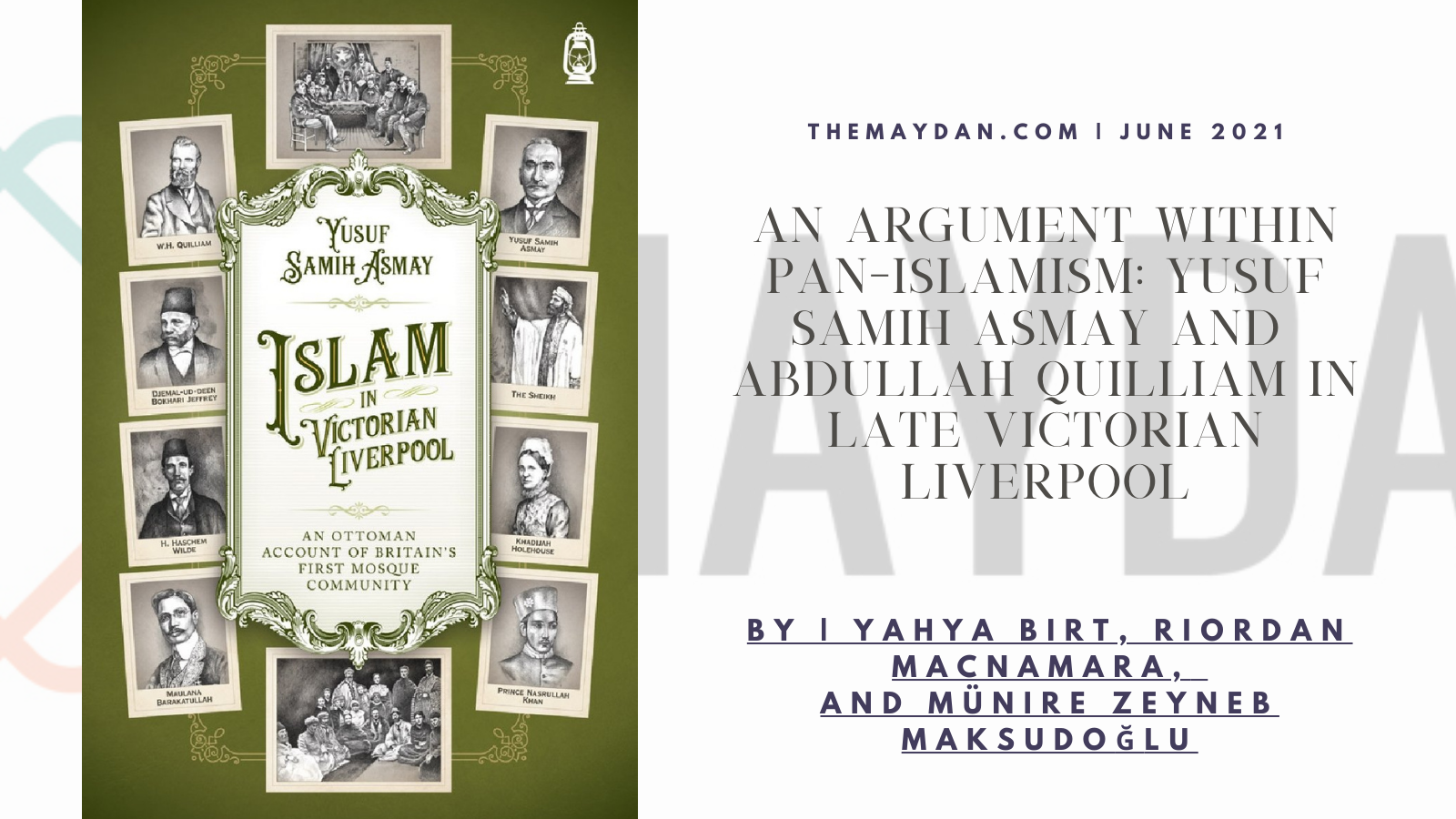

William Henry Abdullah Quilliam (1856–1932) was arguably the most prominent figure in nineteenth-century Islam in Britain. He declared his conversion publicly in 1887 and then for the next twenty years preached Islam in Liverpool, attracting hundreds of people to convert to Islam. He established the Liverpool Muslim Institute (LMI), centred around Britain’s first attested mosque community. Its novelty was skillfully exploited by Quilliam, both a journalist and lawyer by training, through the production of over 800 weekly issues of The Crescent between 1893 and 1908, which made the LMI known in the East.

