Introduction

I recently had the opportunity to attend the “Building BridgesSeminar” organized by Georgetown University and chaired by Daniel Madigan with the assistance of Professor David Marshall. The annual seminar started after 9/11 but has now moved into its twentieth year and has become more about theological discussions between Muslim and Christian scholars than reactions to current political events.

In contrast, Building Bridges seeks to understand texts within an interpretative tradition and those texts’ functional role within society and theology.

Moreover, the seminar is not an analysis of Muslim and Christian societies but rather oriented towards “believing academics” who speak from Muslim and Christian tradition on topics of mutual interest. Finally, it is not a summit of religious leaders seeking to produce a single manifesto of shared beliefs but rather, as the previous chair, the former Archbishop of Canterbury Rowan Williams noted, “improving the quality of our disagreements” such that participants truly understand what each group believes.[1] As Madigan explains, “the task before us, then, is to make that contention fruitful rather than destructive.”[2]

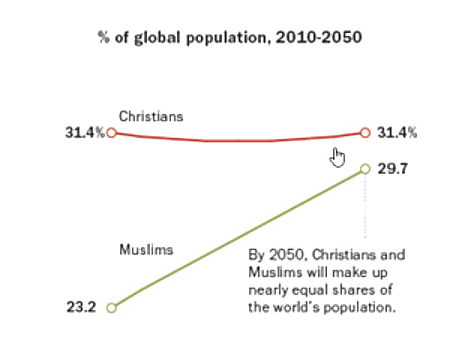

The initiative differs from others such as Scriptural Reasoning, which places “similar” texts side by side and has participants read them together. Such an approach naturally leads to reading texts through another scripture and a contemporary vantage point, rather than understanding the tradition from which the scripture itself emerges. In contrast, Building Bridges seeks to understand texts within an interpretative tradition and those texts’ functional role within society and theology. The texts anchor discussions that could otherwise diverge in a myriad of ways. The seminar additionally has remained a Christian-Muslim project and part of Christian-Muslim dialogue, itself an important subset of Interreligious Studies.[3] The fact that the seminar has focused only on Christianity and Islam is a reflection of the roles of these two religions in world peace and global dialogue, as demographic trends suggest the two religions will continue to be the largest and most demographically dominant.[4]

Relational Theology

The Seminar has a unique structure based on its belief of a “relational theology” or one that “recognizes that being in search of the one truth means also being in relation to those other seekers of the truth who do not believe as I do.”[5] Both groups are seen as “guests in God’s space” and believe that “something new in theology can emerge from the openness to mutual questioning.”[6] Participants do not simply engage each other through the lens of texts and theology but as people who are truth seekers and believers. This is one of the reasons why the seminar is often held in retreats where participants are encouraged to stay with other participants, eat together and socialize.

Participants do not simply engage each other through the lens of texts and theology but as people who are truth seekers and believers. This is one of the reasons why the seminar is often held in retreats where participants are encouraged to stay with other participants, eat together and socialize.

The concept of “relational theology” is connected to “interpretive hospitality” where various members of the different religions interpret the texts together.[7] “Interpretive hospitality” allows participants to be invited “into our questioning, not just into our answers.”[8] Participants learn about each tradition in all its complexity rather than simply through dogmatic terms.[9] Therefore, the seminar naturally attracts participants who are willing to provide scholarly contributions, listen to others and offer reflections and feedback.

A typical day focuses on a particular tradition, starting it with a presentation from a scholar in that tradition and then an introduction to texts related to the seminar’s theme.[10] The approach allows participants to immerse themselves in one specific religion and see how believers and scholars engage with the tradition. As Madigan elucidates, “Building Bridges was more often concerned with a theological theme, and we came to realize it was necessary to explore the key scriptural resources of each tradition on their own terms”.[11]

Small Group Study

After the initial presentations, participants break into small preassigned groups that last the duration of the seminar. This grouping is a “key element” of the seminar and allows participants to dive deeper into the texts with scholars of both religions. Questions from members of another religious tradition often lead the scholars to look at their “own” texts in a different light, nurturing further scholarly production.[12] It also challenges the adherents of one tradition to explain it to those who do not subscribe to it, creating a unique point of reflection. Many participants are comfortable in explaining their tradition to members of their own faith but the new audience forces them to think in novel ways and makes them realize the gaps in their explanations and perspectives. The structure naturally leads to debates and discussion but as the various members observed, a new “understanding emerges after disagreement.”

