*A slightly different version of this article first appeared in print in the Summer 2020 edition of Critical Muslim (35) which was commissioned as part of the Muslim Atlantic research project.

In his seminal book, The Black Atlantic, Paul Gilroy argued that models of cultural nationalism that are typically associated with ideas about individualised nation-states and national belonging present notions of difference that are immutable and cohesive, and which thus segregate people into mutually exclusive groups (Gilroy 1993: 2, 7). Accompanying ideas about exclusivity, immutability, ethnocultural purity, and ‘cultural insiderism’, the rhetorical strategy that defines identities as distinguished by absolute rather than relative differences (Gilroy 1993: 2-3), mask or negate the forms of interaction in the Atlantic world that produce intercultural and transnational formations and synergies. The misdirection of nationalist paradigms that promote exclusivity, immutability, and purity, and which become received, if misguided wisdom discourage alternative ways of understanding identity formation—notably the social construction of race and ethnicity—as produced through what Gilroy describes as ‘inescapable hybridity and intermixture of ideas’(Gilroy 1993: xi). To eschew cultural insiderism and its associated boundaries opens spaces for what Gilroy calls an ‘outernationalist’ revisionist approach. The contribution of this approach is no less than the revelation of what Gilroy defines as, ‘hemispheric if not global’ forms of consciousness, such as pan-Africanism and Black Power (Gilroy 1993:17). This approach constitutes a crucial challenge to assertions of uniformity and absolute, unqualified alterity, perspectives that divide nations and a nation’s peoples. Such an approach also drives Gilroy’s critique of the concept of modernity as it is deployed in nationalist historiographies and representations of nationality.

“This approach constitutes a crucial challenge to assertions of uniformity and absolute, unqualified alterity, perspectives that divide nations and a nation’s peoples. Such an approach also drives Gilroy’s critique of the concept of modernity as it is deployed in nationalist historiographies and representations of nationality. “

He offers a counterhegemonic configuration of Caribbean (Black Atlantic) modernity that probes political dialogues about power, agency, and autonomy (Gilroy 1993:187). For Gilroy, the idea of modernity is a particular kind of conceptual space, one that contains the drawback of serving as a refuge for black political culture when it is ‘locked in a defensive posture’ against the injustices of white supremacy (Gilroy 1993:188). When dedicated to origins, genealogical myths, and ‘ornate conceptions of African antiquity’, black consciousness is ever on the defensive, Gilroy argues, a posture that reiterates that ‘tradition’ and ‘modernity’ are polar opposites, the former inhabited by blacks and the latter by whites (Gilroy 1993:189). Tradition and modernity are thus separate barometers of value, measuring degrees of development, progress, and aspiration. In this context, an emphasis on tradition erases the Caribbean’s history of slave plantations; when tradition serves as an alternative to modernity, representing, for example, a refuge against the assaults of modernity’s racism, the debilitating aspects of the colonial past is sidestepped. In this usage the concept of tradition is ahistorical, Gilroy argues, denying slavery’s complexity and significance except as ‘the site of black victimage’ (Gilroy 1993:189), something to be escaped. Such a position denies the central role that plantation-based slavery played in modernity, as well as the hybridity and flux that produce intercultural and transnational formations and synergies. Instead, and quite mistakenly, regressive binary oppositions like ‘tradition’ vs ‘modernity’, ‘purity’ vs ‘impurity’, and ‘us’ vs ‘them’ are sustained.

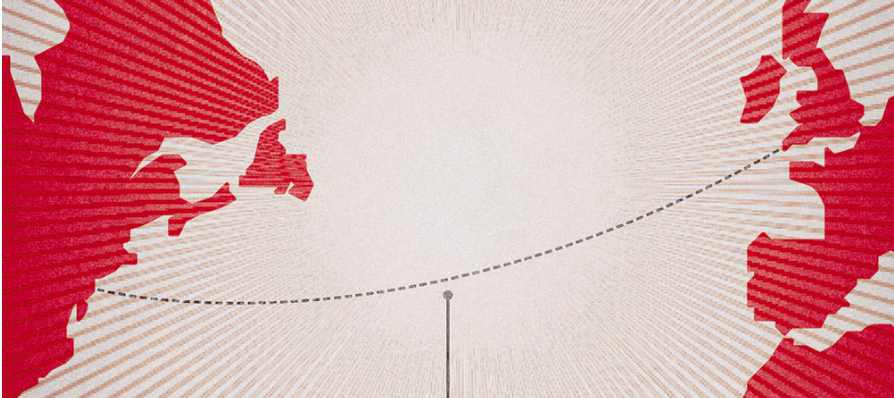

Like Gilroy’s vision of the Black Atlantic, the Muslim Atlantic is necessarily and by definition a phenomenon of diaspora. Both ‘Atlantics’ share empirical realities of passage and intermixture that are emblematic of this region’s historical experience and cultural production. As a conceptual framework, the Black Atlantic tells, or retells, a particular story, one born out of ideologies about inherent otherness defined by the boundaries of nation. The Muslim Atlantic has no single author, nor is it presently a cohesive conceptual framework.

