In Indonesia, like elsewhere, Islam and Marxism have an historical relationship largely characterized by opposition. Notably, there was an historical moment during the late colonial and early independence eras when a tradition of Islamic communism gained relative prominence. However, the possibility of this Islamic brand of communism (along with all others) was annihilated in the nationwide politicide of communists in 1965-66, when Islamic paramilitary organizations and gangsters joined the CIA-backed Indonesian military in slaughtering an estimated 500,000 suspected communists. Over the subsequent long authoritarian rule of Suharto’s New Order, anti-communist propaganda became a mainstay of public discourse and schooling, while a bourgeois-style Islam increasingly entered the mainstream. And while Indonesia has experienced a flood of new critical discourses during the post-Suharto Reformasi era (1998-present), including some grassroots Left movements, communism remains a political boogeyman, treated as a still-lurking existential threat to the nation and to Islamic public morals.

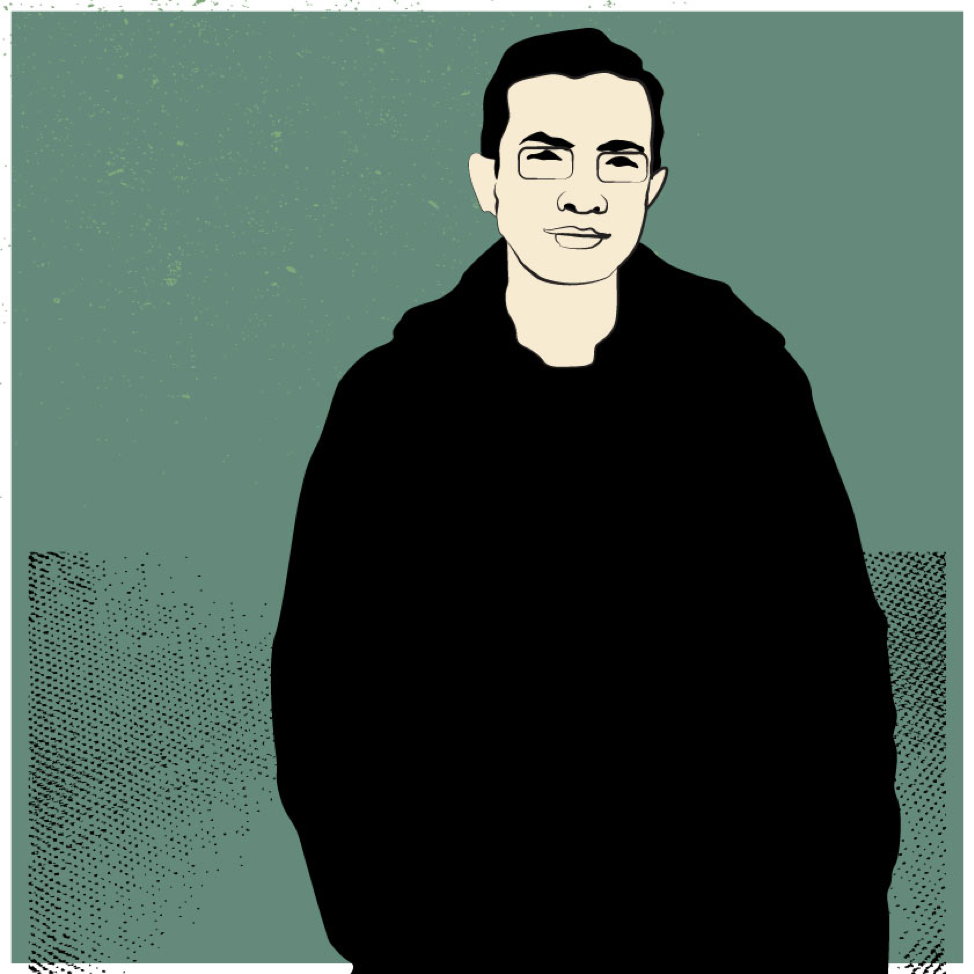

This context makes the recent emergence of an Islamic Left—organized around a few online spaces, academic institutions, and grassroots movements—all the more exceptional. Here, I explore the popular writings of Muhammad Al-Fayyadl, a leading contemporary intellectual within this movement. Most noteworthy is his project of “progressive” Marxist analysis from within the discursive framework of Indonesia’s tradition of ShāfiꜤī fiqh. He departs from more moderate precedents within the history of Islamic socialist thought by openly embracing Marxist analysis and advocating a “materialist” approach to Islamic regulation of social life, all while remaining grounded in traditionalist Islamic scholarly modes of reasoning.

