The first version of this project was presented at the The Graduate Colloquium in Ottoman Studies August 2020 held online by The Institute of Middle East and Islamic Countries Studies at Marmara University and the Ali Vural Ak Center for Global Islamic Studies at George Mason University.

Persian travelogue writing experienced a significant rise during Iran’s Qajar period, and Iranian travelers produced hundreds of travelogues in this era. These travelogues narrated journeys occurring both inside and outside of the country. Some focused on remote countries such as America, Japan, and others on neighboring countries such as Russia. Although there have been some studies on the content of Iranian travelogues in Western countries, less attention has been paid to travelogues narrating journeys to the Ottoman Empire. As part of a new academic movement on Ottoman studies in Iran and Turkey, some works have been published on Persian Hajj travelogues. However, none of them have considered Persian Hajj travelogues as sources to study Iranian Hajj and Ottoman historiography.

“As part of a new academic movement on Ottoman studies in Iran and Turkey, some works have been published on Persian Hajj travelogues. However, none of them have considered Persian Hajj travelogues as sources to study Iranian Hajj and Ottoman historiography.”

For centuries, Iranian Hajj pilgrims used the routes within Ottoman territories to reach Mecca and undertake the rites of Hajj. A number of these pilgrims kept diaries on this long journey and produced many Hajj travelogues. These travelogues, mainly preserved in manuscripts in private collections and not cataloged, edited, and published until very recently, are invaluable primary sources to study the Ottoman empire because the travelogues describe the places Iranian pilgrims passed, the groups they associated with, and the bureaucracies they dealt with. In this article, I propose a new perspective in studies of the Ottoman Empire based on a close reading of this travelogue literature. To do so, I start with a general look at Persian Hajj travelogues and then discuss their contents as related to the Ottoman issues. Finally, I focus on the opportunities and challenges of using Persian Hajj travelogues to study the late Ottoman Empire.

Persian Hajj Travelogues: A General Introduction

There are some hundred Iranian Hajj travelogues written specifically on Hajj or including Hajj as part of the travelers’ journey to Europe or other parts of the world starting from the Safarnāma written by Nasir Khusraw (1003-1077) until the end of the Qajar era.