“Like Gilroy’s vision of the Black Atlantic, the Muslim Atlantic is necessarily and by definition a phenomenon of diaspora.”Yet there are, as it were, the raw materials of history and some themes in this history, themes that intersect with those of the Black Atlantic and which may help to realise the Muslim Atlantic as a model of reality that we use implicitly to make sense of the existing external world, and a model for reality that is explicitly designed to imagine and organise that world (here I borrow from Clifford Geertz 1973). I am employing ‘realise’ in these two senses: to comprehend something and to achieve something. The remainder of my discussion will explore how the Muslim Atlantic might be realised, thinking in terms of such Black Atlantic foundational themes as nation, modernity, hybridity, race, sea passages, and sugar plantation heritage.

As historian Greg Grandin puts it, slavery was the ‘back door’ through which Islam came to the Americas (Grandin 2014:190). Although there is no consensus among scholars about the exact numbers of Muslims who crossed the Atlantic between 1501 and the end of the nineteenth century, estimations by Greg Grandin, Susan Buck-Morss, and John Tofiq Karam (Grandin 2014: 195; Buck-Morss 2009: 141; Karam 2015: 48) range from 4% to 20% of the approximately 12,500,000 Africans who were enslaved throughout the hemisphere (Karam 2015:48; Grandin 2014: 190). An important consideration in all of these estimates is the regions from which many of the enslaved were captured: Senegambia, Upper Guinea, Lower Guinea, and the areas around the Senegal and Gambia Rivers. Among the inhabitants who were Wolof, Fulani, and Mandinka, many, according to Karam and Grandin, were Muslim (Karam 2015:48; Grandin 2014: 190).

“An important consideration in all of these estimates is the regions from which many of the enslaved were captured: Senegambia, Upper Guinea, Lower Guinea, and the areas around the Senegal and Gambia Rivers. Among the inhabitants who were Wolof, Fulani, and Mandinka, many, according to Karam and Grandin, were Muslim (Karam 2015:48; Grandin 2014: 190)”But given the geographic range throughout West and Central Africa that these populations inhabited, as well as the ethno-linguistic group variations they represented, some scholars think in terms of Islam in the plural: a spectrum of Islamic beliefs and practices that went from coexistence with neighbouring animists and the amalgamation of pre-Islamic and Islamic practices, to jihadist orthodoxies exercised especially throughout the seventeenth to nineteenth centuries. Grandin describes this as a period rife with reformist jihads directed towards the culling and modification of various sorts of local religious syncretism (Grandin 2014: 191). Another consideration is that early generations of Muslims in the Atlantic world brought with them genealogies of fourteen centuries of engagement with the West, the last five of which included the Americas, which also involved other, New World peoples and cultures. This Muslim version of the Atlantic hybridity that is key to Gilroy’s formulation has been the subject of scholarly discussion about how and by whom ‘Muslims’ are defined, and how important heterodoxy and orthodoxy are in making these determinations (e.g., Khan 2012; Smith 2010; Shivley 2006; Ouzgane 2006; Gilsenan 1982). Even the term ‘Islam’ is itself a sizeable generalisation, encompassing, among other referents, Arab, Ottoman, North African, Spanish, Indian, and Far Eastern. And this, Jerry Toner writes, is just in the Old World (Toner 2013: 21).

These questions about the ways that hybridity can destabilise master narratives that definitively categorise religious traditions and those who adhere to them are complicated by the perspective of some scholars that in the Atlantic world, as historian Sylviane Diouf puts it, ‘Islam brought by the enslaved West Africans has not survived. It has left traces, it has contributed to the culture and history of the continents; but its conscious practice is no more’((Diouf 2013: 251). The significance of this disappearance from ‘collective consciousness,’ argues Diouf, is that enslaved African Muslims have been overlooked in the scholarship on Africa in the Americas (Diouf 2013: 275-276). Like all enslaved Africans in the Americas, Allan Austin observes, enslaved African Muslims remain in the vast majority anonymous, or, at best, named property on owners’ lists (Austin 1997: 3).

“Like all enslaved Africans in the Americas, Allan Austin observes, enslaved African Muslims remain in the vast majority anonymous, or, at best, named property on owners’ lists (Austin 1997: 3).”The public record of their persons and their lives is lost to history. Literary scholar and historian Allan D. Austin points out that African Muslims became slightly more visible in the United States about the time of the Civil War (1861-1865) but ‘a kind of suppression of information’ about them ensued, lasting for over a hundred years. Notable examples of this erasure are evident earlier in the 1856 American novel, Benito Cereno, by Herman Melville, who did not identify his main African characters as Muslims, although they were; in another 1856 American novel, Dred, A Tale of the Great Dismal Swamp, by Harriet Beecher Stowe, who also did not identify the protagonist, ‘Dred,’ as a Muslim, despite that his parents were Mandingo; and, finally, as Austin analyzes it, Toni Morrison was ‘curiously coy’ in her use of Muslim names for her characters in Song of Solomon, and did not acknowledge ‘their religious provenance that brought a Muslim spin’ to that novel (Austin 1997: 13. 17). One important consequence of these kinds of sidelining or erasure, for Austin, was ‘an early disidentification between Antebellum African Americans and Muslims’ that began to be lessened only with the rise of the Nation of Islam in the second quarter of the twentieth century (Austin 1997: 14)), or, as Sylviane Diouf has it, in 1913 with the rise of the Moorish Holy Temple of Science founded by Noble Drew Ali. A member of this temple was Wallace Fard Muhammed, who would later go on to found the Nation of Islam.

