In the era of the Coronavirus, it would be prudent to look at other times of pandemics and how they impacted society and daily living. The so-called “Black Death” was one of the worst plagues in human history, with some estimates stating it wiped out 50 percent of Europe’s population.[1] The plague peaked between the years 1348-50 but reemerged on and off throughout the pre-modern period. Much of the work on the plague has focused on Europe but the pandemic had disastrous effects on the Middle East as well as other parts of the world.[2]

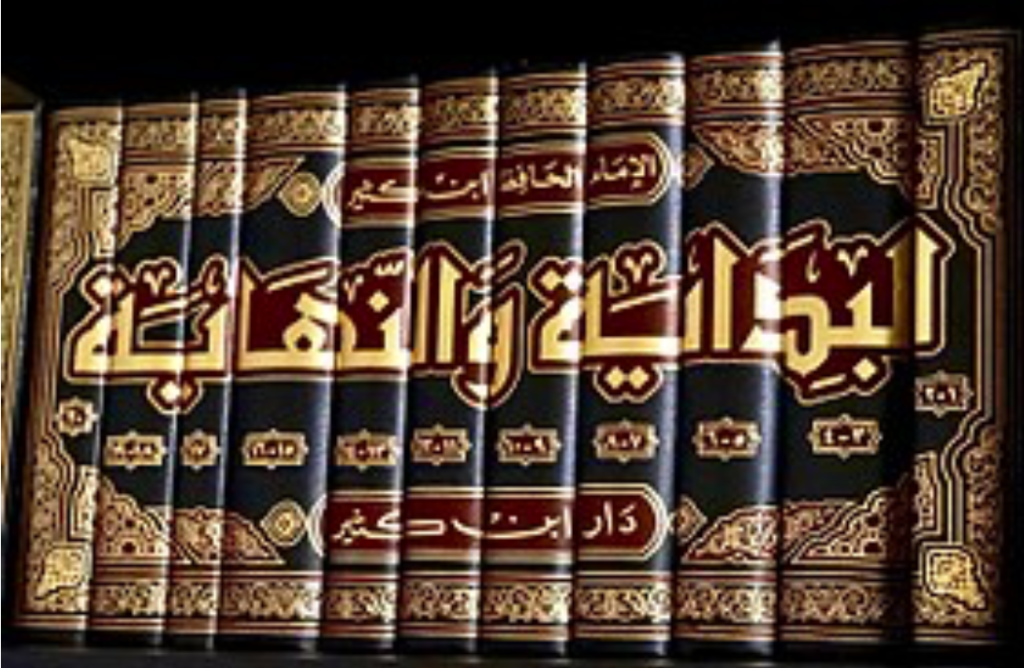

“The famous historian and Qur’anic exegete Ibn Kathīr (d. 774/1373) records the effects of the Black Death in his hometown of Damascus in his historical chronicle ‘The Beginning and the End’ (al-Bidāya wa’l-Nihāya).[3] The chronicle is a universal history starting with the beginning of human creation and continuing up until Ibn Kathīr’s own lifetime. Most of the text consists of Ibn Kathīr analyzing and summarizing older histories but the last volume is arguably the most interesting as it includes his personal observations and eye witnessing of contemporary events.”

The famous historian and Qur’anic exegete Ibn Kathīr (d. 774/1373) records the effects of the Black Death in his hometown of Damascus in his historical chronicle “The Beginning and the End” (al-Bidāya wa’l-Nihāya).[3] The chronical is a universal history starting with the beginning of human creation and continuing up until Ibn Kathīr’s own lifetime. Most of the text consists of Ibn Kathīr analyzing and summarizing older histories but the last volume is arguably the most interesting as it includes his personal observations and eye witnessing of contemporary events.

Panic in Damascus

In the year 749/1348-49, Ibn Kathīr describes how the plague was impacting Damascus and the panic that it caused.[4] On Friday June 5th, 1348 (Rabī‘ al-Awwal 7th, 749), Ibn Kathīr notes that after the congregational prayer (jum‘a) the judges and a group of people attended a public recitation of the famous hadith collection of al-Bukhārī (d. 256/870) and prayed that God would lift the plague from the land.[5] The plague’s emergence had been reported in the outskirts of the city and in the region in general and the people feared that it would descend on Damascus. Two days later, people gathered at the Miḥrāb al-Ṣaḥāba, one of the original prayer niches of the grand Umayyad mosque,[6] and recited among themselves the Qur’anic chapter of Noah/Nūḥ 3,336 times based on a dream a man reportedly saw in which the Prophet instructed him to read the chapter that number of times.

