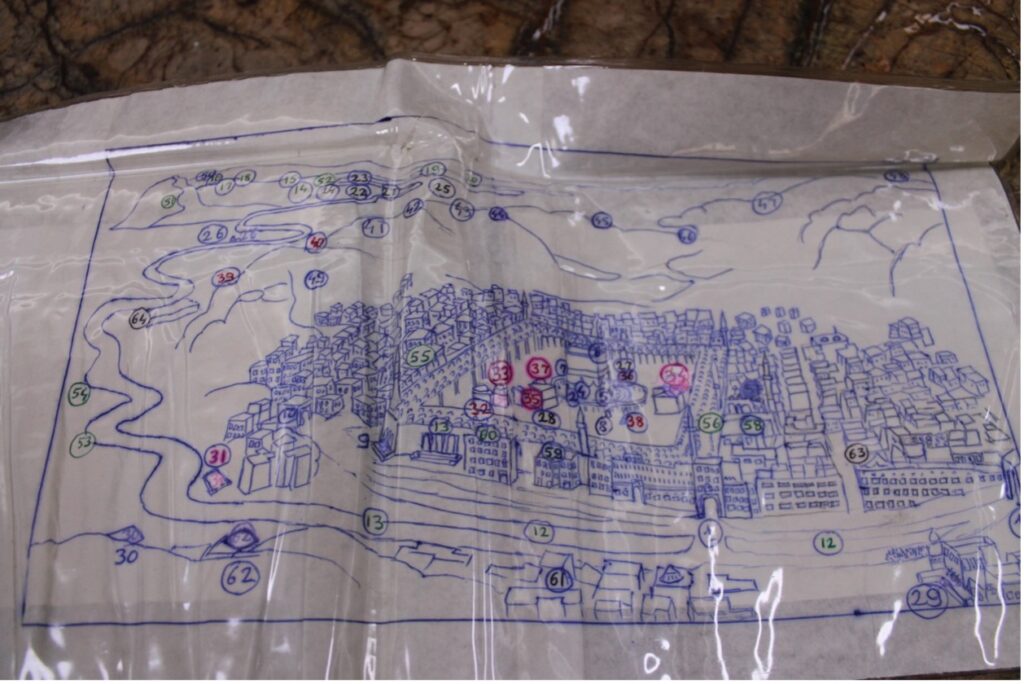

Some pilgrims devoted even more time to putting pen to paper, as in the remarkable case of a Turkish pilgrim by the name of Erdoğan Arıduru. Erdoğan Bey undertook the hajj by road in 1978 and kept a diary of each day of his journey. His notes are exhaustive and reflect his fascination for the more modern aspects of the hajj, including the kinds of vehicles and machinery in use at the cities on the long road to Mecca. He notes not only the coach that he travelled on (a Mercedes 302 model) but also its license plate (06 HY 519) (fig. 17). He and his wife were allocated seats behind the driver, allowing him to note how many kilometres had been travelled from one location to the next in the right-hand column of his travelogue (fig. 18). Erdoğan Bey was a collector in his own right, as can be seen from the postcards and other ephemera from every place he visited. His interest in the sacred sites was just as methodical; one of the most remarkable features of his travelogue is his map of the Sacred Mosque of Mecca and its surroundings (fig. 19).