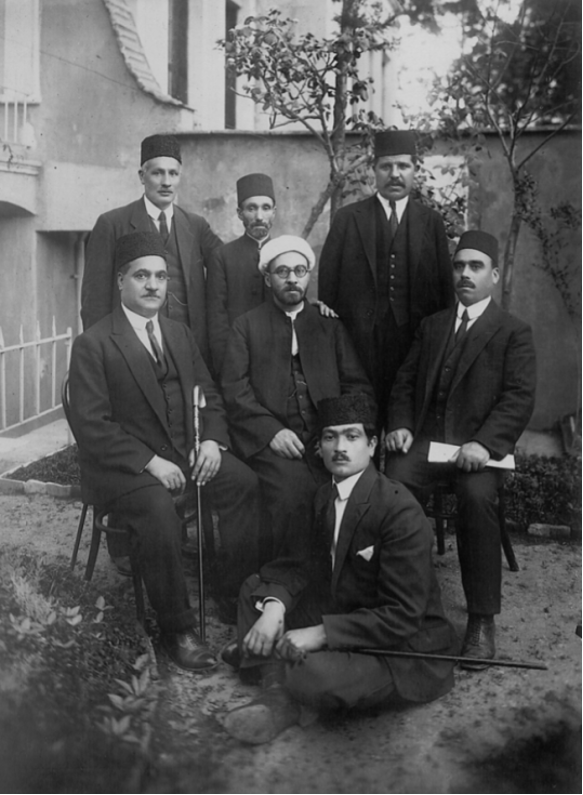

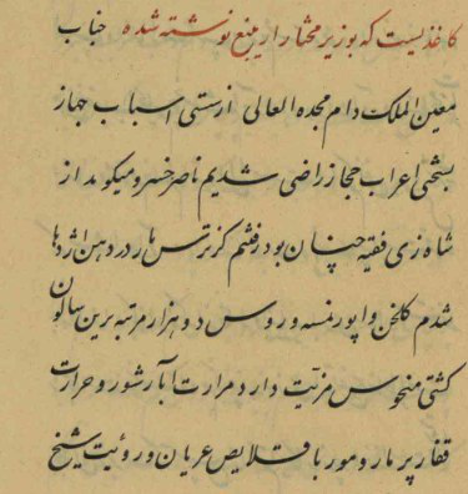

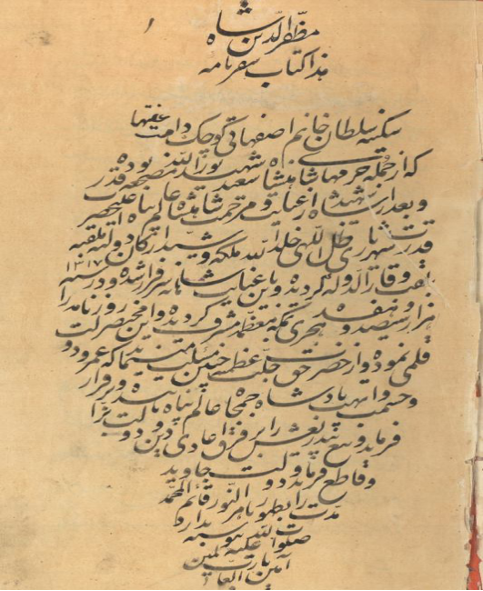

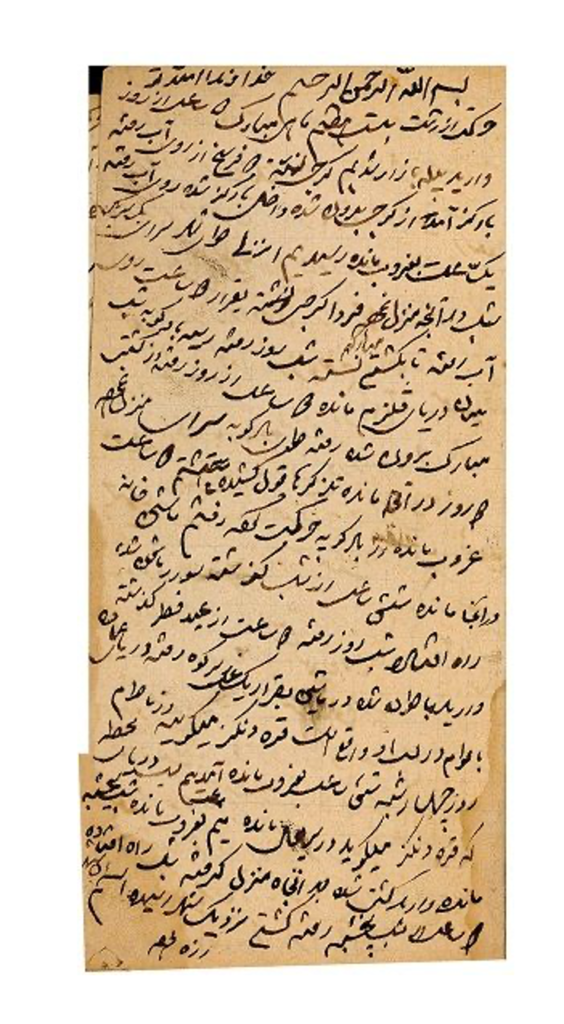

Writers of these travelogues were male and female, royal (Figure 1) and ordinary, merchant-class (Figure 2) and working-class, young and old, rich or poor. They travelled alone and as members of a group or familial community, and they were concerned with sharia and Sufism, Shi’ism, and Sunnism. Some of these travelogues are concise at no more than a page in length, while others are hundreds of pages long. They are written in very diverse styles: some are written as poems and others as prose. Most of the travelogues are structured in chronological order, starting with the pilgrims’ departure from home, explaining each or most of the essential stopping points, focusing on the Hajj rites in the Hejaz and the return journey home. Most of the pilgrims took notes while traveling and then wrote the travelogues later. Many of these travelogues, especially those written by notables and members of the royal family, were published as lithographs while their authors were still alive. Others were preserved in private and public libraries. Some of these diaries were later published while others remain as unpublished manuscripts. These works, even those written by dignitaries, present an understanding of Hajj far from the lens of what Eric Tagliacozzo calls the “official mind” in his studies of Hajj.

As authors of Persian Hajj travelogues differed in educational levels, social position, religiosity, and political approach, they also differ in their portrayal of the Hajj and the specifics they focused on (Documents 1, 2, and 3). Each of these travelogues exhibits sensitivity to particular matters and neglects others. Therefore, the Persian Hajj travelogues deal with a large number of religious and non-religious matters. Among the latter, there were issues related to social, cultural, and political points shedding light on the contemporary Ottoman state and society.

