Though we conceptualize the political and the religious as distinct, in practice, they remain very intertwined, especially in many Muslim-majority countries. Understanding one is crucial in understanding the other. In the case of Muslim-majority countries, understanding the dynamics of the field of (interpreting) Islam is linked to an understanding of the wider field of power (or political context). That does not mean that the political ultimately determines the religious or vice versa. Instead, both mutually influence each other to different degrees based on the relative power of each in a specific historical context. The field of interpreting Islam is a diverse field in which many sub-fields, interpretations, schools of thought, and opinions reside. In more recent times, there have been two major axes of differentiation in the field: politics (activism-quietism) and tradition (traditionalism-Salafism-progressivism). Different scholars adopt combinations of these ideal types in various historical periods and geographical areas. The political authority also adopts certain interpretations and sponsors certain networks of scholars in different contexts, either for ideological or political reasons or both.

Even though my primary concern, as a student of sociology, is to develop a theoretical frame enabling us to deeply understand the divergent political orientations of scholars, I will leave this task until the publication of my MA thesis. Instead, my focus will be descriptive: drawing the maps of scholarly institutions. Moreover, while my MA thesis tackles scholars sponsored by Qatar, Turkey, and other countries, I will focus here on the United Arab Emirates-sponsored scholarly networks – Sufi neo-traditionalist and progressive anti-traditionalist. I hope this discussion would add some nuance to the debate on the role of religion and politics in the region in the wake of the UAE-Israel deal.

A Crucial Note

I feel the urge to emphasize some intellectual “warnings,” to avoid any misinterpretation of this piece. It is important to note that a state’s sponsorship of a network of a specific scholarly discourse does not necessarily mean that all scholars adopting that discourse are financially or otherwise sponsored by that state or are part of said state’s political project. In addition, though state sponsorship of such networks of scholars puts severe constraints on the latter and directs their scholarly work and discourse, the intellectual positions of those scholars should not always be reduced simply to state agendas. Furthermore, one should be aware of the level of dependence of each scholar on the state to be able to assess the impact of state policy on him/her. In other words, not all scholars participating in the activities organized by the state are necessarily equally dependent on and constrained by the latter. Moreover, the Sufi and progressive networks sponsored by the UAE are not the only groups under such influence. Other networks adopting varying discourses (e.g. Salafi or Ikhwani) are also sponsored by certain states and the dynamics shaping their experiences are comparable to those that I will discuss in this article. Finally, what I mean by “sponsorship” varies from symbolic appreciation to logistic support and institutionalization, providing platforms to job opportunities, and from promoting one’s ideas to granting him or her an official status.

The UAE’s Religious Policy

“While Yusuf al-Qaradawi was awarded by the UAE as the “Islamic personality of the year” in 2002, the UAE would include al-Qaradawi in its terrorism list fifteen years later. Two significant events have shaped UAE policy towards Islam in this period: September 11 and the ‘Arab Spring.'”The UAE had a shift in its religious policy. While Yusuf al-Qaradawi was awarded by the UAE as the “Islamic personality of the year” in 2002, the UAE would include al-Qaradawi in its terrorism list fifteen years later. Two significant events have shaped UAE policy towards Islam in this period: September 11 and the “Arab Spring.” By 2001, the UAE’s regional security was dependent on the US. But in the aftermath of 9/11, rather than “authoritarian allies,” the US started viewing the Gulf as a source of terrorism, exerting enormous pressure on Gulf states to take dramatic counter-terrorism and democratization measures. Domestically, the state imposed restrictions to prevent imams from giving talks related to politics in mosques and punished them in case of violations. Moreover, a crackdown on the UAE-branch of the Ikhwan, al-Islah, followed after they refused the state’s offer to cease their political activities and cut their relations with the international Ikhwan. Most importantly, the UAE firmly, though selectively, adopted the US policy of “promoting moderate Islam,” exemplified by Rand reports, that included promoting the networks discussed here. With the Arab Spring, a group of Islamists (belonging to al-Islah) and liberal intellectuals signed a petition directed to the UAE president and the Supreme Council of Rulers demanding democratization. Meanwhile, the Ikhwan rose to power in Egypt and Tunisia, alarming the UAE. In turn, the UAE would not spare any effort (including sponsoring scholars) that they thought would contribute to their goals of countering the Ikhwan and taking measures to prevent bottom-up democratic movements in the region to succeed.

