The Black Muslim Atlantic Symposium was held on 30-31 January 2020 at Duke University, bringing together community members, religious leaders, academics, and students and faculty from Duke University and the University of North Carolina Chapel Hill. The initiative was spearheaded by Duke’s Muslim chaplain, Imam Abdul Hafeez Waheed, and Duke Professor and director of the Duke Islamic Studies Center and the Duke Middle East Studies Center, Dr. Ellen McLarney. The name of the conference was inspired by Margari Aziza, co-founder and program director of the Muslim Anti-Racism Collaborative, who coined the term Black Muslim Atlantic to build upon Paul Gilroy’s concept of the Black Atlantic, which maps trans-national cultural connections across the African diaspora. The goal of the symposium was to honor the Black Muslim community’s legacy, past and present, in North Carolina and beyond.

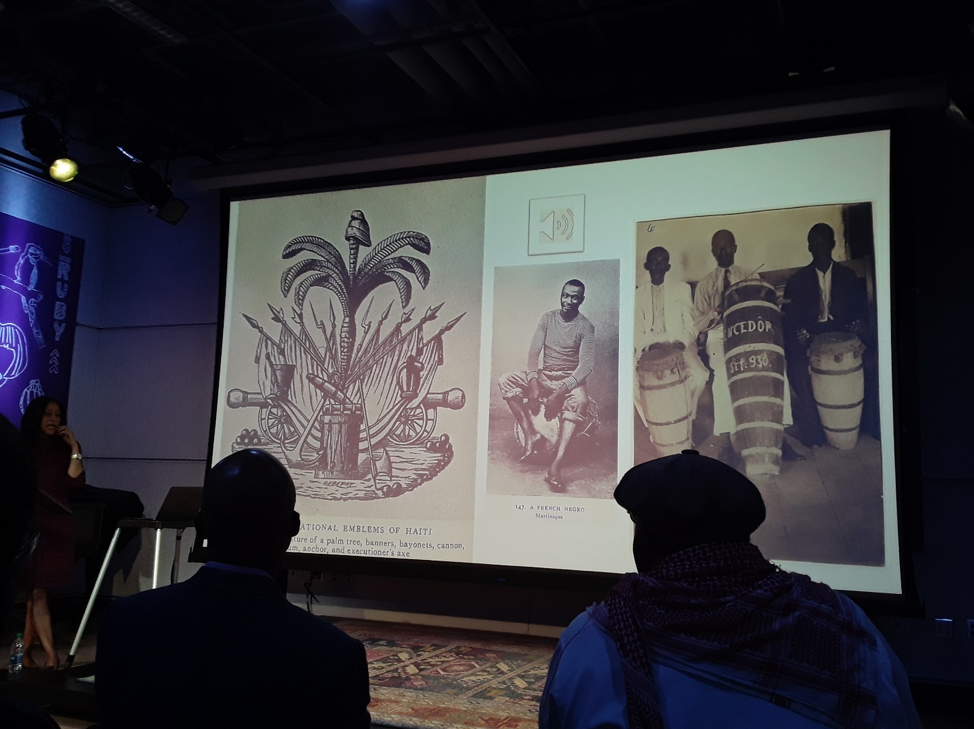

Dr. Sylviane Diouf presented the keynote for the conference, titled “Islam and the Blues.” Dr. Diouf is a Visiting Professor at Brown University’s Center for the Study of Slavery and Justice. In her address, Dr. Diouf made the case for a deep link between the blues tradition – “the mother of American music” – and West Africa and Islam. She started with examples of the chanting of the Quran and the sung prayers of Sufi orders in West Africa accompanied by images of instruments that later developed into banjo and drums in the Americas. The Transatlantic slave trade brought individuals from West and Central Africa, many of them of Muslim faith. These Africans brought with them their music, and their descendants developed this ancestral art over time. One curious observation emphasized by Dr. Diouf is that the drum is absent in much of the African American music of North America while it remains fundamental in South America and the Caribbean. The absence of the drums can be traced to the Stono Rebellion in South Carolina that took place on 9 September 1739; there, drums were used by those enslaved as a part of the march. In the aftermath of the rebellion, all forms of drums were banned due to the instrument’s link to the resistance movement. Slowly, beats on the body replaced the beats on the drum. At the same time, a singing tradition termed the “holler” was maintained and developed, with songs incorporating stories and pain from forced labor, lynching, and general terror. Dr. Diouf played Quranic recordings from West Africa and juxtaposed them with “holler” records to show the kind of similarities that could be traced in the sound and tone of both. “Holler” later developed into blues, and blues was to inspire a vast genre of American music including jazz, early country, rock, R&B, pop, soul, and funk. This vast music landscape, concluded Dr. Diouf, traces its roots to Islam.

Next, Marvin X Jackmon, who also goes by El Muhajir, a poet, playwright and essayist based in California, spoke. He is one of the pioneers of black studies in the United States, campaigning in 1967 for the first black studies department at San Francisco State University. As a poet laureate for the conference, he presented an emotional and poetic tribute to his friend, Nisa, whose death he had learnt about while on his trip in Durham. Jackmon reiterated to us how he had been “fished” into the Nation of Islam and how he became a Muslim before he became conscious of his Blackness and later became active in the Black rights movements.

The second day of the conference started with a tribute to C. Eric Lincoln offered by his widow – Lucy Lincoln. Mrs. Lincoln spoke about the intellectual trajectory of Dr. C. Eric Lincoln until he arrived at Duke University in 1976 and where he remained until 1993. She noted how their children continue the legacy of Dr. Lincoln through interfaith work in the region.

