The image of the voracious reader in prison is a powerful trope of film and literature, from The Shawshank Redemption to the Autobiography of Malcolm X. Based on the idea of redemption through education, it is a hopeful image that one can use their time in prison to grow, nurtured by the positive influences of classic literature and religious texts. This image is not entirely false; numerous formerly-incarcerated people cite books and education as a source of moral development in their prison journeys. Yet this trope often presupposes a rather prescriptive and narrow vision of the “right” kind of literature and religious growth. One likely does not imagine James Patterson, a best-selling non-fiction and romance novelist, being a source of salvation to a person spending decades or life in prison. However, one need only think of Hannibal Lecter to recall that sometimes, classic literature is not a good influence.

“Because access to books is controlled by the prison system, religious groups, and groups that rely on donated materials, incarcerated Muslims lose the agency to find meaningful spiritual books if their interests are deemed ‘unsuitable.'”

Despite this trope, access to books is severely limited in contemporary American prisons. At the federal, state, county, and city level, books face strict regulations before they can enter a prison. Moreover, incarcerated Muslims seeking to find respite, betterment, or intellectual challenge in religious books face numerous barriers beyond the usual restrictions. The limited access to Islamic books is linked to the wider assumptions about redemption in prison being rooted in Protestant Christianity. Because access to books is controlled by the state prison system, religious groups, and groups that rely on donated materials, incarcerated Muslims lose the agency to find meaningful spiritual books if their interests are deemed “unsuitable.”

This article begins by outlining how the anxieties surrounding Islam in prison settings impacts the availability of Islamic religious programming broadly before examining how such bias impacts access to Islamic texts. To establish bias, I draw on the ethnographic research of Tanya Erzen and Joshua Dubler. When discussing books, I focus on the prisons’ library resources, a list of available e-books, and the efforts of free books-to-prisoners groups in Pennsylvania. I selected Pennsylvania for two reasons: first, in 2018, Pennsylvania barred free books-to-prisoners groups from sending reading materials. While the ban was reversed, it highlighted the precarity of access to books and offered a disturbing glimpse into what texts the Department of Corrections (DOC) would provide if granted full control of prisoners’ reading. Second, I have been involved with Books Through Bars, the state’s largest free books-to-prisoners group, for five years, which allowed me access to the group’s archival materials. Though this paper focuses on Pennsylvania, the trends are mirrored nationally, and in some states, they are even more severe.

Inequalities in Spiritual Programming and Their Effects on Incarcerated Muslims

While the cliché that “everyone finds religion in prison” may have some truth to it, the institutional resources for all religions are not equal, nor is the perceived merit of each religion. The notion of rehabilitation in the American prison system is rooted in Quaker and Methodist notions of penitence and solitary self-reflection, leading to a space in which “religious redemption has been uneasily, but inextricably tied to punishment.”[1] Tanya Erzen’s pioneering work God in Captivity documents the recent rise and increasing institutional support of Christian faith-based programs in prisons. The overwhelming success of such programs is shown in Erzen’s observation that, “in many states, non-denominational Protestant Christians make up more than 85% of the volunteers who enter a prison.”[2] Though at times, these programs are billed simply as “Faith-based,” Erzen argues that “‘faith’ is more or less equivalent with “Christian,” and states that when Christian spiritual resources are the only ones available, “a wide range of people are excluded from redemption.”[3]

“In such a system, incarcerated Muslims face limited access to chaplains, spiritual fellowship from outside volunteers, and often must legally negotiate for their religious rights that do not directly align with Protestant-style practice.”