“It is an irony that the UAE is sponsoring two Muslim discourses that reside on the opposite end of the axis of tradition: (neo-)traditionalism and anti-traditionalism (progressivism).The efforts of each are actually meant to negate the religious authority of the other … But what unites both discourses is their enmity to the activist Muslim discourses which the UAE severely antagonizes.“

It is an irony that the UAE is sponsoring two Muslim discourses that reside on the opposite end of the axis of tradition: (neo-)traditionalism and anti-traditionalism (progressivism). The efforts of each are actually meant to negate the religious authority of the other. But what unites both discourses is their hostility to the activist Muslim discourses which the UAE severely antagonizes. The sponsorship of such contradictory groups demonstrates that the UAE’s religious policy is not ideologically committed to any of these discourses. Rather, it seeks to make pragmatic use of both sides as tools in its fight with activist Muslim discourses and the “Arab Spring,” or for its international self-promotion. In the following, I will discuss briefly the history of UAE-based scholarly institutions and how they are relevant to the UAE’s agenda.

The Sufi/Neo-Traditionalist Network

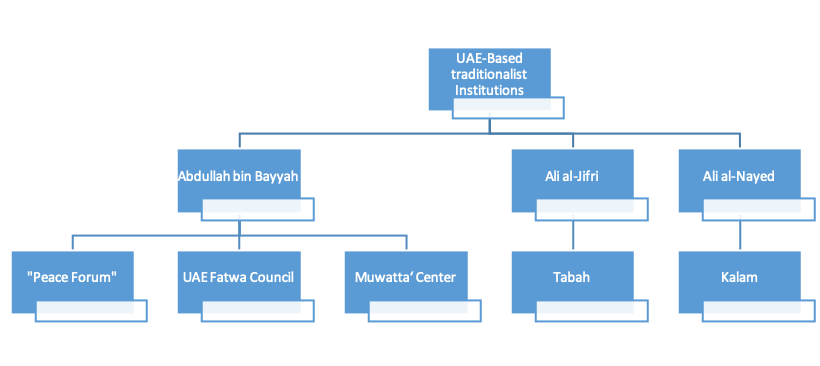

The Sufi neo-traditionalist network can be said to be the most sponsored by the UAE. The neo-traditionalist discourse emphasizes adhering to one of the traditional four schools of fiqh (jurisprudence) and one of the two schools of ‘aqīda (theology) as well as practising Sufism. For that, they consider themselves the true representatives of ahl al-Sunna wa-l-Jamā‘a (Sunni Islam) and the continuation of the Islamic tradition transmitted to them through an unbroken chain of transmitters. As “neo-traditionalism” doesn’t have an Arabic counterpart, neo-traditionalists are usually referred to as “Sufis” in the Arabic-speaking world. The most critical figures for the UAE-sponsored neo-traditionalism are al-Habib Ali al-Jifri – a Yemeni Sufi scholar from the Ba‘Alawi tariqa, Abdullah bin Bayyah – a widely-respected Mauritanian scholar, Hamza Yusuf – an American scholar and founder of the Zaytuna college in the US in 2008, and Aref Ali Nayed* – a Libyan scholar and politician who served as Libya’s ambassador to the UAE between 2011-2016.

The contact between the neo-traditionalists and the UAE rulers can be traced back to 2002 when al-Jifri started his preaching tours [jawla da‘awaiyya] organized by the UAE Ministry of Justice and Religious Endowments. In 2004, a bigger group of Sufi scholars were invited by the UAE to celebrate the birth of the Prophet (mawlid); among the group were the late Said Ramadan al-Buti – the widely-respected Syrian scholar whom the UAE chose for the Islamic Personality of the Year Award for that year – and Omar bin Hafiz – a prominent Yemeni scholar among the Ba‘Alawis. In 2005 a UAE-based institution was founded to be soon a center for neo-traditionalist scholars: Tabah Foundation. Headed by al-Jifri, Tabah quickly became vocal within the Muslim public sphere. After the Danish cartoon controversy in 2006, Tabah visited Denmark and invited Danish youth to the UAE to explain Islam to them (known as Litaʿārafū [so that you know one another] Initiative) by Tabah’s team.

