The Al-Qaeda boogeyman in Bosnia

”10.000 mujahedeen in Bosnia and Herzegovina ready for a new Jihad.”

This is how the headline of an article read in a leading Bosnian Serb newspaper in January 2019. It claimed that Bosniak Muslims were organizing online, ready and waiting to take up arms and fight a holy war against Orthodox Christian Serbs. The “mujahedeen” the article refers to was a small, undisciplined, rag-tag unit made up of Arab fighters who fought alongside Bosnian government forces during the 1992-1995 war. Their military role was marginal, and, under American pressure, a majority were expelled after the war. Some even ended up in Guantanamo. A quarter of a century later, their war-time role has become bloated to mythical proportions by nationalist Serb and Croat journalists, academics, and politicians. So much so that hardly an article on Salafi Islam in the Balkans passes without some reference to the mujahedeen.

I noticed a more sinister use of the mujahedeen’s war-time presence to, retroactively, depict Bosniak Muslims as ‘Islamic radicals’ and the 1992-1995 war as ‘war on terror.’

Here is how it is framed.

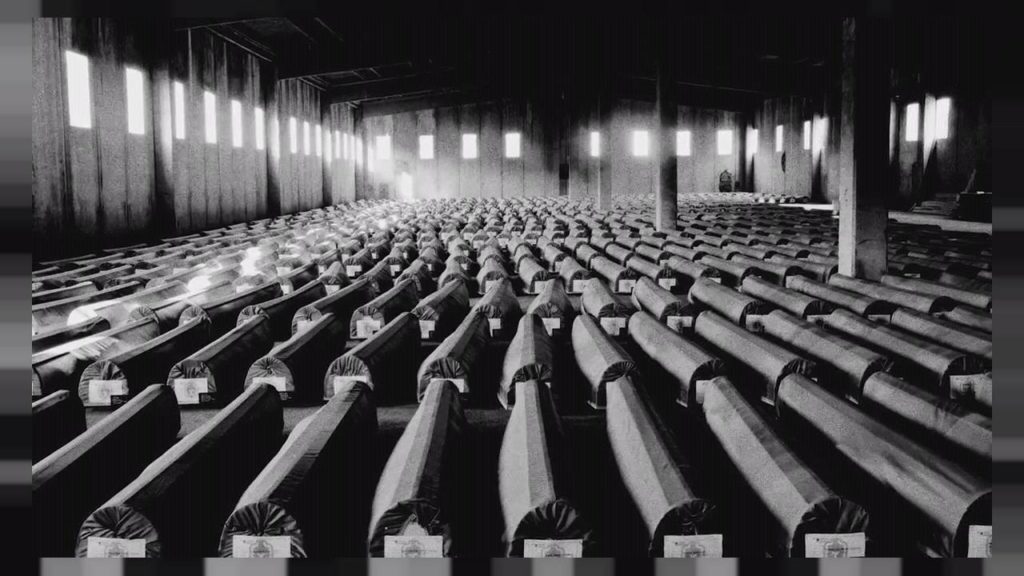

“I noticed a more sinister use of the mujahedeen’s war-time presence to, retroactively, depict Bosniak Muslims as ‘Islamic radicals’ and the 1992-1995 war as ‘war on terror.’“This 11th July 2020, Bosniak Muslims will commemorate the 25th anniversary of genocide in an ever-unfriendlier international environment. Back in the 1990s Bosniak Muslims were portrayed in Western media as the defenders of a multi-ethnic secular state against marauding Serb and Croat genocidaires intent on wiping out their white Slavic Muslim neighbors. After all, Serbs had committed the first genocide in Europe after the Holocaust. Such an image of them lingered for years, that is, until the September 11, 2001 attacks in America.

“Determined to brush off their image as genocidaires, nationalistic Serb and Croat journalists, academics and politicians realized that they too could bandwagon with the rest of the world in their fight against ‘Islamic radicalism’ and win much-needed friends in Europe and the US.”

Following 9/11 and the ensuing anti-Muslim hysteria worldwide, the media, academia and think tanks fixated their attention to the new enemy – ‘Muslim extremists’. American President George W. Bush gave the world an ultimatum – ‘You are either with us, or you are with the terrorists.’ The key words we heard on television back then were ‘jihad’, ‘terrorism’, ‘Islam’, ‘madrasa’, ‘mujahedeen’, ‘Taliban’ and ‘Al-Qaeda.’ War on terror became a morality tale, the good versus the bad. Any state, from the Philippines to Russia, that had issues with its Muslim minority or separatist movement, applied the ‘war on terror’ argument to eschew unwanted criticism of human rights violations or excessive use of force.

The Balkans were no exception.