This issue about visibility and the relationship between Africans’ racial identifications and religious identifications in the Americas is yet another dimension of what we might call the survival problematic of Islam in diaspora. This survival problematic can feed the hybrid formations and intermixtures to which Gilroy calls attention, or cast them into doubt. For example, political scientist Ali Mazrui theorises that the Atlantic world’s African diaspora had ‘two routes toward re-Africanization’: one route was through Pan-Islam and the other route was through the Rastafari Movement. Islam took hold in North America and Rastafarianism took hold in the Caribbean (Mazrui 1990: 157). The reason that African diaspora communities in the Caribbean did not gravitate toward Islam are twofold, Mazrui contends. North American racial thinking collapses ‘black’ and ‘brown’ into a single category of identity, thus Muslims of various non-‘white’ heritages all could identify with Islam. By contrast, historically in the Caribbean, ‘race consciousness does not as readily equate Black and Brown’ as it has in the US. Counted as ‘white,’ Arabs in the Caribbean have been more privileged socially in terms of the structural inequality that characterises the region. Thus the Arab origins of Islam, Mazrui argues, were viewed as ‘being in conflict with Islam’s African credentials’; this did not encourage diaspora Africans to identify with Islam (Mazrui 1990:157). Diouf takes a comparable position about racial thinking and Islam but from a different angle. She argues that accepting enslaved Muslims as Africans would have threatened the North American racial order. ‘It was more acceptable to deny any Africanness to the distinguished Muslims than to recognise that a “true” African could be intelligent and cultured but enslaved nonetheless.’ (Diouf 2013: 102). This is not a case of diasporic Africans turning away from Islam, but such dichotomising could have contributed to subsequent conventional wisdom about the connection, or lack thereof, between Africans and Islam.

“A second reason for the lesser presence of Islam in the Caribbean is that along with the Levantine diaspora in the Americas, the mid-nineteenth century brought another population of immigrants to the Caribbean: indentured labour from the Indian subcontinent.”A second reason for the lesser presence of Islam in the Caribbean is that along with the Levantine diaspora in the Americas, the mid-nineteenth century brought another population of immigrants to the Caribbean: indentured labour from the Indian subcontinent. In the majority Hindu, they also included Muslims. Indians’ presence, which began in 1838 in then-British colony, British Guiana, gave rise to what would become a conventional association between Islam and Indians rather than Islam and Africans or Arabs. Mazrui sees the result of this subcontinental overshadowing being ‘a much slower pace of Islamic conversions among Caribbean Africans than among African-Americans.’ (Mazrui 1990: 157). This dominant, dichotomised representation of Caribbean Muslims as Indian and not as African did not produce a picture of uniformity in Caribbean Islam, however. Indian Muslims brought with them a range of schools of thought, including Sunni, Shi’a, and Ahmadiyya traditions, which were, in turn, influenced by centuries of practice among Hindu neighbours and family, both in India and in the Caribbean—in a sense, a kind of built-in ‘outernationalism’, Gilroy might say. This might indeed be considered an example of the diasporic hybridities and interculturation to which Gilroy points, but as Gilroy’s Black Atlantic also contains, there must be in any model of a Muslim Atlantic tension stimulated by debates that call for (certain expressions of) uniformity that seek to promote (certain expressions of) ‘insiderism’. Thus, imagined mutual exclusivities between Afro-Caribbean Muslims and Indo-Caribbean Muslims persist, as do debates among Caribbean Muslims in general about which school of thought and its beliefs and practices is authentic and legitimate.

The long-entrenched epistemological distinction between Afro- Caribbean Muslims and Indo-Caribbean Muslims refracts in contested and negotiated ways that reflect two important and interlinked dimensions: their relation to their respective social and cultural pasts, and their contemporary relations with each other in relation to the Caribbean states in which they reside. I have written about this in detail elsewhere (see, for example, Khan 1995, 1997, 2004, 2012), so for my purposes here I will simply reiterate that the ethno-national boundaries that designate ‘India’ and ‘Africa’ loom large in regional understandings of how Islam is defined according to its practitioners’ genealogical tracing back to their respective homelands. India symbolises one kind of Islamic authenticity, based on Indo-Caribbean hagiography about the abiding efforts of early generations of Muslim Indian indentured immigrant labourers on sugar plantations to keep their religious knowledge and traditions alive under the duress of want and discrimination.