“Fayyadl’s novel framing seeks to open up new and important discursive space from within which traditional Islamic scholarship might be used to engage with Marxist thought and critique capitalism.”

Fayyadl grew up in, and now teaches in, Java’s traditionalist network of pesantren (Islamic boarding school), which is united around the mass popular and civil society organization Nahdlatul Ulama (NU), whose paramilitary branch once played a major role in the 1965-66 communist killings. His grounding in this discursive tradition not only represents a major departure from NU’s historical opposition to the Left; it also distinguishes him from most other famous historical Islamic socialist thinkers, who have adopted more modernist modes of Islamic thought—i.e. less committed to classical Islamic scholarly precedent. This complicates a common conceptual dichotomy that pits “progressive” against “backward-looking” forms of Islam. Fayyadl’s novel framing seeks to open up new and important discursive space from within which traditional Islamic scholarship might be used to engage with Marxist thought and critique capitalism.

Islamic (Neo)Liberalism and its Discontents: the “Progressive Muslims”

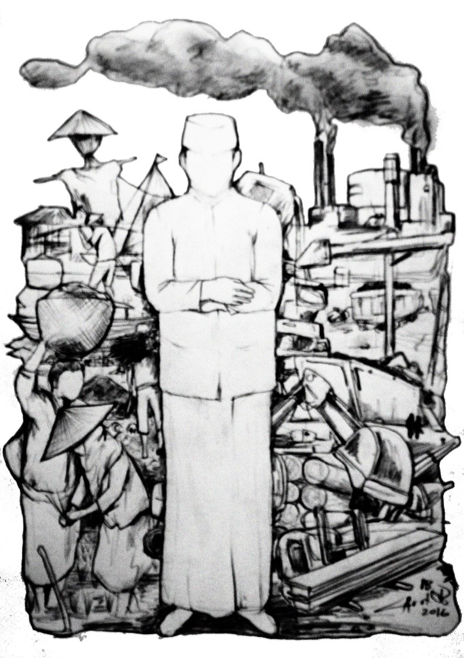

Fayyadl’s thought is situated within a broader resurgence of capitalist-critical discourse and activism in response to the political and economic developments of the past two decades. In the wake of the 1997 Asian financial crisis, 1998 saw not only a successful mass movement to oust the autocratic Suharto, but also a $40 billion bailout package from the IMF conditional on Indonesia’s privatization of state industries and elimination of protective tariffs. This has resulted in, on one hand, increasing struggles for small-scale farmers and workers in the face of global capital, and, on the other, a proliferation of different forms of neoliberal and prosperity-oriented Islamic discourses.

The most systematic critiques of both these trends (material and discursive) have come from a group of young Islamic intellectuals and activists like Fayyadl who refer to themselves as, among other terms, “progressive Muslims.”

In Indonesian, the English loan-words liberal and progresif are related in a similar way as they are in contemporary English usage. Many self-identified liberals—who support women’s and minority rights and oppose state intervention in citizen’s personal freedoms—also often refer to themselves as progressives and even often use the two terms interchangeably. However, many within the Indonesian Left identify as “progressives” and use the term “liberal” disparagingly to refer to those who primarily concern themselves with individual rights rather than issues of structural economic exploitation. This is the rupture that Fayyadl highlights when he declares: “It’s time to divorce Islamic liberalism from the term ‘progressive’,” insisting that middle-class liberal Muslims only seek “progress” for their own class interests.

A particular target of these progressive Muslims’ critiques has been the group called the “Liberal Islamic Network” (Jaringan Islam Liberal, or JIL). Polemics against JIL have been well-covered in English-language media and scholarship, but they have largely been framed as fundamentalist reactions, supporting the narrative of a “conservative turn” in Indonesian Islam. While it’s true that most public criticism of JIL has principally opposed their non-literalist and “deviant” teachings, this narrative elides the voices of a subsection of JIL’s critics who, not bothered by their tolerance of minorities or feminism, attack them for their economic liberalism.