Drawing a lot of attention, Tabah initiated Al-Mahaba Award whose festivals at the UAE in 2006 and 2008 were major cultural events in the Muslim world as many famous Muslim artists and public figures attended, in addition to the neo-traditionalist scholars assigned to the board of trustees like Abdullah bin Bayyah. In 2009, al-Jifri, on behalf of Tabah, visited Ali Gomaa – the then Grand Mufti of Egypt, Muhammad Tantawi – the then Grand Sheikh of al-Azhar, and Ahmed al-Tayyeb – the then president of al-Azhar University and the current Grand Sheikh of al-Azhar since 2010. Al-Jifri’s visits to Egypt would increase in the following years, especially after the “Arab Spring,” and he would come to reside in Egypt, becoming a public figure in the Egyptian public sphere and strengthening his ties with Gomaa, who became a member of Tabah’s Senior Scholars Council at least since 2010, and his student Usama al-Azhary, the Azharite scholar who is the advisor of religious affairs to Egypt’s former military head and post-coup president, Abdel Fettah al-Sisi. In 2009, another UAE-based institution called Kalam Research & Media (KRM), headed by Aref Ali Nayed, a later political figure advancing UAE’s agenda in Libya, was founded. KRM works with an impressively wide network exemplified by its Senior Consultant Scholars, and its activities and publications focus on Islamic theology and philosophy.

“After the July 2013 coup in Egypt, the UAE established institutions that were envisioned to ideologically legitimize the counter-revolutionary camp and delegitimize its dissidents (especially the Ikhwani and the Jihadists discourses).”

After the July 2013 coup in Egypt, the UAE established institutions that were envisioned to ideologically legitimize the counter-revolutionary camp and delegitimize its dissidents (especially the Ikhwani and the Jihadists discourses). Though such a mission was already pursued by Tabah since its inception, the UAE intensified these efforts through new institutions that focused on delegitimizing political activism, promoting obedience to the rulers, advocating the Islamic legitimacy of the modern state, and prioritizing peace over justice, among others. In 2013, the UAE set one of its most important neo-traditionalist institutions under the presidency of Bin Bayyah – the Forum for Promoting Peace in Muslim Societies (FPPMS). The Forum became a hub for some Muslim (and non-Muslim) scholars from all around the world in its annual conventions, published books and magazines, and sponsored initiatives and interventions in global Muslim affairs. At this stage, the neo-traditionalist discourse centered around the illegitimacy of the Arab Spring as they argued that political reform starts with a gradual spiritual reform rather than revolutions that undermine the stability of the societies.

Bin Bayyah soon would claim a much more central role in the UAE’s policy toward Islam as he became the chairman of the UAE Fatwa Council – an official body controlling fatwas in the UAE, which seems to have been established in June 2018 to increase Bin Bayyah’s authority and officiality. Hamza Yusuf is, notably, a part of this council and the Forum. The Fatwa Council was the third step after Bin Bayyah’s presidency of FPPMS and of al-Muwattaaʾ Center – a 2016-established scholarly institution aimed at educating UAE’s future religious scholars and officials and disseminating scholarly knowledge. In addition to its institutional support of such initiatives, the UAE granted these scholars wide media coverage, seeking to popularize their discourse in the Muslim world.

Al-Azhar and its “Grand Imam”

Though Ahmed al-Tayyeb and al-Azhar’s leadership can be considered traditionalist in their approach to Islam, they must be separately discussed as they are not very involved in the above-mentioned network, with the exception of some overlaps. The traditionalism of al-Azhar’s leadership stems from its thousand-year-old tradition, and its network is based on its distinguished position within Egypt and the Muslim World. The UAE has tried to exploit this respected position of al-Azhar as a soft power tool, and al-Tayyeb seems to be selectively responding to the UAE’s demands for maintaining the power of al-Azhar and protecting its leadership.