Determined to brush off their image as genocidaires, nationalistic Serb and Croat journalists, academics and politicians realized that they too could bandwagon with the rest of the world in their fight against ‘Islamic radicalism’ and win much-needed friends in Europe and the US. The most plausible way of doing so was by portraying their Bosniak Muslims neighbors as ‘white Al-Qaeda’ and thereby casting suspicion on the white Slavic Muslims as religious Islamic fanatics who, by virtue of their skin color, could easily blend in into the European public sphere. The presence of the mujahedeen during the war, who by their looks remind the average media consumer of Al-Qaeda and ISIL, became conclusive evidence of how ‘Islamic radicals’ had fought alongside Bosniak Muslims.

Genocide as ‘war on terror’

In a year-long research I conducted titled Constructing the Internal Enemy: A Discourse Analysis of the Representation of Islam and Muslims in Bosnian Media, I concluded that Bosnian Serb and Croat media displayed a pervasive tendency to focus on the allegedly threatening nature of Bosniak Muslims, depicting them as susceptible to religious radicalism. This connection was established through chains of association with international terrorist groups and a range of narrative elements such as the war-time presence of foreign Islamic fighters. Such threats were depicted as both realistic, in the sense that they may cause physical harm to Balkan Christians, as well as symbolic. The most common association made between Bosniak Muslims and terrorism is of them being an extension of existing global terrorist networks, specifically ISIL and Al Qaeda. Many articles focused on Bosnian ISIL fighters returning from Syria and Iraq and the threat they pose to the country and the region.

“These newspapers systematically chose international events that fit their negative interpretations of Islam and stereotypes of Muslims, while the structures of their articles attempted to show a spill-over effect of Middle Eastern conflicts onto the Balkans.“

These newspapers systematically chose international events that fit their negative interpretations of Islam and stereotypes of Muslims, while the structures of their articles attempted to show a spill-over effect of Middle Eastern conflicts onto the Balkans. I came across headlines in Bosnian Serb and Bosnian Croat media such as “They came to Bosnia after fighting in Afghanistan. Then they waged jihad around the world,’’ “These are the leaders of Balkan jihadis’’ and “War-time mujahedeen fighters spread fear throughout Bosnia’’ and “Osama bin Laden prayed in Sarajevo. The attacks against America were planned in Bosnia!’’

Most of these unsubstantiated and sometimes blatantly fictitious articles, in some way or other, alluded to the war-time presence of foreign Islamic fighters, or claimed that Al-Qaeda had fighters or even bases in Bosnia during the war. Interestingly enough, the presence of Russian and Greek volunteers fighting alongside Bosnian Serb forces was completely neglected.

Such a narrative cunningly switched the plot from ‘Bosnian Serbs massacred Muslims’ to ‘Bosnian Serbs defended themselves against Islamic radicals.’ In tandem with switching the narrative, these articles vehemently denied that ‘their side’ ever committed war crimes. Conveniently, they applied more polished and refined strategies of scientific rationalization (‘killing 8.000 Muslims is not genocide’), relativization (‘all sides committed war crimes’) and recontextualization (‘we only defended ourselves against extremists’).

“Such a narrative cunningly switched the plot from ‘Bosnian Serbs massacred Muslims’ to ‘Bosnian Serbs defended themselves against Islamic radicals.’“

A similar conclusion was deducted by Karmen Erjavec and Zala Volčić in their excellent study Croatian journalists’ narratives on Croatian war crimes in Bosnia-Herzegovina. The two Balkan scholars found out that the proposition ‘We had to fight against Islamic terrorism’ was adopted by more than half of all the interviewed journalists. Aside from relativizing war-crimes, these Croatian journalists went one step further and appropriated US President George W. Bush’s ‘war on terrorism’ discourse to their own socio-historical context. Thus, by drawing an analogy between Croatia’s involvement in the 1992-1995 war against Bosniak Muslims and America’s post-2001 wars on terrorism, they retroactively legitimized and justified massacres of Bosniak Muslim civilians. Accordingly, in their recycled back-projection of world events, Bosnia and Herzegovina becomes ‘the Balkan hotbed of terrorism’ while their war against Bosniak Muslims becomes the ‘war on terror.’ In their interviews, Croatian journalists heavily applied the American counter-terror vocabulary and drew analogies with the US invasion of Iraq such as ‘killing Bosniak civilians was a necessary evil just like … what’s going on in Iraq today’ and ‘I think that Croatia had to fight against Islamic terrorists like America or the West do…’

From their answers, the binary opposition of ‘we/Croats/good’ and ‘they/Muslims/bad’ was more than obvious.

