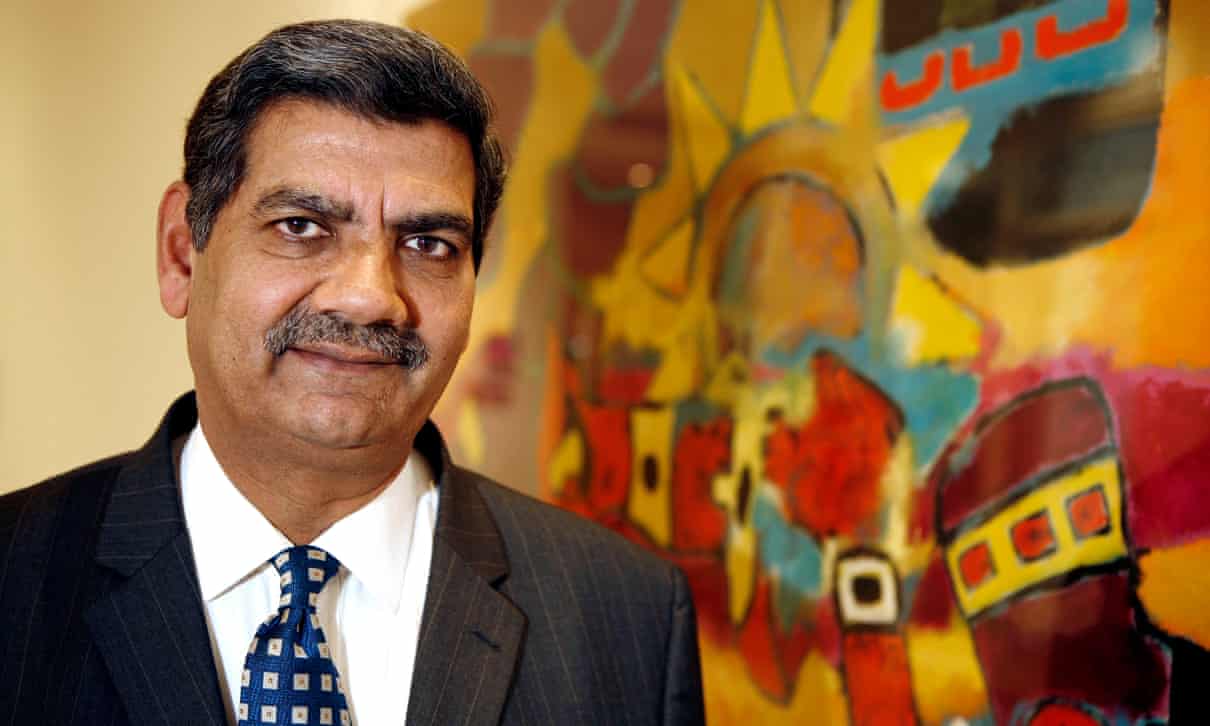

After Professor Muhammad Anwar, OBE, FRSA, passed away last month, Virinder S Kalra, head of the department of sociology at the University of Warwick, wrote that he was a “founding figure in the field of social policy” and that his books in the 70s, 80s and 90s were “landmark publications of their time.” He was right on both counts, but Anwar was also much, much more. For me personally, he was a valued mentor whose positive impact reached from Pakistan to Paris to Peterborough – and from Aberdeen to Ankara to America. He took me through some of my most formative years as a young, mixed-race academic, just after 9/11. When Maydan requested I write about him, its editor reminded me that tributes to such scholars are an important way in which to inform younger scholars about the work of leading names in the broader study of Muslims. And, as such, I was honoured to do so, because Professor Anwar really was significant and important – and here we are.

Public Framing Of Ethnic Minorities

I remember the very first time I met Professor Anwar in his office at the University of Warwick. I was completing my masters’ thesis at the time, and was in the midst of applying for doctoral programs at various universities. It would have been early 2001, and at the time, I didn’t have much of an idea about Warwick as a university. What was important to me was that there was this scholar in the UK who was taking PhD students and who was one of the top academics worldwide studying the subject that I wanted to research, which was European Muslim communities.

“In both the public and the academic world of the past four decades, Professor Anwar was one of the most significant voices regarding public and academic framing of ethnic and religious minorities in the UK and internationally.”

In both the public and the academic world of the past four decades, Professor Anwar was one of the most significant voices regarding public and academic framing of ethnic and religious minorities in the UK and internationally. Balancing between policy engagement and scholastic rigour, he ensured the mainstreaming of understanding the challenges faced by minorities when it came to political participation, the media and education. I didn’t yet fully appreciate the importance of his approach when I went to see him early in 2001. A few months later, however, that all changed because of 9/11.

