The name Khan is trending. One Khan – Imran Khan – is now the PM of Pakistan, another, Sadiq Khan, is the Mayor of London, and in the US, Khizer Khan, a five star dad, eloquently challenged Donald Trump’s anti-Muslim rhetoric. The Khan academy is revolutionizing education in the U.S. and the Khans – Yusuf, Amir, Irfan, Salman, Shahrukh, Kareena and Saif – dominate the world’s most spectacular film industry: Bollywood. And every cricketer knows of Zaheer Khan the sultan of swing. Amir Khan the boxer and Jahangir Khan the squash champion were known for their speed and stamina. Khans like Sultan Ahmed Khan who build the magnificent Blue Mosque, were great builders. Genghis Khan, Hulagu Khan and Kublai Khan were great conquerors while Khans like Khan Abdul Gaffar Khan, tried to balance their aggression with advocacy of peace and non-violence.

“The name Khan has a glorious history and present. But glamor, politics, sports and war are not the only things that attract Khans. Known more for their brawn than their brains, the intellectual and philosophical contributions of Khans are often overlooked. It is time to make amends and to look at the intellectual contributions by those who carry this illustrious last name.”

The name Khan has a glorious history and present. But glamor, politics, sports and war are not the only things that attract Khans. Known more for their brawn than their brains, the intellectual and philosophical contributions of Khans are often overlooked. It is time to make amends and to look at the intellectual contributions by those who carry this illustrious last name. This essay identifies four Khans whose work I believe everyone should read. The selection includes a reformer, a philosopher, a poet and a religious scholar. The works of these Khans draws attention to the long tradition of reformist thinking among Indian Muslims. Through prose and poetry, these Khans have left an indelible mark on their society and tried to move it more towards science and spirituality. Plus, in these contentious times, reading these Khans will remind us of the pride these Muslims felt to be Hindustani and I believe all Indians should take pride in their work.

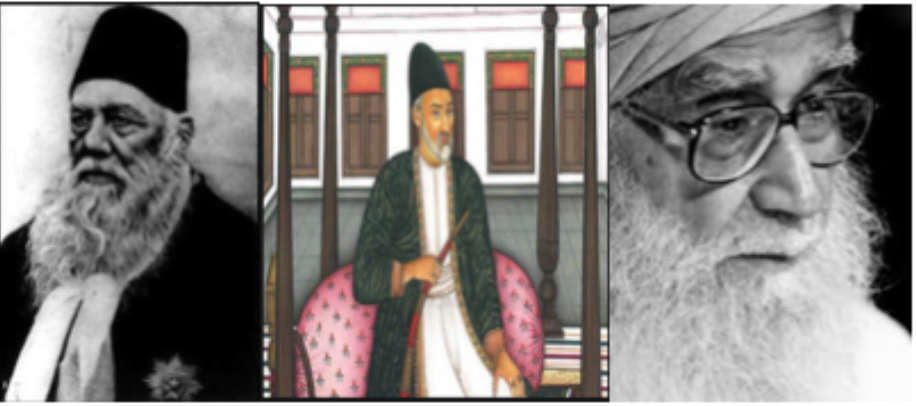

Sir Syed Ahmad Khan (1817-1898)

The first Khan of the list can be termed the dean of the intellectual faculty of khans. But more than that, he is to my mind without a doubt the first modern Muslim intellectual. He lived at a time when the advent of modernity was upending traditional societies and the growth of scientific knowledge was beginning to challenge the religious foundations of Muslim culture. His era witnessed the precipitous decline of Muslim power in India and worldwide as Western European powers began to dominate and colonize the world. He was one of the first to recognize the irreversibility of emerging global systemic shifts with the advent of modernity, and was insightful enough to call for religious, epistemological and cultural reforms.

