There is a band from Beirut called the Wanton Bishops. They perform well, with the requisite stomping and head-bobbing you expect from “good performers.” They write coherent lyrics, mostly the blues and almost always in English. I went to a concert of theirs once, without knowing much of the band. Surrounded by twenty-something professionals who had hiked out to Jabal Amman, one of the hipster haunts of the city of Amman, Jordan, I found myself less and less interested in playing the part. I politely clapped, but checked my watch and began to plot my way home. It didn’t show, but I was also uncomfortable. Blues did not fit this context. It was a music born of enslaved peoples, a very different form of resistant joy than that found in the Arabic-speaking world. This is not debke, used at protests and weddings alike, or folk songs laced with coded resistance. The Wanton Bishops’ lyrics also felt like they were an attempt to imitate the blues, like this was something I could be hearing word for word and beat for beat in the United States. It occurred to me then that I disagreed with the Bishops’ founding principle: the blues is not a universal music, and it did not speak to my context as a twenty-something denizen of this part of the world – the Middle East and North Africa, the Eastern Mediterranean, the Arabic-speaking world, whatever we’re calling it on any given day. That, I reasoned, is why I was uncomfortable.

“It occurred to me then that I disagreed with the Bishops’ founding principle: the blues is not a universal music, and it did not speak to my context as a twenty-something denizen of this part of the world – the Middle East and North Africa, the Eastern Mediterranean, the Arabic-speaking world, whatever we’re calling it on any given day. That, I reasoned, is why I was uncomfortable.”

I would be more comfortable at a Cairokee concert, even if they’re not the most performative musicians. I’ll rephrase. They are talented live musicians, but they’re dull performers: they play their instruments without much care for pumping up the audience with theatricals. This is reflected in their music videos, which, for the last two albums at least, they produce for each song on the album: most of the time, these are stripped down, without much narrative. So Cairokee is not going to strut the stage like Hamed Sinno playing his best Freddie Mercury. They’re going to play their instruments and do it well. And they’re not always going to build inventive sets, meant to stimulate the mind and complement the music. The music sounds more or less like their records do, begging the question why anyone would want to see them live. I should just go see the Wanton Bishops instead when they’re in town, right?

Cairokee began as a musical project in the early 2000s in Cairo, Egypt. They perform exclusively in Arabic, although they originally intended to write and perform in English. However, it was their 2011 Sout al-Horeya (Freedom’s Sound) that brought them to national, regional, and greater global recognition: the video for the optimistic anthem of the Revolution showed a united Tahrir Square, with Egyptians of all stripes mouthing the lyrics to the song as the camera moved between the square itself, its side streets and onto the iconic Qasr al-Nil Bridge. The next few Cairokee LPs and EPs focused on Egypt’s chance at a future and the role of the individual within it. One could truly make a difference, Cairokee stressed, in this new world, echoed in the words of a recent book by Walaa’ Kamal documenting his travels with the band.

“Cairokee began as a musical project in the early 2000s in Cairo, Egypt. They perform exclusively in Arabic, although they originally intended to write and perform in English. However, it was their 2011 Sout al-Horeya (Freedom’s Sound) that brought them to national, regional, and greater global recognition:..”

Cairokee tried to change the world by surprising at every turn. They pulled songstress Aida Ayyoubi out of semi-retirement –she had been working mostly on Muslim devotional music– to serenade the iconic Tahrir Square in al-Midan (The Square). Al-Midan was brazen, meant to move the listener and was not meant to be a work of tremendous lyrical genius: ya-midan, kont fein min zaman? ‘Owatna fikritna wa islahna fi-wihditna. Oh, Square, where have you been? Our power is in what we think and our weapon is our unity. Other songs on the same album Matlob Za’im (We Need a Leader) speak to the future with wide-eyed optimism and a general indie rock sound. This was the music that we listened to during the Arab Spring; those of us who wanted to hear music in Arabic, those of us who wanted to hear what we were experiencing in the streets set to a danceable beat.

I still listen to some of these songs when I need a pick-me-up, but more often than not, I turn to Cairokee’ post-2014 catalogue. It is indeed a more pessimistic catalogue but there is something uplifting in hearing my own pessimism sung back to myself through a pair of headphones by a band like Cairokee. But I, like many Arabic-speakers who came of age during the Arab Spring, am also battling the tension between our pasts and our globalized presents.

