All images courtesy of Behnaz Karjoo. For more images of her work, see @behnazkarjoo on Instagram.

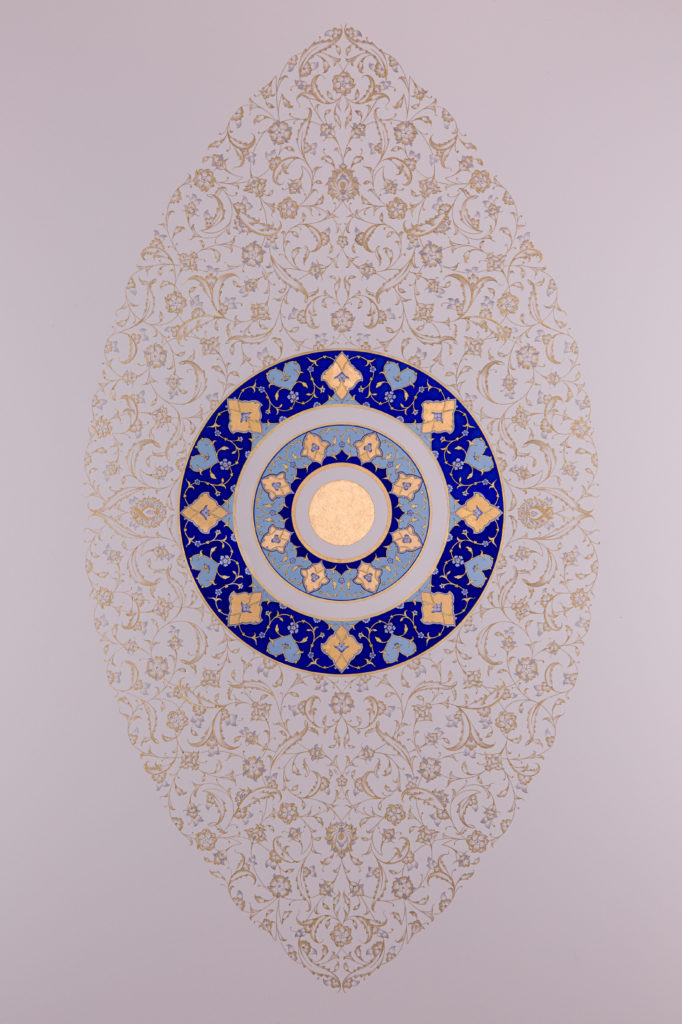

The microscopically delicate floral and yellow gold designs demanded I draw so close as to almost breathe on them. As with the other fourteen tazhib (“illumination”) works in Behnaz Karjoo’s 2020 exhibit Immanence, “The Solace of the Eyes: Qurratul-Ayn” is best viewed on different scales. Standing a prudent distance from the work means ascertaining the overall form (in this case, a Nazar-like eye), but losing the details in the almost disorienting play of light across its illuminated vine-like lines. Sufi metaphysical description of the effulgence (faiḍ) of Divine light becomes tangible in works like these. When I did defy the normal etiquette of distanced viewing, I encountered a world of complex detail hidden by the work’s minuscule scale—like focusing on part of a kaleidoscope only to realize that portion is itself another infinitely unfolding kaleidoscope.

Immanence consists of fifteen tazhib works made by Behnaz Karjoo between 2014 and 2019. The term “tazhib” derives from “dh-h-b,” itself related to the Arabic word for “gold,” and is often translated as “gilding” or “illumination.” Tazhib also describes a range of styles of techniques that have been both preserved and modified over the past seven centuries. Changes to tazhib style often directly link to changes in the socio-historical context, such as the influence of French Rococo floral motifs on Ottoman tazhib beginning in the Tulip Era (early eighteenth century). In addition to gold, both classical and contemporary works employ other materials such as turquoise, blue from lapis lazuli, green, red, palladium, and platinum (the latter two of which have replaced the quickly-oxidizing silver used in classical works).

In Immanence, Karjoo continues the tradition of “preserving while innovating” that has been central to tazhib aesthetics since the art form’s inception.

“In Immanence, Karjoo continues the tradition of ‘preserving while innovating’ that has been central to tazhib aesthetics.”

For example, in “The Solace of the Eyes: Qurratul-Ayn,” Karjoo employs a personal style within an unusual form, while simultaneously incorporating classical tazhib motifs and aesthetics. This personalized work communicates Karjoo’s religious commitments in forms that reflect her experiences, such as a meditation on the infinitude of God in the shape of the Nazar or a representation of the whirling movements of Mevlevi Sufi Dhikr. She does this in a way that implicitly challenges the dehumanizing coverage of Iranian culture ubiquitous in the wake of the United States’ assassination of Iranian general Qasem Soleimani. In the face of calls to protect pre-eighteenth century “World Heritage” sites from military strikes and relative silence regarding the impact on human life, this show resists with its contemporary preservation and innovation of Iranian and Ottoman tazhib. Just as past tazhib artists indicated their social embeddedness through aesthetic decisions, so does the unapologetic existence of Immanence respond to this moment in time.

