Since January 2016, I’ve been conducting ethnographic research on the progressive Muslim community globally, both face to face in six North American groups and in three online groups. Some of this work, which I report in distilled form in this essay, has been published in the Journal of Linguistic Anthropology, and I am currently working on a book manuscript tentatively titled “Misfits, Freaks, Rebels, and Queers: An Ethnography of Muslims on the Margins.” (The first part of the title is used with Michael Muhammad Knight’s permission, from a line in his excellent book Tripping with Allah.)

In this project, I use progressive Muslim as a catch-all term for individuals and communities committed to progressive reform and LGBTI inclusion. I’m aware that progressive is a contested term and that some of the people I write about prefer inclusive or other terms, and some want to avoid any kind of modifier. We’re just Muslims. I still haven’t found a term that everyone I spoke with likes, but for now I’m alternating between progressive, which allows me to connect to a significant body of research by like-minded Muslim academics like Omid Safi, Adis Duderija, and Kecia Ali, and nonconformist, a term I hope is more descriptive and avoids some of the terminological debates.

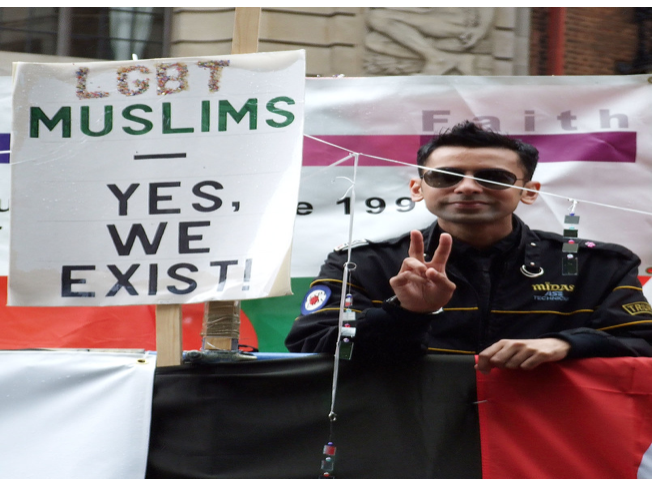

As a queer feminist and a progressive Muslim, I have a personal investment in this research. As LGBTI Muslims know all too well, despite the fact that 60 percent of U.S. Muslims support LGBT civil liberties, we are erased or silenced in most mosques and often in the LGBTI community as well. Unsurprisingly, it was precisely this erasure that led most of the LGBTI Muslims I interviewed to join progressive Muslim communities. What was perhaps surprising is that LGBTI-inclusion was also a central issue to the cisgender, heterosexual Muslims I spoke with.

“LGBTI Muslims involved in progressive Muslim groups contribute to what trans cultural studies scholar Jack Halberstam calls “a ‘queer’ adjustment”—an anti-normative adjustment in how we approach Islam.”

Among 32 interviewees, 26 explicitly addressed queerness in our conversations, and (by chance) they were evenly split: 13 identify as lesbian, gay, bisexual, trans, nonbinary, and/or queer, while the other 13 are straight, cisgender Muslims who nevertheless described LGBTI-inclusion as central to their experience of nonconformist groups. I argue, therefore, that LGBTI Muslims involved in progressive Muslim groups contribute to what trans cultural studies scholar Jack Halberstam calls “a ‘queer’ adjustment”—an anti-normative adjustment in how we approach Islam. In my analysis of my ethnographic observations and audio recordings, I focused not only the voices of participants who identify as LGBT, nonbinary, or queer but also on the stances of cisgender, heterosexual participants toward the inclusion of LGBTI Muslims in religious practices and, more broadly, toward what anthropologist George Meiu calls “queer moments” within those religious practices. I argue that acceptance of LGBTI Muslims pushes even cisgender, heterosexual progressive Muslims to a marginalized position in relation to Islamic gender and sexual norms; in this sense, they become “queer”—different, nonnormative, deviant, subversive, transgressive—even though they’re not LGBTI.

“Acceptance of LGBTI Muslims pushes even cisgender, heterosexual progressive Muslims to a marginalized position in relation to Islamic gender and sexual norms.”

Uttering Islamic Words with a Queer Mouth

I’ll give just two examples from my interviews, both from Canadian women, focused on how LGBTI Muslims and allies use language strategically to make space for nonconformity. In October 2016, I spoke with Mouna (a pseudonym), a Canadian lesbian in her late thirties, of South Asian descent, who was raised Muslim in Toronto and still lives there. I asked her if there are particular words or concepts in the Qur’an that she has found problematic or troublesome as a queer Muslim or as a progressive Muslim. In her response, Mouna presented herself as resistant not to the Qur’an but rather to the ways that LGBT Muslims have been excluded from Islam. She spoke about “the idea of resistance” and “taking back” language that has been used in violent ways. She told me, “In some spaces, I identify myself as queer because I wanna take that back. I wanna take back dyke, I wanna take back lesbian, I wanna take these things back.” Openly naming herself as both queer, a dyke, or lesbian and Muslim resists others’ excluding her from these identity categories.