“Cairokee tried to change the world by surprising at every turn. They pulled songstress Aida Ayyoubi out of semi-retirement –she had been working mostly on Muslim devotional music– to serenade the iconic Tahrir Square in al-Midan (The Square). “

So it is no surprise that part of my attraction to this period in Cairokee’s catalogue –pessimism aside– is the more consistent and unapologetic use of sha’abi music. According to Kamal, this was the innovation of the lead singer Amir ‘Eid, who once, when asked about the incorporation of sha’abi in their music in a video interview, said nonplussed “I sing sha’abi because it is fun.” Sha’abi is no doubt a fun genre of music; it and its relations, like mahraganat and electro-sha’abi are the unofficial soundtrack of Arab and more specifically, Egyptian parties. It is what is blasting out of taxi cabs and what gets the young and the old alike tapping their feet. It is the music I used to hate to love and is now the music I unabashedly love. Historically, sha’abi is a genre rooted in the countryside. Thus, its incorporation into the mainstream is a result of increased urbanization in the late twentieth century. This is why it is popular across generational divides: it is an earworm. The genre itself has been subject to a more electric sound in the twenty-first century and it has also been mimicked by Arabic-language artists from beyond Egypt, but no one has quite taken it where Cairokee has.

“Historically, sha’abi is a genre rooted in the countryside. Thus, its incorporation into the mainstream is a result of increased urbanization in the late twentieth century. This is why it is popular across generational divides: it is an earworm.”

Cairokee’s rock-and-roll take on sha’abi is one thing, but Cairokee’s pessimistic lyrics also fit sha’abi well, because it has a history of accommodating social critique. However, Cairokee is no longer doing what it did in the early days of the Arab Spring. The band is no longer offering directives on where Egypt –both on a communal and individual basis– should go. Instead, the band expresses how difficult it can be to live in Egypt today. 2014’s Walla Ma Aayez (I Truly Don’t Want) expresses the desire for a simple life; melodically, it is unsettingly still. Eid counts off things he wants, the song’s central motif, like a cup of tea or a happy family. But then comes Walla ma ‘Ayez ila… Ibtisimatat an-nas fi-shar’i. I don’t want more than …the smiles of people in the street. Eid communicates that he understands that greater societal happiness is linked to the individual, but more importantly, that his society, in Egypt and perhaps in the greater region, is not happy. Cairokee’s frustration with reality grows. In Hodna (Ceasefire), off their 2017 album No’atta Beida (A White Spot), we find the lyrics kafrt bi-kul haga ila rabi…Ghasalt Nafsi min ‘urf al-bashar…I don’t believe in anything anymore but God…I have washed myself [free] of how man behaves. There’s a confusion that comes with disillusion: where to now? What do we believe now? And who do we believe in?

The most interesting tool in Cairokee’s toolbox is their thematic consistency, both in terms of their lyrics and their musical composition. I first picked up on it when I listened to 2014’s Sekka Shamal (A Left Turn), their third album. There’s a recycled tune I could hear in Nefsy Afagar (I Could Blow Up {the Streets}), the same tune underlying 2011’s Sout al-Horeya; it was almost as if the band was wagging a finger at its past self, telling it that nothing had really improved, despite their 2011 optimism. Nefsy is essentially a tour through Cairo’s streets and Eid sings of societal problems like traffic, drug culture, and sexual harassment, all to an upbeat tune. When the song came under fire for its reference to explosions, Eid, again nonplussed, said the song was about sitting in traffic and hating it.

“The most interesting tool in Cairokee’s toolbox is their thematic consistency, both in terms of their lyrics and their musical composition.”

In comparison to the musical themes, the lyrical themes are more overt in Cairokee’s work. These are repeated phrases in lyrics. Cairokee is not afraid to be self-referential: it is a continuity, a conversation across time. Opinions develop over time. They grow and shift. Their conception of a wrong turn, sekka shemal, begins as a state of confusion in 2014’s Sekka Shemal. By 2017, Cairokee openly says that this is a different world than that of the utter confusion they found in 2014; they directly reference how they revisit the lyrics of 2014 Afdal aghani thani wa ‘aid fi kalamy (I prefer to sing again and repeat myself). Instead, they acknowledge they come back to the sekka shemal, and not just one left turn but seka shamal fi shimal, one wrong turn after another; a world where those who are low reign and the cheap is expensive. This is a normative experience, this is everyday life.