As the plague spread, the deaths dramatically increased – first 100 per day, then 200 and peaking at 300.[7] Ibn Kathīr explains that the deaths were so much that a household would try to remove their dead but then the majority of them would eventually die (and thus be unable to complete the task of burial). On Monday, July 14th (Rabī‘ al-Thānī 16th), a little more than a month after the plague’s first appearance in the city, local authorities called for an extra supplication in each daily prayer (qunūt) asking God to raise the plague from the land. People began to surrender themselves to God, submit to Him, supplicate, implore, and seek repentance. Throughout Ibn Kathīr’s description he constantly invokes the Qur’anic phrase (2:156) “To God we belong, and to him we return” (Innā li-Allāh wa innā ‘ilayhi rāji‘ūn) which is typically said after a death or great calamity.

“A Memorable Day”

One particular event demonstrates how the plague was uniting the city and creating a unified sense of spirituality.[8] On Monday, July 21st, 1348 (Rabī‘ al-Thānī 23rd, 749) a call was made that the city’s inhabitants should fast three days and that they should come out on Friday and implore God to raise the plague from their city. For the following three days, most of the people fasted and some slept in mosques, spending the night praying as they do in the month of Ramadan.

“On Monday, July 21st, 1348 (Rabī‘ al-Thānī 23rd, 749) a call was made that the city’s inhabitants should fast three days and that they should come out on Friday and implore God to raise the plague from their city. For the following three days, most of the people fasted and some slept in mosques, spending the night praying as they do in the month of Ramadan.”

On Friday, the city’s inhabitants flocked to the mosque, emerging, as it were, “from every deep mountain pass,” a Qur’anic reference to the Hajj (verse 22:27). The crowd encompassed the entire population of Damascus – the Jews, Christians, Samaritans, elderly, children, poor, rulers, notables and judges. All came after the early Morning Prayer and made their way to the “Mosque of the Foot” south of the city. According to the famous Ibn Baṭṭūṭa (d. 770/1368-9 or 779/1377) the “Mosque of the Foot” or “Feet” was named after traces of footsteps left in stone that were ascribed to Moses/Mūsā with some believing that his grave was near the mosque based on a dream of the Prophet Muhammad. The mosque thus served as an interfaith site and a place where the various members of the population could gather around. At the mosque, the city’s inhabitants called on God until daybreak or midday. Ibn Kathīr ends his observation stating that “it was memorable day” (yawm mashhūd).

Ibn Baṭṭūṭa was also an eyewitness to the event and records it within in his famous Travels devoting a special section to the day.[9] Ibn Baṭṭūṭa additionally emphasizes the sense of equality felt within the gathering, stating that on Thursday night “the rulers, notables, judges and all different (social) classes gathered in the (Umayyad) mosque until they became crowded and they stayed the whole night. Among them were people who were praying, remembering (God), and calling out (to Him).” After the Morning Prayer, they all left together on foot and in their hands were Qur’ans (al-maṣāḥif). Ibn Batṭūṭa observes that the rulers were barefoot and all of the inhabitants of the city came out, “men and women, children and the elderly.” Among them were the “Jews with their Torahs and the Christians with their Gospels.” Everyone was crying, imploring and seeking intercession with God’s Books and Prophets. Ibn Baṭṭūṭa notes that after the event, God decreased the number of deaths in the city compared to others such as Cairo.[10]

From this observation, we see that the Muslims began to go back to the essentials of their faith by praying and emulating certain practices only done in Ramadan, such as spending the entire night in prayer. Ibn Kathīr references Hajj and the practice of praying together in large crowds as reminiscent of the ritual’s Day of Arafat. Moreover, the plague was uniting the diverse Damascus population against a common threat. The various religious groups were coming together and even praying in a similar place as the plague did not discriminate against anyone. The inclusion of Jews is remarkable because in Europe they were often used as scapegoats and blamed for the plague’s outbreak.[11] Ibn Kathīr and Ibn Baṭṭūṭa also make sure to emphasize how the entire populate emerged that day – the poor and the rich, the weak and the powerful – suggesting that such an occurrence did not happen otherwise. A certain equality had developed with the population realizing that everyone was vulnerable.[12]

“Ibn Battuta observes that the rulers were barefoot and all of the inhabitants of the city came out, ‘men and women, children and the elderly.’ Among them were the ‘Jews with their Torahs and the Christians with their Gospels.’ Everyone was crying, imploring and seeking intercession with God’s Books and Prophets. Ibn Battuta notes that after the event, God decreased the number of deaths in the city compared to others such as Cairo.[10]”

Conclusion

In summary, analyzing these historical chronicles helps us realize that plagues were common occurrence throughout human history and that it had both emotional and physical impacts on a population. The various communal responses demonstrate ways that people found solace in faith, scripture and one another. While the inhabitants had their differences, the Black Death united them in their various social classes and religious traditions. No one seemed to be scapegoated with everyone realizing that they were vulnerable and prone to the disease. Their united front allowed them to eventually move beyond the plague and to remake their lives once again.