An intellectual precedent to JIL was the movement for Islamic “renewal” that began to emerge in the 1970s, with close ties to the authoritarian state under Suharto. A prominent “renewalist” thinker during this era, Nurcholish Madjid (popularly called Cak Nur), while claiming to advocate what he called “religious socialism,” actually opposed state intervention in the market. During the period of democratization and market liberalization after the fall of Suharto in 1998, JIL thinkers—backed by Western NGO funding—have also presented market liberalism as a logical and necessary component of their larger projects of religious and social liberalism. Drawing on Cak Nur’s writings on political secularization, JIL co-founder Luthfi Assyaukanie argued in a 2009 blog post that, just as the state should not intervene in matters of religious life, so it should also refrain from interfering in the market. In a 2015 article on JIL’s website, co-founder Ulil Abshar-Abdalla cites a hadith in which the Prophet refused to impose price limits in a Medinan market, arguing that he was therefore a “marketist” who “truly understood how the mechanism of the ‘invisible hand’ works in the market.”

Progressive Muslim thinkers have been launching increasingly frequent attacks on this mode of Islamic liberalism that paints capitalism as Islamic. But unlike JIL’s conservative critics, these progressives see JIL not as a fringe anomaly, but rather as, in some ways, an intellectual vehicle for ruling class ideology. The liberal trend does differ from mainstream Islamic doctrine on certain issues, but in terms of economic ideology, it helps reproduce hegemonic ideas about Islam’s passivity towards market injustice. Indeed, many liberal and conservative Muslim intellectuals have cooperated in the development of “sharia banks,” in what Fayyadl calls an “Islamization of capitalism.” He emphasizes the importance of asking “who these discourses serve,” as it “involves complex power relations between Islamic liberalism, funding agencies, and global agendas that maintain colonial and imperialist dispositions toward the Third World.”

In a particularly telling example of his criticism of JIL, in 2018 Fayyadl leaked on Facebook a copy of an invitation to a corporate gala held by a major mining and energy company, at which JIL’s Abshar-Abdalla was slated to speak on “Islam that Yearns for Indonesian National Unity.” In an attached comment, Fayyadl highlights the irony of Abshar-Abdalla “speaking about national brotherhood before a crowd of mining executives, whose businesses divide and destroy the earth of the Indonesian nation.”

Fayyadl and these progressive Muslims have mobilized both to attack this Islamic neoliberalism and to forward an alternative Islamic political-economic vision. Fayyadl helped launch in 2014, and now frequently writes for, an online magazine called Islam Bergerak (Islam that Moves), which often publishes content advocating for the rights of farmers, the protection of the environment, and the compatibility of Islam and Marxism. The name is in homage to a publication by the same name launched in 1917 in Central Java by the communist Muslim activist, Haji Misbach, famous for his treatise, Islamism and Communism (which I recently translated).

Fayyadl also moves fluently within Marxist and broader intellectual spaces that are not explicitly Islamic in orientation. After completing his undergraduate degree at a public Islamic university, he studied philosophy at Université Paris 8, where he recalls meeting and drawing inspiration from radical activists from around the world. He is also a frequent contributor to the popular online Leftist magazine IndoPROGRESS, and he once even quipped in an interview that Islam Bergerak was simply the “Islamic branch” of IndoPROGRESS.

But how precisely does Fayyadl articulate this “progressive” Islam, and how does he make Marxism fit into traditionalist Islamic scholarly disciplines? Since he has not yet written a summarizing tract on his method, I engage his thought through an array of interviews, editorials, and widely-shared Facebook posts.

Marxism in Fiqh

The major point of departure for Fayyadl is a recognition of capitalist relations and their effects—mainly inequality and environmental destruction—as constituting a normative problem from an Islamic perspective. In advice to students at Islamic boarding schools, Fayyadl writes:

First off, we need to treat capitalism like a serious issue within our religious scholarship, so that we will need to promote critical approaches to the study of capitalism. … for example, there is May Day. [One might wonder,] “Why are there laborers in the streets?” If we students of Islam lacked understanding, then we would think that those protesting have nothing to do with religion. On the contrary, however, this is a part of fighting for rights, which is commanded by religion.

