While browsing through old journals we often encounter a name that repeats itself frequently enough to be noticed, yet buried away from the allure of the front page. Throughout many months and years, these semi-visible authors weave their stories about local communities into larger flows and currents deemed more important: world crises, social problems, stubborn ideologies and imperial structures that are just one assassination away from crumbling. In a certain way, these lesser known journalists and authors show what is actually constant, which is the humdrum and perseverance of a common life. At the same time, their fate is more precarious than that of a Ginzburg’s Menocchio, since their presence is not an aberration, but a relegation to a supporting role in the waters of history. It is possible, as Lale Can suggests in her new book, to call them ”ordinary people”[1] who at the same time ”subvert these categories”[2] (of ”ordinary people, subalterns, and elites”). The fact that many of these early twentieth century authors wrote in popular media, contributed to religious debates and heavily consumed the modern products of photography and telegraph, speaks about the rapid crossing of visibility lines in a short period.

“Despite authoring one of the most extensive Hajj travelogues in Bosnian history, which encompassed a portrayal of religious experience, lively scenes from the cities of the interwar Middle East, encounters with religious elites, and consumerist confessions, Krpo remains a rather unknown figure in the local context.“

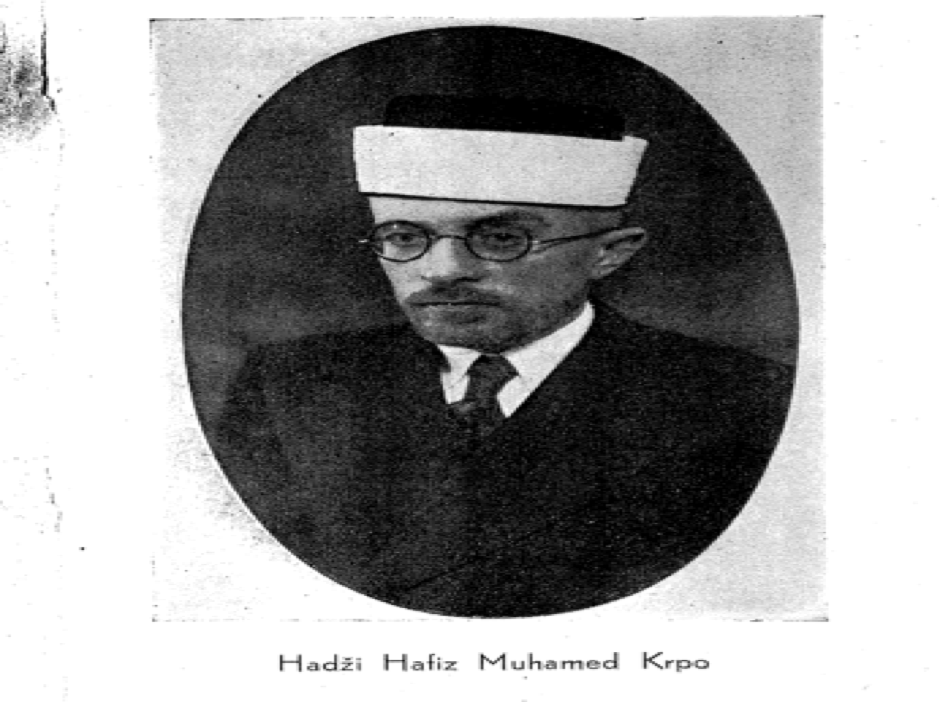

Ambiguity is precisely what I felt about Muhamed Krpo, a Bosnian ʿalim and travel writer, as I was beginning my research on Bosnian Hajj writings. Despite authoring one of the most extensive Hajj travelogues in Bosnian history, which encompassed a portrayal of religious experience, lively scenes from the cities of the interwar Middle East, encounters with religious elites, and consumerist confessions, Krpo remains a rather unknown figure in the local context. Rereading his work in the age of quarantine and cancelled pilgrimages highlights common fears and anxieties related to diseases and national borders, but also points to the persistent human need to communicate across the rigid boundaries set by circumstances, custom or extraordinary events. And finally, Krpo’s incisive descriptions peppered by light-hearted remarks underscore the existence of humour in both the holy and harrowing.