Africa symbolises another kind of Islamic authenticity, based on Afro-Caribbean valorisation of forms of consciousness and personhood – identity – striven to be asserted through the abiding efforts of enslaved Africans on sugar plantations to keep their forms of knowledge and traditions alive under their own duress of want and discrimination. Arabia symbolises yet a third kind of Islamic authenticity, based on the interpretation by some Afro- and Indo-Caribbean Muslims as being shorn of the bidaa, or, in popular understanding, illegitimate innovations that the cultures of origin lands can foster and which may permeate Islamic beliefs and practices. In this sense, for some, Arabia is transcendent, projecting a purified, and thus proper Islam. Each of these geographical locations— India, Africa, Arabia—plays a role in the imaginaries of Muslims about how to best (most correctly) practice their religion in terms of particular school of thought, customary traditions, and worldview. These cultural- geographic divisions especially reinforce Afro- and Indo-Caribbean ideas about ethno-racial exclusivity and immutability in their service to the post- independence political cultures of nation-states, which in this region historically have capitalised on competing constituencies (voting blocs) of Afro and Indo, represented by putatively inevitable differences of cultural constitutions, sensibilities, values, and points of view—importantly, including religion—and rewarded with resources and opportunities geared to meeting those allegedly distinct needs. All of these challenges remind us why categorical distinctions take special effort, and why, even in diaspora, where presumably everything is breaking up into flexible, hybrid rearrangements, some orthodoxies, scholarly as well as religious, remain. Compounding these ideologies of race and nation (‘black’/‘brown’/’white’; Africa/India) is another key factor in striving toward realising a Muslim Atlantic. It is that of Islam’s elusiveness in its earliest New World diaspora: the debates about the nature of its survival over time among African Muslims and thus its identification as being recognisably ‘Islam’.

“Compounding these ideologies of race and nation (‘black’/‘brown’/’white’; Africa/India) is another key factor in striving toward realising a Muslim Atlantic. It is that of Islam’s elusiveness in its earliest New World diaspora: the debates about the nature of its survival over time among African Muslims and thus its identification as being recognisably ‘Islam’. “As I noted above, most scholars agree that throughout the Americas, Islamic beliefs and practices became absorbed into other, more populous religious traditions, gradually fading from ‘collective consciousness.’ As Diouf sees it, historians Brinsely Samaroo and Carl Campbell have argued that by the mid-nineteenth century a lively and effective African Muslim presence in the Caribbean had ebbed (Samaroo 1988; Campbell 1974). As Diouf sees it, in ‘Haiti, Brazil, Jamaica, and Trinidad, the Muslims and Islam were integrated into the religious life of the black population, just as any other African religions were. They were not accorded a special status but were not forgotten either; they just became another component of the religious and social world.’ (Diouf 2013: 277; see also Gomez 2005). Islam’s ‘traces’ were manifest in, for example, the representation of the ancestral and spirit worlds, and also materialised into paraphernalia that had ritual and other sacred significance. Historian Joaõ José Reis writes that after Brazil’s abolition of slavery in 1888, ‘formerly enslaved Muslims could still be found as isolated practitioners of their faith’ and that some of these Muslims ‘became well known makers of amulets’ (ritual objects that offer protection for the owner through otherworldly means), although this craft reflected ‘a very unorthodox Muslim way of life’. Reis’s perspective may have been reinforced by his awareness of the influence that amulets have today on the occult in Brazil (Reis 2001: 308). The main point here is that according to the accepted scholarship, the possibilities for Islam’s Atlantic world presence range from eventually non-existent to eventually simply hints of itself.

Vast geographical expanses, extensive passage of time, great cultural heterogeneity, and religious viability characterise the flow of Muslims and Islam to the Americas. Islam’s ‘whole’, its substance and its symbolism, is greater than the sum of its parts; its history, heterogeneity, geographical range, and the apprehensive imagery long associated with it from the Western gaze transcend Muslim individuals and communities of practitioners. This gestalt, or whole that exceeds the sum of its parts, helps put into perspective what realising a ‘Muslim Atlantic’ would entail, and mean. To remain within Gilroy’s vision, this gestalt must never project uniformity or impermeability yet it must remain empirically evident; it must honor the transness of diaspora yet not lose sight of regional specificity; it must be decisive about what recognition of Islam’s various ‘parts’ signifies (schools of thought, debates about practice, genealogies) while also giving those parts equal weight, at least as far as the particular historical and socio-cultural contexts will allow. Heterogeneous populations of African Muslims in the Americas have made for diverse ways of being Muslim even while all may subscribe to certain common denominators, typically taken from the Qur’an and the Hadith, by which they define and interpret Islam (Asad 1996; Leonard 2003).