Keepsakes from the Holy Land

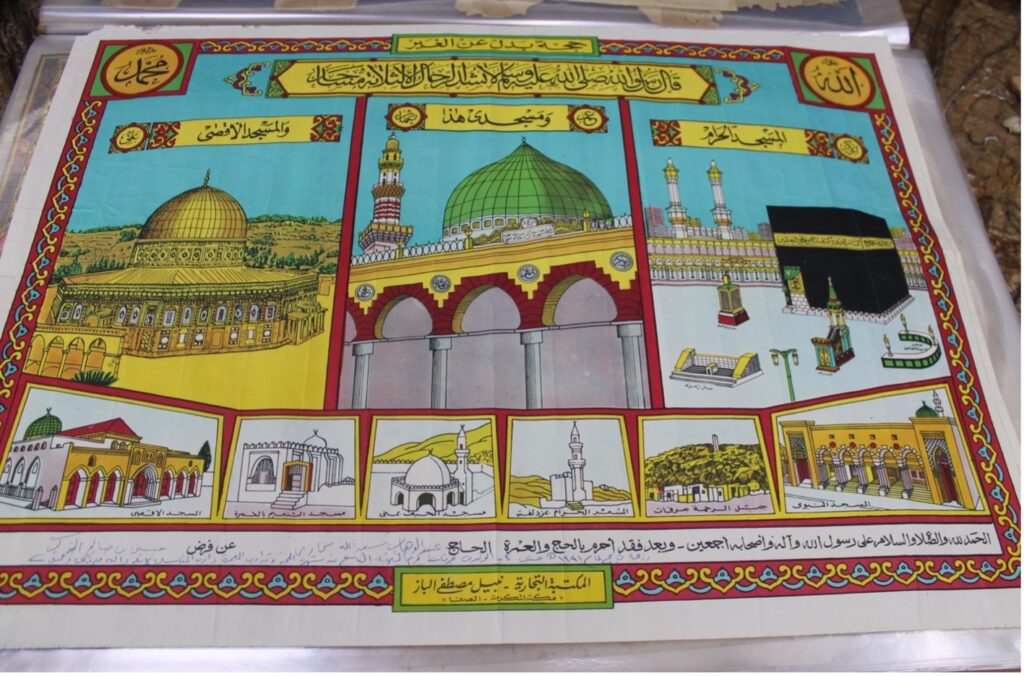

Whether undertaking the hajj for themselves or as a proxy (bedel) for a chronically ill or deceased person, pilgrims frequently returned home with certificates verifying that they had completed the rituals. There are many different examples of these in Fatih Bey’s collection, though most feature similar depictions of different sacred sites in Mecca and Medina and occasionally Jerusalem (fig. 19). Intended for display, the certificates provided a lasting memory of the hajj for pilgrims and put their newly-gained status as a hacı in writing.