It has been almost two decades since 9/11, such that today’s younger academics just starting out probably cannot even perceive of a pre-9/11 environment in academia or in the public arena. I began my doctoral studies literally days after 9/11 happened. Before that critical turning point for global Muslim life, my doctoral topic was perhaps of little interest to many outside the field – but post 9/11, the study of European diversity, Muslim communities, and Islam suddenly took on very prominent profiles indeed.

Tenaciously Non-Partisan Thinker

In retrospect, I was given a great opportunity by being able to study with and know Professor Anwar, not least of all because of his own career in the public arena. His policy and scholarly work at institutions like the Commission of Racial Equality (CRE), where he served as head of research, meant he understood the public sphere very well. When I became his doctoral student, I wasn’t aiming for a public profile at all – I wasn’t remotely interested, and didn’t think that was the direction towards which I was headed. But when you study these topics beginning your PhD just after 9/11, and completing it just before the 7th of July 2005 bombings in the UK, it’s somewhat unavoidable, I suppose. Professor Anwar, as a public intellectual, with deep, non-partisan expertise in his research areas, had a great deal of experience that, in retrospect, benefited me tremendously.

“Rather, Professor Anwar gave more weight to expertise than ideology. He was squarely within the ‘multiculturalist’ school, which comes out of liberal political theory, to be sure. But when he wrote, it was always rooted in evidence; primary research; statistics – and he didn’t try to force his view upon his students.”

Over the past two decades, I’ve engaged in the public arena through think tanks like Brookings, Carnegie, and the Royal Institute (RUSI), on issues of a great deal of controversy –European Muslim communities, Arab politics, Islam and the modern world. However, I’ve always made sure to remain non-partisan as I do so. Looking back on my time with Professor Anwar, I reckon that a significant reason why I was able to maintain such non-partisanship is because of his own work – he was tenaciously non-partisan, and was never identified with a particular political party or trend, even though he probably could have benefited greatly if he’d done so.

Rather, Professor Anwar gave more weight to expertise than ideology. He was squarely within the ‘multiculturalist’ school, which comes out of liberal political theory, to be sure. But when he wrote, it was always rooted in evidence; primary research; statistics – and he didn’t try to force his view upon his students. As I went on to teach my own students in my own academic career, I tried hard to remember that.

The Public Intellectual With Scholarly Humility

Professor Anwar’s decision to always be careful about what expertise he had or didn’t have came at a cost. For instance, Professor Anwar wasn’t an expert on Islam. Post 7/7, the field of ‘experts’ on Islam exploded – even more than post 9/11 – and frankly, Professor Anwar could have become even more prominent had he engaged on the public stage as another expert on Islam. This phenomenon of “experts” on Islam jockeying for attention in the media has only increased since the 7th of July attacks, but Professor Anwar never went in that direction. On the contrary, I remember very clearly on one occasion, the subject of Islam came up in my doctoral thesis – and rather than try to pontificate about religion in some way, he made a strong recommendation to contact a particular Egyptian shaykh and scholar that he knew and that he regarded as knowledgeable. Almost two decades later, that particular conversation stuck with me – particularly because of its substantive content, but also because of how increasingly rare this kind of scholarly humility and commitment has become.

“Professor Anwar could have become even more prominent had he engaged on the public stage as another expert on Islam. This phenomenon of ‘experts’ on Islam jockeying for attention in the media has only increased since the 7th of July attacks, but Professor Anwar never went in that direction.”

He did, on the other hand, know an incredible amount about Muslims. Professor Anwar was one of the most insightful academic figures examining the effects of anti-Muslim bigotry and Islamophobia. His contributions, though in many ways taken for granted today, were deeply controversial as he rose to more prominence in the public sphere. A pride of the British Pakistani community and a committed Muslim, Anwar was recognised widely in the mainstream as an independent, non-partisan expert for his contributions – which eventually led to his being made OBE in 2007.

When Anwar left the CRE, he went to Warwick University, becoming a full Professor. He’d been instrumental in the multi-disciplinary research centre in the social sciences and the humanities, entitled the ‘Centre for Research in Ethnic Relations’, serving at different times as its director and the head of its PhD program. Warwick University’s current vice-chancellor, Professor Stuart Croft, this week described Anwar’s appointment as “a great coup for the University of Warwick.” Anwar’s high standards were at least partially responsible for the Centre for Research in Ethnic Relations being funded by the Economic and Social Research Council to the tune of millions of pounds.