Krpo’s name starts appearing early in the twentieth century on the blooming Bosnian print scene. During the late period of Ottoman rule in Bosnia, several bilingual journals were published, including Bosna and Sarajevski cvjetnik (Gülşen-i saray). During the Austro-Hungarian rule (1878-1918), more journals were established, presenting different political and ideological outlets while also mediating between specific social groups (such as the ulama) and the wider public. Apart from the journals, a growing number of authors from different educational backgrounds (some of whom were educated in places like Vienna, Istanbul or Cairo) also published monographs or translated books from Arabic and Ottoman Turkish. In the midst of this, editors and journalists kept close correspondence with their counterparts across the Ottoman Empire, later Turkey, Syria, Egypt and beyond.[3] At the same time, local opinion also mattered, which is why letters of enthusiastic readers were encouraged, albeit somewhat patronised with cynical comments by editors as well.

“Around 1917, Krpo seems to have started working in a mosque in Mostar where he was born, sponsored by a renowned politician and businessman Mujo Komadina, a former mayor of the city. He apparently also taught children in a maktab.“

Around 1917, Krpo seems to have started working in a mosque in Mostar where he was born, sponsored by a renowned politician and businessman Mujo Komadina, a former mayor of the city. He apparently also taught children in a maktab. Turbulent times and a precarious career path, combined with Krpo’s own conspicuously adventurous personality, made him move and work between different places. After Mostar, Krpo served in Konjic, Travnik, Hrasnica and Visoko where he died in 1965. During the Second World War, Krpo left the religious for civil service, although he continued writing for ulama journals throughout the period, as well as reciting the Qur’an to provide consolation during the wartime horrors. After the war, he retired but continued to actively participate in the local džemat in Visoko, writing reports about problems facing the imams in the postwar socialist period, as well as pointing to the rising drinking problem among the people.

He was an imam, but also a muadhdhin, and since he was a hafiz with a mellifluous voice, he was often invited to recite the Qur’an and participate in mawlid ceremonies across Bosnia and beyond. In the latter, he read the text popularly called ”Bašagić’s mawlid”, composed by a Bosnian Orientalist and poet Safvet-beg Bašagić (1870-1934) in the style of earlier devotional poetry dedicated to Prophet Muhammad’s birth. Some time before the World War II, Krpo was invited to Zagreb to recite the Qur’an ”for us Muslims in Zagreb, at the threshold of Central Europe”, and people weeped in joy.

At the same time, Krpo loved to participate in different facets of the journalistic culture. The first time his name appears on the pages of Novi Behar is related to a successfully resolved riddle from a previous issue. He used a pseudonym – Kriticus – in the style of the age. However, contrary to many authors of his time, he also used the medium of advertisement for his greatest desire: to go on a Hajj. Krpo already went on Hajj in 1931, but wished to go again although he did not have the means. This led him in 1933 to post an advertisement in Islamski svijet (Islamic World), squeezed between marriage notices, announcements for burial societies for poor Muslims and news about journal ”Islamic Culture” in Hyderabad. He briefly explained that he offered badal service, in return for paid costs because he wanted to go on Hajj, but was unable to do so. To support his case, he listed German, Arabic and Turkish as languages he knew which would make him a very suitable guide to many Yugoslav Hajjis.

“Krpo already went on Hajj in 1931, but wished to go again although he did not have the means. This led him in 1933 to post an advertisement in Islamski svijet (Islamic World), squeezed between marriage notices, announcements for burial societies for poor Muslims and news about journal ‘Islamic Culture’ in Hyderabad. He briefly explained that he offered badal service, in return for paid costs because he wanted to go on Hajj, but was unable to do so. To support his case, he listed German, Arabic and Turkish as languages he knew which would make him a very suitable guide to many Yugoslav Hajjis.“

Several years later, Krpo went on Hajj and published his travelogue in the year after. He still did not have enough money to visit Medina, but felt obliged to fill the gap with standard descriptions of the Prophet’s mosque and Rawda. Despite having limited resources, Krpo started his journey in high spirits which he kept throughout. That year, Krpo was an imam in Hrasnica, a small place near Sarajevo, where he joined other Bosnian Hajjis for the start of the journey. They travelled under the organisation of the travel agency ”Putnik” which also sold tickets for Orient Express that passed through Yugoslavia.[4] The pilgrims were vaccinated against smallpox and cholera, which was a requirement by Egyptian authorities. Thirty five years after Krpo went on Hajj, Yugoslavia suffered from the last outbreak of smallpox in Europe. Since it was assumed that outbreak was caused by a returning Hajji, Yugoslav pilgrims in the 1970s often faced suspicion and prejudice.