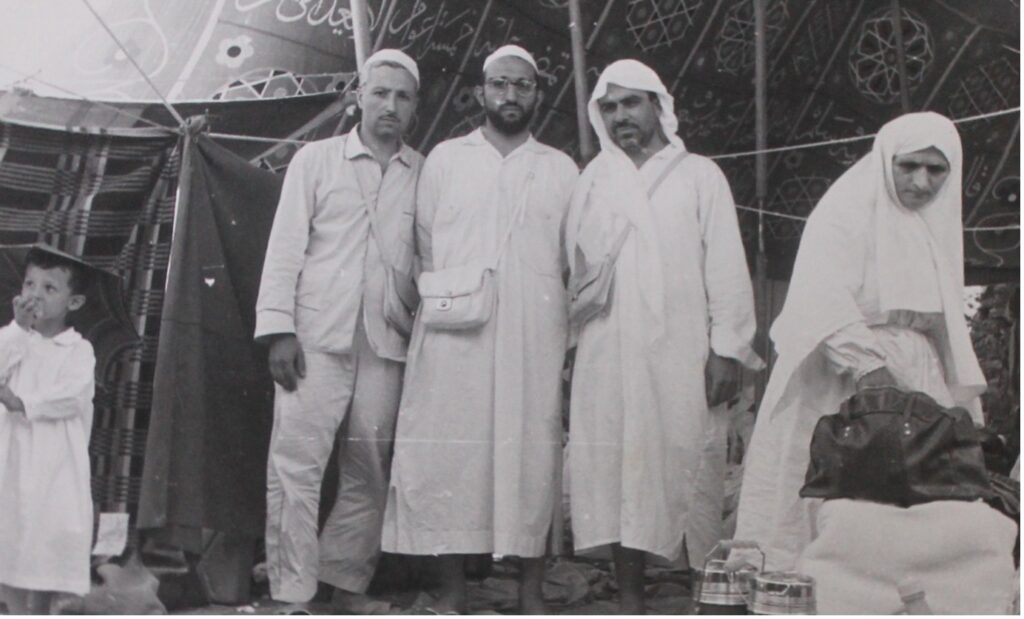

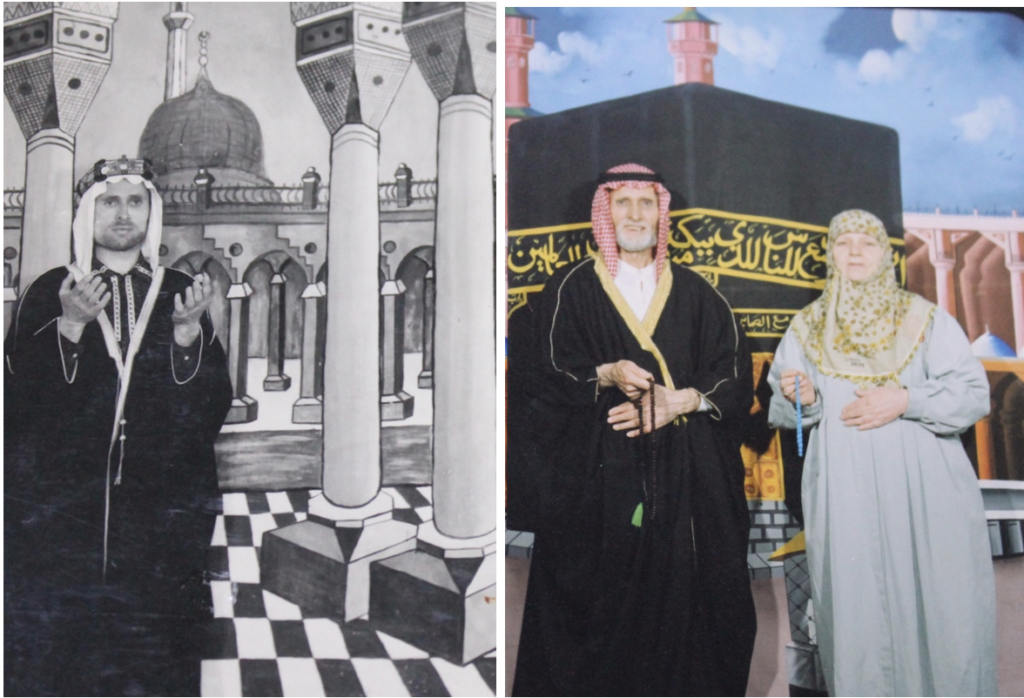

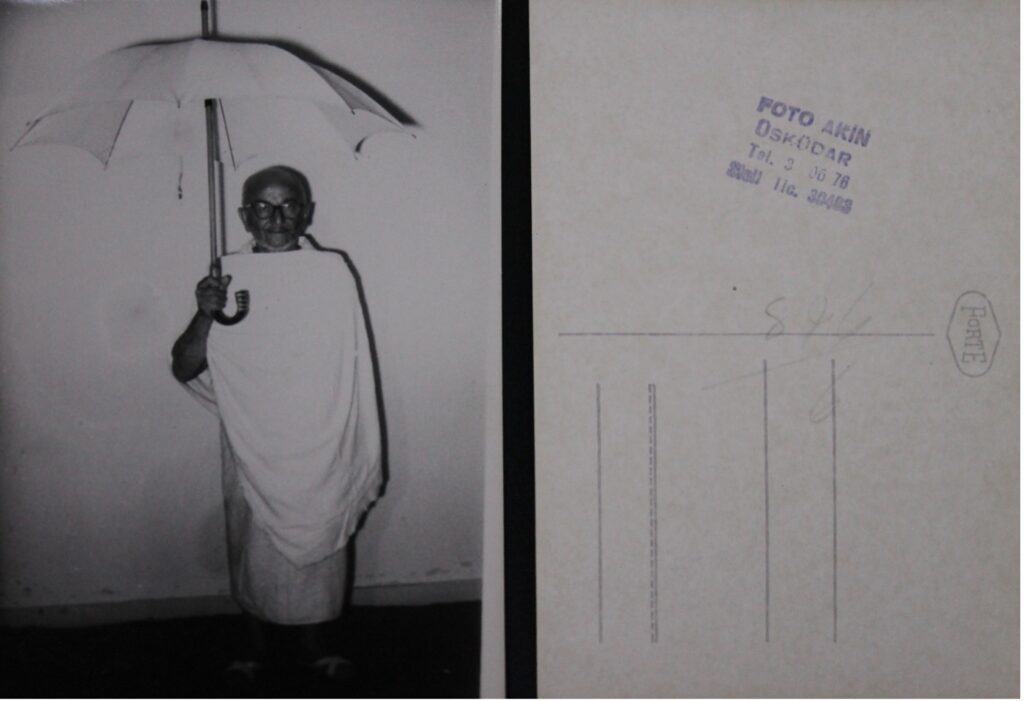

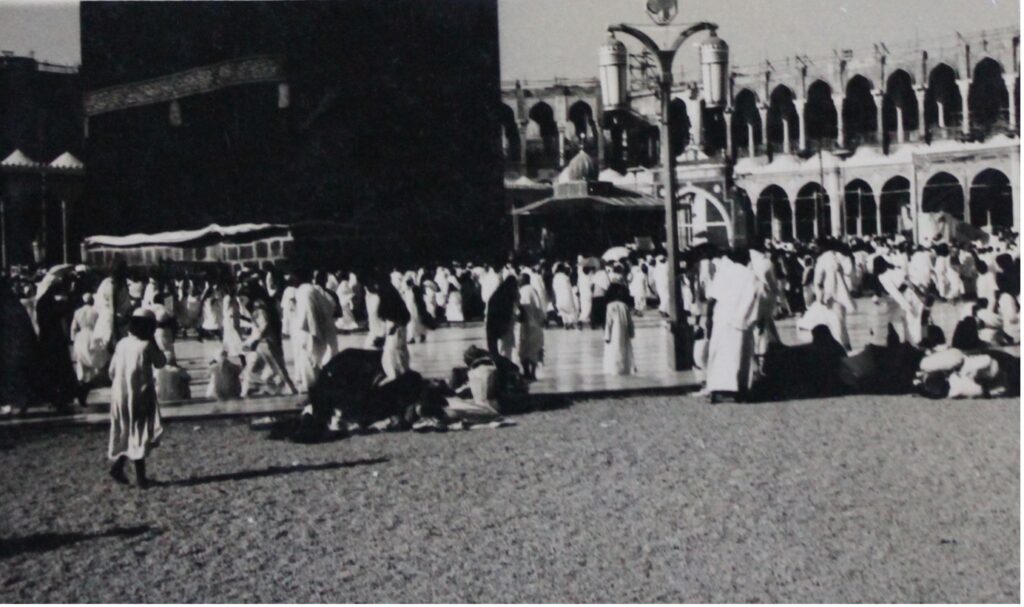

Pilgrims also commemorated their hajj by having photographs taken at studios in Mecca and Medina specifically set up for that purpose. Fatih Bey’s collection has several examples of Turkish visitors to the Holy Cities pilgrims donning local dress while posing in front of large illustrations of the Kaʿba and/or the Prophet’s Mosque (figs. 21 and 22). With photography still a prohibited practice in these sacred spaces, the studios represented the only option for pilgrims desiring a photograph by the Kaʿba. Some Istanbul-based entrepreneurs appear to have realised this, for Fatih Bey’s collection also includes a photograph of an elderly man in pilgrim garb – white ihram, flip-flops, and an umbrella to protect from the fierce Meccan sun – all taken at a studio in Üsküdar by the name of Foto Akin (fig. 25). While there is no way of knowing whether he managed to undertake the hajj after all, his pre-emptive souvenir testifies to another intriguing contemporary practice.