“To remain within Gilroy’s vision, this gestalt must never project uniformity or impermeability yet it must remain empirically evident; it must honor the transness of diaspora yet not lose sight of regional specificity;…”Thus, the difficulty of drawing precise lines around our categories renders these issues vexed at the start. Gilroy’s revisionist objective was to envision a geographic and conceptual space that could negate nation-state based cultural nationalism and its bigotries and instead emphasise exchange and inclusivity. Nationalist paradigms are less emphatic for Muslims in Caribbean diasporas because there is no dominant narrative of entrenched Islamic history in this region. The region’s first century’s free Muslim seamen and other labourers, including enslaved Muslims, greatly diffused over its five-century history in the Americas, and the Islam of present-day Caribbean societies is associated either with Indo-Caribbean Muslims or Afro-Caribbean Muslim converts, or ‘returnees’. That said, all brought their Islam with them on transport ships headed across the Atlantic Ocean. Equally applicable to both groups is historian Peter Linebaugh’s comment that ships were ‘perhaps the most important conduit of Pan-African communication before the appearance of the long-playing record’(Linebaugh 1982:119). Dilution over diasporic time and space; cultural tropes that emphasise passage through uncertain borders across water rather than the often more visible borders across land; the governmentality of Euro-colonialism in the Caribbean, whose societies were defined by a dominant mode of production dedicated to a single commodity and a shared heritage of that commodity – plantation-based sugar and its byproducts. All of these compete with the idea of ‘nation’ and exclusive, entrenched national identities linked to it. This is not at all to say that nationalism does not exist in the Atlantic world. Far from it. But it is to suggest a generative tension among ideas about fluid and putatively firm identities that are empirically evident, as Gilroy pointed out more than a quarter century ago, and fluid and putatively firm identities that are ambiguous and not easy to pin down. These tensions are also a sound foundation for theory building from more hypothetical processes: in Gilroy’s conceptualisation, the ‘reflexive cultures and consciousness’ of indigenous Amerindians, Europeans, Africans, and Asians were never ‘sealed off hermetically’ from one another (Gilroy 1993: 2); rather, he explains, they were, and remain, lived daily in direct contact.

But, again, it is the nature of that contact that is up for debate, not least among scholars trying to capture, or recapture, what the Atlantic constitutes as an object of study. So let me consider, first, what we might think of as the divergence perspective on the relationship between New World Africans and Islam, which is a more contentious relationship, given what I have said above about the losses and uncertainties of historical Islam in the Atlantic world, than the one perceived between Indians and Islam. Then I will consider what we might think of as a convergence perspective on the relationship between Islam and the ‘intermixture of ideas’ (Gilroy 1993: ix), Gilroy describes as both historical and contemporary, African and Indian, that both flow through and create – realise – a Muslim Atlantic space. Gilroy’s focus is on Atlantic popular culture – notably music, luminaries of literature and philosophy, and the forms of cultural production that music and great thinkers generate. With different foci, the Muslim Atlantic also might be able to transcend or cross the ideological divides of exclusivity, immutability, purity, and ‘cultural insiderism’.

Although it is not a key word in Gilroy’s analysis, the concept of ‘creolisation’ is at the heart of his discussions of hybridity and intermixture. As employed by Atlantic world scholars, creolisation refers to the encounter between two or more cultures or cultural traditions (religious belief and practice, kinship organisation, aesthetic style, cuisine styles, and so on) and the mutual transformation each undergoes in relation to the other.

“Creolisation does not represent even exchanges but, instead, typically contentious engagements that occur within the context of unequal relations of power, in which certain cultures or cultural traditions will predominate and be socially valorised accordingly.”Creolisation does not represent even exchanges but, instead, typically contentious engagements that occur within the context of unequal relations of power, in which certain cultures or cultural traditions will predominate and be socially valorised accordingly. In arguing for the impact that Islam made among diasporic Africans in the New World, if not its tenacity, Diouf contends that African Muslims ‘did not participate in the creolisation process that commingled components of diverse African cultures and faiths with that of the slaveholders. By their dress, diet, names, rituals, schools, and imported religious items and books’, Diouf argues, ‘they clearly indicated that they intended to remain who they had been in Africa – be it emir, teacher, marabout, alfa, charno, imam, or simply believer … they shaped their response to enslavement, defining how the Muslims lived it and reacted to it. The people they had been in Africa determined the people they were in the Americas.’ (Diouf 2013: 282). She quite rightly recognises that the Euro-colonial Caribbean plantocracy’s view that African Muslims were superior to African non-Muslims was a racist view; still, African Muslims ‘seem to have distinguished themselves’, being ‘promoted and trusted in a particular way’ by that same plantocracy (Diouf 2013: 135-136). Standing out in this particular way may be another indication that African Muslims withstood creolisation, which Diouf perhaps sees in metaphoric terms as a kind of cultural homogenising.

It is true that the archival record shows that many African Muslims in the Atlantic world, free and enslaved, made conscious efforts to maintain their religious worldviews, and also that the plantocracies were aware that some Africans in their midst were Muslim, based on the regions from which they were captured and other such indicators as Diouf notes. But this divergence perspective raises a few questions. For one, most scholars would agree that all Africans in the diaspora arguably tried to maintain their religious traditions, and that all of these religious traditions have had more or less residual effects over the generations.