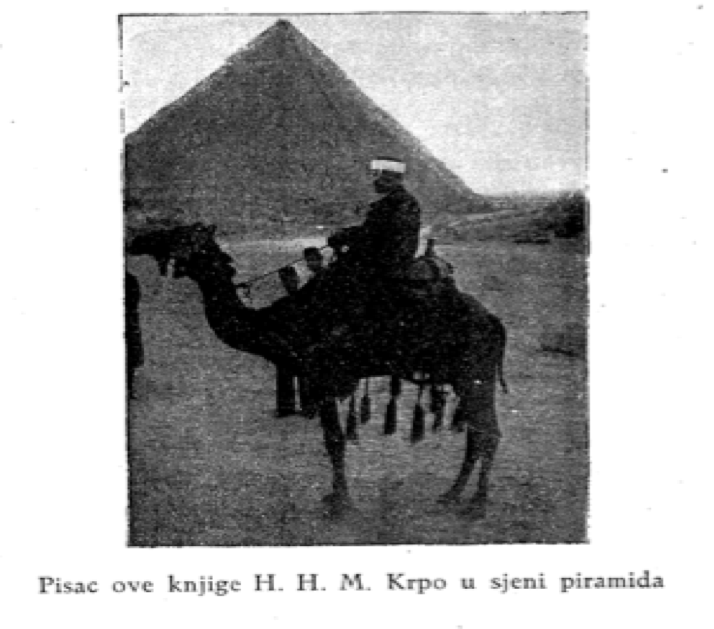

But all of this was far from Krpo and his companions. After emotional farewell ceremonies in Hrasnica and Sarajevo, the Hajjis were on their way to Athens, where they waited for visas for the next stage of their journey. Krpo was especially jovial because he met another fellow Hajji interested in photography – they were both ”photo-amateurs.” In a desire to bring the journey closer to widening audiences, the travelogue contained a number of photos taken by Krpo, as well as reproductions he bought presenting ”types” of people living in the Middle East. His choice of photos was inevitably gendered, prompting questions about inter-Muslim objectivisation and the influence of popular travel literature on verification of experience through something akin to an ethnographic method. That such evidence was valued shows in one of the reviews of the travelogue which stated that the photos were ”too blurry.”[5]

“Throughout his journey, Krpo showed himself to be an avid consumer of many modern things: he smoked scented ”Papastralos (sic)” cigarettes, listened to the gramophone on the deck, and with other Hajjis rented ”luxurious car” that could reach a shocking speed of 40 km per hour.“

While Krpo and his Hajjis did not pass through Istanbul, the shadow of the bygone Ottoman rule was present in Athens, particularly in the way Yugoslav Hajjis were treated. Thus Krpo narrated how he was almost physically attacked by an angry young man who thought he was a Turk; an old woman was startled when she saw his headgear so she crossed herself multiple times; at the Theseum, English tourists took photos of the Yugoslav Hajjis instead of the temple; and when they tried to reach the metro, people surrounded them thinking they were part of a costume party, leading their exasperated guides to call the police. Still, Krpo harboured no bad feelings: for him, the Greeks were clever, pious and overall friendly to Yugoslavs and he genuinely wanted to know more about them. After all, as he pointed out to some reluctant Hajjis standing in front of the shrine, the Qur’anic injuction of sīrū fī al-arḍ compelled Muslims to learn from the past and apply the knowledge in present.

