In many post-colonial states, militaries are powerful political entities rather than professional bureaucratic institutions. The roles that were played by militaries during decolonization gave them a gateway to intervention in civilian politics for decades to come. Subsequently, rolling back the military to the barracks has been one of the greatest challenges for states undergoing democratization processes. The recent events in Sudan illustrate this challenge. On Monday October 26th, Lieutenant General Abdel Fattah al-Burhan led a military coup d’état, dissolving the transitional government, and arresting several of its civilian officials as well as leading members of civil society organizations. What explains al-Burhan’s decision, which occurred despite increased external pressure to respect Sudan’s democratic transition? The following article aims to explore that question in further detail.

Frequent Interventions

Sudan’s post-independence era has been characterized by a high degree of political instability. This unrest is demonstrated in the country’s oscillation between short periods of democratic rule and long periods of military rule. Military leaders overthrew all of Sudan’s three democratic governments through coups in 1958, 1969, and 1989, and subsequently ruled the country from 1958–1964, 1969–1985, and 1989–2019. Although these coups were often planned and carried out in cooperation with civilian forces, once power was secured military members always managed to marginalize their civilian partners to emerge as the de facto leaders. The 1989 coup was plotted by the Sudanese haraka or Islamic Movement who sought to use the military to disguise their role and avert international condemnation. Within just a few years, tensions surfaced between the military and the Islamists. By the end of the first decade, in 1999, the military representative, President Omar Hasan al-Bashir, successfully ousted the regime’s founding father and the Islamists’ chief ideologue, Hassan al-Turabi. Al-Bashir took control of not only the state but also the Islamic Movement. The majority of Islamists sided with al-Bashir and against Turabi, primarily because of the former’s control of the state and its powers and the latter’s domineering tendencies illustrated in his unilateral decision-making. Since he assumed leadership of the Islamic Movement in the 1960s, Turabi marginalized other senior figures in the haraka, making his rein uncontested. Turabi is responsible for developing the movement’s grand strategies and policies until his removal in 1999, including the 1989 coup. Hence, some Islamists viewed him as an obstacle to their own political aspirations and collaborated with al-Bashir to depose him.

“During the thirty years of military-Islamist alliance, very much led by the military in its last two decades, and represented by the National Congress Party (NCP), the state, including its bureaucratic institutions and economic sectors, effectively came under the NCP’s control.”

During the thirty years of military-Islamist alliance, very much led by the military in its last two decades, and represented by the National Congress Party (NCP), the state, including its bureaucratic institutions and economic sectors, effectively came under the NCP’s control. This was a result of empowerment policies or tamkeen that saw Islamists and their sympathizers implanted across state institutions, as well as patronage-based economic policies that favored regime partisans. Ultimately, the security forces, including the Sudan Armed Forces (SAF), General Intelligence Services (GIS), Rapid Support Forces (RSF – primarily composed of the Janjaweed militias leading the war on non-Arab Darfuris in the early 2000s), and the police were the largest beneficiaries, controlling 60 to 80 percent of the economy, including major industries such as gum, gold, and livestock.

Democratic Transition

In 2018, large-scale demonstrations erupted over worsening economic conditions, including shortages of basic goods. Central to protestor demands was the removal of al-Bashir’s regime and a transition to democratic rule. Finally, in April of 2019, al-Bashir was overthrown by fellow military men; according to some analysts, these military men acted against al-Bashir not because they supported change, “but because they feared it.” Continuing with efforts to impede change and protect military interests, the new governing Transitional Military Council (TMC) called for expedited elections that would only see a reincarnation of al-Bashir’s NCP come to power. Aware of other political parties’ grave disadvantage following two decades of debilitation by al-Bashir’s regime, the Forces of Freedom and Change (FCC), a political alliance of civilian and rebel groups that spearheaded the Sudanese revolution, demanded a transitional period to uproot al-Bashir’s regime and generate a more level playing field. On July 5th, 2019, after several months of sustained protests and international pressure, the TMC agreed to form a joint transitional government with civilians for a period of 39 months. The TMC and FCC signed the Constitutional Declaration Charter founding three transitional government bodies: the Transitional Sovereignty Council (TSC) as head of the state, the Cabinet as the executive authority, and the Legislative Council responsible for legislating and overseeing the executive. The TSC was to be composed of 11 members, five civilians nominated by the FCC, five selected by the TMC and an eleventh civilian member selected by agreement between the two. The Council was to be led by a military member for the first 21 months and by a civilian member for the remaining 18 months. The number of TSC members as well as the timeline of the transition period was subject to change as a result of a peace agreement signed with armed rebel groups in October of 2020, but all of its provisions remained intact, including the transfer of TSC headship to a civilian member.