Currently, we have some 100 Persian Hajj travelogues written in the Qajar era. They have been edited and published in the past few years, and now they are available to use by researchers. The earliest piece in this long list of travelogues in the Qajar era is one written by Hedayat Ali ibn Sheikh Fadl Ali in 1825, of whom we know little. The list ends with Seyed Muhammad Hussein Taqawi Qazvini, a Shi’i clergyman who performed Hajj in 1922.

Types of Data of Relevance to Ottoman Studies

In this section, I explain the most critical data found in the Persian Hajj travelogue about the Ottoman state and society.

-

Ottoman Hajj and non-Hajj Travel Routes

Iranian pilgrims travelled to the Hejaz to perform Hajj using different routes. Among them, the sea route from the port located at the northern shores of the Persian Gulf to Jeddah, the Istanbul-Egypt route, the Iraq-Jabal route, and the Levant route were among the most popular. All of these routes were located inside the Ottoman territories. Although there have been different travelogue writing styles, they commonly share writing down most of the stopping point en route to Mecca. Different aspects of these routes, especially the infrastructure, are mentioned in these travelogues.

-

Ottoman Cities and Urban life

Persian Hajj travelogues are fraught with data about the Ottoman cities. Most of these cities are located along Hajj routes where Iranian pilgrims would have passed by or stayed for some days. More than other cities, there is information on Istanbul, Aleppo, Damascus, Cairo, Alexandria, Mecca, Medina, and Jeddah, found in the Persian hajj travelogues.

-

Ottoman Environmental History and Typologies

In the Persian hajj travelogues, there are many references to environmental issues in the Ottoman territories. Names and descriptions of mountains, rivers, animal life, and vegetation as well as the mutual relationships of the different ethnical groups within the Ottoman territories with them are mentioned in detail.

-

Ottoman Administrative Procedures

To travel through the Ottoman state, Iranians had to interact with the Ottoman bureaucracy, including the process by which they obtained permissions to enter the state and Tazkara. There is extensive data about the procedure of issuing these documents and their validity en route to Mecca.

-

Ottoman Structure of the Ottoman Mahmil, Amir al-Hajj, and Surriyi Humayun

Some of the Iranian hajj pilgrims attended the Ottoman caravan to Mecca each year. The caravan was called Mahmil of Sham and was directed by Amir al-Hajj. The Mahmil of Sham would carry the Surriyi Humayun, the Ottomans’ traditional annual gift to the Hejaz’s people and its governor. Iranian pilgrims extensively describe different aspects of this caravan and its trip from Damascus until it arrived in Mecca.

-

Ottoman Borders, Customs and Bureaucratic Issues

Within the Persian Hajj travelogues, there are many references to the Eastern borders of the Ottoman state. Iranian pilgrims entered Ottoman land through certain border points. Prior to entry, they had to pay to receive their visa, receive a document called Tazkara, and enter the state. The amount of money they had to pay, the material they were allowed to pass the borders, and customs laws are issues that one can find in these travelogues in detail.

-

Ottoman Health Issues and Quarantine Procedures

In certain years, pandemics spread across Hejaz. Therefore, all pilgrims, including Iranian ones, had to stay in quarantine stations while traveling by ships. These quarantine stations were erected by Ottomans or by their consent in different parts of the Middle East and North Africa. Quarantine stations in Beirut, the Suez Channel, and the Kamaran Island near Yemen were among those that Iranian hajj pilgrims had to stay in for some days. In their travelogues, they describe life inside the quarantine stations and the techniques used by health experts as part of the quarantines.

-

Ottoman Travel Security and Risks

A frequent theme in the Persian Hajj travelogues is the problem of security. Travelogue writers faced many risks, especially of being attacked by Bedouin tribesmen along the routes, as caravans were regularly attacked, killed, and looted by Bedouins. They also faced many natural challenges such as sea storms while traveling at sea and dust storms while crossing the desert.

-

The Dynamic between the Ottoman State and its Peoples

While traveling in Arab lands, the Iranian pilgrims were mainly under Ottoman state’s rules that were more and less not observed by the residents. Bedouins asked Iranians to pay a subsidy called “tax of brotherhood,” but the Iranian refused to pay and argued that they had paid the necessary taxes to the Ottoman state. The nature of these interactions can contribute to the general discussion on the Ottoman state’s relationship with its residents.