The question is why would Islam be more impervious to the forces of creolisation than other religious traditions, especially given that scholars, some quoted above, have written about the fusion of Islamic and non- Islamic beliefs and practices, fusions that absorbed Islam into a religio-cultural matrix in which it was frequently overshadowed.

“The question is why would Islam be more impervious to the forces of creolisation than other religious traditions, especially given that scholars, some quoted above, have written about the fusion of Islamic and non- Islamic beliefs and practices, fusions that absorbed Islam into a religio-cultural matrix in which it was frequently overshadowed.”Another issue is that as scholars understand it, creolisation is not necessarily a conscious process or purposeful endeavour. Cultural transformation within unequal relations of power happen whether or not people want it to, and whether or not people are aware of it while it is happening. There were indeed many instances and expressions of refusal of imposed and dominant epistemologies, slave revolts being a prime example, but these, as such, would typically not be categorised as exemplifying or contradicting ‘creolisation’. And because creolisation is basically a way of theorising the workings of culture, no one who lives within that culture can opt out; intentions to remain outside of, distant from, or impervious to can be successful, but they are not the norms of lived experience; they must have catalysts that motivate within particular moments. Certainly, how people define their personhood in their original homeland, including in the parts of Africa that would end up in New World diasporas, informed, but did not determine, the people they would continue to become in the Americas. That said, like Gilroy, Diouf is making an important argument about power and agency, and the creativity that emerges from acts of self-assertion and self-realisation. Again, the challenge for a ‘Muslim Atlantic’ is to interpret agentive acts and forms of consciousness in ways that acknowledge all forms of agency – including claims to mutual exclusivity, purity, and immutability (to which no religion is a stranger) – while drawing together common denominators that can tell a new story.

Just who gets to tell that story is also a contentious issue. One important example of drawing explanatory templates from Islam and the question of who espouses them is the dialogue between historian Sultana Afroz and anthropologist Kenneth Bilby. Afroz bases her argument on a reasonable premise: that researching Caribbean history should not rely solely on the records of European slave traders and ruling authorities; that the work of African scholars based on African sources must also be part of historiographical narratives. This raises an important point about sources as situated forms of knowledge, and why and when certain ways of knowing may be more subject to elision than others. But Afroz holds steady a model of clearly distinguishable Caribbean (Afro-)Muslim communities, whose dedication to Islamic values and practices, she contends, informed and inspired the resistance to oppression among all enslaved Africans as well as among Maroons: communities of escaped enslaved Africans who were a vibrant and politically important presence in many slave plantation societies in the Atlantic world, notably including, for example, Jamaica, Brazil, and Surinam. But even if we dispense with the idea of obvious and cohesive communities, Afroz’s claims merit at least further investigation. Perhaps not as many as ‘numerous’, but certainly some leaders among enslaved Africans could have been ‘crypto-Muslims’ – marabouts or imams (Afroz 2003: 214; Diouf 2013). Moreover, it is a useful question to ask what the implications might be of calling an uprising a ‘slave rebellion’ versus a ‘jihad’ for the way we understand both, and thus the ways that historiographical narratives about the Americas are produced. At the same time, Afroz draws a clear line around Islam in the Atlantic world with her look askance at the attribution to obeah of the heroic efforts and miraculous achievements of elslaved freedom fighters, and her interpretation of African traditions of making offerings to the ancestors as in fact being Islam’s voluntary giving of alms. Yet as I have written elsewhere (Khan 2012), the story of the inaugural moment of the Haitian Revolution is its catalysis by Haitian national hero (and perhaps apocryphal figure) ‘Boukman’, who was both an houngan (Vodou priest) and imam. This memorialisation captures the ambiguity of a Muslim identity; there is no necessary either/or choice that can be made, unless as an ideological imposition. The messiness of lived experience and of commemoration typically belies categorical summaries.

In his critique of Afroz, Bilby describes her work on the Islamic heritage of maroons in Jamaica as ‘feats of imagination’(Bilby 2006:53). His central charge is that Afroz lacks evidence to support her claims that Maroon cultural heritage derives from Islam. Bilby objects to attempts, including by academics, ‘to appropriate the glory of the Maroon epic’(Bilby 2006: 53). He is also disturbed by work that gives primacy to interpretations of Maroon history that conflict with Maroons’ own understandings, which he sees as resulting in ‘severing the Maroons of today from their own past’ (Bilby 2006: 53). But in addition to the Islam of West and Central Africa, Maroons’ past may have involved Christianity, as well, despite Bilby’s skepticism that Christianity, or Islam, had much influence on Maroon religious tradition (Bilby 2006: 433, fn 54). This may forever be unknowable as a certainty, but creolisation processes among enslaved Africans began even before passage across the Atlantic (see, for example, Sidney Mintz and Richard Price 1992). Bilby is right that all historiographies must be considered when one is attempting to know a community or a people. Taking seriously the point of view of one’s interlocutors is an ethical decision a researcher makes about their relationship with those interlocutors. But it establishes neither fact nor truth. Afroz takes the perspective of the whole: Islam, undifferentiated, yet ‘invincible’, as her essay’s title ‘Invisible Yet Invincible’ contends. Bilby all but discounts Islam’s influences in Maroon life, which he seems to suggest jeopardise Maroon understanding of their history and sense of personhood. Both positions assume the primary importance of facts: Afroz’s facts are based on a particular take on religion and Bilby’s are based on a particular take on history. But these authors’ positions also promote their respective dedication to what could also be read as a kind of intellectual purification, where the lived experiences of ambiguity overlap, and changing imaginaries (creolisation?) take second place to ideal(ised) representations.