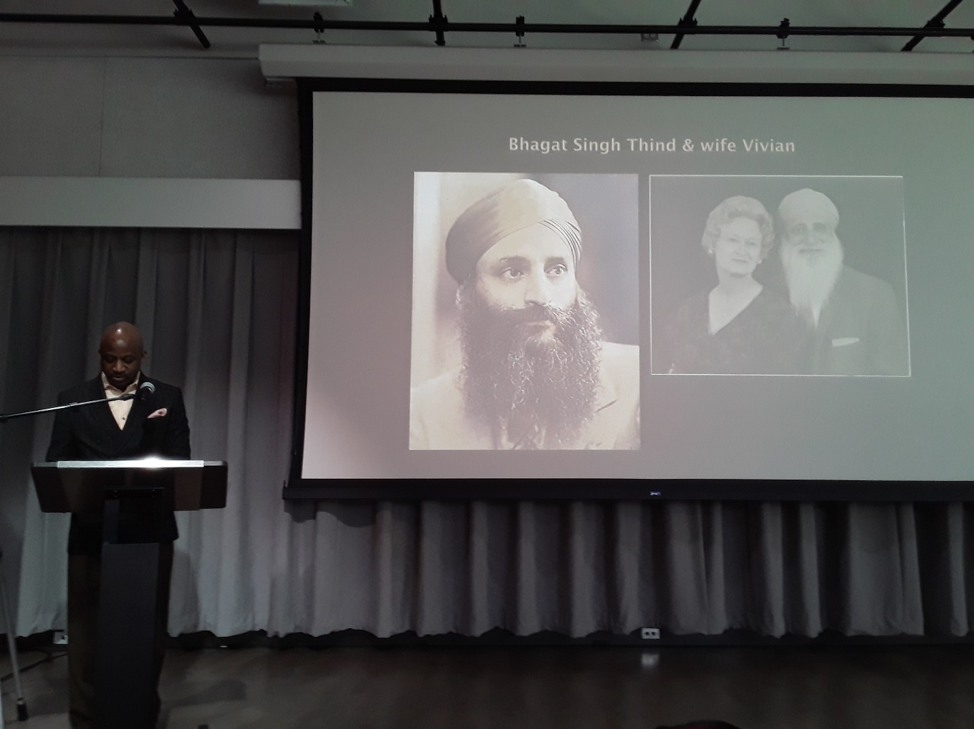

The first panel – “The Atlantic” – began with Dr. Zain Abdullah’s talk titled “Islam and Race.” Dr. Abdullah is an Associate Professor of Religion at Temple University. In his talk, he traced the genealogy of the term “Black Muslim Atlantic” in the American context. The goal of the presentation was to show “how race trumps religion and how religion qualifies what it means to be a racial person.” He started with the intricate connections between whiteness and citizenship in the United States since the 18th century, referencing cases where Arabs and Asians portrayed themselves as white (and in many cases failed to prove their whiteness) in order to gain access to American citizenship. One noteworthy example was that of Tom Ellis, a Syrian immigrant applying for citizenship who proved his whiteness through his Christian faith – this religious-based argument for citizenship was accepted, unlike in the case of Ahmed Hassan, a Yemeni Muslim. While whiteness and Christianity came to be tied in the US, Islam and Blackness came to be synonymous with each other and defined in contrast to whiteness. Dr. Abdullah then traced the genealogy of the term Black Muslim Atlantic, starting with Paul Gilroy and Cedric Robinson’s writings to Mustafa Bayoumi and Margari Aziza writing about Black Muslim Atlantic.