-

The Sharifs of Mecca: Sensitivities and Sectarian issues in the Ottoman era

The Sharifs of Mecca played an essential role in the Arabian Peninsula, especially in the late Ottoman period. Iranian pilgrims had excellent relations with the Sharifs of Mecca, and the Iranian Shah would often send some gifts to the Sharifs. This raises the question trans-imperial relationships between the Iranian state and the Ottoman subjects. There are details of Iranians and Qajar officers meeting with the Sharifs found in the Persian hajj travelogues and these can be considered a source on the historiography of Meccan Sharifs.

-

Iranian Communities and Shi’i Minorities Living in the Ottoman Territories

Some Iranian communities resided in different parts of the Ottoman state during the Qajar era. Among them, the communities living in Istanbul and Trabzon were more influential and significant. Iranian pilgrims would visit and stay with these residents while passing their time in the cities mentioned before. There are many descriptions of the Iranian communities’ social, commercial, and intellectual life in these Persian Hajj travelogues that makes it possible to rewrite the history of Iranian communities and Shi’i minorities living in the Ottoman territories.

-

Ottoman-Iranian Relations

The Iranian Hajj depended on the mutual agreements between the two states to allow Iranians to conduct Hajj. To ensure this agreement, certain negotiations and treaties were arranged to make it possible for the Iranian pilgrims to journey in Ottoman territories and perform the rites of Hajj. When Qajar notables were traveling to Mecca, they had frequent meetings with Ottoman notables and negotiated about issues related to Hajj and the Iranian pilgrims. Accounts of these meetings and decisions are found in the Persian Hajj travelogues in detail.

-

Iranian and Non-Iranian Hajj Pilgrims in the Ottoman Era

Drawing on the Qajar Persian Hajj travelogues, it is possible to roughly describe the general state of the Hajj in the late eighteenth and nineteenth centuries, including the Hajj experience for non-Iranian pilgrims. There are many references to non-Iranian pilgrims from other countries and ethnicities in these travelogues, especially those who seemed exotic to the Iranian pilgrims. An example is the issue of Sufi pilgrims from Central Asia who were participating in the Hajj pilgrimage and who sometimes joined Iranian pilgrims on the same ship.

-

Material and Non-Material Culture of Hajj in the Ottoman Era

Like other pilgrims, Iranian Hajj pilgrims had their own travel culture that can be called an “Iranian Hajj culture.” In its material and non-material forms, such as holding ceremonies on the martyrdom on Imam Hussein while travelling to Mecca or in return, visiting the Shii shrines located in cities where they pass and residing in the houses on Nakhawila, Shiis of Medina, are well mirrored in the Persian Hajj travelogues.

Conclusion

Persian Hajj travelogues are among the most important genres of travel narratives in Iran and one of the richest Hajj travelogue writings in the Muslim world. These travelogues are replete with data and references to different issues in an annual trans-border and trans-imperial pilgrimage. As Hajj necessarily took place in the Ottoman territory, Iranian pilgrims recorded their experience and understanding of the Ottoman world during their journeys. Therefore, these writings can be used as a primary source on the historiography of the Ottoman state. As many of these travelogues have been edited and published in recent years, the possibility of using them has increased a lot in the past years. These travelogues are not only useful sources on Ottoman historiography, but can be considered primary sources on the (mis)understanding the eastern neighbors of the Ottoman empire had about the society, culture, and politics of the Ottoman empire.

Peyman Eshaghi is a Ph.D. student of Islamic Studies at the Berlin Graduate School of Muslim Cultures and Societies (BGSMCS), Free University of Berlin, Germany. Before that, he studied at the University of Chicago, University of Ankara, and the University of Tehran in anthropology and sociology of religion. His main areas of research are hajj and pilgrimage in Islam and Iran-Ottoman relationship. Among his publications are Muslim Pilgrimage in the Modern World (co-edited with Babak Rahimi, Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2019), “To Capture a Cherished Past: Pilgrimage Photography at Imam Riza’s Shrine, Iran”, Middle East Journal of Culture and Communication, 8(2-3): 2015, 282–306 p. and “Quietness beyond Political Power: Politics of Taking Sanctuary (Bast Neshini) in the Shi’ite Shrines of Iran,” Iranian Studies, 49(3): 2016 (439-512). He can be reached at eshaghi@bgsmcs.fu-berlin.de.