Until very recently, scholarship on the LMI has relied heavily on Quilliam’s own publications to account for his life and that of the small Liverpool Muslim community. Yusuf Samih Asmay’s unique account, based on a 33-day research visit to Liverpool for which he deployed observation, interviews and post-visit correspondence, gives invaluable insights into Quilliam’s character but also into the everyday worship and religious practices of the LMI, which reflected significant religious syncretism between Protestant Christianity and Sunni Islam. He also provides eloquent witness to the great success that Quilliam’s propaganda had in the Muslim world and just how far and wide news of the LMI had spread in its heyday.

“His account allows us to eavesdrop upon the great Muslim debates about political and religious revival at the apogee of European colonialism but one conducted right at the margins of the umma, in a fledging micro-community of converts in Victorian Liverpool of all places.”

His account allows us to eavesdrop upon the great Muslim debates about political and religious revival at the apogee of European colonialism but one conducted right at the margins of the umma, in a fledging micro-community of converts in Victorian Liverpool of all places. Yet the success of Quilliam’s propaganda turned this seeming marginality on its head to reimagine Liverpool as an Anglophone nexus for pan-Islamism not just in the Muslim world but uniquely to the Muslim subjects of the British Empire itself, spread by print and steamship through its maritime trading routes.

Who was Yusuf Samih Asmay?

Yusuf Samih (d.1942) was born in Adana in modern-day Turkey. After completing his studies at the Köprülüoğlu Madrasa, Istanbul, he was appointed to an Ottoman-run school in Tanta, Egypt, as a Turkish-language instructor.

Asmay, as a translator and promotor of Ottoman Turkish as a centralising common language for Ottoman subjects, was concerned about Egyptian media being increasingly published in English, French, Italian, Greek or Armenian. Since the only Turkish–Arabic Egyptian newspaper, Vekayi-i Mısriyye, advocating Egyptian autonomy as an Ottoman dominion, had been banned by order of the Khedive (the Viceroy of Egypt), Asmay took the initiative in 1889 to produce a new pro-Ottoman newspaper Mıṣr, written in Turkish.

Besides journalism and language teaching, Asmay was a keen travel writer, visiting England three times between 1891 and 1895. Reports of his first journey were published in installments under the name Seyâhat-ı Asmay (Asmay’s Travels), before being published in book form in 1892.[1] His travelogue stands out for the severity of his criticisms of the British. For this Ottoman resident of British-ruled Egypt, Britons were hypocritical, conceited and harboured a deeply rooted aversion to Islam. He also discusses various British misrepresentations of Turkey, the Ottoman Empire, and the Islamic faith. During a heated discussion, Asmay blames folkloric Sufism (literally, “dervishness”, dervîşlik) and its “antics” (maskaralığı), and asserts that the reason Muslims have fallen behind the Europeans is the neglect and marginalisation of Sunni orthodoxy in their own societies.[2] A recurring literary technique of the time was for the Ottoman visitor to feign surprise and bewilderment upon encountering Western societies and mores, a playful clash of cultures intended to arouse the reader’s interest.