In such a system, incarcerated Muslims face limited access to chaplains, spiritual fellowship from outside volunteers, and often must legally negotiate for their religious rights that do not directly align with Protestant-style practice. There are numerous documented cases of incarcerated Muslims having to file lawsuits to allow for basic religious practices, including proper suhoor meals during Ramadan and wearing hijabs in official photographs. A 2012 Pew Survey of prison chaplains noted that Muslims account for approximately 9 percent of the prison population and are the most consistently “underserved” by volunteers. Volunteers in faith-based groups provide a variety of functions, including conducting jummah prayers, leading Qurʾan study groups or more general religious-enrichment meetings. Though institutional rules vary, at one major Pennsylvania prison, a chaplain or volunteer must be present for formal worship or religious enrichment classes. If a volunteer is unable to visit on a given day, services and classes are cancelled.[4] In Joshua Dubler’s seminal study of religion in Pennsylvania’s Graterford Prison Down in the Chapel, incarcerated Muslims argued they would have “no trouble finding a volunteer-led Protestant Bible study every day of the week,” but programming for Muslims was much more sparse.[5]

There is a variety of reasons for a shortage of Muslim volunteers, but this disparity in programming leads to a perception among incarcerated Muslims that they are the subject of discrimination. The location of many state prisons presents a difficulty for Muslim volunteers as the majority of American Muslims live in urban centers, but many state prisons are in rural areas.[6] Second, when considering America’s disproportionate incarceration rates for African Americans, black Muslims can face an additional hurdle to volunteering. When discussing Graterford Prison, located about 30 miles outside of Philadelphia, Dubler notes that, “many who might be interested in volunteering couldn’t pass the background check, either because of their own criminal histories or because of known associations with one or another Graterford resident.”[7] This case also highlights the fact that incarcerated Muslims perceive this limited programming as discrimination, particularly when contrasted to institutional views of Christianity. While the chaplain argues that he’s “issued many invitations, but that no one answers the call,” the prison’s Muslim population believes their chaplain could do more to recruit volunteers.[8] In both Erzen and Dubler’s studies, it is clear that many incarcerated Muslims believe that Christian groups receive preferential treatment.

Further compounding the perceived inequality, prison officials tend to view Islam either neutrally or suspiciously, in contrast to the institutional support Christian faith-based organizations receive. Erzen gives an example of a debate over what brought “peace and order” to the famously troubled prison of Angola in Louisiana. Prison officials credited the Christian seminary prison for this change; however, the incarcerated Muslims argued that the rise of conversion to the Nation of Islam in the 1970s was the true turning point. According to Norris Henderson, who was incarcerated at Angola and now leads jummah services as a volunteer, “It happened with the black power movement, the Nation, and the idea that they were their brother’s keeper.”[9] He argues that the Nation’s advocacy helped all prisoners to have improved living conditions, advocacy, and legal rights.[10] Following broader national trends, Erzen demonstrates that as “one of the original faith-based organizations in prison,” the Nation fought numerous legal battles to improve prison conditions, including education and violence-prevention efforts.[11] These examples highlight that prison officials may be reluctant to see positive value in Islam. First, they show a reluctance to acknowledge the positive contributions of Muslim faith-based efforts in prison. Moreover, the view of the Nation of Islam as a radical, dangerous movement seems to affect the image of all prison-related Islamic activities as radical or untrustworthy.

While anxieties about the black power movement prevailed in the 1970s, today misgivings about Muslim prison ministry are typically rooted in a suspicion of terrorism or extremism. In one example, Erzen describes an incarcerated Muslim in Texas who tried to start a Qurʾan study group, but prison officials shut the group down. Frustrated, he argued that “they think its terrorism…if this was a Christian group, it would be fine.”[12] The 2012 Pew Survey shows that this concern is shared by prison chaplains, who report that Muslim groups were the most likely to have “extreme” views, particularly if they were members of Afrocentric forms of Islam, such as the Nation of Islam or the Moorish Science Temple of America. Furthermore, as Joshua Dubler notes, American prisons have significant rates of Muslims who identify as Salafi, a conservative form of Islam. While Salafism at its core advocates living one’s life as closely as possible to the ideals of Muhammad and his Companions, because a number of historical incidents of terrorism were linked to proponents of Salafi Islam, many associate it with terrorism. While prison officials should rightly curtail any efforts to cultivate terrorism, Salafi Islam itself is not equivalent to terrorism. Prison officials should certainly do everything within their power to limit access to terrorist propaganda and messaging. However, literature produced by Salafis should be understood first as religiously conservative, and not, by nature, terroristic. Salafi works could be viewed as akin to conservative Christian materials, which are prevalent in prison environments with no notice or censure from prison authorities.