It also challenges the adherents of one tradition to explain it to those who do not subscribe to it, creating a unique point of reflection.

The small groups made me more interested in Christian texts that I had heard of but had not studied in any depth. In particular, I was fascinated by the story of the “Prodigal Son,”in which a father accedes to the demands of his youngest son and gives him his inheritance early (before the father’s death). After the son leaves and squanders his fortune, he returns back to his father, upon which his father throws a party that involves giving his son his finest robe and slaughtering a fattened calf. However, this leads to resentment from the elder son who was loyal to his father, never leaving but faithfully serving him and not once demanding more than his share. Our facilitator, Susan Eastman, helped guide us through the passage, which led me to read her article on the story entitled “The Foolish Father and the Economics of Grace.”. As Eastman explains, “Instead, [the father] gives the gift of his relationship, of a home in which eventually the son may be able to be truthful about the past. He can do this because, in the economy of grace, there is enough and to spare – enough forgiveness, enough honour, enough clothing, enough food.”[13]

The parable made me reflect on the Islamic tradition, and its own stories about fathers, sons and sibling rivalry. For instance, in the famous story of Joseph/Yusuf, jealousy compels the brothers to throw Joseph into a well. For years thereafter, the father Jacob/Yaqub longs to be reunited with his lost son.[14] While a clear reconciliation exists in the Qur’anic story, the Parable of Prodigal Son leaves us wondering if such a settlement ever takes place.[15] Similarly, after the Prophet Muhammad returns back to Mecca victorious, he begins to give the spoils of war to the Meccans who actively worked against him, leading the Medinans to become resentful. The Prophet Muhammad then gathered the Medinans or “Helpers” and exclaimed “Are you not well content, O Helpers, that the people take with them their sheep and their camels, and that you take with you the Messenger of God unto your homes?” The question led the Helpers to reply, “We are well content with the Messenger of God as our portion and our lot.”[16] The Prophet Muhammad then returned back “home” with the Medinans even though he had grown up and lived most of his life in Mecca.

Conclusion

Through this entire process, what impressed me the most is how the seminar has grown beyond a reactionary model to one that focuses on topics of interest to both Christian and Muslims. While there is no doubt that the “world weighs heavy”[17] and that external politics find a way to seep into various sessions (for instance, my group brought up the Russian invasion of Ukraine), the seminar has managed to concentrate on themes relevant to both Christians and Muslims that will live beyond the current moment.[18] Moreover, the seminar was not conducted in apologetic or polemical tone; real debates emerged between the various participants but never in a hostile or antagonistic way. Rather the discussions arose out of curiosity and a true desire to understand the different concepts and religious traditions.

…the seminar was not conducted in apologetic or polemical tone; real debates emerged between the various participants but never in a hostile or antagonistic way. Rather the discussions arose out of curiosity and a true desire to understand the different concepts and religious traditions.

Christians and Muslims did not interrogate each other nor were they put in the awkward position of having to “defend” their texts. Such a position is often forced upon Muslims in minority contexts who feel obligated to defend certain Qur’anic verses or prophetic traditions, especially if they are used by extremist groups. On the contrary, intra-religious debates were sometimes more common and intense as members of the same faith disagreed on important concepts, themes and personalities. I look forward to seeing how Building Bridges continues to develop, and reading their various proceedings.

Younus Y. Mirza is a Visiting Researcher at Georgetown University and Director of the Barzinji Institute for Global Virtual Learning at Shenandoah University which seeks to improve America’s relationship with Muslim-majority countries. He is currently writing a book about the Islamic Mary. To learn more about his scholarship, teaching and speaking, please visit his website http://dryounusmirza.com

[1] Lucinda Mosher, “Preface: Fifteen Years of Construction: A Retrospective of the First Decade and Half of the Building Bridges Seminar,” Monotheism and Its Complexities: Christian and Muslim Perspectives (Washington D.C.: Georgetown University Press, 2018), XII and 170. While the conference does not publish statements, Mosher, who serves as the rapporteur for the Seminar does help publish the various proceedings. Also, see Lucinda Mosher’s “Getting to Know One Another’s Hearts: The Progress, Method, and Potential of the Building Bridges Seminar,” in The Character of Christian-Muslim Encounter: Essays in Honour of David Thomas, ed. Douglas Pratt, Jon Hoover, John Davies, and John Chesworth (Leiden: Brill, 2015). In the essay, Mosher makes important points regarding how the Building Bridges methodology and pedagogy can be implemented in the classroom and how the seminar could be adapted to various geographical locations and contexts.