“Regarding the UAE’s sponsorship of al-Azhar, it seems that 2013 was the critical year of the UAE’s adoption of al-Tayyeb. The UAE awarded al-Tayyeb twice in 2013 the Sheikh Zayed Book Award’s Cultural Personality of the Year and Dubai International Holy Quran Award’s Islamic Personality of the Year.“

Regarding the UAE’s sponsorship of al-Azhar, it seems that 2013 was the critical year of the UAE’s adoption of al-Tayyeb. The UAE awarded al-Tayyeb twice in 2013 the Sheikh Zayed Book Award’s Cultural Personality of the Year and Dubai International Holy Quran Award’s Islamic Personality of the Year. Three months after al-Tayyeb’s UAE visit (for the Sheikh Zayed Book Award), al-Tayyeb stood beside the coup leader al-Sisi on July 3, 2013, legitimizing the coup as being “the lesser of two evils.” Al-Tayyib, however, protested the post-coup military’s lethal violence toward the anti-coup protestors by his statements and withdrawal from office to his village of origin. Al-Tayyeb’s refusal to receive his Dubai International Holy Quran Award’s Islamic Personality of the Year from the UAE, a few weeks after the coup, can be interpreted as a protest of the post-coup developments.

“The UAE’s sponsorship of al-Azhar is not just through the MCE, but also through the UAE Islamic Affairs and Endowment, which signed an agreement with al-Tayyeb in 2015 to open al-Azhar’s first abroad branch in the UAE. “

In July 2014, and based on the recommendations of the first conference of FPPMS, the UAE established the Muslim Council of Elders (MCE) that would be chaired, eventually, by al-Tayyeb. The MCE’s global reach is facilitated through regular meetings between al-Tayyeb and world leaders, sending Azharite “Peace Convoys” to preach “the human aspect of Islam” to 14 countries in Europe, Africa, America, and Asia, or acting as “Muslim elders” to advise on global Muslim affairs as in Burma or New Zealand. This global reach manifested in the MCE’s request for consultive status from the United Nations Economic and Social Council during al-Tayyeb’s meeting with the Secretary-General of the United Nations, António Guterres. However, al-Tayyeb’s 2019 meeting with Pope Francis in the Global Conference of Human Fraternity in Abu Dhabi is probably the MCE’s most celebrated event, depicted as “a historic meeting between the two most prominent religious leaders in the world.”

The UAE’s sponsorship of al-Azhar is not just through the MCE, but also through the UAE Islamic Affairs and Endowment, which signed an agreement with al-Tayyeb in 2015 to open al-Azhar’s first abroad branch in the UAE. Furthermore, the UAE also supports al-Azhar in Egypt by building new centers (like the Al-Sheikh Zayed Center for Teaching Arabic for Non-Natives) as well as a high-tech library with digitalized manuscripts. The UAE also provides wide media coverage for al-Tayyeb’s activities and promote his opinions through a TV program called “Al-Imam Al-Tayyeb” 2016-2020. More symbolically, the UAE rulers consistently show public respect to al-Tayyeb through kissing his forehead. Interestingly, the UAE is also reported to play a role in supporting al-Tayyeb in his cold war with al-Sisi. Particularly, the UAE pushed against a proposed constitutional amendment, discussed by the Egyptian parliament, by which al-Azhar could have lost its newly gained independence by re-giving the right to choose Sheikh al-Azhar to the Egyptian president rather than al-Azhar’s Senior Scholars Council.

The Progressive Muslim Network

The “progressiveness” of the scholars discussed here, despite their diversity, is related to their “revolution” against traditionalist interpretations of Islam. Taking mostly humanism and the Western epistemic experience as their base, such scholars propose new methodological tools for and interpretations of the Islamic sacred text. Different labels are used for such scholars: “modernist Muslims,” “liberal Muslims,” and “secular Muslims,” among others. The UAE-sponsored progressive figures include Muhammad Shahrur – a Syrian engineer known for his new interpretation of the Quran, Hasan Hanafi – an Egyptian philosophy professor known for his “Islamic Left” project, and Ali Esber (known as Adonis) – a Syrian secularist poet.

Khadeega Gaʿfar, an Egyptian researcher, reports how the UAE in 2007 was lavishly sponsoring young researchers to be trained in Shahrur’s new methodology of interpreting the Quran. Indeed, that was done through Shahrur’s short-lived Center for Contemporary Intellectual Studies (CCIS) which had branches in the UAE and Lebanon and aimed at training a generation of researchers to use Shahrur’s methodology and disseminate his ideas to the average Arab readers. In the context of the “war on terror,” Shahrur wrote Draining the Sources of Terrorism in the Islamic Culture that was published by CCIS in 2008.