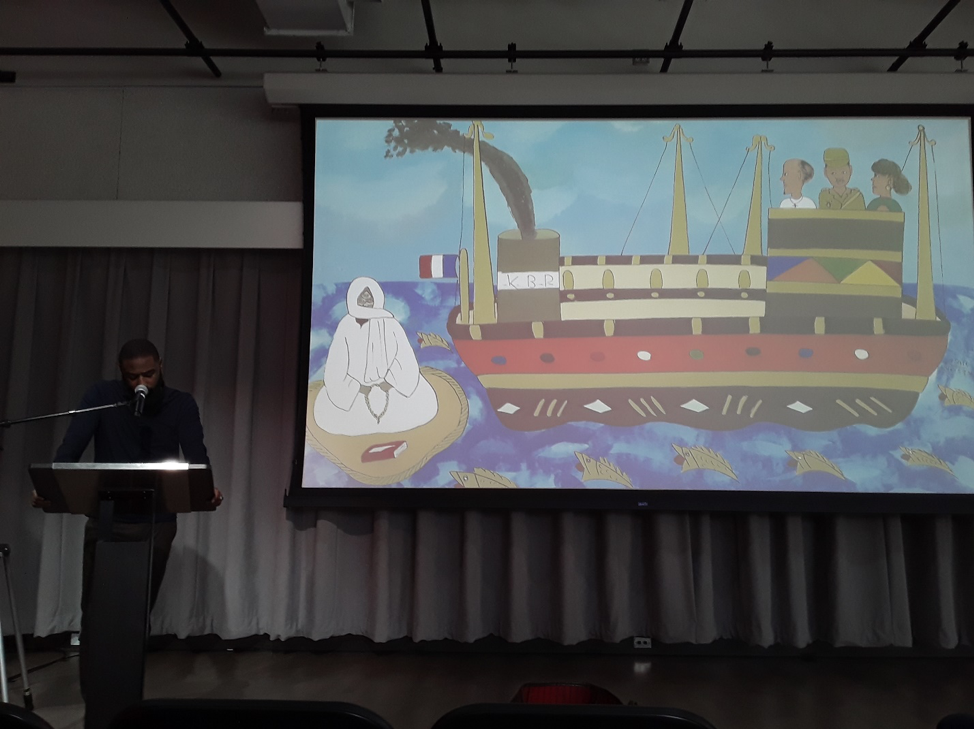

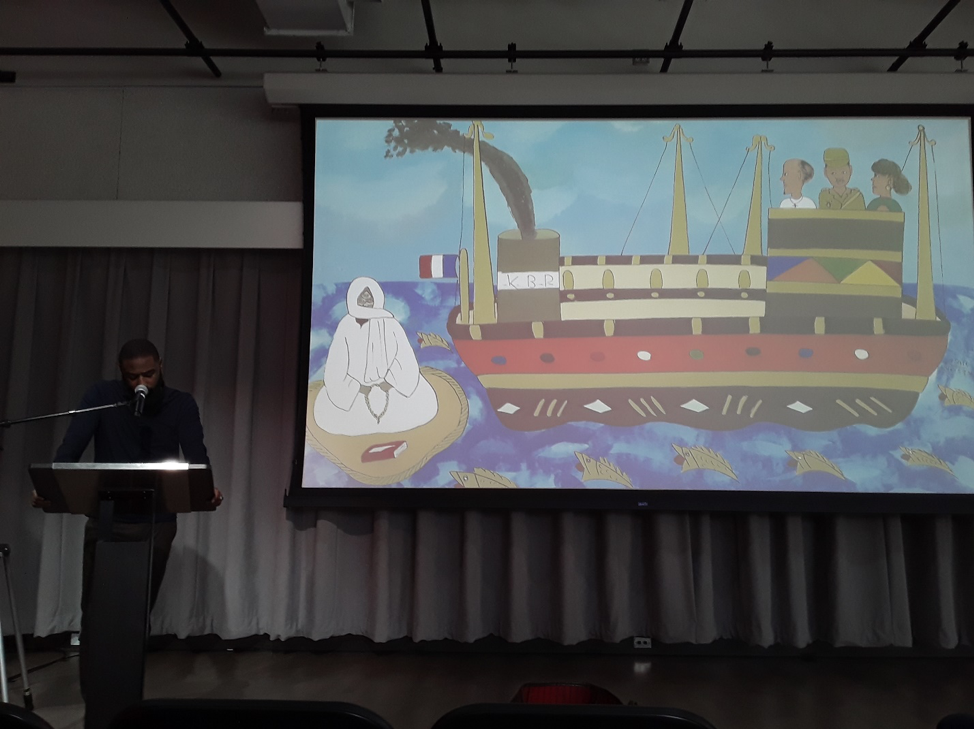

Rashida James-Saadiya and Dr. Youssef Carter presented a talk titled “A Sea Without Shore” concerning the importance of commemoration and linked rituals. James-Saadiya is an Arts and Culture editor for Sapelo Square and Dr. Carter is a College Fellow in social anthropology at Harvard University. James-Saadiya talked about spiritual pilgrimage and ancestral worship in the practices of Black Muslims. She highlighted the reconceptualization of the Atlantic Ocean as a “space of [ancestral] memory” for Black Muslims today, given that many of those enslaved in Africa died while on the ocean before they could arrive to the Americas. Death, among the West African Muslim communities, is “marked as a period of transition rather than end” and ancestors are called upon for their wisdom. Hence, “through this lens, the ocean [becomes] not only a site of grief but a liminal space that welcomes one’s spiritual, individual, and communal self.” The remembrance of these ancestors through storytelling, mixing history and fiction, itself becomes an act of Black resistance for James-Saadiya. Dr. Youssef Carter’s presentation stressed the importance of commemorative practices in West Africa and its spiritual links with the Atlantic Ocean as a way to think about “sacred kinship and decoloniality.” The remembrance of Allah as the sovereign, in the context of colonial rule, became a way of resisting the sovereignty of the French colonizers. Dr. Carter gave the example of the miracle of Cheikh Amadou Bamba, a major anti-colonial figure, narrated in the Senegambia region. Cheikh Bamba was aboard a boat, being sent into exile in Gambia by the colonial authorities when he said that it was necessary for him to perform his prayers at the obligatory time. The legend has it that, prevented from praying in a timely manner, he performed his ablutions on the boat and threw the mat into the ocean and “stood atop and prayed on the surface of water.” For Dr. Carter, the miracle is not his ability to stand on the water, rather it was his spiritual determination in the face of colonial oppression.

