This essay is based on the author's 2019 journal article: Nermeen Mouftah, “The Sound and Meaning of God’s Word: Affirmation in an Old Cairo Qur’an Lesson.”] International Journal of Middle East Studies 51, 3 (2019): 377–394.

“If a lion could speak, we couldn’t understand him.”

Ludwig Wittgenstein, Philosophical Investigations

What is the best way to encounter God’s Word? For centuries Muslims have debated how best to approach the Qur’an’s sacred language. While classical Islamic education privileged its form through recitation and memorization, the interpretive tradition (tafsīr) elevated its content through the interpretation of its complex language. In Egypt, where Qur’an education is part of a broader turn to Islamic education (formal and informal) in contemporary revivalist trends, Qur’an study is typically divided into different classes for distinct modes of learning. Lessons for advanced students include the study of exegetical works, while those open to Muslims of all educational backgrounds focus on a teacher’s sermon (khutḅa). The most common lessons in Egyptian mosques of all sizes emphasize recitation, memorization, and proper elocution (tajwīd) for men and women with little to no background in Islamic education.

One women’s Qur’an lesson in a slum of Old Cairo, however, illustrates critical transformations in Qur’an education prompted by an anxiety over the place of understanding in Muslim encounters with God’s Word. The women’s lessons combined components of Qur’an education that, until recently, did not typically align in Qur’an education for everyday people. Through the women’s lesson we observe how increasingly, the Qur’an’s semantic meaning has come into focus in basic Qur’an education. The women’s lesson in Old Cairo is indicative of Qur’an initiatives unfolding not only in Egypt, but across the world, where scriptural interpretation takes on a new and unprecedented role among everyday Muslims.

“The most common lessons in Egyptian mosques of all sizes emphasize recitation, memorization, and proper elocution (tajwīd) for men and women with little to no background in Islamic education.One women’s Qur’an lesson in a slum of Old Cairo, however, illustrates critical transformations in Qur’an education prompted by an anxiety over the place of understanding in Muslim encounters with God’s Word.”

The Old Cairo Qur’an lesson was a project to modernize and localize Qur’an instruction—to make the Word of God available to all. The lessons that took place in the prayer room of a local community center were part of an al-Azhar initiative to spread knowledge of the Qur’an. To be sure, the women memorized and learned to properly recite the Qur’an under the guidance of their teacher and neighbor, Maryam, who was trained by a teacher from al-Azhar. Each lesson typically gathered between eight to twelve students who were neighbors and extended relatives. They learned and relearned the same short chapters, directing most of their attention to the final ten chapters. Maryam guided her students to properly pronounce and memorize a short chain of verses through the proper enunciation and elocution (tajwı̄d and tartı̄l) of the text. At the same time, they discussed the verses, centering on the meaning of unfamiliar Qur’anic Arabic vocabulary, which differs significantly from their Egyptian dialect (ʿāmmiyya).

Elsewhere I ethnographically depict the women’s Qur’an encounter through the analytic of affirmation, a performative and discursive hermeneutic practice through which the women related to the truth of revelation. Here, I focus on the emergence of semantic meaning as a focus of contemporary widespread Qur’an education. I begin by situating the women’s lesson as an effort to bring together classical Qur’an training with modern attention to semantic meaning. After elucidating the epistemic stakes of this union, I then trace the emergence of meaning-centered Qur’an practices through the material history of Qur’an lessons in Old Cairo, where I argue Qur’an recitation cassette tapes paved the way for teachers’ manuals.

By closely examining one Qur’an lesson on Chapter 107, Common Kindnesses (Al-Māʿūn), I depict how the women situated Qur’anic concepts in their daily lives. Their conversation on this chapter depicts how they related the authoritative meaning of key words (such as māʿūn [kindness], and sāhūn [heedless]), to reflect on how to live according to Qur’anic ethical terms. To affirm the Qur’an, then, is distinct from “making meaning of it,” where “making” is an individual’s creative interpretive process. And yet, as the women show us, they explore key Qur’anic concepts in their lives through discussions that form community and demand introspection—or, put another way, are deeply meaningful.

Scripturalism Among Nonliterate Women: The Epistemic Stakes of Blending Classical and Modern Qur’an Pedagogies

During eighteen months of ethnographic fieldwork (between 2011 and 2015), I studied alongside the women in their Old Cairo Qur’an lesson. I participated in neighborhood life, which was undergoing significant changes in the months and years following Egypt’s January 25th uprising. The women taught me how nonliterate encounters with the Qur’an are paradoxically deeply scripturalist. The emerging prominence of semantic meaning among lay people is a recent phenomenon that has gained little attention in the scholarship on Islamic education, despite the epistemic ruptures it exposes.