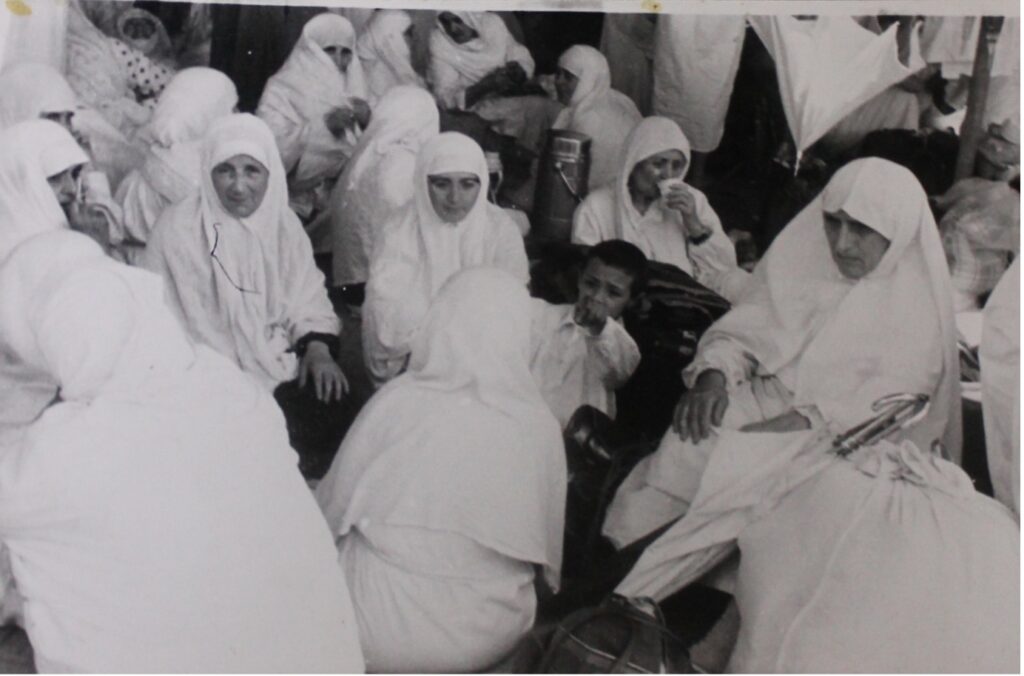

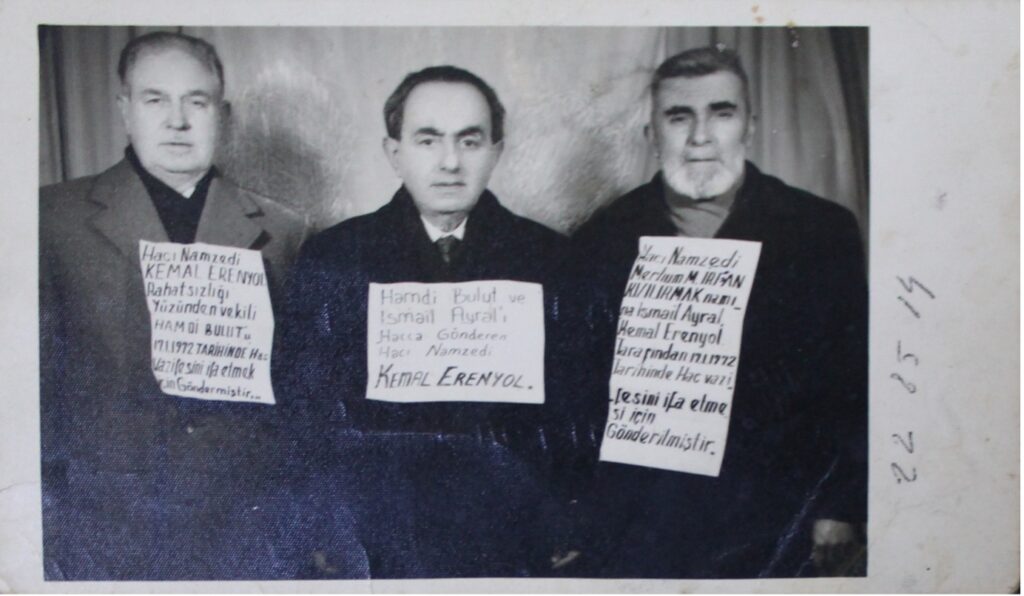

“Together, the photographs represent priceless fragments of journeys, spaces, and objects which in today’s world are no longer associated with the hajj.”Fatih Bey’s rich collection of photographs provide a unique insight into the hajj journey from departure to arrival and all that occurred in between. They show pilgrims spending time together and posing for photographs (figs. 26 and 27), as well as being welcomed back on their return home (fig. 28). In one somewhat eery photograph (fig. 31), a man unable to travel to Mecca is flanked by two proxy pilgrims, one of whom he deputised to undertake the hajj on behalf of himself and another whom he deputised to do so on behalf of a family member. Together, the photographs represent priceless fragments of journeys, spaces, and objects which in today’s world are no longer associated with the hajj.

The hajj between the Ottoman Empire and Republican Turkey

Just as an Ottoman pilgrim might have done in the sixteenth century, pilgrims four centuries later continued to bring home a diverse range of sacred cargo, including vessels of Zamzam water, shrouds that had been immersed in the Zamzam well, locally produced paintings, certificates, and models, dates from the orchards of Medina, and rosaries, soil, and wooden toothbrushes from both Holy Cities. Fatih Bey’s collection shows that these items continued to play an important role in everyday religion in modern Turkey.

The hajj in late 1940s–1960s Turkey was uncertain in more ways than one; it had been effectively proscribed for over two decades, the journey by land was not always stable, and the Holy Cities, along with the practices of the hajj itself, were modernising at seemingly breakneck speed. Yet some things that were true for