“Just as past tazhib artists indicated their social embeddedness through aesthetic decisions, so does the unapologetic existence of Immanence respond to this moment in time.”

From Admirer to Master

Karjoo’s fascination with tazhib began well before her practice of it. She tells me that from her early childhood she had been drawn to the aesthetics, symmetry, balance, and intricacy of tazhib, be it the designs in mosques, carpets, or copies of the Qur’an. During her time at the Fashion Institute of Technology in New York, she frequently found herself incorporating aspects of tazhib into her artistic production. While she initially wanted to travel abroad to study tazhib, she actually found her master, Mujgan Baskoylu, in New York, where she was based at the time. Karjoo explained this serendipity to me with the oft-repeated saying “when the student is ready the teacher will appear.”

Karjoo began her study with Baskoylu in 2011. The first two years of her training consisted of copying designs from old manuscripts and strengthening her technique and attention to detail. Along the way she found she not only had to practice tazhib with Baskoylu, but also had to let other artistic practices go. The long strokes of figure drawing, for example, confused the shorter, finer motions required for tazhib. While her training primarily focused on the techniques and motifs of tazhib, Karjoo also dedicated herself to learning the adab (etiquette and discipline) and underlying philosophy of tazhib. She tells me that students absorb these subtle yet central aspects of training, such as enduring humility or effusive piety, from spending countless hours with their teacher.

Then, in 2013, Karjoo began designing her first original piece. She continued producing original work until she undertook her ijaza piece, effectively a qualifying capstone project that demonstrates sufficient mastery. This piece, “The Folding Essence,” employs red gold, yellow gold, gouache, and watercolor to depict the constant extending, forming, deconstruction, and refolding of the Divine essence. The culmination of this piece, and her five-year tutelage under Baskoylu, was her receipt of an ijaza (certificate of mastery) for tazhib in 2016. With this certificate, Karjoo was licensed to pass along her training in Ottoman illumination to other students, thereby transmitting tazhib to future generations.

Preserving While Innovating

Since receiving her ijaza, Karjoo has begun branching out and pushing the boundaries of her style. While Baskoylu trained her in Ottoman tazhib techniques and motifs, Karjoo has also studied with tazhib masters from Iran, and her more recent work reflects these two lineages. While the differences between Ottoman and Iranian tazhib would likely go unnoticed by an untrained eye, Karjoo remarks that Turks will tell her that her works look Iranian and Iranians will tell her the works look Turkish.

The host, Twelve Gates Arts, was attracted to Karjoo’s innovative tazhib aesthetics and her ability to explore personal themes through them. A Philadelphia-based non-profit organization and art gallery, Twelve Gates Arts hosts contemporary artists and collaborates with other arts and culture organizations around Philadelphia and along the East Coast. Although many of the artists they exhibit hail from South Asia or the Diaspora, their director and curator Atif Sheikh tells me that they shy away from self-categorizations that parochialize their content. After all, as Sheikh reminds me, it is not only White men who produce “contemporary” things. And the shows they have hosted, ranging from group meditations on Black Lives Matter to studies of diasporic material culture testify to their rejection of constraining minoritization. Although tazhib is often labeled as a “traditional art,” even described as such by Karjoo herself, Sheikh explains that the themes and meaning explored in Immanence, as well as its distinctive designs, make it more than sufficiently contemporary for their venue.