He was a crucial member of the Runnymede Trust’s Commission on the Future of Multi-Ethnic Britain, chaired by Lord Professor Bhikhu Parekh, and including notables like Professor Bob Hepple of Cambridge, Andrew Marr of the BBC, and Professor Tariq Modood of Bristol. Some two thirds of the commission’s recommendations were accepted by the UK government in 2000. A member of the BBC’s General Advisory Council, Anwar was widely recognised as independent and non-partisan, and at the same time, a deeply committed, organic scholar. Whether it meant authoring surveys for Operation Black Vote, or writing academic tomes about political participation of ethnic minorities, his purpose and approach were clear.

His Legacy, Students and All

As his work became more mainstream, Professor Anwar trained a generation of scholars internationally, as far afield as the United States and France, Egypt and Turkey. I wasn’t his only student – not by a long stretch. My own work was propelled onto the national scene immediately following graduation due to the 7th of July bombings, and my being asked to serve as deputy convenor of the UK government’s taskforce on radicalisation. But other students made incredibly important contributions as civil servants, as politicians and as academics. Some of them, like me, were interested in Muslim communities of the West; some were engaged in fighting discrimination against Black communities in the US or the UK; others became political activists or politicians.

“Professor Anwar was a deeply involved public intellectual beginning at a time when to be of Pakistani origins in public life was hardly easy. His work on the study of minorities stridently examined the gaps British societies had in empowering its ethnic and religious minorities and offered practical solutions.”

Professor Anwar was a deeply involved public intellectual beginning at a time when to be of Pakistani origins in public life was hardly easy. His work on the study of minorities stridently examined the gaps British societies had in empowering its ethnic and religious minorities and offered practical solutions. Anwar’s contributions continue to be standard references within the world of academia, and no less so because of its sustained relevance. As Kalra mentioned in his own obituary, “‘His Between Two Cultures (1976), Race and Politics (1986), British Pakistanis, Demographic, Social and economic position (1996) were landmark publications of their time.””The Black Lives Matter movement, the rise of white supremacy, the ongoing discussion of the role and place of Muslim Europeans – all of these topics and many more are deeply related to Anwar’s academic work. It’s important for all in contemporary Islamic studies to consider – Professor Anwar was clearly aware of the importance of power in the arenas he studied, and clearly many his students did as well. One of his PhD students was a descendant of the famous ‘Windrush generation’ – that group of nearly half a million Black people who moved from the Caribbean to the UK in the mid-twentieth century. She never lost that awareness, and even during her career in the British civil service, she publicly spoke up about her concerns as a Black Briton in twenty-first century.

I am not sure how much I can emphasise how important Professor Anwar’s pastoral or mentor role was for his students. As I drew closer to finishing my PhD, he was asking me quite regularly about what my plans were in order to move into academia full time and encouraging me to take steps accordingly. I knew of another former student whom he helped make the move from the civil service into academia years after he’d graduated from Professor Anwar’s program. On top of that, though, he also wasn’t going to let students progress if he didn’t think they were ready and I knew of one student like that who needed something of a push. Unlike many other academics, Professor Anwar had a deep concern for his students. His students also testify widely to his being a warm and gentle soul who took genuine interest in the well-being of those he mentored.

“The world of race relations and the study of minorities in the UK and Europe has changed dramatically over the last few decades, and not everyone has survived the change with their reputations intact. Anwar kept to genuine evidence based research, and was thus cited widely in the press as well as academia…”

The world of race relations and the study of minorities in the UK and Europe has changed dramatically over the last few decades, and not everyone has survived the change with their reputations intact. Anwar kept to genuine evidence based research, and was thus cited widely in the press as well as academia, with his impact evident in the books he wrote, the public interventions he made, and the scholars he mentored. That impact will far outlive him, even if as the University of Warwick’s vice-chancellor said, “[Anwar] will be much missed by everyone, from postgraduates to policy makers, who benefited from his insight and support.” I think that is incredibly true. I know that I will miss him.

Dr. H.A. Hellyer is senior associate fellow at the Royal United Services Institute in the UK & the Carnegie Endowment for International Peace in the USA, and a visiting professor at the Centre for Advanced Studies on Islam, Science and Civilisation in Kuala Lumpur. He is also a professorial fellow of Cambridge Muslim College in the UK, and senior scholar of Azzawia Institute in Cape Town. Among his publications include the books “A Revolution Undone: Egypt’s Road beyond Revolt”, “Muslims of Europe: the ‘Other’ Europeans”, and “A Sublime Way: the Sufi Path of the Sages of Makka”. He is currently on the steering committee for a multi-year EU-funded project on ‘Radicalisation, Secularism and the Governance of Religion’, which brings together European, North African and Asian perspectives with a consortium of 12 universities and think-tanks.

*Image:https://www.theguardian.com/world/2020/jun/29/muhammad-anwar-obituary