The October 25th Coup

On October 25th, just days before the transfer of headship of the Transitional Sovereign Council to a civilian member scheduled for November 2nd, al-Burhan carried out his coup. He dissolved the TSC, as well as the executive and legislative bodies of the transitional government, and he arrested senior civilian officials, including Prime Minister Abdalla Hamdok. Leading up to the coup, military members of the TSC attempted to cast doubt over the transitional government’s credibility. The military blamed the transitional government for anti-government protests, a failed coup attempt, and exacerbating economic difficulties and ethnic tensions, all widely believed to be staged by the military itself to avoid the transfer of power to civilians. Mohamed Elfaki Suleiman, a civilian member of the TSC, stated that the military was initially aiming to keep power without a coup. The lifting of the blockade in eastern Sudan and decrease in prices of basic goods in the coup’s aftermath all point to the military’s efforts to sabotage the transitional government.

Coup Motivations

Holding on to power was the chief impetus for the coup. While the transitional period was meant to be about power sharing, there was little of it. During al-Burhan’s headship of the TSC, the military was in charge of important political decision-making, not the civilians. Matters of foreign policy and peace talks with armed groups, two key items on the political agenda, were led by the council’s military members. The military used these issues to strategically build internal and external alliances. Through his meetings in the region, al-Burhan found committed support from Egypt, the UAE and Saudi Arabia, all possessing a strong record of opposing democratic transitions in the region. Offering power-sharing to some rebel group leaders through the Juba Agreement, al-Burhan and his deputy, Lieutenant General Mohamed Hamdan Dagalo (known as Hemedti, who also commands the RSF), convinced them to not only forsake the revolution, but to turn against it. For instance, as a result of the Juba Agreement, Gibril Ibrahim, leader of the Justice and Equality Movement, was appointed Finance Minister, and Minni Minawi, leader of the Sudan Liberation Movement/Army-M, was appointed governor of Darfur.

“Holding on to power was the chief impetus for the coup. While the transitional period was meant to be about power sharing, there was little of it. During al-Burhan’s headship of the TSC, the military was in charge of important political decision-making, not the civilians.”After the Juba Agreement, both Ibrahim and Minawi, who were previously part of FCC, left the coalition to form the faction FCC 2, and called for the dissolution of the transitional government. Unsurprisingly, while al-Burhan suspended the governmental institutions stipulated in the transitional constitutional document on the 25th of October, he declared his compliance with the Juba Agreement.

The military’s hold on power ensures its dominance over two potentially threatening commissions created by the transitional constitution. The first concerns the commission charged with investigating the June Massacre of 2019 whereby security forces violently dispersed sit-in protests, killing more than 100 protestors, and assaulting and injuring hundreds more. During negotiations between the TMC and FCC around the drafting of the transitional constitution, the former insisted on immunity for its members from prosecution, while the latter strongly opposed such a proposition. Eventually, the parties agreed on “procedural” immunity to senior members of the council that would be subject to removal by a majority vote of the legislative body. The commission, which is yet to release the report, has faced public criticism for its delay. While Nabil Adeeb, the commission’s head, attributed the delay to logistical causes, he also spoke of potentially grave political repercussions upon the report’s publication, including a coup, suggesting that the delay was a decidedly political decision. Mr. Adeeb’s reticence stems from the fact that the report is expected to support the findings of other investigation efforts that pointed to Hemedti and his RSF for the massacre and its atrocities. The military fears a civilian-led transitional government will bring its members to prosecution pending the transfer of power.

Another reason for the military coup relates to the Empowerment Elimination, Anti-Corruption, and Funds Recovery Committee or the Empowerment Removal Committee (ERC). The Committee was tasked with dismantling al-Bashir’s ‘parallel state’ founded through tamkeen.