Throughout his journey, Krpo showed himself to be an avid consumer of many modern things: he smoked scented ”Papastralos (sic)” cigarettes, listened to the gramophone on the deck, and with other Hajjis rented ”luxurious cars” that could reach a shocking speed of 40 km per hour. The feats of modern industry still puzzled many Hajjis: passing by a strangely shaped factory in Tanta, the Hajjis raised their hands to recite the Fatiha thinking it was the shrine of Sayyid Ahmad Badawi, which made Krpo and other travellers burst out laughing.

After the exhausting sea journey, during the detour in Cairo, Krpo decided to see Nashīd al-amal, the latest movie by Umm Kulthum, a famed performer and actress:

“For two and a half hours I listened to that melodious voice, a sad lullaby for the sick child by the mother abandoned by a tramp, the voice of a huri who is enchanting and the song that can be only Arab. I watched a movie about the Arab exotic from the life of the Cairo underground. To listen to the voice of Umm Kulthum means to leave the earthly life. It is to be in heaven listening to a huri, who does not seem to be a mortal being.”

Krpo’s delight was not appreciated by an anonymous reviewer of his travelogue, who wrote that this description is more suitable for a bon vivant (teferičlija) than for a Hajji.[6] But Krpo certainly did not see himself as yet another tourist, and he criticised those that spend their money on visiting places of ”culturally fake Europe” instead of going on a Hajj. The pilgrimage was the pinnacle of a believer’s life, but at the same time, it was consistently evoked as a unifying tool for the Muslim community. The exact contours of such unity were often vague; in Krpo’s case, it often collided with individual national claims for decolonial action and sovereignty.

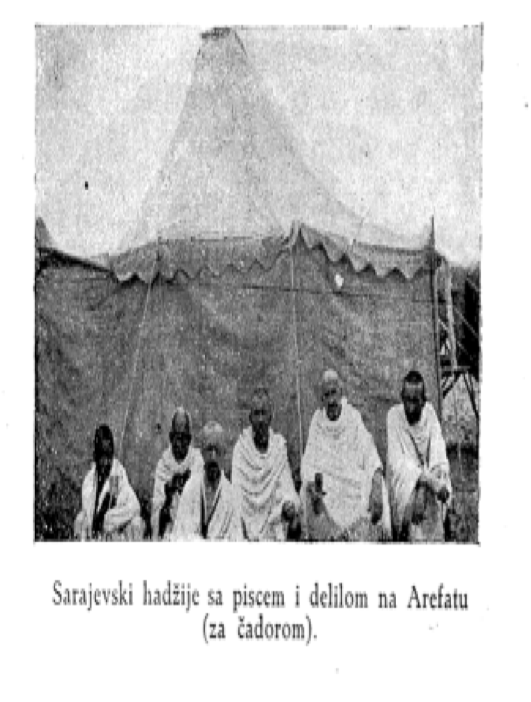

In the cities he passed through, Krpo met with consuls and diplomats (Yugoslav, but also foreign), politicians, journalists (highlighting his connection to circles of Muslim modernists across the Middle East), businessmen, and even the king Abd al-Aziz (his photograph, as well as his son’s, were also reprinted in the travelogue). Yet, Krpo and his companions took delight in meeting ordinary people, and especially dalils or pilgrimage guides with connections to Bosnia. Passing through Damascus and Cairo, and even in Mecca, the Hajjis were particularly interested in meeting the muhajirs, people who left the Balkan region in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, often in fear that they will be unable to practice Islam under Austro-Hungarian rule.

While meetings with various people brought out the lively and humorous in Krpo’s narrative, his thoughts on the state of the world seem somber and overtly political. Thus, the call for Muslim unity and solidarity at Hajj – a standard trope of the age – merged with praise for the Saudi Kingdom and its rule. Krpo is adamant that the Qur’an is used as the ”constitution of Hijaz,” that the wrong-doers are punished and that safety abounds (”Arab police is faster than Scotland Yard!”). It would seem that his narrative hardens at this point because it is also directed to dispel some of the claims about slavery and prostitution in Hijaz that circulated in newspapers published in Belgrade. The critique of Hajj and Islamic sacred geography in Yugoslav media and Orientalist scholarship was part of larger objectivisation of Muslims, where, especially in the case of Bosnian Muslims, their religious difference and ethnic in-betweenness made them ambiguous figures of (br)others in rising Croat and Serb nationalisms.[7]