Prison Library Resources and Barriers to Accessing Islamic Books

Given the general issues surrounding the practice of Islam in prison, it is perhaps unsurprising that Muslims seem to face additional hurdles in accessing religious books. Indeed, all incarcerated people have limited access to books, with all book choices having to be approved by the prison. Incarcerated people can get books from facility libraries, chapel collections, or through approved vendors. Federal regulations prevent friends and family members sending books directly. While some prisons allow individuals and congregations to donate to library chapel collections, this is not a universal practice, leading to collections in non-Christian religions being sparse and cultivated by non-practitioners. The option to order books directly from Amazon or another approved vendor is often cost-prohibitive, so many incarcerated people turn to free books-to-prisoners groups.

Beginning with the resources provided by the state, it is difficult to know what religious books the Pennsylvania DOC provides to incarcerated people, but publicly available information displays a lack of care towards Islamic spiritual life at best and hostile Islamophobia at worst. The DOC controls general libraries, chapel libraries, and an e-reader list. The e-reader list is publicly available, whereas information about State Correctional Institution (SCI) libraries and chapel libraries is not. Throughout the period of the ban on free books to prisons in 2018, the DOC emphasized that e-books were just one way that incarcerated people could access reading materials. In a newspaper interview during the book ban, Amy Worden, a DOC spokesperson, noted, “Lost in this discussion of e-books and book donations is the fact EVERY prison has a full service general interest library and a law library.” However, the DOC did not respond to multiple requests for information about prison libraries and their holdings. Moreover, currently and formerly incarcerated Pennsylvanians cite myriad reasons why the facility libraries are inaccessible or undesirable. In a striking example, one man said “at the Camp Hill state prison, he received 45 days in-cell confinement for returning a book late; he promised himself never to risk borrowing from the library again.”

One can infer a similar situation regarding Pennsylvania State Prison chapel books. The head of chaplaincy in Pennsylvania SCIs did not respond to multiple requests for comments on chapel books. Based on other studies of chapel books, they are mostly donated and “represent the eclectic nature of the donor rather than a systemized collection.”[13] Because the majority of chaplains and religious volunteers (who often contribute to chapel collections) are Christian, this may lead to collections that focus on Christian spirituality. Furthermore, collections are curated by the chaplains; while incarcerated people may request specific books, a chaplain’s determination on the suitability of a book may be highly subjective.

