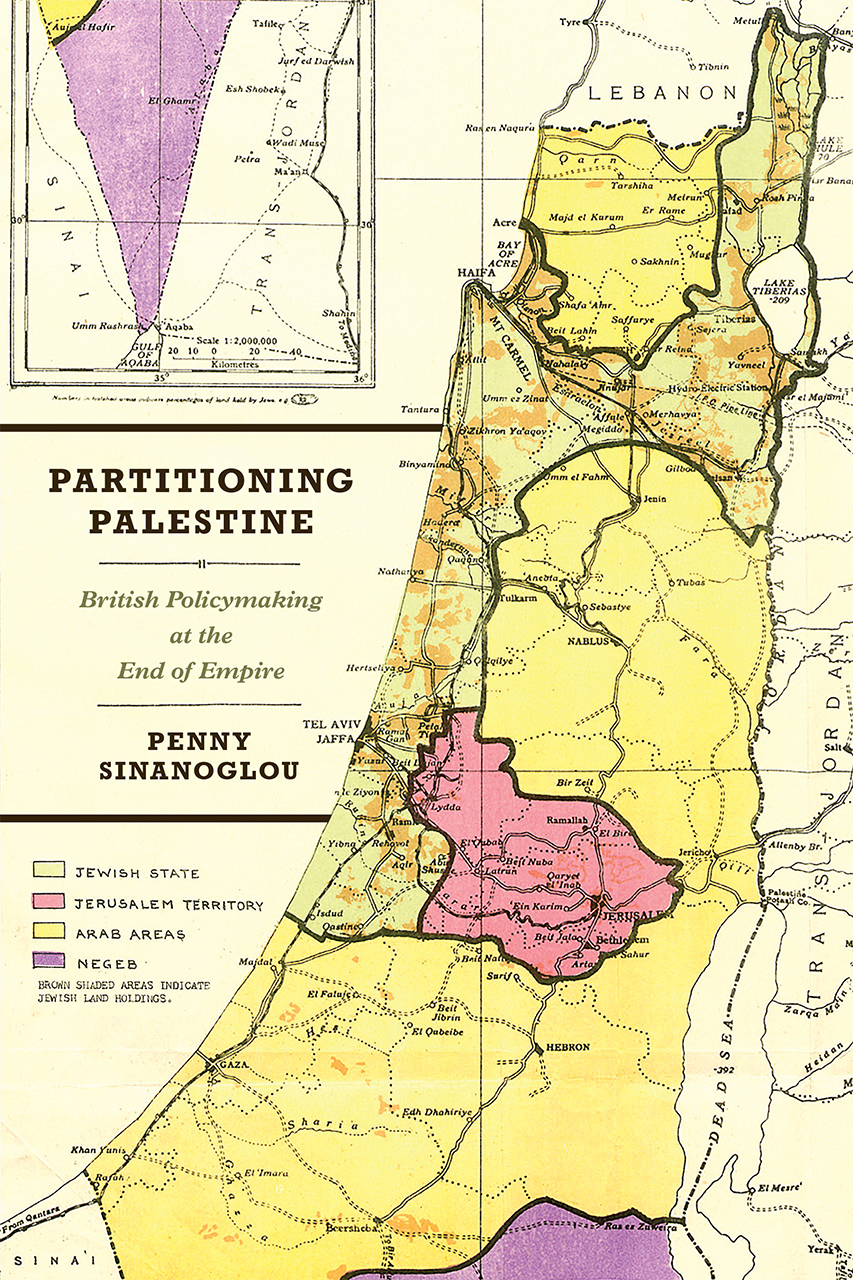

Book Under Review: Penny Sinanoglou, Partitioning Palestine: British Policymaking at the End of Empire (University of Chicago Press, 2020). ISBN: 9780226665788; 254 pages; $40.00 | Reviewed by: Kylie Broderick