In response to this disposition of apathy toward the conditions of the poor, Fayyadl insists that the umma is in need of “materialist” religiosity and fiqh. In a 2016 article he writes:

What is a way of being Muslim (keberislaman) that is materialist? It is a way of being Muslim that begins with concrete social conditions, filled with inequality, discrepancies, and contradictions between “what should be” and “what is,” that is sensitive to shifts and changes in material facts that surround those social conditions, that is driven to revolutionarily change those social conditions through reference to the sources of Islamic teaching.

Here, Fayyadl echoes Ali Shariati’s concept of “Islam as ideology,” which seeks rectification of “the contradiction between existing (is) and ideal (ought) conditions.” But a crucial element to Fayyadl’s vision is left open-ended here: what do “the sources of Islamic teaching” have to say about “what should be” in terms of socio-economic conditions?

In other writings, this approach is constructed on some basic axiological principles. Fayyadl frequently cites the Qur’anic admonishment of “accumulation of property” (takatsur, Ar. takāthur) as an indictment of capitalist practices of profit maximization. He writes that a true pious materialist “believes that the sharia, if it really brings mercy, could not involve aspects that are exploitative or harmful of others.”

However, despite the identification of Islam’s socio-economic egalitarian values, Fayyadl finds dominant traditional approaches to Islamic legal scholarship (fiqh) largely incapable of overcoming issues of inequality and exploitation, since, in the ShāfiꜤī legal school (traditionally followed in Indonesia), and fiqh more broadly, jurists’ normative gaze is generally focused at the level of individual interactions, not large-scale economic relations. In a 2019 piece entitled Marxism and the Way Towards a Liberation Fiqh, Fayyadl makes three important methodological moves in order to overcome the limitations of this atomistic approach with a more socially-minded (sosialistik) one.

First, he focuses on a traditional distinction within Islamic legal scholarship between two levels of legal analysis: the “rulings of accountability” (aḥkām taklīfiyya)—like forbidden (ḥarām), permissible (ḥalāl), mandatory (farḍ), etc.—and the “rulings of condition” (aḥkām waḍꜤiyya)—like requirement (sharṭ), necessitating factor (sabab), and preventative factor (māniꜤ). In Islamic legal reasoning, a particular action (like prayer) may carry a different status of accountability (forbidden, permitted, mandatory) depending on certain conditions, including: requirements (the individual having reached puberty), necessitating factors (the sun’s position in the sky), and preventative factors (a state of ritual impurity). Fayyadl seeks to use the latter category of “rulings of condition” to make room for a progressive, “emancipatory” fiqh. Without elaborating his methodology fully, he explains:

Now, an awareness of political economy and materialism can be built on the level of these rulings of condition. There, we can see that, if the material reality is full of injustice, then it must be prevented or opposed. Of course, when referring to the rulings of accountability, there is no revealed legal evidence (dalil fikih) that says that “capitalism is forbidden,” because the term “capitalism” was not yet known by the classical scholars of Islamic law. But, if seen from the perspective of rulings of condition, we can ask, is capitalism a cause of harm? If so, as a consequence we can declare its practice forbidden.

Here, he uses the negative social impacts of capitalist practices as a “preventative cause” (māniꜤ) to overturn their permissibility. This methodological foregrounding of “social harm” and “social benefit” brings us to his second major methodological move.

In this second step, Fayyadl draws on a traditional Sunni legal discourse on the “higher objectives of the sharia” (maqāṣid al-sharīꜤa), in which certain overarching values are identified within the divine law, namely the protection of life, intellect, faith, progeny, and property. The theoretical framework for the maqāṣid was laid out in the classical period by al-Juwaynī (d. 1085) and his pupil al-Ghazālī (d. 1111), but it was only later that scholars like Ibn ꜤAbd al-Salām (d 1262) and al-Shāṭibī (d. 1388) proposed elevating these higher objectives to a position where they could be used (and indeed must be considered) by a jurist as the basis for a legal ruling. In modern Sunni thought since the late nineteenth century, the framework has gained popularity among legal thinkers as an indigenous framework for expanding legal thought beyond a traditional corpus perceived as ossified and unresponsive to social conditions.