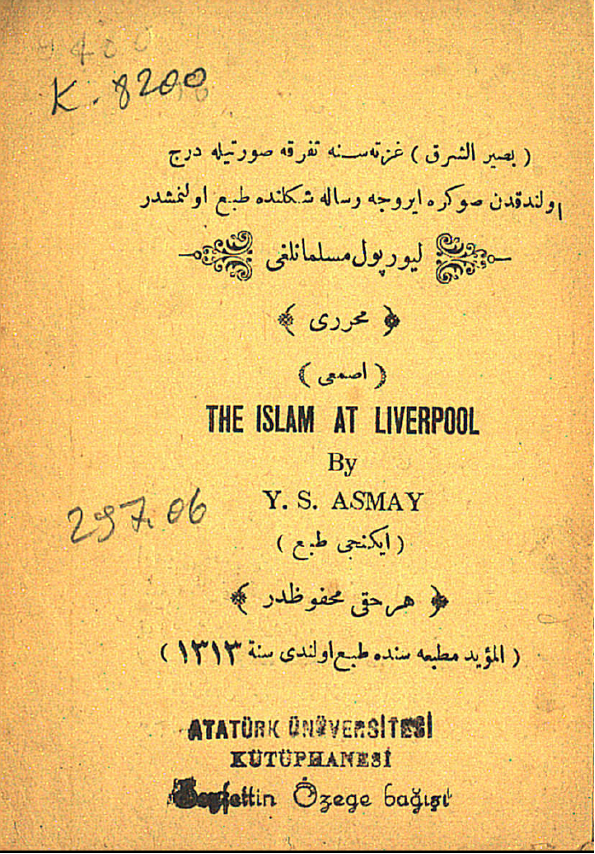

“The text we have translated and annotated in English is Asmay’s second travelogue, Liverpool Müslümanlığı, published in Cairo, of which a copy survives in Ankara University.[3] Unlike his 1891 journey to England, Asmay returned in 1895 with the stated purpose of visiting the LMI led by Abdullah Quilliam.”

The text we have translated and annotated in English is Asmay’s second travelogue, Liverpool Müslümanlığı, published in Cairo, of which a copy survives in Ankara University.[3] Unlike his 1891 journey to England, Asmay returned in 1895 with the stated purpose of visiting the LMI led by Abdullah Quilliam. This Liverpool sojourn was published in installments in a short-lived Egyptian pro-Young Turk periodical, Basîr al-Sharq, run by a certain Rashid Bey. It was then published in book form in 1895‒6 (1313AH) and went through at least two impressions.

Asmay’s Arrival in Liverpool

When Yusuf Samih Asmay came to Liverpool in July 1895, the LMI had just bid farewell to Nasrullah Khan (1874‒1920), the son of Afghanistan’s Amir Abdur-Rahman, who had been installed by the British Crown following the Treaty of Gandamak. The young Crown Prince had been officially invited to England by Queen Victoria in his father’s stead, as Abdur-Rahman was too ill to travel. The prince and his entourage of forty were greeted with formal honour and decorum at the LMI. Before leaving, he donated £2500.

“As a Cairo-based Ottoman, Asmay was familiar with the imperial politics of intrusion and interdependence, and understood the Khan’s gift as a political manoeuvre serving the purpose of aligning the interests of both countries, manifested by the Khan’s pecuniary involvement in the emergence of a British-led, Anglophile Muslim movement.”

As a Cairo-based Ottoman, Asmay was familiar with the imperial politics of intrusion and interdependence, and understood the Khan’s gift as a political manoeuvre serving the purpose of aligning the interests of both countries, manifested by the Khan’s pecuniary involvement in the emergence of a British-led, Anglophile Muslim movement. The Afghan Amir was staunchly opposed to the industrialisation of his country, which he saw as Western cultural intrusion. In his welcoming speech to Nasrullah (delivered in English, and in Persian translation by Maulana Barakatullah), Quilliam wove the imperial metaphor of “the sun of reason is darting its rays on the West, while the East is enveloped by the shades of tradition and imagination”, so that “steps should be taken to follow in the wake of Great Britain in matters of new sciences and arts”.[4] Asmay understood that Quilliam was taking a political position in favour of imperial British investment in Afghanistan.