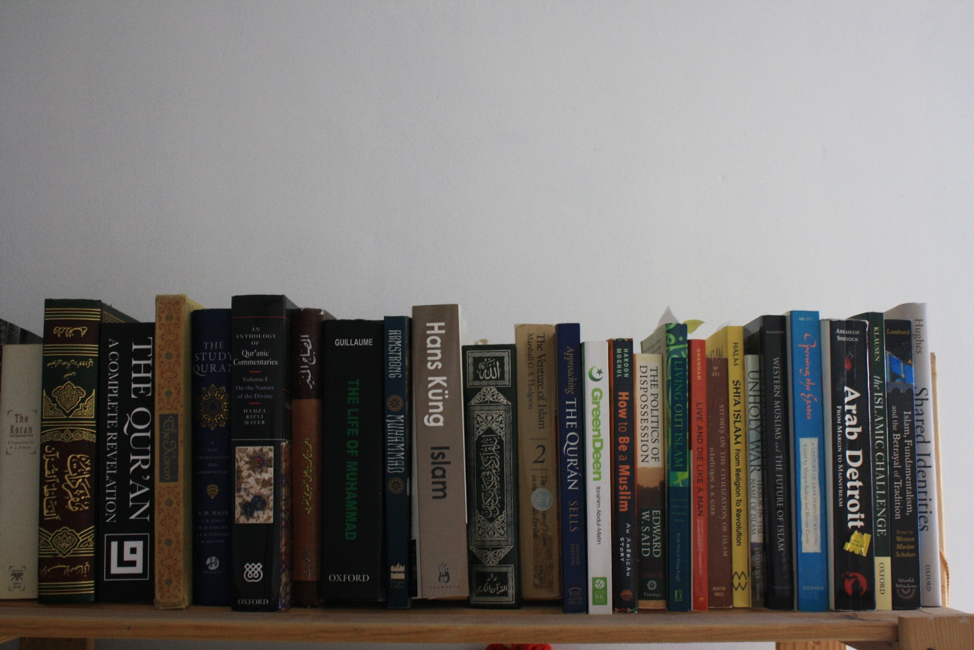

Given the lack of response from the DOC on their library holdings, the e-book list gives the only conclusive information of what books the DOC provides for incarcerated Muslims. The list reveals that under state control, reading material on Islam is selected with little care for the needs or desires of practicing Muslims. Provided by GTL, a private corrections technology company, approximately 8,500 books are available for purchase. Of these, there are only ten books available related to Islam. The list does not include an Arabic Qurʾan, and the only translation available is by J.M. Rodwell in which the suras are not in standard order. In contrast, the Bible offered is the King James Version and the list also offers a Spanish translation. The list contains only one other primary Islamic source: The Improvement of Human Reason by the medieval philosopher Ibn Ṭufayl. Notably absent are hadith collections, sira literature, or any texts related to the Nation of Islam. The omission of such texts could indicate a suspicion regarding the redemptive potential of Islam, and specific distrust of Afrocentric forms of Islam. Of the seven secondary sources on Islam, five were written before 1930 and have an explicitly anti-Muslim bias. Perhaps the most egregious example is the inclusion of The New World of Islam, by Lothrop Stoddard, a eugenicist and Klu Klux Klan member. The list has two recent scholarly works on Islam (Memories of Muhammad, by Omid Safi and Muhammad, by Karen Armstrong), but these works are sold at prohibitively expensive prices. There is one Islamic novel on the list. Though not exhaustive, the list’s holdings in Christianity reflect a broad range of topics and genres, and no explicitly anti-Christian materials.

To supplement these insufficient resources, incarcerated Muslims frequently turn to Muslim organizations for reading materials. Muslim non-profits and mosques will often work to provide books for incarcerated Muslims. For example, the Council on American-Islamic Relations, the Prison Qurʾan Project, and Masjid al-Rabia (an LGBTQ Muslim group), have all made efforts to send free Qurʾans to incarcerated Muslims. Individual mosques and Muslim chaplains also receive book requests from incarcerated Muslims. While these efforts are necessary and provide much relief, some of these groups may consciously or unconsciously impose their own theological understandings of Islam on those who are incarcerated. For example, perhaps because conservative Islam is viewed as being connected to terrorism, some mosques are reluctant to send Salafi materials. A chaplain who serves a Pennsylvania county jail noted that despite the high volume of requests, the local mosque would not send The Noble Qurʾān translation or other materials with a Salafi orientation, because it did not reflect their values.[14] He said that if an incarcerated person insists on that translation, he will provide it, but as an individual, not a representative of the mosque. It is certainly understandable for a mosque or group to choose not to send materials that conflict with their values or approach to Islam. However, with the current book restrictions in the prison system, such a decision essentially denies agency to the incarcerated Muslim by limiting them to material selected by a congregation or chaplain.