Dr. Younus Y. Mirza is a Visiting Researcher at Georgetown University and Director of the Barzinji Project at Shenandoah University which seeks to enhance America’s relationship with Muslim-majority countries. To learn more about his scholarship, teaching, consulting and speaking, please visit his website http://dryounusmirza.com

*Top Image: The Grand Umayyad Mosque of Damascus was the most important mosque in the city and a key place of learning and study. On the night of Thursday, July 24th, 1348, many of the city’s inhabitants gathered here to pray for the end of the plague.

[1] John Aberth, The Black Death: the Great Mortality of 1348-1350: a Brief History with Documents (New York: Palgrave Macmillan, 2005), 3.

[2] Michael Dols, The Black Death in the Middle East (Princeton, N.J.: Princeton University Press, 1977). Dols’ work remains the most authoritative work on the Black Death in the region.

[3] For more on the life and works of Ibn Kathīr see Younus Y. Mirza, “Ibn Kathīr, ʿImād al-Dīn”, in Encyclopaedia of Islam, THREE, eds. Kate Fleet, Gudrun Krämer, Denis Matringe, John Nawas, and Everett Rowson (Leiden: Boston: Brill 2016).

[4] Ibn Kathīr, al-Bidāya wa’l-nihāya, ed. Ḥasan Ismā‘īl Marwa (Damascus: Dār Ibn Kathīr, 2009), 16:41.

[5] For more on the public reading of al-Bukhārī see Jonathan Brown, The Canonization of al-Bukhārī and Muslim: the Formation and Function of the Sunnī Ḥadīth Canon (Leiden: Brill, 2007), 338; Joel Blecher, Said the Prophet of God: Hadith Commentary Across a Millennium (Oakland, California: University of California Press, 2018).

[6] Alī al-Ṭanṭāwī, Jāmi’ al-Umawī (Jedda: Dār al-Manāra, 1991), 27.

[7] Ibn Kathīr, 16:42.

[8] This passage is translated in John Aberth, 110. However, while the translation is generally very good there are some minor mistakes. For instance, the author translates a passage by stating that “On the morning of June 7, the crowd reassembled before the mihrab of the Companions of the Prophet, and it resumed the recitation of the flood of Noah, of which a reading was made 3,363 times, in accordance with the counsel of a man to who the Prophet had appeared in song and had suggested this prayer.” The translation should read, “On the morning of June 7th of the same month, the crowd gathered at the mihrab of the Companions (of the Prophet), and they recited among themselves the (Qur’anic) chapter of Noah/Nūḥ 3,363 times, in accordance with a dream of a man who saw the Messenger of God (Muhammad), may God’s blessings and peace be upon him, who instructed him to read [the chapter] that way.” These mistakes could have occurred in the translation from Arabic to French and then to English. See the original French translation in Gaston Wiet, “La Grande peste noire en Syrie et en Egypte,” in Etudes d’orientalisme dediees a la memoire de Levi-Provencal (Paris, G.-P. Maisonneuve et Larose, 1962).

[9] Ibn Baṭṭūṭah, Riḥlat Ibn Baṭṭūṭah al-musammāh Tuḥfat al-nuẓẓār fī gharā’ib al-amṣār wa’l-‘ajā’ib al-asfār, ed. ʻAbd al-Hādī Tāzī (Rabat: Wizārat al-Thaqāfah, 2004), 1:325. For a strong translation of this episode see Ibn Baṭṭūtah, The Travels of Ibn Battutah, ed. Tim Mackintosh-Smith (London: Picador, 2002), 39.

[10] The famous Mamlūk Egyptian history al-Maqrīzī also notes this procession and gathering in his history but it does not appear that he was an eyewitness to the event. However, the fact that he notes the gathering in his history demonstrates that the news of the event had become widespread; al-Maqrīzī, Al-Sulūk li-ma‘rifat duwal al-mulūk, ed. Muḥammad ʻAbd al-Qādir ʻAṭā (Beirut: Dār al-kutub al-‘ilmiyya, 1997), 4:85.

[11] Samuel K. Cohn, “The Black Death and the Burning of Jews,” Past & Present 196, (2007): 3-36.

[12] The preeminent historian of the Black Death and the Middle East Michael W. Dols states that the, “Muslim reaction to the Black Death was characterized by organized communal supplication that included processions through the cities and mass funerals in the mosques. There is no indication of the abandonment of religious rites and services for the dead but rather an increased emphasis on personal piety and ritual purity.” The communal events played a therapeutic role in bringing the city together and being grateful for those who were still living. In contrast, Christian societies emphasized personal redemption and penance from sin; Michael W. Dols, “The Comparative Communal Responses to the Black Death in Muslim and Christian Societies,” Medieval and Renaissance Studies 5, no. 1 (1974): 279. For more on Christian responses to the plague see Rosemary Horrox, The Black Death (Manchester, New York: Manchester University Press, 1994).