Mouna went on to describe how using Arabic words for Islamic concepts is also a means of resistance, a signifier of her authenticity as a Muslim: Using the word tawhid as an example, she said, “I wanna say it in Arabic because people question my authenticity as a Muslim because of me identifying as lesbian, queer, whatever. And so I want those words uttered by a queer mouth that are uttered by heterosexual people everywhere.” In some contexts, Arabic terms like tawhid may function to authenticate one’s Muslimness. But here it is also a response to others’ denaturalizing the relationship between Muslimness and queerness. While others may see these identities as incompatible, Mouna juxtaposes them through language to insist that they are compatible. As Mouna suggests, when a queer Muslim uses Arabic words for Islamic concepts, the words themselves are queered, or given a queer “voice.” By using both Arabic words that mark her as a Muslim and refusing to be silent about her queerness, Mouna uses combinations of categories that challenge dominant understandings of both Muslimness and queerness.

Whereas for many Muslims, Arabic has high prestige value, Mouna made clear in our conversation that Arabic does not hold the same prestige for her, and she critiqued the imposition of some elements of Arab culture on non-Arab Muslims, such as wearing an abaya rather than the clothing of one’s own culture. Rather, Arabic terms for Islamic concepts like tawhid function as both authentication and resistance to others’ attempts to erase LGBT Muslims. By rhetorically linking queerness and religious Arabic but making a distinction between Arabic and Arabs, Mouna was able to index a stance as a ‘good’ Muslim without denying or negating other aspects of her identity.

Straight Queering of Muslim Discourse

My second example, from an interview with Stephanie, shows how cisgender, heterosexual progressive Muslims can also resist LGBT Muslim erasure by “queering” hegemonic discourse. Stephanie describes herself as a “white girl” who converted to Islam in her mid-twenties and had studied Islam for about three years before that. She has gay fathers, and says she was raised both in the LGBT community and the Catholic church. Stephanie depicted her involvement with her local progressive Muslim group as focused on “community bridging”—entering conservative Muslim spaces and inviting attendees to the progressive Muslim group in Ottawa which she is involved. She told me that being white, cisgender, and heterosexual gave her “a lot of privilege … in conservative circles.” She likes to show up at convert events and say, “Yeah, I’m a Muslim convert and I converted after I realized that there are progressive Muslims who believe LGBTQ people are okay.” This “totally derails everybody else and it’s great and I love it,” she told me.

Convert events like those Stephanie mentions often begin with a time for “convert stories” about how one became Muslim. Here Stephanie up-ends the genre by describing not how she became Muslim but rather how she became a progressive Muslim. By doing this, she contrasts progressive Muslim support for LGBTI equality with the conservative norms taught in convert circles and enacts her own queer daw’ah by inviting others to her progressive Muslim group. Stephanie used the word fitna to proudly describe her effect on conservative groups. Like Mouna, Stephanie uses a “queer voice” in reclaiming the word fitna, a concept often associated with women. Here it also alludes to the Facebook group, FITNA (an acronym for Feminist Islamic Thinkers of North America). Stephanie’s use of the Arabic word fitna points to her Muslimness, but, like FITNA’s founders, she resignifies the word, evaluating it positively. By derailing conversations in conservative circles, disrupting normative worldviews, and—as she puts it—“causing shit,” Stephanie uses her white, cisgender, heterosexual privilege to queer the Muslim spaces she enters by putting both genres and words to new uses, with the aim of advancing LGBT-inclusivity within Islam.

When “uttered by a queer mouth,” practiced by a queer body, or ‘queered’ in other ways by even cishet progressive Muslims, religious language or engaging in religious practices might point not to traditional piety but rather to multiple identity categories simultaneously. Queer Muslim talk allows LGBT Muslims to claim both Muslimness and queerness simultaneously, in ways previously foreclosed in other Muslim and non-Muslim LGBT communities.

“Queer Muslim talk allows LGBT Muslims to claim both Muslimness and queerness simultaneously, in ways previously foreclosed in other Muslim and non-Muslim LGBT communities.”

Conclusion

In the original version of this article, I also look at how we queer our religious practices. In progressive congregational prayer, LGBTI Muslims’ participation in roles normally reserved for cisgender, heterosexual men (giving the call to prayer, giving a khutbah, or leading prayer) effectively queers these rituals not just for us but for our allies as well. By departing from the normative practice of passive sermon listening, through the encouragement of discussion before, during, or after a sermon, progressive Muslim congregations welcome the voices and perspectives of LGBTI Muslims and effectively “queer” the talk of everyone who attends.