“Of course, when referring to the rulings of accountability, there is no revealed legal evidence (dalil fikih) that says that “capitalism is forbidden,” because the term “capitalism” was not yet known by the classical scholars of Islamic law. But, if seen from the perspective of rulings of condition, we can ask, is capitalism a cause of harm? If so, as a consequence we can declare its practice forbidden.”

While attempting to overcome traditional jurisprudential constraints, Fayyadl’s invocation of maqāṣid remains coherent within the legal discourse of Indonesia’s traditionalist Muslim community, since the theory’s genealogy is traced back to authoritative scholars of the ShāfiꜤī school (to which Juwaynī, Ghazālī, and Shāṭibī belonged), from which most Islamic legal literature studied in Indonesia’s traditionalist pesantren is drawn. Here, and in his larger engagement with traditional Islamic legal scholarship, we are reminded that, unlike most recent innovative Indonesian Islamic legal thinkers, Fayyadl still draws authority from within the realm of traditional ShāfiꜤī scholarship.

From this literature on “higher objectives,” Fayyadl draws a legal framework for prioritizing social welfare (maṣlaḥa) and avoiding social harm (mafsada). He offers the following hypothetical:

For example, we are faced with a case of the establishment of Company A in a certain location. After evaluating its social benefits (maslahat) and social detriments (mafsadat), it turns out that in the long term, its detriments will be greater, since the company will destroy the economic independence of the surrounding community, for example. Then it can be declared forbidden (bisa diharamkan). The solution would be to change it to a different type of business that would not have such an effect.

This method clearly opens up Islamic legal thought to the possibility of systematic structural critique rather than focusing simply on the “permissibility of [individual] transactions.” But how might Fayyadl (or his hypothetical jurist) conclude that a particular company would, “in the long term… destroy the economic independence of the surrounding community”?

Here, we find the third major conceptual move that undergirds this discourse of progressive fiqh. Enter Marxism. In discussing the same case of Company A, Fayyadl continues, “This [ruling] would only be possible if we have an understanding of relations of exploitation, the nature of capital, and similar topics of analysis in Marxism.”

Here, Fayyadl makes the critical move of integrating Marxist social analysis into the internal reasoning structure of Islamic jurisprudence. It may seem unprecedented to integrate a Western social-scientific mode of reasoning into an Islamic sacred science, but it is worth recalling that Islamic legal scholarship has long integrated both Greek logic and medical expertise into its internal rationality. Logic, like Arabic grammar, is referred to as a “tool science” (ilmu alat) in traditional pesantren education. Likewise, rulings for many Islamic legal issues depend on the medical condition of the individual, to which regimes of medical knowledge have long been crucial factors in Islamic jurisprudential reasoning.

Trends within recent Indonesian Islamic thought, especially within the world of public Islamic universities, also help facilitate this conceptual move. Since independence, scholars in the public Islamic college system who undertook graduate studies at Western universities (especially McGill) have returned to advocate the study of social sciences for students of Islam, resulting in the founding of scientific faculties on these campuses. More recently, Amin Abdullah, a former rector (2001-2010) of the influential Sunan Kalijaga State Islamic University in Yogyakarta (Fayyadl’s alma mater) popularized a paradigm of “integration and interconnection of sciences” (integrasi-interkoneksi ilmu), in which he encouraged engagement with Western social scientific ideas within Islamic religious scholarship. Literature in the Marxist tradition, especially Gramsci, along with works from the global Islamic Left, like Hasan Hanafi, have become a staple in this diet of Western social theory.

Likewise, Fayyadl positions Marxism as “an intellectual tool” (perangkat ilmiah) or a “science” (ilmu) to “dissect capitalism.” Elsewhere, he explains:

Marxism could be treated otherwise as mirror upon which we Muslims can look at our own destructed face and compare it to the liberating mission of Islam. If Islam provides an ideal of egalitarian society based on a classless society, liberated from any accumulation of private property (takatsur fil amwal), the most difficult question is how to bring this ideal back to earth? It is almost impossible to reply to such question without taking Marxism as a guide to clear up what the “accumulation” is. It does not suffice then to denounce the capitalism without understanding clearly the nature of “capital”, which is more than money or property.

Marxism here, “as a guide” to “understanding clearly the nature of capitalism,” is taken up as an authoritative science on the nature of the social body in a way similar to how medical knowledge explains the nature of the human body.