Rather than offering direct criticism, Asmay highlights the discrepancies between the Khan’s favourable impressions of an orthodox Western Islamic movement and his own critical conclusions that the LMI was an unorthodox “fictitious thing.” In doing so, Asmay was indirectly undermining both the terms of this renewed partnership between the British Empire and its Afghan protectorate, and Quilliam’s interest in receiving recognition as “Sheikh al-Islam” from the Afghan court. Quilliam’s strategic goal was to bolster his own position as a mediating religious authority (“the Sheikh-ul-Islam of the British Isles”) between the British Empire, its Muslim protectorates and their subjects, and the independent Muslim states, the most important of which were the Ottoman domains.

Quilliam’s Unregulated Pan-Islamism

According to Asmay, instead of conforming to existing religious and political Islamic structures, Quilliam was developing a separate pan-Islamic network from Liverpool that lacked legitimacy. This assertion was not new. Prior to Asmay’s visit, Quilliam’s motives had been debated among Cairo’s intellectuals. For some, the LMI was yet another sly British gambit, a political attempt to undermine Islamic unity through propaganda about an English mosque with Muslim converts to buttress Britain’s imperial authority and subjugate Egypt’s colonised Muslims. For these detractors, the LMI’s hidden aim by associating Islam with Britishness was to counter Islam as a unifying anti-colonial force and to assimilate Muslims as imperial subjects. For an anonymous writer in Ahmad Urabi’s anti-British newspaper Al-Ustadh, the Institute was no more than a “political mosque located in Liverpool, the one built and made popular by the colonialists of Egypt, to deceive the Egyptians.” He added that, “It is better for you to chop your hand off than to place it in the hand of the [British] foreigner.”[5] Other Egyptians defended Quilliam as “honest” and the LMI as “praiseworthy”, calling on the Islamic principle of withholding judgment, that “there is no duty on us to judge others except by what is apparent.” The famed Egyptian reformer Rashid Rida even asked the same question of his teacher, Muhammad Abduh, to which the latter responded that the Liverpool mosque was not a political manoeuvre but genuinely Islamic as it had grassroots origins.[6]

While he does not mention this debate in his home city of Cairo, it seems unlikely that Asmay was oblivious to it. As can be seen in his first chapter, he had followed news reports about the Liverpool Mosque closely, hearing “news of reservations from certain persons who deserve to be called precautious rather than nit-pickers” and suggestions that Quilliam had converted for financial gain.

“During his visit, Asmay comes to suspect that Quilliam’s motives have a political element. Like Quilliam, Asmay was a journalist and newspaper editor, and was well aware of the influence of print and its importance in the creation and transmission of new collective identities.”

During his visit, Asmay comes to suspect that Quilliam’s motives have a political element. Like Quilliam, Asmay was a journalist and newspaper editor, and was well aware of the influence of print and its importance in the creation and transmission of new collective identities. Asmay understood that Quilliam saw The Crescent as the means by which he could propagate the idea of a unified, British-led Islam:

In the whole world, according to Mr. Quilliam, it is only the publications of this printing press [in Liverpool] that will gather the ideas of Turks, Arabs, Persians, Indians, Afghans and other nations of Islam in one place thus making them one family. By its newspapers promoting the idea of Islamic unity all Muslims will be gathered under Quilliam’s banner, so that they will politically prevail over other nations.

Asmay writes that he immediately disagreed with Quilliam’s scheme, pointing out to him that the unifying language of Islam was Arabic and that the only legitimate leader could be the Ottoman “caliph of the prophet of the Lord of the Worlds.”