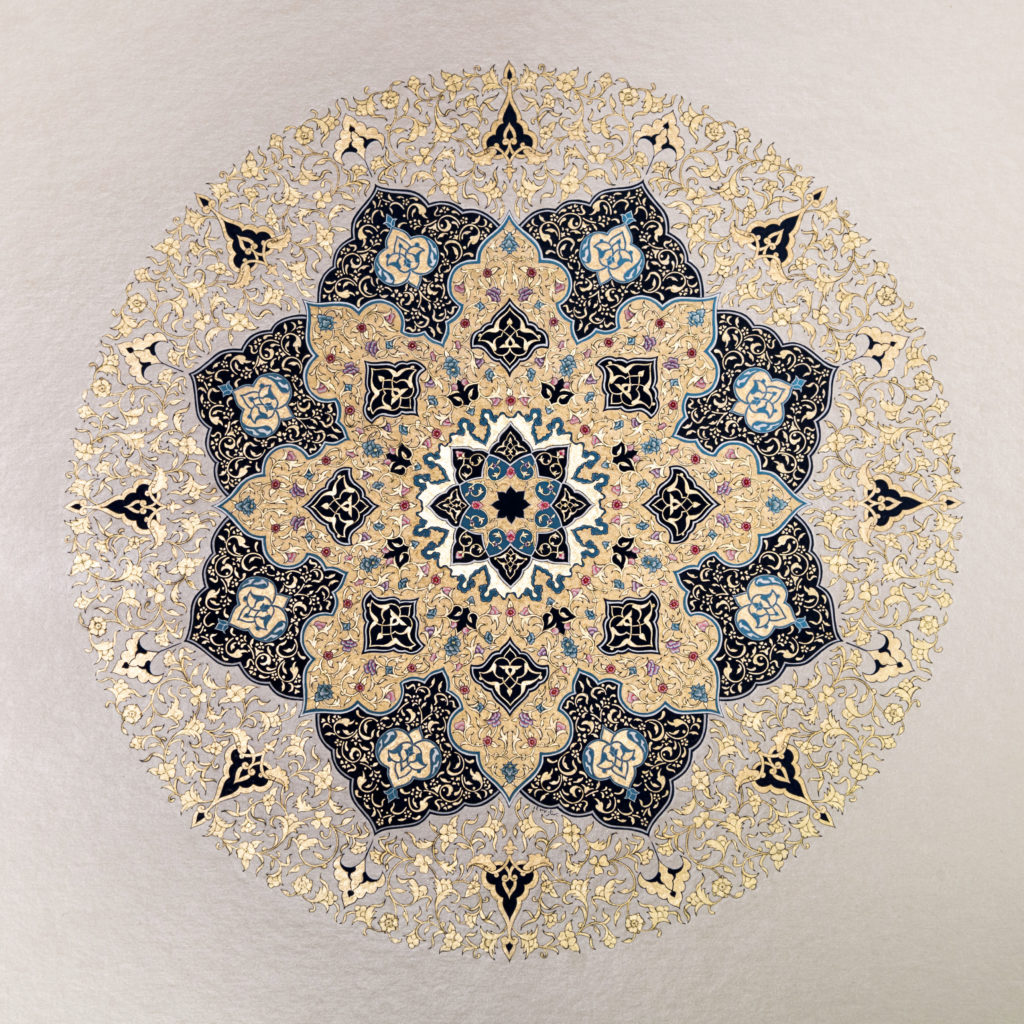

Her eclectic style and thematic and formal novelty have enabled Karjoo to simultaneously innovate and preserve tazhib. She is not unique in this regard: as she maintains, tazhib artists have transmitted techniques and motifs while also adding their own distinct impressions to the art form throughout time. In other words, the craft-art dichotomy that typifies certain Western art criticism should be ignored when analyzing novelty and tradition regarding forms like tazhib. Pieces like “Panjitan” from Immanence beautifully illustrate this preservation-innovation practice. It takes the form of the khamsa, or “Hand of Fatima” that is ubiquitous in regions in which the Evil Eye remains salient. The title “Panjitan,” meaning “five bodies,” communicates fidelity to Muhammad, Ali ibn Abi Talib and Ali’s sacred household, thereby impressing Karjoo’s religious belongings and commitments into the work. Yet, the patterns and motifs themselves, composed of deep reds of cinnabar and vivid blues of lapis lazuli form into familiar buds and flowers. And, thematically, the work pivots around a 24-karat gold center, representing the Divine source from which the five fingers/sacred figures of the hand extend.

Finding the Divine in Tazhib

Along with utilizing more synthesized motifs and aesthetics, Karjoo’s recent works also contain more handmade materials. From treating the paper to hand-grinding pigments, Karjoo personally produces most, if not all, of the elements she uses. This level of involvement in the production process means that individual tazhib pieces can take Karjoo entire years to design, prepare, and finish. Partially, this extraordinary effort stems from aesthetic preference—natural pigments yield more vibrant color and the hand-treated paper is more reliable and aesthetically rich. At the same time, these production techniques are part of a spiritual process. It connects the artist with the piece in a more layered, profound manner. And Karjoo likens the hours of pigment grinding and six months of paper-treatment setting to meditation.

“Karjoo’s divine-centric artistic process finds inspiration in this meditative material production, as well as her Islamic experience.”

Karjoo’s divine-centric artistic process finds inspiration in this meditative material production, as well as her Islamic experience. With a solid foundation in technique and knowledge of past tazhib traditions from her training with Baskoylu, Karjoo’s visual motifs are grounded in past illumination. In the process of studying masterpieces with experienced teachers, Karjoo discovered that the purpose of tazhib as a sacred art was to “reflect the divine.” With this animating goal in mind, Karjoo finds inspiration for her work from experiences that intuit her to the divine, such as dhikrs (Sufi remembrance gatherings) in New York and New Jersey, the aforementioned pigment grinding, and even dreams.