In addition to reaching out to mosques, many incarcerated Muslims rely on free books-to-prisoners programs to supplement their reading materials. Books-to-prisoners groups are considered approved vendors by most states, though this was challenged in recent legal battles in Pennsylvania and Washington. Pennsylvania is home to two free books-to-prisoners groups (Books Through Bars in Philadelphia and Book ‘Em in Pittsburgh), and there are dozens of others around the country. The astonishing number of requests to books-to-prisoners groups reveals limitations of state-provided literary resources in American prisons. Books Through Bars (BTB) receives approximately 8,000 book requests every year and is able to send approximately 700 packages per month. Book ‘Em sends approximately 160 packages per month. Though each organization varies in its approach, books-to-prisoners groups typically operate like libraries, with open access to information and the belief that “those on the inside know best what they need.” Regarding religion, this policy means that these groups will send religious books as requested, with no theological investment in the question of “what is the proper way to be Muslim?”

Books-to-prisoners groups not only provide books, but as restorative justice activist aems emswiler argues, they serve as a “counter archive” with the potential to reveal a richer narrative about the lives of incarcerated people than that of the prison’s “official” records. Such an archive provides primary source access to the lives of incarcerated people, in direct contrast to the media or official prison narratives. Exploring these resources “humanizes a population of people seen as inhuman, criminal, and homogenous,” and has the power to help scholars and the general public “understand incarceration, and people most impacted by state violence.” And while there are many questions regarding the ethics of such an archive, emswiler notes the importance of books-to-prisoners groups centering their management of archival materials in “accountability, security, safety and collaboration.”[15] For the purposes of this article, these archives reveal the specific reading requests of those incarcerated in the mid-Atlantic region. BTB’s counter archive reveals deeply thoughtful religious engagement and consciously selected book choices.

Following emswiler’s insight, part of this project included analysis of a small sample of BTB’s archival data, which reveals that Muslims typically request foundational texts, while their Christian counterparts tend to be much more specialized. This suggests that incarcerated Christians’ most basic reading needs are met by institutional resources. In a survey of 219 letters to BTB that requested religious materials, about 20 percent asked for books on Islam, 32 percent for Christianity, and 48 percent for all other religions.[16] Of other religions, the most frequently represented are Wicca and Neo-Pagan traditions. In letters requesting books on Islam, the most frequent requests were for the Qurʾan or something more general (such as “Islamic books”). Frequently-requested titles such as The Sealed Nectar, When the Moon Split, and the Noble Qurʾan translation generally reflect a Salafi orientation. There was also a trend showing a sustained interest in the Nation of Islam, Five Percenters, and other Afrocentric forms of Islam. However, 40 percent of requests simply asked for the Qurʾan, suggesting that many incarcerated Muslims do not have a Qurʾan of their own. In contrast, letters requesting Christian materials asked for more specialized texts, such as Bible concordances, and fiction; only 7 percent asked for a Bible. When comparing these requests with the GTL e-book list, it becomes clear that the GTL did not conduct a systematic survey on the reading needs of incarcerated Pennsylvanians or possibly intentionally curated a list to discourage interest in Islam.

“…40 percent of requests simply asked for the Qurʾan, suggesting that many incarcerated Muslims do not have a Qurʾan of their own. In contrast, letters requesting Christian materials asked for more specialized texts, such as Bible concordances, and fiction; only 7 percent asked for a Bible.”

While books-to-prisoners groups do not have the same theological commitments or anxieties of religiously-affiliated groups or the DOC, their reliance upon donated materials can unintentionally reinforce a lack of agency in selecting book titles. It is important to note that both BTB and Book ‘Em can seldom send specific titles for any request. However, the extent of their collections in specific religious literature is often tied to congregational donations. These materials thus reflect the values of the particular congregations or individuals who choose to donate materials. An anonymous representative from BTB reports that the group’s library is generally well-stocked in Christian and Jewish books thanks to donations from churches and synagogues. The groups gets Islamic materials from individual donors and “a few men from local mosques who have offered to replenish the supply of Korans on a semi-regular basis.”[17] Book ‘Em’s general religious holdings mirror BTB’s, but representative Jodi Lincoln said the group has a relationship with one donor who has greatly expanded their holdings in Islam. In e-mail correspondence, Lincoln writes that the donor “regularly purchases new Islamic books and Quran’s for us!”[18] This donor also helps to fill previously lacking areas like hadith literature. She notes that because of him, the group can typically send something to individuals requesting Islamic books. Both representatives noted they could not provide specific translations of the Qurʾan or specific titles. Because books-to-prisoners groups collections are in constant flux, reflecting the libraries of their donors (whether personal or congregational), even without a conscious effort to promote a specific type of Islam or undermine another, this may happen involuntarily due to the resources on hand.