Ideas can be layered upon ideas. Something that was a passing occurrence has since become more developed. Ghurba or to be gharib, to be mitgharib, to feel alienated, is something you find even in their earliest music. Gharib fi Bilad Ghariba (Stranger in a Strange Land), itself is really one song with two iterations and was written, according to Cairokee lore, before the revolution: one is alternative-rock and one came at the dawn of Cairokee’s sha’abi era, 2013-2014. By 2017’s Hodna, to be alienated is also a normative state. Ana mitgharab..istisalam shakl al-salam. I am alienated; surrender can look like peace. Perhaps we have all surrendered.

Cairokee is not unique in recognizing the need for change across Muslim and Arab-majority countries; this is something most of us, across demographics, acknowledge in some way. But it is their bravery that I applaud. Journalists and academics might be at the front lines, but with certain exceptions, music has been largely quiet. Mashrou’ Leila is not brave the way Cairokee is. This is a band who stuck it out alone, who organizes everything themselves; they are their own managers, their own product designers. Cairokee’s lyrics target particular problems experienced across social strata. This is a band whose albums have been banned by the government of the country they reside in and when going up against the censorship board, they’ve largely been cheeky. To live in Egypt is not to live in Lebanon. Cairokee’s audience recognizes this and cites Cairokee’s shuja’a, their bravery, as one of the things that attracts them to the band. On the flipside, some critics have been brash enough to say that Cairokee’s music is out of date; that it was more in time with the Arab Spring but today means little. To say so, however, ignores Cairokee’s mission: Cairokee is not instructive or prescriptive to its audience. They are not here to preach to their audience. Instead, Cairokee is reflective of its audience: an audience that feels alienated and unsure of its place in the world, that needs change, but might not be sure of what exactly to do. They will figure out the path forward as the audience does, if there is a path forward, that is.

And Cairokee still sings love songs, because they and their audience still love and fall in love. Their first love-songs, back before the Revolution and the Arab Spring, had that air of someone spurned, someone perhaps a little young for true love, fixated on those moments that we endow with meaning in their present, but forget later. Their later ones are about the everyday of love, celebrating it, rather than underlining its heartache with a thick felt pen. ‘Ashanik ana ‘adir akamil – Because of you I can bear {the day}– Amir Eid sings in Layla, a 2017 song dedicated to his wife. Then there’s religion: Cairokee still acknowledges the role of God in public life. There’s that lyric from Hodna: I don’t believe in anything anymore but God. It is followed soon after by Lissa fi iman fi ‘albi (there is still faith in my heart). For a band in the landscape of post-revolutionary Egypt, where there are noted turns, especially by some elites, against religion; this is extraordinary. This an Egypt where women are being turned away from North Coast restaurants, hotels, and beaches because they wear hijab, where disillusion with religious authority and religion itself is beginning to feature in certain corridors of everyday life. But it is also a God defined by Cairokee’s relationship with it; and it is a persevering relationship at that. There is a kind of hope here and a lack of compliance with the status quo.

I am not Egyptian, but Cairokee is my band, not the Wanton Bishops or Mashrou Leila. There’s this flush of extreme pride in a band that seriously thinks about the meaning of culture in Arabic-speaking countries. They do not simply take musical styles born abroad, fashioned in cauldrons of another people’s pain like jazz or hip-hop or the blues, and assume that we, the Arabic-speaking public, want to consume it. They do not assume that to be cultured we need to consume the high culture of others. They acknowledge what many of us cannot: one can be pessimistic and hopeful in the same instance. That maybe if we want to see our societies change, we need to stop looking outward and look within.

But I’m not just proud of Cairokee because their lyrics and music represent me, pessimism and all. I’m proud of what they elicit in a mass audience. The last time I saw Cairokee perform, my first trip to Cairo, I marveled at the audience. I, at 26, was on the older end of the audience, but I was 18 when Cairokee made it big with Sout al-Horeya and al-Midan. The audience would have been in their pre-teens when Cairokee was at the beginning of their ascent; too young, I would have thought, to know the band’s earlier catalogue. The audience was also diverse: kids wearing designer sneakers, kids wearing niqabs, kids wearing both. They called out song titles from Cairokee’s back catalogue, these same songs of optimism and hope I remember listening to in college. It was clear the audience wanted to witness icons of a closed chapter in Egypt’s recent history. They wanted to be reminded of the promises Cairokee’s generation –my generation– had made in our art and casual conversations alike. They were engaging in the story of Egypt and the Arabic-speaking world’s last decade. Then of course, they pumped their fists along to those upbeat songs of pessimism I like to listen to when I warm up for a run or need a kick when writing in a library; the more recent catalogue that reflects where Egypt is at now. And there was something else. Earlier this summer, an Egyptian-American friend of mine went to Egypt’s first match in the Cup of Africa, which was hosted in Cairo and featured Liverpool’s Mohammad Salah. He commented how happy the crowd was, how proud. There was something of that, too, at the Cairokee concert. I watched the audience as much as I watched the band.