The first Khan of the list can be termed the dean of the intellectual faculty of khans. But more than that, he is to my mind without a doubt the first modern Muslim intellectual. He lived at a time when the advent of modernity was upending traditional societies and the growth of scientific knowledge was beginning to challenge the religious foundations of Muslim culture. His era witnessed the precipitous decline of Muslim power in India and worldwide as Western European powers began to dominate and colonize the world. He was one of the first to recognize the irreversibility of emerging global systemic shifts with the advent of modernity, and was insightful enough to call for religious, epistemological and cultural reforms.

Sir Syed recognized that Indian and Muslim societies had become stagnant and weak, hence the catastrophic defeat of Mughals and other Indian pricipalities to East India Company in 1857. India was actually colonized and ruled by a British trading company and after the war of 1857 it came under direct British rule. But this defeat essentially put an end to Muslim rule in India. He argued that an intellectual reform was necessary to recognize and inculcate a scientific outlook and to make science a key component of education. For Sir Syed the pathway out of this social malaise was modern education. Hence he started what is today Aligarh Muslim University (AMU). A unique university that was not only designed to provide modern education but also to sow the seeds for social and cultural modernization. Given the current relative underdevelopment of Indian Muslims in India and Muslim nations in the World, his message to focus on education and reform is still relevant today.

In my latest book Islam and Good Governance I write about Muslim intellectual responses to modernity and their efforts to arrest the decline of Islamic civilization. You must read my book to read the fourth Khan. I found that Sir Syed Ahmad Khan had the foresight to understand the cataclysmic changes that modernity was bringing about and tried his best to initiate intellectual and institutional changes to prepare India to face the modern world.

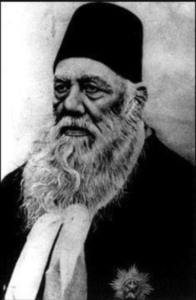

Mirza Asadullah Khan Ghalib (1797-1869)

It must count as a sin to describe a poet like Asadullah Khan in prose. Even though his letters in prose alone constitute an adab – a literary tradition, Ghalib is most famously known as the best of Urdu poets. He may not have been as formative and essential to arts and letters as Amir Khusrau, but he certainly is the most brilliant of jewels in the treasury of Indian culture. Everyone must read this Khan. Indeed a life lived without reading Ghalib is like eating a tasty dish missing an essential spice. Even as Urdu itself and the attendant adab is declining, Ghalib’s popularity does not wane, with books, musical renditions and television programs continuing to celebrate his poetry.

It must count as a sin to describe a poet like Asadullah Khan in prose. Even though his letters in prose alone constitute an adab – a literary tradition, Ghalib is most famously known as the best of Urdu poets. He may not have been as formative and essential to arts and letters as Amir Khusrau, but he certainly is the most brilliant of jewels in the treasury of Indian culture. Everyone must read this Khan. Indeed a life lived without reading Ghalib is like eating a tasty dish missing an essential spice. Even as Urdu itself and the attendant adab is declining, Ghalib’s popularity does not wane, with books, musical renditions and television programs continuing to celebrate his poetry.

In Islam and Good Governance, I wrote about the mystical Sufi concept of Ihsan and how it could bring aesthetics to politics. Ihsan is to live life as if one has had a glimpse of the divine; it is about recognizing that the purpose of creation is to do beautiful things. I believe that very few have manifested divine beauty through their lives as well as Mirza Asadullah Khan Ghalib. I chose Mevlana Rumi, Ibn Arabi and Sheikh Saadi for my arguments in the book, since their work is more recognized for their mystical nature, but make no mistake: Ghalib was a pir of pirs (mystical master) and his poetry encapsulates the mystical philosophy of all three of those masters.

Here is one of my favorite couplets of Ghalib:

Hathon ki lakiron pe mat ja ai Ghalib;

Naseeb un ke bi hote hain jin ke hath nahin hote.

Do not go by the lines of destiny Ghalib,

Even they have futures who do not have hands.