In a similar vein as Afroz’s doubt about the connections between Islam and obeah, Diouf draws a distinction between Islam and African religious traditions vis-à-vis religious syncretism. She argues that ‘unorthodoxy and tolerance of foreign elements…are characteristic of the successful African religions that are still alive today. They became creolised borrowing features from a diversity of religions and synthetising them’. By contrast, although ‘in Africa, Islam and traditional religions are not exclusive’, Diouf notes, ‘there are limits to what Islam can absorb’. Syncretism is not acceptable. For Diouf, creolisation comes through religious conversion, which, she says, was not the case with Islam’s survival in the Americas; instead, Islam’s survival was ‘due to the continuous arrival of Africans – including the recaptives and the indentured labourers after the abolition of slavery in the British and French islands’ (Diouf 2013: 256-257). Such survival of ‘Islamic traits’ was either recognisable by the adherents of African religious traditions, who, for example, ‘make direct references to Allah, the Muslims, or Arabic’, according to Diouf, or although Islamic origins may have been forgotten ‘they are present and almost as visible’ (Diouf 2013: 260). This visibility, however, demonstrates that ‘there was no fusion [creolisation] but rather co-existence, juxtaposition, or symbiosis’(Diouf 2013: 260).

Ultimately, the tension lies between Africans’ diversity and African Muslims’ cohesion, given that ‘whatever their origin, [Muslims] all shared a number of characteristics that made them stand out,’ (Diouf 2013: 101) writes Diouf. For example, they were ‘frugal, ascetic people’; they led a ‘discreet and devout lifestyle’; they all shared ‘a language, a writing system, a set of values, and habits’ that transcended ethnic group, caste, and region; they shared a similar education (Diouf 2013: 101, 99-100, 70). Enslaved African Muslims purportedly also disproportionately occupied high status plantation jobs, despite their lack of familiarity with ‘the rules and regulations of the plantation world’ and the language spoken in it. Thus, Diouf surmises, they must have had ‘particular qualities that enabled them to climb quickly up the social ladder of the plantations’(Diouf 2013: 137). This is while Hisham Aidi and Manning Marable argue that in the US, for example, enslaved African Muslims not only were differentiated from non-Muslim Africans by colonisers, they also ‘distanced themselves from their non-Muslim counterparts … often eagerly claim[ing] Moorish, Arab, or Berber origins’, revealing an ‘air of superiority’ on their part (Aidi and Marable 2009: 6).

“This is while Hisham Aidi and Manning Marable argue that in the US, for example, enslaved African Muslims not only were differentiated from non-Muslim Africans by colonisers, they also ‘distanced themselves from their non-Muslim counterparts … often eagerly claim[ing] Moorish, Arab, or Berber origins’, revealing an ‘air of superiority’ on their part (Aidi and Marable 2009: 6).”

Diouf seems to be arguing that in Africa, Islam and non-Islamic religious traditions were receptive to one another, but in the Atlantic world Islam exercised influence without itself being influenced. Observable traits and special dispositions notwithstanding, however, the key to African Muslims’ fortitude was that ‘their minds were free’. They may have had mortal masters but they were, existentially, servants of Allah (Diouf 2013: 283). In other words, in the Atlantic world, and the Americas more generally, Muslims’ consciousness was impermeable: they did not succumb to what others, such as Bob Marley in ‘Redemption Song’, call ‘mental slavery’. This sense of free minds, of consciousness, is a different, although not contradictory, kind of awareness than is the ‘hemispheric if not global’ forms of consciousness that Gilroy envisions. This is perhaps because Gilroy starts with populations already vastly diverse, as he well recognises, who may be grouped under the rubric ‘black’ in their formation, through cultural production, of a ‘Black Atlantic’, which is impossible, in Gilroy’s formulation, to capture within such boundaries as ‘nation’ and ‘race.’ Diouf and scholars who make similar arguments start with a delimited entity, Islam/Muslim, which, as I noted earlier, can act as a ‘nation’ even though it is not one in the conventional sense of the word. The key question is: what are the ideological stakes involved in arguing for or against the fluidity of boundaries, group cohesiveness, and ‘cultural insiderism’?