The second panel “Music and Sound” began with a presentation by Dr. Richard Brent Turner, Professor of African American Religious History at the University of Iowa. Dr. Turner delivered a talk on “Islam and Jazz.” Dr. Turner spoke on the subject of his upcoming book, which traces the historical connections between jazz musicians and the development of jazz as a genre, African American Islam, and black internationalism from the 1940s to the 1970s. He argued that jazz and African American Islam shared parallel goals of Black affirmation, freedom and self-determination. He focused on the revolutionary influence of Malcolm X, and the linkage between Islam and jazz as modes of resistance for African Americans. Dr. Turner mentioned saxophonist Archie Shepp, who recorded a song in Malcolm X’s honor after he was assassinated in 1965, and who noted in an interview that he saw a strong correlation between John Coltrane’s music and Malcolm’s language. Development in jazz and the spirit of Black Islam have been intricately tied, concluded Dr. Turner.

Next, Dr. Jeanette Jouili, Associate Professor of Religious Studies at the University of Pittsburgh, presented her lecture “Performing the Islamic Black Atlantic: Afro-Diasporic Muslim Hip-Hop, Embodied Ethics, and Redefinition of British Islam.” Dr. Jouli played clips from artists such as Poetic Pilgrimage and analyzed the songs’ lyrics. She explained that the work and performance of Black Muslim hip-hop artists create spaces for embodied ethics. These artists focus on Afro-Islamic claims to authenticity, which counter common beliefs that Muslims have to be of Arab or Indo-Pakistani descent to be deemed authentic. Dr. Jouli also pointed to the contested nature of this genre. Many young British Muslims, of all racial backgrounds, strongly resonate with this genre and believe that it has spiritual value, while others argue that hip-hop (and in some cases, all musical expression) is un-Islamic.

The third panel, “The Archive,” began with Dr. Jamillah Karim’s talk, “Ahmad Karim & the Black Consciousness Movement at Morehouse: Black Women Scholars Archiving their Radical Parents.” Dr. Karim is a Professor of Religious Studies emerita at Spelman College. She noted that scholars such as herself and Dr. Su’ad Abul Khabeer have started to archive their parents’ stories as a way of telling history and drawing attention to critical moments that have been overlooked or discounted in large historical narratives. Dr. Karim drew on her father’s story to counter the narrative that the Nation of Islam and Civil Rights movement were separate groups. Ahmed Karim was a prominent student leader at Morehouse College, and his conversion to the Nation of Islam was directly linked to his activism. Dr. Karim explained that Malcolm X and the Nation of Islam popularized the concept of black power and the notion of identifying proudly as black as opposed to as a person of color. Dr. Karim ended the talk explaining that you cannot tell black history without telling American Muslim history and you cannot tell that story without women.