pilgrims travelling from Ottoman Istanbul, Izmir, and Ankara continued to be so for those travelling from the same cities in the young Republic, as pilgrims continued to look for safety, comfort and security during their journeys, to find meaning in sacred stops along the hajj road, and even to benefit from the services of local delils in Mecca and Medina.

At the same time, the advent of air travel – expensive but becoming ever more accessible – made the rigours of the land journey less appealing and contributed in turn to the decline of sacred sightseeing along the Baghdad Road. With the journey to Mecca no longer an epic three-week expedition (not to mention the journey back via Damascus), the collecting of mementoes, the writing of letters, and the recording of memories all became somehow less meaningful. This likely became even more true once the Diyanet took over the management of the pilgrimage to Mecca in 1979, adding a new dimension to the regularisation of the hajj and the standardisation of its experiences. Of course, similar patterns can be seen elsewhere in the Muslim world. Yet, in these places, just as in Turkey, different elements of hajj culture have nevertheless been kept alive up to the present day.

Yahya Nurgat is a historian focusing on the early modern Ottoman world. His research interests include the history of Ottoman Islam, pilgrimage, and sacred space, as well as Islamic law and manuscript cultures. He holds a PhD from the University of Cambridge and is currently a postdoctoral research fellow at Sabancı University, Istanbul. His current project explores the role of law, authority, and sacrality in restorations of the Ka’ba in early modern Ottoman Mecca.

[1] Kemal Güran, ‘Hac,’ TDV İslâm Ansiklopedisi (https://islamansiklopedisi.org.tr/hac#7-cumhuriyet-donemi), last accessed 14.08.2023.