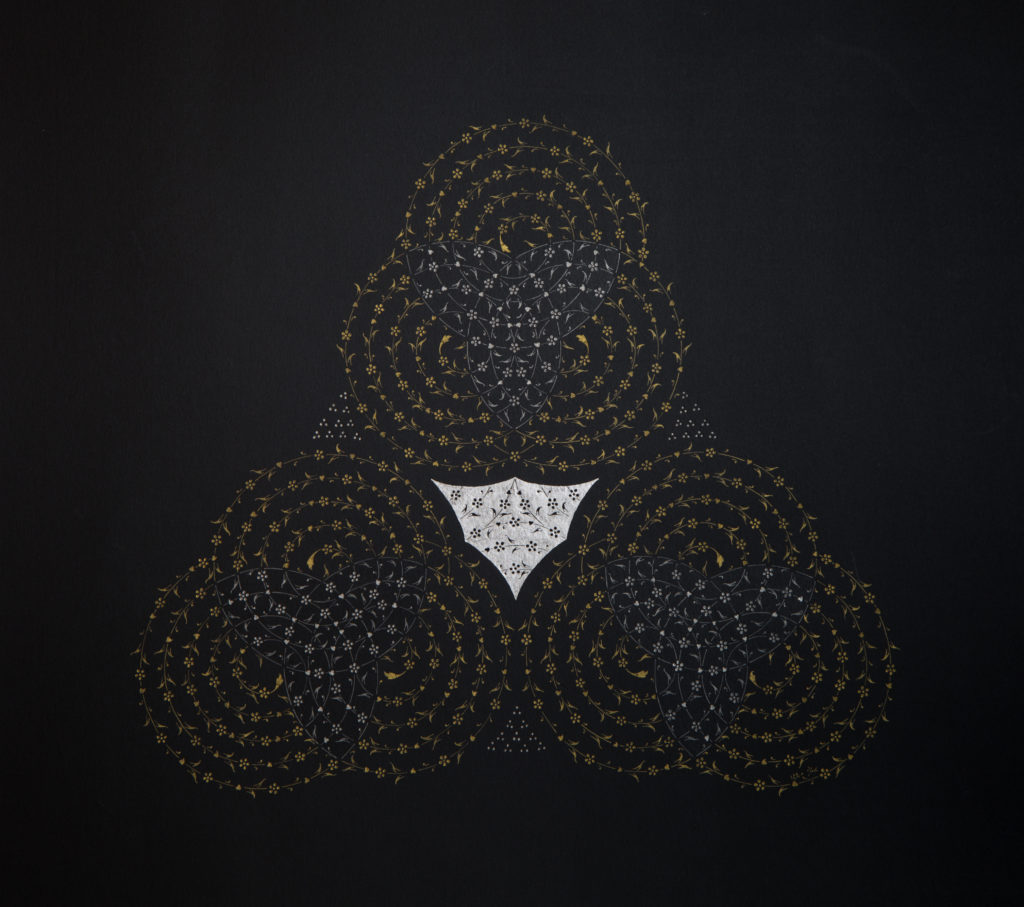

As just one example, her 2019 piece “Yearning” illustrates the influence of dhikr on her tazhib practice, with its motif of whirling rotations gesturing to Mevlevi dhikr. The swirls of 24-karat gold overlap to clarify a shimmering platinum center. Where gold against white paper can be almost blinding, the raisin black treated paper in “Yearning” flattens it. Yet, the platinum center still radiates, as if illuminating the potentially bright gold of the concentric circles enwrapping it. Karjoo writes in her description of “Yearning” that the spiraling gold represents “the circles of remembrance where Sufis inculcate and nurture this yearning, orienting themselves to the One whose light is represented in the center of the piece. The paths are many, the destination is one.”

Immanence will live at Twelve Gates Arts from January 11th until February 22nd. If you will be in the Philadelphia area, also check out Behnaz Karjoo’s Tazhib workshop at Twelve Gates Arts to be held on Saturday, February 22nd from 11 AM to 5 PM.

Immanence will live at Twelve Gates Arts from January 11th until February 22nd. If you will be in the Philadelphia area, also check out Behnaz Karjoo’s Tazhib workshop at Twelve Gates Arts to be held on Saturday, February 22nd from 11 AM to 5 PM.

“Immanence will live at Twelve Gates Arts from January 11th until February 22nd. If you will be in the Philadelphia area, also check out Behnaz Karjoo’s Tazhib workshop at Twelve Gates Arts to be held on Saturday, February 22nd from 11 AM to 5 PM.”

Max Dugan is a doctoral student in the Department of Religious Studies at the University of Pennsylvania. He studies Islamic materiality, specifically embodiment and material and visual culture, as a site for the configuration and contestation of Islamic modernities. He is currently working on projects on Islamic popular art, Halal foodways and infrastructure, Islamic tattoos, and Islam and sport.