“Yet, Krpo was not an uncritical observer of the rapid changes happening in Hijaz. While trying to perform the rite of saʿy (running between Safa and Marwa), he was prevented by the King’s entourage and many wealthy Egyptians and Iraqis who drove their luxurious limousines seven times between the two spots.“

Yet, Krpo was not an uncritical observer of the rapid changes happening in Hijaz. While trying to perform the rite of saʿy (running between Safa and Marwa), he was prevented by the King’s entourage and many wealthy Egyptians and Iraqis who drove their luxurious limousines seven times between the two spots. The police and army forced ordinary Hajjis to step aside and wait in the midst of the uproar and choking stench of oil. Krpo was once again reminded of his poverty. The rites of Hajj that embodied the absolute ”democracy of Islam” which guaranteed the equality of all Muslims regardless of the class were now being hijacked by ”conceited rich, capitalists and moguls.” The images of wealth, oil and opulence are contrasted with a story about Hajar who ran in despair and anguish to find water for her newborn son.

Despite being candid about different facets of the journey, Krpo is surprisingly reserved when discussing his own religious experience. Descriptions of holy rites and places are directed to guide the reader/potential pilgrim, with occasional remarks about new regulations (”there were more rites before the Wahhabis came, because there were more places of ziyarat”). Only the close proximity of Bayt Allah causes Krpo to write:

“I was never more touched as during the recitation of du’a after first tawaf, in front of the Ka’ba, and this is what happens with every Hajji who comes to perform the religious duty – Hajj – as a true believer.”

This way, the emotion that resurfaced through ritual became a marker of true belief, and potentially a sign that the goal has been accomplished. In the process, the persona of Hajji took precedence over Hajj in description and narration.[8] After the intense physical and emotional experience in Mecca, the journey back turned out to be a slow denouement, filled with waiting for visas and other documents which for tired and cash-strapped Hajjis seemed to be almost intentionally exhausting. The intense anxiety was exacerbated by the quarantine of Krpo’s ship in Al-Tur, which placed the Hajjis in a state of constant dread: will they be allowed to sail to the Suez? Or will they be detained endlessly because someone has a contagious disease?

The Hajjis were finally let go and they continued on their way, listening to the fiery speeches of Syrian anticolonialists who ignored them and ”thought they were superior to us.” But then Bosnian Hajja Sharifa asked Krpo to ”recite something, so that Arabs hear how even Bosnians know things.” And indeed, after Krpo read a sura from the Qur’an, their snooty fellow travelers fell silent in awe and their respect towards the Bosnians increased tenfold. The Hajjis continued on their way through Sham, visiting tombs of the Prophet’s family members and awliya.

“…the Hajjis were stopped at the Yugoslav border and accused of smuggling goods into the country. Some of them were arrested, which prompted Krpo to use all his connections to reach Mehmed Spaho (1883-1939), a Bosnian politician and leader of the Yugoslav Muslim Organisation.“