“The emerging prominence of semantic meaning among lay people is a recent phenomenon that has gained little attention in the scholarship on Islamic education, despite the epistemic ruptures it exposes.”Scholarly attention to classical Qur’an education productively illuminates alternative modes of understanding—particularly through attention to affect and embodiment—that offer crucial insights into little appreciated theories of knowledge that do not conform to critical textual practices. Classical education in the Muslim world was first and foremost a pedagogy based on discipline, memorization, and the interiorization of texts. Emphasis on this form of education risks occluding a postcolonial dissatisfaction among many Muslim reformers with classical methods that they see as rote memorization, lacking a meaningful engagement with the Qur’an.

Scripturalist trends in late twentieth century Islamic revivalism seek to mediate an immediate and accessible meaning of the Qur’an. The women’s lessons demonstrate what anthropologists Rudolph Ware and Robert Launay describe as a “hybrid epistemology” where contemporary reformers endeavor to merge classical and modern education. While they highlight the significance of merging classical and modern pedagogical practices, they observe: “It remains to be seen whether such a hybrid form of Islamic education will be capable of resolving the apparent contradictions between its very different sources.”[1] The women’s lesson, then, offers an example of this emergent form of Qur’an education.

The lessons in Old Cairo blended a classical pedagogical style that concentrates on memorization and performance with a reformist orientation towards the Qur’an’s semantic meaning—historically reserved for those already initiated in Qur’an education. By bringing together these distinct pedagogies, the al-Azhar Qur’an lesson in Old Cairo allows us to observe major epistemological shifts in new textual practices that aim to make the Qur’an more widely accessible. The lessons draw our attention to reformist trends in Qur’an education that trouble notions of understanding and meaning in relation to human interactions with divine speech.

“The lessons draw our attention to reformist trends in Qur’an education that trouble notions of understanding and meaning in relation to human interactions with divine speech.”

The Emergence of Words: From Cassette Tapes to Teaching Manuals

The material history of Qur’an education in Old Cairo offers a hint towards the emergence of semantic meaning in Qur’anic encounters for laypeople. Before al-Azhar dispatched instructors to train local teachers in the women’s community center in Old Cairo in 2009, people from the neighborhood used to gather in the prayer room of their community center to study with a different kind of teacher. For years they listened to and practiced recitation from a cassette tape, that of Shaykh Mahmud Khalil al-Husary, the first to ever record the complete Qur’an. The ubiquity of the state-sponsored 1960 recording has shaped Egyptian and global experiences of the Qur’an ever since. Husary’s voice reverberates across Muslim soundscapes. It is arguably the most influential mode of transmission of God’s Word in the twentieth and twenty-first centuries. The recitation style he employed in the recording, known as murattal, stresses the proper oral transmission of the text. Such a style of performance is pedagogical—drawing attention to individual words. Labib al-Sa’id, who spearheaded the project to produce the recording, observed a public recitation and remarked on the audience’s reception: “The audience was generally favorable and many remarked that the style of chanting used enabled them better to concentrate on the meaning of words.”[2] Husary’s recitation became a significant tool for learning to recite and memorize the Qur’an, and its wide pedagogical usage contributed to an emphasis on deciphering words in Qur’an performance. In doing so, the recording laid the groundwork for a focus on semantic meaning in contemporary educational contexts, one rooted in sound that would be echoed through texts made accessible to non-specialists.