In another study titled ‘War on terrorism’ as a discursive battleground: Serbian recontextualization of G.W. Bush’s discourse, Karmen Erjavec and Zala Volčić again show similar recycling and appropriation of the ‘war on terror’ narrative to justify Serbian crimes against Muslims. Here it is worth noting that even though Serbia had troubled relations with the United States (the US-led NATO campaign bombed Serbia in 1999), it nevertheless found Washington’s counter-terrorism discourse useful and applicable to Bosnia. In their interviews with Erjavec and Volčić, Serbian intellectuals justified the war time killings of Bosniak Muslims as a necessity in combatting terrorism. One interviewed intellectual said ‘It is very tragic what has happened in the former Yugoslav republic…but one needs to understand that we have had our 9/11 for the past ten years here’ while another said ‘We recognized the danger of fundamentalism and terrorism in the 1980s…we knew that we needed to defend ourselves in Bosnia and Kosovo’ while a third intellectual said ‘Yes, I tell you…a crusade against Muslim terrorists is the only real way to go and win.’ Perhaps the most éclatante example of establishing a direct correlation between 9/11 and the Bosnian war was seen in the following answer coming from a Serbian intellectual: ‘It seems to me that the September 11 attacks showed a clear dichotomy of a victim and a perpetrator. This also works like that in the Balkans… We, the Christians, are the victims and the Muslims are an evil… and we need to explain the situation in this region to the West through some examples of the connections between Bosnian Muslims and Islamic fundamentalists.’

Switching the victim-perpetrator narrative

It is worth noting that in such answers, Bosniak Muslims are referred to as a unified, homogeneous mass with a common subjectivity that is at odds with the rest of Christian Europe. This shared commonality between Serbian and Croatian journalists and academics and the American ‘war on terror’ is often defined in light of sharing a common threat perception. Bosniak Muslims are reframed as a present-day security risk and back projected as having been an equal risk in the 1990s. By reducing them to ‘Islamic terrorists’, Bosniak Muslims are depicted as the violent and irrational ‘other.’ Such a discourse becomes self-righteous, simplistic and moralizing. Thus, military action against Muslims is presented as the only means of solving the problem.

“Once seen as a paranoid nationalistic discourse employed by Serb war criminals, the depiction of Bosniak Muslims as Islamic fanatics has been gaining momentum and becoming mainstream.“

Once seen as a paranoid nationalistic discourse employed by Serb war criminals, the depiction of Bosniak Muslims as Islamic fanatics has been gaining momentum and becoming mainstream. Such a narrative was given a boost from Croatia’s then President Kolinda Grabar-Kitarovic who during a visit to Israel said that Bosnia was a security threat and a haven for “militant Islam.” France’s President Emmanuel Macron picked up the narrative and in an interview with the Economist last year called Bosnia and Herzegovina a “ticking time-bomb” and claimed that Europe’s biggest concern in the Balkans are the “jihadists” returning from Syria and Iraq.

“Serbian and Croatian nationalists found it useful to hide their irredentist aspirations towards Bosnia’s territory and their genocide of Muslim Bosniaks under the clout of fighting an insidious enemy.“To make matters worse for Bosniak Muslims, major European media outlets hooked onto the newly established narrative. In fact, over the past four to five years, France 24 produced a documentary titled Bosnia: Islamic state group prime recruitment hotbed in Europe, German state broadcaster DW produced Bosnia and Herzegovina: a gateway for IS?, American PBS produced Is Saudi-funded mosque in Sarajevo threat to Bosnia’s moderate Muslims? while the BBC produced Bosnia: Cradle of modern jihadism? On YouTube alone, each of these documentaries clocked up hundreds of thousands of views. In almost each and every one of them, the war-time presence of mujahedeen fighters was brought into direct correlation with Bosnian Salafism and ISIL.

Serbian and Croatian nationalists found it useful to hide their irredentist aspirations towards Bosnia’s territory and their genocide of Muslim Bosniaks under the clout of fighting an insidious enemy. Such an ideology drenched in defense against an alleged Islamic threat bent on waging jihad and subjugating Christians to Muslim rule becomes a major justification for genocide. Thus, the dehumanization of Muslims provides a moral justification for rooting them out in a hyperbolic fight of good versus evil.

In this new narrative, Bosniak Muslims become Al-Qaeda, Bosnia becomes the new Afghanistan, and the 1995 genocide becomes a pre-emptive counter terrorism operation.

Dr. Harun Karčić is a journalist and political analyst based in Sarajevo and a fellow at the Center for Advanced Studies. He specializes in post-communist Islam in the Balkans and the impact of foreign Islamic factors on Balkan Muslims. He tweets at @HarunKarcic.