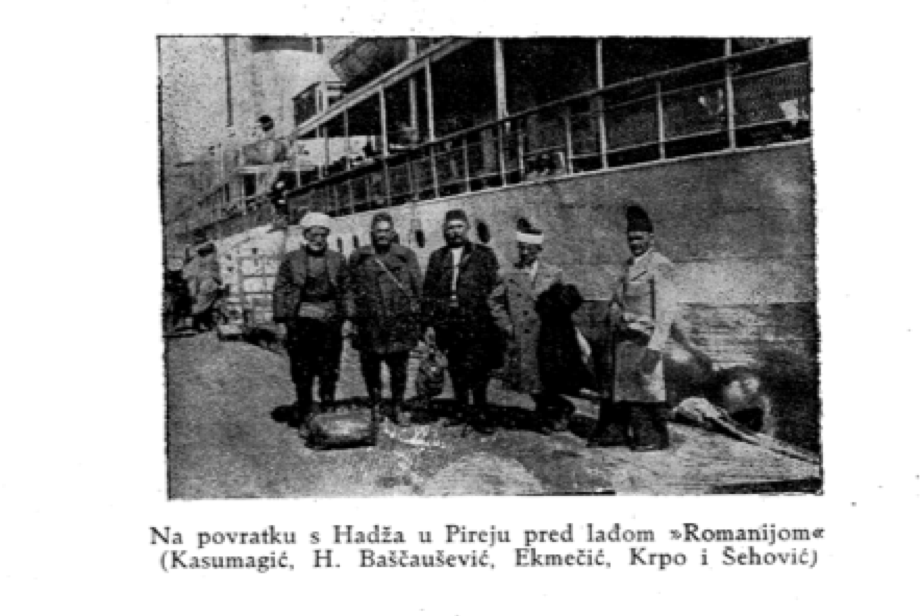

Bosnian fame, unfortunately, could not save them from further troubles. After a rather tumultuous sea journey and exhausting train ride, the Hajjis were stopped at the Yugoslav border and accused of smuggling goods into the country. Some of them were arrested, which prompted Krpo to use all his connections to reach Mehmed Spaho (1883-1939), a Bosnian politician and leader of the Yugoslav Muslim Organisation. While the Hajjis were ultimately released, this was another experience to be added to the list of marginalizations suffered by the Bosnian Hajjis during their most sacred journey.

Thus, it is necessary to understand that writing about Hajj assumed a new urgency, which Muhamed Krpo recognized: it was a way to assert equal participation in the rising print culture. At the same time, engaging in this public sphere meant speaking to diverse reading audiences, which gave Krpo an opportunity to explain the rites, inform potential pilgrims, expose the dangers lurking on the way and even directly polemicize with critics.

The narrative and descriptive world of Muhamed Krpo might not be the same as the world of Nasir-i Khusraw or Evliya Çelebi, and it seems nostalgic enough for our reading tastes today, but this travelogue is at its essence a testimony to a constant state of wonder that found no event, place or person too small and insignificant to merit due attention.

Finally, Krpo’s writing impulse conveys the wish to turn the Hajj into a shared experience for many (perhaps even the majority of) Muslims who will never be able to go on the pilgrimage. However, unlike the rahhāla of the past, Krpo wrote for non-Muslims too, mediating more than his religious experience. It remains a testimony to a culture of travel in the interwar period, a time inevitably passed but mirroring ours in a myriad of unexpected ways.

Dženita Karić is an intellectual historian currently moored in Tubingen, where she was a Teach@Tubingen fellow for 2019/2020. Her book project treats Bosnian Hajj literature in a longue duree perspective, tracing changes and transformations in the way the pilgrimage was conceptualised. Her major research interests include religious transformations, devotional genres, mobilities in Islam, and gender.

[1] Lale Can, Spiritual Subjects: Central Asian Pilgrims and the Ottoman Hajj at the End of Empire (Stanford: Stanford University Press, 2020), 31.

[2] Ibid, 37.

[3] Such close relations enhanced by journalistic correspondence often led to larger ideological influences between Bosnian and late Ottoman ulama. Harun Buljina, ‘’Empire, Nation, and the Islamic World: Bosnian Muslim Reformists between the Habsburg and Ottoman Empires, 1901-1914’’ (PhD Diss., Columbia University, 2019), 188

[4] Popov D. in Živana Krejić and Snežana Milićević, ”Nastanak putničko-agencijske delatnosti u Jugoslaviji kao pokretača razvoja kulture putovanja,” Kultura 161 (2018): 43

[5] Anonymous, ‘’Hadži Hafiz Muhamed Krpo: Put na hadž,” Novi Behar XI, 17-19 (1937-38): 291

[6] Ibid.

[7] (Br)other is a figure that is neither enemy nor ally, neither “ours” nor “theirs,” neither “brother” nor “Other” (Edin Hajdarpašić, Whose Bosnia? Nationalism and Political Imagination in the Balkans, 1840–1914 (Ithaca and London: Cornell University Press, 2015), 16.

[8] Metcalf, Barbara. ”The Pilgrimage Remembered: South Asian Accounts of the Hajj,” in Muslim Travellers: Pilgrimage, Migration, and the Religious Imagination, ed. Dale F. Eickelman and James Piscatori (Berkeley and Los Angeles: University of California Press, 1990), 87