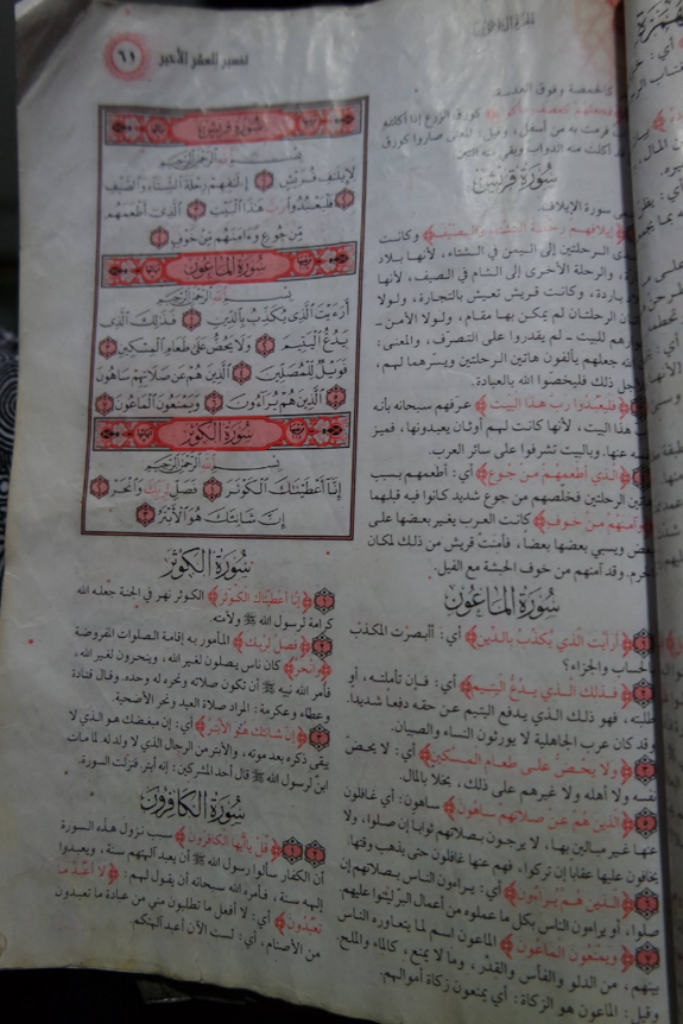

The men and women’s use of cassette tapes with clearly enunciated words created the grounds on which the simplified teaching manual was taken up. After studying the Qur’an from the cassette tape for several years, Maryam was one of only a few women in the neighborhood to train with Shaykh Umar from al-Azhar. One of the reasons she expected she was selected was because she was one of only a few women in the neighborhood who could read the teaching manual. Maryam’s well-worn teacher’s manual was The Final Ten of the Holy Qur’an: Selections from The Essence of Interpretation (Tafsīr al-‘Ashr al-akhīr min al-Qur’ān al-Karīm: Min Zubdat al-Tafsīr) by Muhammad Sulayman al-Ashqar (d. 2009). It included the short chapters of the final section of the Qur’an with an explanation of key words. The Final Ten established a fixed and authoritative sense of a word’s semantic meaning. Through Maryam’s consultation with her guide, the semantic meaning of key words established by religious authorities creates and contains access to the Word. The women’s focus on semantic meaning was enabled by new forms of tafsīr made accessible to wider audiences in abbreviated texts, and marks a new role for tafsīr in basic Qur’an education. As we will see, the women’s shift from cassette tape to teaching manual further elaborated key words through new discursive practices.

“What Is the Meaning of “Common Kindnesses”?”: Connecting Qurʾanic Concepts to Daily Life

The words of the short chapter, Common Kindnesses (al-Māʿūn Chapter 107), flowed easily from the women as Maryam reintroduced the chapter to them verse by verse. She began: bi-ism Allāh al-raḥmān al-raḥīm/ araʾayta alladhī yukadhdhibu bi-l-dīn (In the name of God, the Lord of Mercy, the Giver of Mercy. Have you considered the person who denies the Judgement?).” Some stuttered. They repeated the lines until the group was in unison. Maryam introduced more: fa-dhālika alladhī yaduʿu al-yatīm/ wa-lā yaḥuḍḍu ʿalā ṭaʿām al-miskīn (It is he who pushes aside the orphan and does not urge others to feed the needy). They echoed their teacher, and Maryam corrected their vowels. She strung together four verses to conclude the chapter. Many stumbled over the extra lines:

fawaylun li-l-muṣallīn

al-ladhīna hum ʿan ṣalātihim sāhūn

al-ladhīna hum yurā’ūn

wa yamnaʿūna al-māʿūn.

[So woe to those who pray but are heedless of their prayer (sāhūn); those who are all show and forbid common kindnesses (al māʿūn)]

Maryam explained that there is a valley in hell for those who are heedless (sāhūn) in prayer. She drew from her guide to describe two different kinds of heedless people: those who are not regular or punctual in their daily prayers; and those who pray to be seen but are not present or are insincere in their prayer. She stressed the problem of not maintaining regular prayers. Rabab, a spirited twenty-year-old whose infant daughter sat on her lap through each lesson joked about her laziness and how she never performed her daily prayers. Another woman shared that she usually prayed all her prayers at the same time in the evening, instead of at their appointed times throughout the day. Maryam related how she herself, busy with chores and children, often did this, too. Another woman, Malak, joined in: “Today, when I woke for fajr (the predawn prayer) I was happy with myself. But I knew it was Satan (shayṭān) making me pleased with myself. I know that’s wrong. Satan comes and spoils even the good things I do.”

Maryam continued: “And what are māʿūn?” When no one responded, she explained: “māʿūn are the little things we do for each other, so small we don’t notice them, but when we aren’t aware, we think they are big. We are so far away from God in our bad habits and neglect that we can’t even do the very smallest thing for our neighbor.”

“‘Maryam continued: ‘And what are māʿūn ?’ When no one responded, she explained: ‘māʿūn are the little things we do for each other, so small we don’t notice them, but when we aren’t aware, we think they are big. We are so far away from God in our bad habits and neglect that we can’t even do the very smallest thing for our neighbor.'”