What may have been at play was an argument within pan-Islamism between Asmay and Quilliam, something that his account brilliantly illuminates. Pan-Islamism at the end of the nineteenth century was firstly imperial in both its framing and its political impulses in securing political rights, before it later became nationalist and anti-colonial.[7] “Pan-Islamism”, as the British coined it, “Islamic unity” as the Ottomans and Asmay termed it or “fraternal union” as Quilliam dubbed it ‒ was invoked within the logic of sustaining imperial order, whether by the British, the Ottomans or the pan-Islamists. The British sought legitimacy in the eyes of its 100 million Muslim subjects as a great pro-Islamic power, while denying Islam itself as a mobilising anti-imperial force;[8] the Ottomans used the language of Islamic unity both to bond its disparate subjects together and to protect Muslims outside of its domains where it could through the limited means of recognition and patronage at its disposal. However, the Sublime Porte did not want to unduly antagonise the British, who had moved away from their alliance with the Ottomans after 1878. What most pan-Islamists shared at the time was a vision that a British–Ottoman concordat could be revived. It was in this strange conjunction of clashing imperial interests that Quilliam’s rather novel articulation of pan-Islamist dual loyalty was developed, and was indeed designed to operate within, given that he strove to carve out an authoritative mediating role as “Sheikh-ul-Islam of the British Isles” in the mid-1890s, a position from which both he and his community could benefit.[9]

“It was in this strange conjunction of clashing imperial interests that Quilliam’s rather novel articulation of pan-Islamist dual loyalty was developed, and was indeed designed to operate within, given that he strove to carve out an authoritative mediating role as ‘Sheikh-ul-Islam of the British Isles’ in the mid-1890s, a position from which both he and his community could benefit…”

However, Asmay saw dangers in Quilliam’s profession of dual loyalty to Crown and Caliph, as a political stance that granted Britain too much legitimacy in its existing imperial domains, which Asmay increasingly wanted to contest in Egypt, as his later involvement with Mustafa Kamil and Egyptian nationalism shows. While Quilliam was famously willing to publicly contest British imperial extension into Sudan in 1896,[10] he offered muted criticism of the British in Egypt, which lay at the heart of Asmay’s disagreement with Quilliam’s form of Anglophile pan-Islamism, whose rationale he expresses most completely in his presidential address at the Institute’s 1896 general meeting:

I believe in the complete union of Islam, and of all Muslim peoples; for this I pray, for this I work and this I believe will yet be accomplished. In England we enjoy the blessed privilege of a free press, with liberty to express our thoughts in a reasonable way, and this advantageous position can be used for the purpose of promoting the entire re-union of Muslim peoples. […] From Liverpool our steamers and trading vessels journey to each part of the world, and here within the walls of this Institution who knows but that the scattered cords may not be able to be gathered together and woven into a strong rope, Al-Habbulmateen, of fraternal union.[11]

Quilliam saw his position in Liverpool as a genuine opportunity, for himself, for his community and for Islam: to advance an Anglophone pan-Islamism centred around the British benefits of freedom of speech and non-sectarian religious freedom.

Both Asmay and Quilliam believed that the umma could use Western advances to its profit, but they clashed over how to bring this about. Despite being marginal Muslim neophytes in a distant imperial metropole, Quilliam assumed that he and other British converts should take a leading role. These white Victorian converts were not only fascinated by the exoticism of non-Christian cultures and traditions, but found the adoption of this oriental otherness more palatable if they could project a rather fantastical form of leadership over non-white Muslims, particularly over Her Majesty’s imperial subjects within the imperial British domains. After all, Quilliam’s designation as “Sheikh-ul-Islam of the British Isles” came about through nomination by Maulana Barakatullah (1854‒1927), a highly itinerant and prominent pan-Islamist and radical anti-imperialist of the early twentieth century, who at that time lived and worked in Liverpool as Quilliam’s secretary and fundraiser, and election by LMI members at a meeting in Brougham Terrace in October 1894; there is no hard evidence to date that the Ottomans ever formally recognised the title or that its officials ever used the title in connection with Quilliam.[12]

“After all, Quilliam’s designation as ‘Sheikh-ul-Islam of the British Isles’ came about through nomination by Maulana Barakatullah (1854‒1927), a highly itinerant and prominent pan-Islamist and radical anti-imperialist of the early twentieth century, who at that time lived and worked in Liverpool as Quilliam’s secretary and fundraiser…”

In asserting his leadership, Quilliam did not shy away from equating the origins of the Liverpool convert community with the struggles of the first Muslims in Mecca, who were persecuted and marginalised in their own society. In his 1896 annual speech, he makes an explicit parallel between nineteenth-century Liverpool and seventh-century Mecca:

Just as our glorious Prophet had the assistance of Abu-Bekr, Ali, Omar and Othman, and they were aided by Khaled and Saad, so in this work of planting Islam in England has your president been assisted by Nasrullah [Warren], by Haschem [Wilde], Abdur-Rahman [Holehouse] and many others, and if we are to search for further parallels we can find them between Billal, the first muezzin of Islam, and our own, Hassan Radford, who has frequently in times past boldly given the azan amidst a shower of stones flung at him by fanatical giaours.

Quilliam’s evocation of Liverpool as Mecca met with strong approval and sustained applause from the assembled LMI members, but Asmay, like some others, saw such pan-Islamism unregulated by the Sublime Porte and open to British interests as dangerous.

Consequences and Significance

The serialisation and then publication of Asmay’s polemical pamphlet precipitated a temporary crisis of legitimacy both for Quilliam and the LMI. Asmay’s critique hastened the formalisation of the Institute’s governance and provided at least the appearance of greater transparency, although run on British associational lines rather than on the Ottoman endowment model that Asmay advocated.

The other main effect was that publicised foreign donations to the LMI largely dried up after 1895. Before 1896, Asmay’s investigation found that Quilliam received between £7000‒11,500 in donations, from Afghanistan, British India (Hyderabad, Bombay and Rangoon), Istanbul and Lagos; Quilliam, when questioned directly by Asmay, only admitted to minor success and great personal expense and inconvenience. According to the LMI’s published annual reports, only £41 was received in publicised foreign donations between 1896‒1906. The LMI’s subsequent campaign to raise £6000 for a purpose-built mosque was a casualty of this diminution in foreign financial support. In 1903, the report of the annual meeting lamented that,

Some day the Muslim world would appreciate the great mistake they were making in not upholding the hands of the Sheikh in England…. Had the Sheikh been given proper financial aid from the Muslims abroad that he deserved, Islam could have been introduced and secured converts in every large city in the British Isles.[13]

After this mournful complaint, the Institute’s finances were no longer mentioned in The Crescent’s sporadic reporting of its final annual meetings (1904‒8).

“Twenty-nine days after Quilliam’s private audience with the caliph, the Ministry of the Interior issued an order to the Ministry of Foreign Affairs to ban Asmay’s Islam in Liverpool within the Ottoman domains, as it contained ‘harmful contents.'”

This episode had a final codicil. Quilliam had a private interview with Abdulhamid II on 2 May 1898 and reported that the caliph had told him that “the success of Islam in the British Isles lies very near to His Majesty’s noble and generous heart.” His second, successful trip to Istanbul was crowned by the caliph awarding him the Order of the Osmanieh (fourth class) ten days later, a prestigious honour normally given to civil servants and military personnel for services to the Ottoman state.[14] Twenty-nine days after Quilliam’s private audience with the caliph, the Ministry of the Interior issued an order to the Ministry of Foreign Affairs to ban Asmay’s Islam in Liverpool within the Ottoman domains, as it contained “harmful contents.” The plainest explanation is that Quilliam was able to appeal directly and successfully to the caliph for renewed recognition and support over the heads of any critics of the LMI. It might therefore be surmised that Quilliam asked for Asmay’s book to be banned and that the caliph granted his request. That said, as the order does not give any detailed rationale, it should be noted that there were many reasons why the Ottomans might ban a book, for instance, any book imported from outside the Ottoman domains would have its contents examined and assessed.