“Marxism here, “as a guide” to “understanding clearly the nature of capitalism,” is taken up as an authoritative science on the nature of the social body in a way similar to how medical knowledge explains the nature of the human body.”But this identification of Marxism as an “intellectual tool” to be integrated into a traditional Islamic science requires that the social-analytic dimension of the Marxist tradition be stripped from its famously atheistic philosophical underpinnings. Fayyadl has explicitly distinguished between three facets of Marxism when considering its compatibility with Islam. In his view, (1) ontological materialism contradicts an Islamic religious worldview. But he affirms (2) the axiological compatibility of Islam and Marxism, asserting that both fight to end inequality and injustice. Crucially, he also argues that (3) epistemologically, historical materialism is an effective tool to grasp socio-economic relations, without necessarily conceding that it is material conditions—not God—that drive history. Notably, this is not too distant from many twentieth century broadly neo-Marxist re-readings and theorizations that critique vulgar material determinism.

Capitalism is essentially seen as constituting a problematic and unavoidable contemporary social reality. Fayyadl writes, “Once outside the mosque, if we shop at Indomaret [a store] or go to the bank, we are already unintentionally caught up in capitalism.” As a condition of reality, it is seen as having a “nature,” and Marxism is taken up as the authoritative science for its deconstruction—as grammar is to language, medicine to the body. As such, an understanding of Marxism actually becomes necessary to perform a proper Islamic legal analysis within the contemporary capitalist context. In one widely shared Facebook post, Fayyadl argued that students of Islamic boarding schools should be “committed to studying two books (kitab) simultaneously: “yellow books” (kitab kuning [Islamic texts]) and “red books” (kitab merah [Marxist literature]); adept at both the science of [Arabic] grammar (tata bahasa) (nahwu-sharaf) and the sciences of government (tata negara) and sociology (tata-masyarakat).”

By affirming Marxist social analysis and integrating it into traditionalist Islamic legal methodology—by deploying categories of “social benefit” and by treating Marxism as a “tool science” for understanding society—Fayyadl then opens the door to importing many of Marxism’s teachings and modes of analysis. For example, he argues that “materialist progressive Islam” must rely on class-based analysis. As we saw in the hypothetical case of Company A, Marxist expectations about how market domination by a large firm affects existing economic activity can then be taken as facts within jurisprudential reasoning.

Progressive Praxis

Ultimately, however, Fayyadl is not solely concerned with the theoretical realm of legal method. Rather, this thought constitutes the normative framework within which Fayyadl legitimizes Marxist social action. He asserts that progressive Islam must actively seek to not only deconstruct, but also “dismantle” the exploitative practices of capitalism. As such, progressive Muslims must engage in “continual organizing” within the existing class struggle.

Consequently, Fayyadl engages in activism in alliance with existing social movements that are often not articulated as particularly Islamic. For example, he has been a vocal advocate of a farmers’ movement in Kendeng, Central Java fighting a local cement factory. In 2013, he co-founded an organization called the “Nahdliyin Front for Popular Sovereignty over Natural Resources” (FNKSDA), to mobilize the NU community to act on issues of environmental destruction in agrarian and marine communities at the hands of the government and corporations. He also continues to teach in his family’s pesantren in East Java.

The novel potential of Fayyadl’s brand of Islamic socialism stems especially from his ability to push for progressive change from within the discursive structure of traditionalist Islamic scholarship. While articulating a “materialist” vision, Fayyadl remains committed to articulating Marxist critiques that are legible within the traditionalist fiqhi regime of reasoning. This framing seeks to open up a discursive space from within which Muslims committed to traditionalist epistemologies can be recruited to Marxism and the radical activism of the Left. In a country where the traditionalist NU is the most popular Islamic organization, and where children’s education in classical Islamic scholarship is widespread, this type of normative work may prove crucial.

[I would like to thank Muhammad Al-Fayyadl, Elham Mireshghi, Ahmed El Shamsy, and Ameena Yovan for their critical feedback on earlier drafts of this essay.]

Sawyer Martin French is a graduate student at the University of Chicago Divinity School. His research is in ethnography of Islamic thought and epistemology in Indonesia, focusing on public education, the academy, and social movements.