N.A. Mansour is a PhD candidate at Princeton University’s Department of Near Eastern Studies, where she is writing a dissertation on the transition between manuscript and print in Arabic-contexts. Her interests include Islamic studies, Arabic-language pop culture, and food.

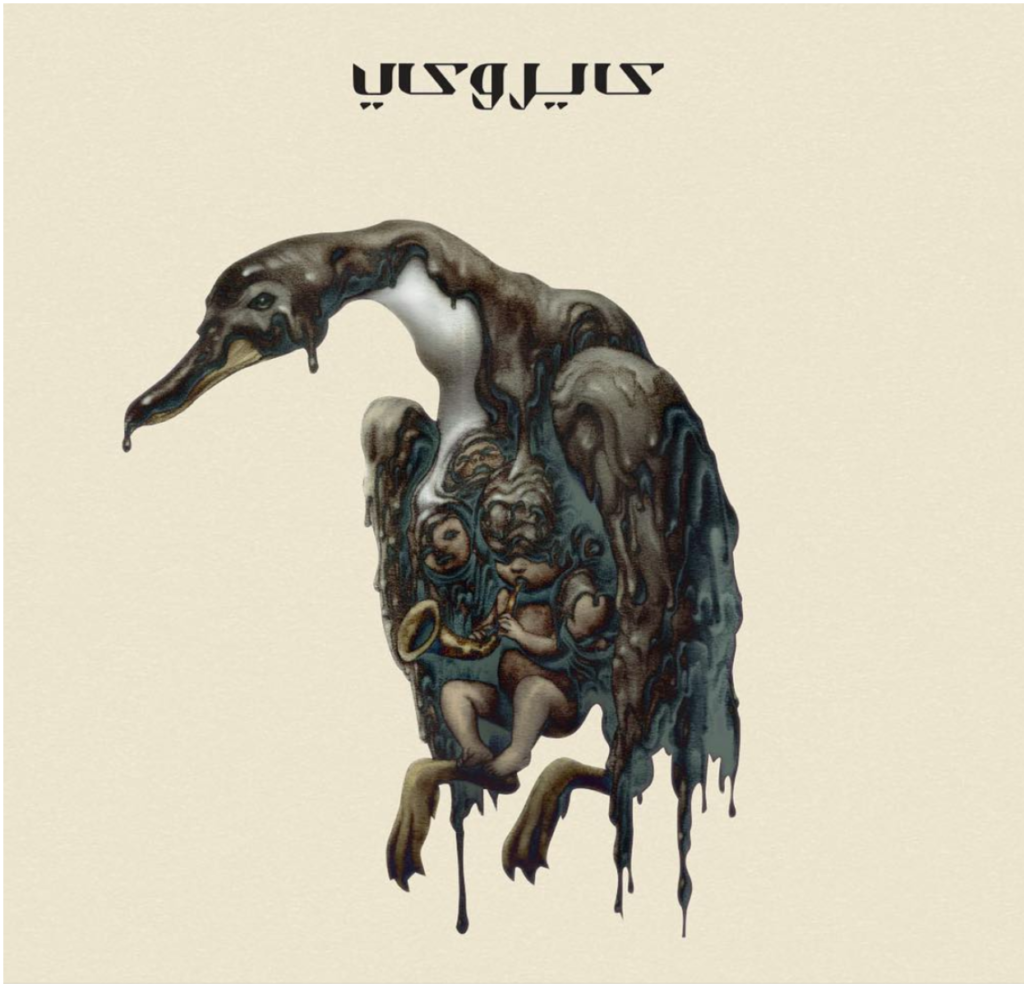

*Cover image: Cairokee performing in Alexandria, November 2019. (Source:https://www.instagram.com/p/B5qPO-_hV6D/?hl=en).