For Gilroy and his colleagues, the revisionist agenda is, in part, a struggle against (racial) delimitation and containment. For Diouf and her colleagues, the revisionist agenda is, in part, a struggle against (religious) denial and elision. Yet, arguably, both demand a kind of recognition, a correction of political-sociological blind spots and their consequences. Given this shared goal, can a ‘Muslim Atlantic’ call upon what we might term a convergence perspective that emphasises the ways that Muslims’ experiences and representation in the Americas differ from those we are more often accustomed to hearing from Europe and North America? In other words, can a ‘Muslim Atlantic’ deliver theoretical paths to the kinds of openness, fairness, inclusivity, and valorisation of the inter rather than intra; that is, unity without uniformity? Can there be such a thing as a nation without borders, and is a ‘Muslim Atlantic’ such an entity—an ummah that is not simply ‘global’ but reimagines ‘nations’ as another kind of entity, as extraneous to geo-political states?

Given the tenacity of boundaries and distinctions that evoke group separateness and racial-cultural exclusivity, envisioning a convergence perspective that can produce models of group cohesiveness and racial- cultural inclusivity also takes effort. The challenge is to create a category of lived experience that maintains the openness, anticipation, and fluidity that lived experience is made of. This may take further research into the syncretism and creolisation that historically, culturally, and socially have tied Islam to Atlantic religious traditions for half a millennium. But perhaps even more crucially, it will take a shift in perspective about what we already know. Reading Diouf, we know that in Africa, India, and the Atlantic world there were, and remain, contact zones in which Islamic, non-Islamic, and pre-Islamic beliefs and practices intermesh, such as shared or converged deities, rites, lexicons, and ritual objects (Diouf 2013: 260), or as fusions within individuals themselves, as the narratives about the Haitian Revolution’s most famous figures of resistance, Makandal and Boukman, aver.

We can think of these processes and people as beyond the bounds of creolisation or as consummate examples of it. And if we think in terms of creolisation, we can envision such transformations as producing new forms of exclusive ownership of culture and identity, or always-in-motion, communally shared cultures and identities. We can work to imagine what kinds of shared differences emerge from interactive dialogue and mutual awareness, or, by contrast, see those differences as inimical. There is not much in the world that is self-evident. From various subject positions and perceived stakes, we work to make things seem that way.

“Muslims come in many forms – recognisable, contested, and unrecognised. Thus it stands to reason that we approach Islam as multilayered, receptive, flexible, as always in process even while practitioners and observers may view Islam as more stable. This is one example of the unceasing tension between phenomenological and ideological optics.”

Muslims come in many forms – recognisable, contested, and unrecognised. Thus it stands to reason that we approach Islam as multilayered, receptive, flexible, as always in process even while practitioners and observers may view Islam as more stable. This is one example of the unceasing tension between phenomenological and ideological optics.

In the spirit of Gilroy’s emphasis on popular culture, notably music, as illustrative examples of the reality and utility of a ‘Black Atlantic’ reading of the Atlantic world, and corrective to the misdirection present in the ideas of ‘nation’ and ‘nationalism’, perhaps we can end on a note taking inspiration from a classic, top-selling song by American Funk music band Funkadelic, with whom Gilroy is surely acquainted, whose members included the important musician and record producer George Clinton. The song, ‘One Nation Under A Groove’ (1978; Junie Morrison, George Clinton, and Garry Shider), contains a political message that suggests a ‘nation’ whose groove makes it open and all-inclusive, a meta-nation, one might say.

As a model for the Muslim Atlantic, one ummah under a groove seems a logical, and laudable counterpart to strive for.

Aisha Khan is a member of the Anthropology department and is affiliated with the Center for Latin American and Caribbean Studies and the Hagop Kevorkian Center for Near Eastern Studies at New York University. She has conducted research in Honduras, Trinidad, Guyana, and Haiti, and has published widely on South Asian and African diasporas, race, religion, colonialism, and creolization. Her published works include the monographs Callaloo Nation (2004) and Troubled Inheritance(forthcoming); the edited volume, Islam and the Americas (2015), and the co-edited volumes Empirical Futures (2009) and Women Anthropologists (1988, winner, ChoiceOutstanding Academic Book Award).

*Cover image credit: Fatima Jamadar and Hurst.

Bibliography

Bilby, Kenneth, 2006. True-born Maroons. Kingston, Jamaica: Ian Randle.

Gilsenan, Michael, 1982. Recognizing Islam: An Anthropologist’s Introduction. London: Croom Helm.

Khan, Aisha, 2012. ‘Islam, Vodou, and the Making of the Afro-Atlantic,’

Nieuwe West Indian Gids/New West Indian Guide 86 (1-2): 29-54.

Linebaugh, Peter, 1982, ‘‘All the Atlantic Mountains Shook’,’ Labour/Le Travailleur 10: 87-121.

Ouzgane, Lahoucine, 2006. Islamic Masculinities. London: Zed.

Samaroo, Brinsley 1988. Early African and East Indian Muslims in Trinidad and Tobago. Paper presented at Conference on Indo-Caribbean History and Culture, May 9-11, Centre for Caribbean Studies, University of Warwick, Coventry, England.