Another reason for the military coup relates to the Empowerment Elimination, Anti-Corruption, and Funds Recovery Committee or the Empowerment Removal Committee (ERC). The Committee was tasked with dismantling al-Bashir’s “parallel state” founded through tamkeen. A year after its founding, ERC was able to retrieve millions of square meters of residential and agricultural lands, over hundred companies and organizations, and large cash amounts. However, the commission faced notable resistance and efforts to undermine its credibility and obstruct its work. For instance, weeks before the coup, the High Court of the Appeals Department arbitrarily nullified the ERC’s decision on the removal of a large number of judges, prosecutors and other judicial employees for connections to al-Bashir’s regime, asking them to return to their jobs, despite the ERC’s legal supremacy over the court. In another more confrontational move, security forces withdrew their protection from the committee’s headquarters and recovered assets and sites, as well as personal protection from the committee’s members.

The military is concerned with the objectives and powers of the ERC. The agencies making up the broader security apparatus, including the SAF, RSP, GIS, and police, each of whom were pillars upholding al-Bashir’s regime, are yet to undergo restructuring. Furthermore, given their control over large swaths of Sudan’s economy, they have been most resistant to calls for transparency and reforms. Hence, in addition to annulling the articles concerning the division of power between the transitional government institutions in the constitutional document in coup declarations, al-Burhan also annulled those documents that detailed the formation of independent national commissions, including ERC and the committee on investigating the June Massacre.

Looking to the Future

This is not the end of Sudan’s transition. Negotiations are still ongoing between the FCC and TMC with international and domestic mediators. Although there are many legitimate reasons to exclude the military from power, the most evident of these is the lack of trust resulting from its connections to al-Bashir’s regime and its recent behavior, democratization processes, including democratic transitions and consolidation, are most successful when they are negotiated. Discussions between the military and civilians need to be candid and must directly address the most divisive issues of concern, particularly those of the June Massacre, the economy, and the RSF’s fate as an independent institution. These discussions will be difficult. Civilian members, with public support and international backing, need to negotiate from a position of confidence and strength. It seems that since the signing of the constitutional document, civilians in the transitional government pursued a less confrontational approach, waiting for the military to willingly transfer power. Hamdok, for instance, has been accused of irresolution and allowing military members to violate his jurisdiction, particularly with regard to foreign policy. The military on the other hand, needs to be open to genuine power-transfer. In the face of sustained international pressure and protests, it might do so.

* In a future essay, I will analyze how the 2019 coup, and the events that followed, affected Islamists’ position in relation to the Sudanese state and military.

Dr. Dalal Daoud is a visiting scholar with the Ali Vural Ak Center for Global Islamic Studies at George Mason University. She completed her doctoral studies at Queen’s University. Her research focuses on the intersection of political Islam and ethnic politics in Sudan and Turkey. Specifically, she examines ruling Islamists’ approaches to minorities while analyzing the roles of elite strategic calculations, institutions, and ideational commitments. Her broader research interests include ethnic politics, Islamist politics, as well as MENA and African politics. Her research has been awarded several external awards, including the Social Science and Humanities Research Council Doctoral Fellowship and the Ontario Government Scholarship.

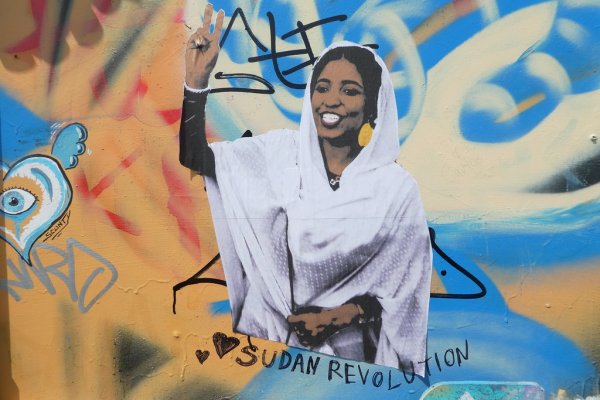

*cover image: This mural depicts Alaa Salah, whose image became a widespread symbol of the revolution outside of Sudan. Image “street art, Shoreditch” by duncan is licensed under CC BY-NC 2.0