Conclusion

“Though a meaningful spiritual life is not limited to reading materials or interactions with chaplains, the trend of limited access to Islamic texts reveals the way in which incarcerated Muslims face challenges in cultivating the religious lives they desire.”

Though a meaningful spiritual life is not limited to reading materials or interactions with chaplains, the trend of limited access to Islamic texts reveals the way in which incarcerated Muslims face challenges in cultivating the religious lives they desire. While it is possible that Pennsylvania’s SCI libraries and chapel libraries are providing excellent spiritual resources to incarcerated Muslims, the requests to books-to-prisoners groups, mosques, and the reports of formerly incarcerated Muslims indicate otherwise. This lack of access fits into the broader trend of viewing Islam with suspicion rather than as a positive, redemptive force for those who are incarcerated. By having to prove the “suitability” of their interest in religious texts, incarcerated Muslims lose an additional piece of agency in their lives. Exposing these challenges is only the beginning; considerably more study of Islam in prison is necessary. Doing so adds much-needed diversity in the academic study of religion in prison. Finally, such studies promise to demonstrate the rich and nuanced religious lives of incarcerated Muslims to counter overly simplistic narratives of prison Islam as “radical” or dangerous.

Rebecca Makas is an Assistant Professor in the Augustine and Culture Seminar Program at Villanova University. Her research focuses on the intersection of mysticism and philosophy in medieval Islam. This piece reflects an emerging aspect of her research: religion and incarceration. She is the author of “Is Esoteric Islamic Spirituality Mysticism? Sufism, Ishrāqī Philosophy, and the Limitations of Religious Studies Theories” in Pakistan Journal of Historical Studies (forthcoming) and is currently working on a book project about the role of ineffability in Islamic mystical epistemology.

Top image: SCI Phoenix in Pennsylvania. Source: https://www.inquirer.com/news/sci-phoenix-graterford-pennsylvania-prison-incarceration-wetzel-wolf-20190122.html

[1] Tanya Erzen, God in Captivity: The Rise of Faith-Based Prison Ministries in the Age of Mass Incarceration (Boston: Beacon Press, 2017), 10.

[2] Erzen, God in Captivity, 4.

[3] Erzen, 5-6.

[4] Joshua Dubler, Down In the Chapel: Religious Life in An American Prison (New York: Farrar, Straus and Giroux, 2013), xv-xvi.

[5] Dubler, 207.

[6] Erzen. God in Captivity, 91.

[7] In 2018, Graterford Prison closed and all incarnated people who resided there were moved to nearby SCI Phoenix.

[8] Dubler, Down In the Chapel, 207.

[9] Erzen, God in Captivity, 101.

[10] Erzen, 101.

[11] Erzen, 102-105.

[12] Erzen, 100.

[13] Erzen, 91.

[14] Interview with anonymous prison chaplain, July 8, 2019.

[15] aems emswiler. “Books to Prisoner’s Programs as Alternative Archives,” Prison Abolition Work Panel, Books to Prisoners National Conference, Boston 2019.

[16] This data is from letters from the mid-Atlantic region of the US (Delaware, Pennsylvania, New Jersey, New York, Maryland, Virginia, and West Virginia). Though BTB receives letters from all 50 states, it only fills requests to the mid-Atlantic region.

[17] Anonymous BTB representative, interview with author e-mail correspondence, 10/29/2019

[18] Jodi Lincoln (Book ‘Em volunteer), interview with author e-mail correspondence, 10/25/19.