[2] Daniel Madigan, “The Building Bridges Seminar: Interrogating the Category of Interreligious Studies,” The Georgetown Companion to Interreligious Studies, ed. Lucinda Mosher (Washington, DC : Georgetown University Press, 2022), 337.

[3] For more on Interreligious Studies and how Christian-Muslim relations fit within it see The Georgetown Companion to Interreligious Studies, ed. Lucinda Mosher (Washington, DC : Georgetown University Press, 2022); Interreligious Studies: Dispatches from an Emerging Field, ed. Hans Gustafson (Waco, Texas : Baylor University, 2020); Interreligious/Interfaith Studies: Defining a New Field, eds. Eboo Patel, Jennifer Howe Peace, and Noah Silverman (Boston: Beacon Press, 2018).

[4] The Future of World Religions: Population Growth Projections, 2010-2050,” Pew Research Center, April 2, 2015.

[5] Madigan 339.

[6] Madigan 339.

[7] These are the words of Miroslav Volf; Mosher (2018), XVIII.

[8] Madigan 338.

[9] I am paraphrasing the statement of Brandon Gallaher; Mosher (2018), XII.

[10] Regarding structure, Mosher explains “First, the passage under consideration is read aloud. Second, each group member mentions a word, phrase, or sentence he or she finds compelling or puzzling— with only a brief explanation for this choice. Third, after everyone has taken this opportunity, deep discussion of the passage ensues”; Mosher, XI.

[11] Madigan 338. For a discussion of Islamic theology in Western academia, see Martin Nguyen, “Modern Scripturalism and Emergent Theological Trajectories: Moving Beyond the Qur’an as Text,” Journal of Islamic and Muslim Studies, vol 1 (2016), 61–79.

[12] For instance, scholar of Islam Asma Afsaruddin notes, “in my most recent book, Contemporary Issues in Islam, I have devoted a whole chapter to the importance of cultivating healthy and productive interfaith relations in the 21st century”; Mosher (2018), XX.

[13] Susan Eastman, “The Foolish Father and the Economies of Grace,” The Expository Times 117, No. 10 (2006) pp. 402–405

[14] For more on this story, see my “Doubt as an Integral Part of Calling,” in Hearing Vocation Differently: Meaning, Purpose, and Identity in the Multi-Faith Academy, ed. David Cunningham (New York, NY, United States of America: Oxford University Press, 2018). Also, see my work on Biblical and Qur’anic figures, John Kaltner and Younus Mirza, The Bible and the Quran: Biblical Figures in the Islamic Tradition (London, UK; New York, NY, USA: Bloomsbury 2018).

[15] As Eastman explains, “We do not hear the end of this family story; it remains to be worked out in the communities of the church and of the world. Will the brothers be reconciled? Does the younger son complete his ‘repentance’ by accepting the free gift of reconciliation given by the father? Does the older son recognize and accept the father’s generosity and welcome his brother? In the arena of acceptance created by the father’s grace, do the sons come to see the destructive selfishness of their own attitudes and actions, to confess from the heart? Or do they coexist in a state of cold war, an orchestrated and carefully constrained dance around the hurts and bitterness that are the legacy of the past?”; Eastman, 404.

[16] Martin Lings, Muhammad: His Life Based on the Earliest Sources (Rochester, Vt.: Inner Traditions, 2006), 325.

[17] See Rachel S. Mikva, “Six Issues That Complicate Interreligious Studies and Engagement,” in Interreligious/Interfaith Studies: Defining a New Field.

[18] As Madigan states, “We have tried to avoid being drawn into that atmosphere of political contentiousness in order to contend with the deeper theological questions that long pre-date and will just as long outlast our current geopolitical situation”; Madigan 337.