My translation does not do justice to the sheer linguistic and poetic beauty of the sher (two line poems). It is simple yet profound at the same time. Ghalib advocates for respect and recognition of the humanity of the marginalized and the hopeless. He motivates those who have been dealt a bad hand by fate and encourages them to go forth in search of their purpose. He could also be reflecting the traditional view that our destinies are not in our hands, and our fates have already been sealed. I hope this sher inspires all those who are weak and feel helpless with the promise that they too have a future.

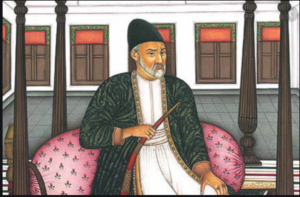

Maulana Wahiduddin Khan (b. 1925)

In spite of all the controversy surrounding his thought and politics, Maulana Wahiduddin Khan has for decades enjoyed a reputation as a very thoughtful, independent and critical Muslim thinker in India. Both mainstream and Muslim media pay extensive attention to his ideas and he has shaped the debate on key Muslim issues in India, such as the Babri Masjid conflict, the Salman Rushdi Fatwa affair, the plight of Muslim minorities in India, and Hindu-Muslim relations.

Wahiduddin Khan’s thought manifests two characteristic features – his undiluted commitment to nonviolence and his firm belief in independent Islamic thinking. Maulana Wahiduddin is a Gandhian at heart and over the decades, has been one of the most ardent Muslim advocates for peace and nonviolence. Wahiduddin Khan has made several independent Islamic contributions, including his advocacy for a renewed focus on scientific research and gender equality. He insists that science will not only authenticate the basic message of Islam but that it is imperative that Muslims rethink their understanding of Islam in the light of science.

Wahiduddin Khan’s thought manifests two characteristic features – his undiluted commitment to nonviolence and his firm belief in independent Islamic thinking. Maulana Wahiduddin is a Gandhian at heart and over the decades, has been one of the most ardent Muslim advocates for peace and nonviolence. Wahiduddin Khan has made several independent Islamic contributions, including his advocacy for a renewed focus on scientific research and gender equality. He insists that science will not only authenticate the basic message of Islam but that it is imperative that Muslims rethink their understanding of Islam in the light of science.

Thus, in his worldview, which on this subject mirrors that of Sir Syed Ahmad Khan, science becomes a pathway rather than a hindrance to faith. In a similar vein he insists that Islam always intended gender equality, and here he is much ahead of the traditional curve. He has a large global following and he has been recognized by both Indian and foreign governments for his service. Maulana Wahiduddin is easily one of the most important Muslim thinkers of our time and especially so in the context of South Asia.

I have always had a lot of respect and empathy for Maulana Wahiduddin and his mission. In 1998 I had the opportunity to debate him at a conference on Islam and Peace at the American University in Washington DC. The traditional Islamic view – and the view that is most rational in my opinion – is that there cannot be peace without justice. The Maulana was arguing that first we must make peace and then work for justice. I found that view interesting, but there is very little historical evidence to suggest that peace precedes justice, when the absence of justice is in itself absence of peace. We disagreed, but we also came out of that debate with more respect for each other.

“While these Khans have lived across three centuries there are a few common threads that run through their work. They share a deep concern for the human condition, a desire to reform and make the world a more peaceful place and finally an abiding affinity for spirituality.”

While these Khans have lived across three centuries there are a few common threads that run through their work. They share a deep concern for the human condition, a desire to reform and make the world a more peaceful place and finally an abiding affinity for spirituality. All these khans: Sir Syed, Mirza, Wahiduddin and yours truly deserve to be read at least once by everyone.

Dr. Muqtedar Khan is a professor at the University of Delaware and a Senior Fellow at the Center for Global Policy. He is the Academic Director of the State Department’s American Foreign Policy Institute (SUSI). He is the author of a new book Islam and Good Governance: A Political Philosophy of Ihsan, which was recently listed by Book Authority as one of the best all time books on political philosophy. His website is www.ijtihad.org and he tweets at @MuqtedarKhan.