“Khadeega Gaʿfar, an Egyptian researcher, reports how the UAE in 2007 was lavishly sponsoring young researchers to be trained in Shahrur’s new methodology of interpreting the Quran. Indeed, that was done through Shahrur’s short-lived Center for Contemporary Intellectual Studies (CCIS) which had branches in the UAE and Lebanon…“

As part of the counter-revolutionary wave, the UAE’s sponsorship of progressive scholars soared in 2013 with the launch of the Mominoun (believers) Without Borders (MWB) institution. Though it had branches both in the UAE and Morocco for six years, it is reported that the UAE recently shut down the Moroccan branch after political disputes with the Moroccan state (a claim denied by the institution). The MWB, in its self-description and publications, emphasizes the importance of critical approaches to the Islamic tradition and the centrality of humanism in these approaches. It seems to be very well-funded as it used to issue four free-online periodical journals and magazines, hundreds of books by hundreds of authors, and also organize hundreds of events in different parts of the world. It has an Egyptian branch, though with a different name: Daal. Having that many resources, the MWB revived many of the progressives’ legacies like those of Shahrur, Nasr Abu Zayd, Hasan Hanafi, Muhammad Arkoun – an Algerian professor known for his Islamic humanism and modernism project, and others.

“What is common among these progressive scholars and institutions has been their severe critique of ‘political Islam.’ MWB’s research agenda has been focusing on deconstructing Islamist thought, critiquing its content, and studying how to overcome it through writings and events.”

The UAE furthered its support for progressives by naming Shahrur among the winners of the 2017 Sheikh Zayed Book Award. UAE-based TV channels also gave space for Shahrur to disseminate his ideas in TV programs, despite the public controversy it caused in the UAE. Similarly, Adonis was given an increasing space in the UAE media and cultural public sphere as he participates in cultural events in the UAE and appears in its TV channels (like Sky News Arabia). It seems, though, that public anger prevented the continuation of his program in Ramadan 2019 on Abu Dhabi TV.

What is common among these progressive scholars and institutions has been their severe critique of “political Islam.” MWB’s research agenda has been focusing on deconstructing Islamist thought, critiquing its content, and studying how to overcome it through writings and events. Shahrour also published a new book in 2014, deconstructing the concept of ḥākimiyyah- which is believed to be a source of Muslim activism against the modern state. The anti-Islamist urge even exceeded intellectual debate to fabrication. The secretary-general of MWB- Younis Qandil- caused a public controversy after he cut and burned himself and accused “radical Islamists” for that. After investigations, the Jordanian authorities revealed that the accusation is false, and the event was fabricated.

Divergence and Overlap

This brief discussion of the UAE’s sponsorship of two polar-opposite networks of scholars starting in the mid-2000s points out to crucial nuances that underline how political calculations interact with the field of religious interpretation.

“While the Sufi and progressive networks sponsored by the UAE are not the only groups under such influence, understanding the diverse landscape of state sponsorship and its impact on scholarly positions is a first step in critically thinking about the interaction between politics and religious authority.”As mentioned above, political actors freely swing between interpretive frameworks that advance their agendas. Countering “political Islam” seems to be the only consistent line linking Sufi neo-traditionalism and progressive anti-traditionalism sponsored by the UAE. While the Sufi and progressive networks sponsored by the UAE are not the only groups under such influence, understanding the diverse landscape of state sponsorship and its impact on scholarly positions is a first step in critically thinking about the interaction between politics and religious authority.

Muhammad Amasha is a graduate student of Sociology and teaching assistant at Istanbul Şehir University, whose academic interests include political sociology, sociology of religion, sociology of art, and sociology of intellectuals. His current research focuses on two areas: the politics of the ulama and intellectuals, especially in the context of the Arab Spring; and the musical scene in the Arab world, especially mahragānāt music.

*Editor’s note: Aref Ali Nayed’s name was incorrectly written as “Ali al-Nayed” in the original essay. The error was corrected on 9/17/2020. We apologize to Dr. Nayed and to our readers.