Penny Sinanoglou’s Partitioning Palestine: British Policymaking at the End of Empire is a richly-researched book interrogating the legal and political mechanics of the British empire’s management of mandatory Palestine. The book dissects the British Empire’s attempts, and ultimately its failure, to accommodate conflicting prerogatives for establishing a “Jewish homeland” and for simultaneously creating an autonomous[1] and representative society, both outlined in the mandate’s charter. Among the myriad White Papers,[2] maps, commissions, and other tools the British drew on between 1920-47, Sinanoglou focuses on the Peel Commission (1936-39) as a crucial episode in which the British empire attempted to marry these prerogatives. In doing so, Sinanoglou emphasizes that British partition choices were not made in a vacuum. The mandate was legally beholden to the oversight of the League of Nations, managed through various bureaucratic offices in Britain, and mediated through the court of public opinion throughout Europe via popular news and journalism (133-134). They were also influenced by the undercurrent of the contemporaneously-occurring Great Arab Revolt in Palestine, which initially launched the Peel Commission and which challenged British population management strategies.

“There are three intertwining arguments informing the book. They follow the political, interpersonal, and geopolitical dynamics that conditioned partition’s rise to prominence and its fall as a viable political solution.”

There are three intertwining arguments informing the book. They follow the political, interpersonal, and geopolitical dynamics that conditioned partition’s rise to prominence and its fall as a viable political solution. The first is that the nature of the mandate’s legal charter and political ontology made its management, oversight, and reception inherently international. As Sinanoglou explains, the partition conversation was not only mediated between the British empire and the mandate territory, nor just between settlers, the indigenous population, and Britain. The political theater also incorporated international actors, including the League of Nations, European press bodies, and popular opinion across Europe and the Middle East. Those who drew, debated, and negotiated partition were themselves international men of the world, as figures like Reginald Coupland and Lord Peel of the Peel Commission had served as officials elsewhere in the empire, particularly India and Ireland (19). What they derived from their experiences there, particularly the utility of partition as a tool for controlling diverse populations, informed their agenda on Palestine.

Second, tension between the mandate’s prerogative to create an autonomous and representative society—intended to reflect the already-existing population on the ground—and the seemingly mutually exclusive requirement to fulfill the terms of the Balfour Agreement—to create a Jewish homeland—proved to be intractable. Settlers and mandate authorities usually did not consider a demographically coexistent nation-state to be viable. Therefore, various genres of partition, from Swedish-style cantonization (29) to hard borders (114), were proposed during the mandate’s initial days and were the preferred option until the end of the Peel Commission. British authorities drafted plans to ghettoize the native Palestinian population throughout their rule in historic Palestine. The various maps included throughout the book lend credence to the implicit logic of the settler-colonial playbook: maps drafted throughout the mandate consistently revealed British plans to accord Palestinians sub-optimal rights to land, water, and other resources (149). For the British, partitioning colonized territories throughout the empire had the dual benefit of ordering space and populations and making them more amenable to military control. It also made these populations receptive to the mechanics of the modern nation-state. These objectives took on increased importance for the British during the Great Arab Revolt, which they were attempting to curtail.

The third argument is that mandatory officials’ attempts to forge a solution were undergirded by an implicit animator: its desire to foment imperial control. Palestine was a political burden but also a potential boon in the eyes of the British empire. If the new state was constructed properly, it might fortify British control and expand its economic and political reach during the particularly crucial interwar moment (15) when attempting to build dependable supply chains. Whether British policymakers were advancing cantons, partition, or a unitary state, they were highly sensitive to the possibility that their plans might harmfully impact their geostrategic interests, “such as Christian holy sites, airfields, military installations, and a deep-water port in the Mediterranean… preserving ‘the security of the oil pipe line’ and ‘dealing with the maintenance of naval, military and air forces’” (67). In other ways, partition related to inter-regional geostrategic plans that the British were attempting to build. For instance, “Combining the Arab state and Transjordan was… an objective of many British policymakers, who saw such a unification as a way to retain access to critical geostrategic positions…” (171).

“On one register, this book tells the tale of the fragile hubris of empire, obsessively inward-looking, making sure no decision and policy proposed would ’embarrass’ (34-35) them and threaten their interests.”