“When Quilliam departed from Liverpool for good, his son Billal closed the mosque and sold off Brougham Terrace. With no leadership or base, the LMI’s convert community collapsed, never to recover.[15]”

Two of Asmay’s predictions were proven to be correct. Firstly, that Quilliam and the LMI would be able to recover from these criticisms, not least because of the propaganda power of The Crescent and The Islamic World. Secondly, despite some of the reforms that were enacted after 1895, Asmay foresaw that without a firm and orthodox foundation in transparency and accountability, the Institute would not survive Quilliam’s departure. In 1908, this turned out to be true. When Quilliam departed from Liverpool for good, his son Billal closed the mosque and sold off Brougham Terrace. With no leadership or base, the LMI’s convert community collapsed, never to recover.[15]

Asmay’s Islam in Victorian Liverpool: An Ottoman Account of Britain’s First Mosque Community will be published by Claritas Books next week. It is translated with annotation and a critical introduction by Yahya Birt, Riordan Macnamara and Münire Zeyneb Maksudoğlu.

Birt is a community historian who has taught at the University of Leeds, Macnamara is a Senior Lecturer at the Institute of Cultural and International Studies, University of Paris Saclay, and Maksudoğlu is a PhD student of Early Modern Studies at the University of Sussex.

[1] Y.S. Asmaî, Seyahat-i Asmaî (Matbaatülcâmîa: Kahire, 1308AH/1892).

[2] For a translation into modern Turkish of Asmay’s Seyahat, see F.N. Şahin, Yüzyildan Bir Osmanli Seyahatnamesi: Seyahat-i Asmaî [An Ottoman Travels over the Century: Asmay’s Travels], unpublished MA Thesis, Dept. of History, Marmara University, 2010.

[3] The title was clumsily translated on the front page as The Islam at Liverpool (Liverpool Müslümanlığı), which we have rendered as Islam in Liverpool. Published in Cairo: Al-Muayyad Printers, 1313AH/1896CE.

[4] The Crescent (hereafter TC), 03/07/1895, p.5.

[5] Translated by A. Abouhawas in “An Early Arab View of Liverpool Muslims: Al-Ustadh and Sheikh Abdullah Quilliam between Accusation and Exoneration during the Age of British Imperialism”, EveryDay Muslim, 04/03/2020, https://www.everydaymuslim.org/blog/an-early-arab-view-of-liverpools-muslims/, accessed 14/12/2020.

[6] Idem, citing I.A. ‘Adwī, Rashīd Riḍā, al-Imām al-Mujāhid (Cairo: Mu’asasat al-Miṣriyya al-‘Āma li-Tālīf wa l-Anbā’ wa l-Nashr, 1964), A‘lām al-‘Arab, Vol. 33, p.96.

[7] C. Aydin, The Idea of the Muslim World: A Global Intellectual History (Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 2017), p.231.

[8] For more on the imperial promotion of Britain as the “greatest Muhammadan power” see F. Devji, “Islam and British Imperial Thought” in D. Motadel (ed.), Islam and European Empires (Oxford: University Press, 2014), pp.254‒68, although this was predicated on the British supersession of the Ottomans as the greatest champion of Muslim peoples rather than on rekindling a concordat between the two imperia as Quilliam hoped.

[9] Aydin, pp.65‒98.

[10] R. Geaves, Islam in Victorian Britain: The Life and Times of Abdullah Quilliam (Markfield, Leicestershire: Kube, 2010), pp.173‒88.

[11] TC, 29/07/1896, pp.905‒8.

[12] For an account of the meeting, see ‘A Manx Chief of Islam’, Mona’s Herald, 10/10/1894, p.5; for an exhaustive trawl through the Ottoman archives for how Quilliam was actually addressed by Ottoman officials, see M.A. Sharp, On Behalf of the Sultan: The Late Ottoman State and the Cultivation of British and American Converts to Islam, PhD Thesis, University of Pennsylvania, 2020, pp.128‒136.

[13] TC, 15/04/1903, p.237.

[14] TC, 22/06/1898, p.391; Matt Sharp notes (pp.72‒3) that Ottoman sources do not mention a private audience with the caliph but do confirm Quilliam’s receipt of the Order of the Osman.

[15] Geaves, Islam in Victorian Britain, pp.254‒8; J. Gilham, Loyal Enemies: British Converts to Islam, 1850‒1950 (London: Hurst, 2014), pp.117‒121.