The women discussed the simple gestures they could do for each other to make life easier. They complained about the lack of common kindnesses that people in the neighborhood were willing to give. Aya, who lived in a first-floor apartment beside a small shop, complained that she had no space to hang her family’s wet laundry because her upstairs neighbor refused to let her use the family’s clothesline. The others agreed that this would be something easy to allow one’s neighbor to do. More joined in. One woman was agitated because her cousin was too quick to strike her child. When Maryam sensed the conversation straying, she reined it in: “So, what is māʿūn?” She called on Umm Ahmad, who answered: “māʿūn are the nice things we forget to do for each other.” Maryam was satisfied and carried on with the lesson to individually test the women’s recitation.

The meaning of the words here was authorized by the favored interpretation of the manual and taken as axiomatic. The students drew on their experiences to elaborate the standardized explanations of sāhūn and māʿūn. Their discussions were responses to the meanings established by religious authorities that they then located in their lives. In this process, the women described the Qur’anic term māʿūn in their own vernacular, employing the word khidma (a small favor) as they considered neighborly gestures. By way of concluding the conversation, Maryam returned to the authorized meaning of māʿūn. Her question sought a vernacular explanation that spoke to the immediate economic and social stresses in the neighborhood, exacerbated by the political instability of the moment. The conversation illustrates a momentary dissolution of the sharp distinction between sacred and mundane language as a technique to render the meaning of the Qur’an relatable. The women’s discussion did more than veer away from the lesson: their conversation made a Qur’anic concept real. The meaning was not felt through an apt performance, as is well documented in the important work on the affective performance and reception of the Qur’an’s recitation. Instead, meaning was a deliberative process focused on Qur’anic vocabulary.

Islamic Reform in the 21st Century: Placing Meaning in Modern Education

The Qur’an lessons in Old Cairo intervene in debates about modernizing Qur’an education and the entailed epistemological stakes of those transformations. The women’s lesson represents not the contradiction or resolution of these blended pedagogies, but rather the emergence of a specific approach to the meaning of God’s Word, one that encourages but is not limited to a cognitive understanding of the Qurʾan’s language.

“The women’s lesson represents not the contradiction or resolution of these blended pedagogies, but rather the emergence of a specific approach to the meaning of God’s Word, one that encourages but is not limited to a cognitive understanding of the Qur’an’s language.”

For the women of Old Cairo, the truth of God’s Word must be recognized and affirmed through various modes of Qur’anic encounter: the performance of the recitation as well as the deliberative practices that center on meaning. The felicity of the women’s practice was measured in its mimetic reproduction of sound, a determined dialogic of question and answer, and the discussion of key terms authorized in the teaching manual’s gloss (sharḥ). Through their efforts, the women trouble the persistent divide between literate and nonliterate worlds. Their lesson, which blends performative and discursive Qur’anic practices, reveals to us how a scripturalist epistemology can be transmitted without the skill of autonomous reading, a skill widely regarded in Egypt and elsewhere as essential to modernity and a proper encounter with God’s Word.

From the Husary cassette tape, with its vocalization that renders each word distinguishable and audible, to the al-Azhar initiative, which employed a simplified explanation of words, we see the Qur’an made legible—even relatable—in revivalist Qur’an interventions. Maryam— literate neighbor and keeper of the teacher’s guide —directed the women in the authoritative and settled meanings of words that they echoed through their discussions. These discussions were part of a process of understanding predicated on a distinct orientation to the Word of God—so that the Qur’an is lived, adapted, rehearsed, and even sometimes forgotten. In their late afternoon circles, the women engaged in practices of memorization, discussion, and community that aimed to remember God. They connected the truth of the text to their lives, and in so doing affirmed God’s Word, and their place in the world.

*Top image: Old Cairo. Neighborhood entrance from main street.

**All images courtesy of author.

Nermeen Mouftah is assistant professor of religion at Butler University. She received her PhD from the University of Toronto, as well as graduate degrees from University College London, and the American University in Cairo. Her publications can be found in Comparative Studies in South Asia, Africa, and the Middle East, International Journal of Middle East Studies, and Contemporary Islam, among others.

[1] Ware, Rudolph and Robert Launay. 2016. “How (Not) to Read the Qur’an? Logics of Islamic Education in Senegal and Côte d’Ivoire,” in Islamic Education in Africa: Writing Boards and Blackboards, ed. Robert Launay (Bloomington, Ind.: Indiana University Press), 358.

[2] Sa’id, Labib. 1978. The Recited Koran: A History of the First Recorded Version. trans. Bernard Weiss. (Princeton, NJ: Darwin Press), 81.