On one register, this book tells the tale of the fragile hubris of empire, obsessively inward-looking, making sure no decision and policy proposed would “embarrass” (34-35) them and threaten their interests. They optimistically believed they could find a solution that would both make themselves “proud” in a paternalistic, pedagogical sense that reflected the “civilizing” mentality of late-imperial Europe and would simultaneously allow them to bolster their international strategic position. The Peel Commission was a prime example of an imperial optimism which ran headlong into reality: partition could not be conceivably accomplished without sacrificing some aspect of the mandatory charter. Palestine could not both become the site of a settler-colonial Jewish homeland and be set up with a representational government, as the Balfour decision itself was inherently made without Palestinian representational interests in mind. This rupture between the imperial optimistic imaginary and reality thereafter produced a complete policy turnabout via the Woodhead Commission, which heralded the death of empire-mediated partition as an option (130). As such, by tracking the British attempts to preserve their reputation and their power position, this book turns a trope of empire on its head and tells readers how manufacturing consent was to some degree necessarily built into this process.

“Scholarly audiences of both British imperial history and of modern Middle East history would be interested in reading Partitioning Palestine. In examining new evidence and rereading other well-referenced archival documents, framed within a compelling vision of the political and legal history of the Palestine mandate from within the field of British imperial history, Sinanoglou’s book is poised to make an impact.”

Scholarly audiences of both British imperial history and of modern Middle East history would be interested in reading Partitioning Palestine. In examining new evidence and rereading other well-referenced archival documents, framed within a compelling vision of the political and legal history of the Palestine mandate from within the field of British imperial history, Sinanoglou’s book is poised to make an impact. It presents a good deal of primary source information on which interested scholars could build their own future research. It also introduces new methods of interrogating imperial power in the early/mid-twentieth-century Middle East, rationalities that linger and continue to inform the settler-colonial present.

Sinanoglou’s presentation of archival evidence and her innovative argument pave new avenues for future research to continue to elaborate on how lynchpin mandate members saw the whole colonized world as one continuous opportunity to create entrenched economic opportunities and, to the extent possible, homogenize populations within newly-bounded nation states. At the same time, she observes that the British Empire was not all-powerful—it was susceptible to both being resisted and manipulated at key turns both by its international interlocutors in Europe and by Palestinians and Jewish settlers in historic Palestine. These observations remain crucial in understanding events unfolding in the settler-colonial present of occupied Palestine and the imperial context from which Israel was born.

“Future research could expressly draw links between the events in Partitioning Palestine and the present Israeli strategies of bantustanization and annexation of Palestinian lands using the thorough legal and political evidence Sinanoglou outlined in her book.”

Future research could expressly draw links between the events in Partitioning Palestine and the present Israeli strategies of bantustanization and annexation of Palestinian lands using the thorough legal and political evidence Sinanoglou outlined in her book. Historians could also elaborate on how British operators contended with legal traditions (Ottoman and local) already existing in Palestine in order to, for example, mete out land claims. Partitioning Palestine shows how multiple groups, indigenous and settler, interacted with, manipulated, or resisted British legal maneuvers. As such, future research could build on Sinanoglou’s work to further texture the complicated legal milieu that characterized the British Empire’s mandate in Palestine.

Kylie Broderick is a Ph.D. student and Mellon Fellow in modern Middle East history at the University of North Carolina, Chapel Hill. She is also the managing editor of Jadaliyya and a Co-Editor of the Resistance, Subversion, and Mobilization page. At the National Humanities Center, she teaches the Introduction to the Modern Middle East course. Her interests are in the political economy of the Middle East, as well as histories of gender, social mobilizations, and socio-economic class construction in Lebanon and Syria.

[1] Article 3 of the mandatory charter stipulates that the territory should strive for local autonomy pursuant to the goals of the mandatory system writ large. Article 6 details the demographic realities that autonomy in Palestine vis a vis settlement would entail.

[2] These were British policy papers usually issued after governmental investigations or commissions during the mandate period.

*The author first presented this review at Fourth Annual Graduate Students Book Review Colloquium on Islam and Middle Eastern Studies in 2020 organized by Ali Vural Ak Center for Global Islamic Studies at George Mason University and the Maydan in collaboration with the Fall for the Book Festival.