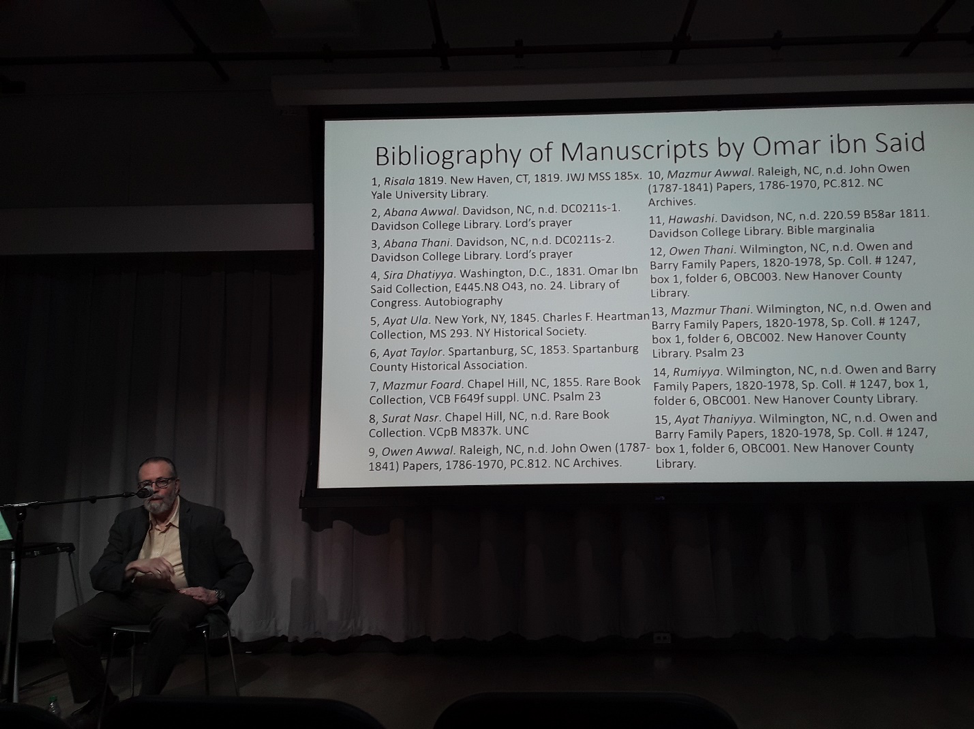

Next Dr. Carl Ernst and Dr. Mbaye Lo presented on “Omar ibn Said: Arabic and the Writings of Enslaved Muslims.” Dr. Ernst is a Professor in the Department of Religious Studies at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill and Dr. Lo is a Professor in the Department of Asian and Middle East Studies at Duke University. Omar ibn Said, whose letters and manuscripts were the focus of the presentation, is most famous for being the only known enslaved person in the United States to write an autobiography in Arabic. Dr. Ernst and Dr. Lo shared current findings from their bigger project of translating and analyzing all of Said’s surviving manuscripts. Dr. Lo began by introducing scholarship that had previously been published on Said and examining the various ways that Said as a figure has been historically constructed to suit different narratives. Dr. Ernst then walked the audience through a close reading of a letter that Said wrote to John Owen, the governor of North Carolina who was also the brother of Said’s owner. Dr. Ernst traced Said’s citations in this letter, which include verses from the Qur’an, quotes from a grammar book, and lines of poetry from a tenth century Sufi poet. Dr. Ernst emphasized that contrary to prior Orientalist scholarship on Said, he believes that the sources that Said chooses to engage with are reflective of deeper personal meanings and illustrate his engagement with a sophisticated intellectual milieu.

Lastly, Imam Ronald Shaheed, the assistant Imam at Masjid Ash Shaheed in Charlotte, NC, addressed the audience. Imam Shaheed thanked the conference organizers, participants, and attendees, and reminded everyone of the importance of emphasizing Black pride and recording and relating Black Muslim history. He credited Elijah Muhammad and the Nation of Islam for the genesis of a strong community. He ended by encouraging everyone to take what they had learned from the conference and contribute towards the future of African American Muslim communities.

Yasmine Flodin-Ali is an Islamic Studies PhD student in the Religious Studies department at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill. Her research focuses on the racialization of South Asian American Muslims and African American Muslims from the mid-nineteenth to the mid-twentieth century, and the relationship between race and religion more broadly.. You can follow her @flodin_ali.

Shreya Parikh is a PhD student in sociology at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill. She studies contemporary racialization of “Blacks” in France and Tunisia, with a focus on the study of boundaries between “Black” and “Arab” identities and its link to Islam. Her words have been published in ThePrint and The Wire. You can follow her @shreya_parikh.

*Both authors contributed equally in writing this article.