As we approach the Winter holidays, it would be appropriate to discuss the common links between Christians and Muslims and especially the various figures that bring the traditions together. After 9/11, there was a strong emphasis on Abraham/Ibrahim as a uniting figure across the monotheistic traditions, most notably Judaism, Christianity and Islam. The most important academic book published during this period was F.E. Peters’ The Children of Abraham: Judaism, Christianity, and Islam.[1] As the title suggests, Peters understood the various religions as being part of one family and sought to bring together the feuding factions. As he writes in his preface, “Judaism, Christianity, and Islam are all children born of the same Father and reared in the bosom of Abraham. They grew to adulthood in the rich spiritual climate of the Middle East, and though they have lived together all their lives, now in their maturity they stand apart and regard their family resemblances and conditioned differences with astonishment, disbelief, or disdain.”[2] Peters sought to demonstrate the common roots of the various faiths and how they have more in common than modern adherents may actually think.

“As we approach the Winter holidays, it would be appropriate to discuss the common links between Christians and Muslims and especially the various figures that bring the traditions together. After 9/11, there was a strong emphasis on Abraham/Ibrahim as a uniting figure across the monotheistic traditions, most notably Judaism, Christianity and Islam. The most important academic book published during this period was F.E. Peters’ The Children of Abraham: Judaism, Christianity, and Islam.[1]“

In his forward to the book, John Esposito emphasizes the timely post-9/11 nature of the work and how interreligious understanding is now intimately connected to global politics: “Understanding and appreciating their shared beliefs and values has become especially critical for the Children of Abraham post-9/11. It is a matter no longer simply of interreligious relations and religious pluralism but of international politics.”[3] The book was recently republished in the Princeton Classics series, demonstrating the importance and significance of the work.[4]

Beyond Post-9/11 Ecumenism

But this initial post-9/11 ecumenism eventually led to skepticism as not everyone understood Abraham/Ibrahim as a uniting figure and was unconvinced of the idea of an “Abrahamic family.”

“Levenson argues that even though Abraham/Ibrahim is shared among the religious tradition, each of them have understood him differently and viewed him through their own religious lens. “In his Inheriting Abraham: the Legacy of the Patriarch in Judaism, Christianity, and Islam, Jon D. Levenson analyzed how Abraham/Ibrahim was understood within each tradition and the various post 9/11 initiatives that attempted to unite Jews, Christians and Muslims around the ancient figure. Levenson boldly concludes his book stating, “Rather than inventing a neutral Abraham to whom these three ancient communities must now hold themselves accountable, we would be better served by appreciating better both the profound commonalities and equally profound differences among them and why the commonalities and the differences alike have endured and show every sign of continuing to do so.”[5]

Levenson argues that even though Abraham/Ibrahim is shared among the religious tradition, each of them have understood him differently and viewed him through their own religious lens. Instead of creating a “new religion” around Abraham/Ibrahim, the various traditions should study both the similarities and differences between them and why the differences will continue to endure.[6]

Mary/Maryam rather than Abraham/Ibrahim?

Recently there has been a revival of Marianist studies and Mary/Maryam as a figure of commonality between Christians and Muslims. In her book Mary in the Qur’an: A Literary Reading, Hosn Abboud focuses on the Qur’anic chapter of Mary/Maryam and contends that “the story is the story of Maryam, even if it is celebrating the birth story of Jesus/‘Isa as well.”[7] Mary/Maryam “is the main character” in the Qur’anic story with the chapter named after her and with her speaking in her own voice.[8] Abboud also draws parallels between the Prophet Muhammad in Mecca and Mary as represented in the Qur’an.[9] Building off of David Marshall’s work on Christianity in the Qur’an,[10] Abboud contends that Meccan chapters emphasize Maryam more than they do Jesus and that Mary was a potential role model for Muhammad in his early preaching.

“The Qur’anic chapter Maryam discusses how Mary was approached by an angelic being, abandoned by her people and slandered, and experienced hunger, fear and insecurity but was eventually vindicated by God through the words of Jesus.”

The Qur’anic chapter Maryam discusses how Mary was approached by an angelic being, abandoned by her people and slandered, and experienced hunger, fear and insecurity but was eventually vindicated by God through the words of Jesus. Similarly, Muhammad was approached by Gabriel, rejected by his people and slandered but eventually vindicated by God through the Qur’an. For Abboud, such an association, especially of that of a man towards a woman, is not “farfetched” as there were other strong women in the Arabian context and in Muhammad’s life, such as his first wife Khadija. In her view, Muhammad identified with Mary/Maryam more than he did with Jesus, an argument supported by the fact that Jesus does not appear heavily in Meccan verses. Both Maryam and Muhammad carried the “word”; in Mary’s/Maryam’s case it was Jesus while in Muhammad’s it was the Qur’an.[11]

Nostra Aetate and Mary/Maryam

“George-Tvrtkovic ends the book with practical examples of how Mary/Maryam could play a role in intra-religious dialogue and ecumenical relations.“Most recently, Rita George-Tvrtkovic has written the important book Christian, Muslims and Mary: A History.[12] George- Tvrtkovic’s work is a concise history of how Mary/Maryam has divided Christians and Muslims but also brought them together. In contemporary times, George- Tvrtkovic notes the famous Vatican II document Nostra Aetate which evokes Mary’s name in relation to Islam. After referencing Abraham and Jesus, the document states that Muslims “also honor Mary, [Jesus’s] virgin Mother; at times they even call on her with devotion.” The statement reflects the experiences of Christian missionaries who saw how Muslims revered Mary/Maryam in their lands. George- Tvrtkovic also explores the creation of the shrine Meryem Ana Evi in Turkey which is the now visited by over a million people each year. One room is decidedly Christian with an altar and the statue of Mary while the other is adorned with the verses from the Qur’anic chapter on Maryam. Mary/Maryam further plays a role in combating Islamophobia. Muslims organizations have pointed to the fact that Mary’s/Maryam’s headscarf is similar to the Muslim hijab which could be understood to be part of the Western tradition.

George-Tvrtkovic ends the book with practical examples of how Mary/Maryam could play a role in intra-religious dialogue and ecumenical relations. For instance, Mary/Maryam can be a model today as seen in the annunciation story where she listens to Gabriel, asks questions, and accepts the goodness within his message. Contemporary Christians and Muslims invested in interfaith dialogue could “follow Mary’s lead” in listening to one another and accepting the good that the other has to offer. George-Tvrtkovic concludes that Mary/Maryam has always been a flexible tool and potential bridge between Christians and Muslims, but only when the believers choose to embrace her as such. Her concluding sentiments put the burden of ecumenical relations on the believers, not simply on God or scripture.

Conclusion

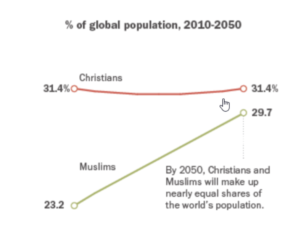

The figure of Mary/Maryam does provide its benefits in that it focuses on women issues such as that of motherhood, female emulation and religious authority.[13] Nonetheless, the emphasis on Mary/Maryam leaves out its older Jewish partner which has a stake in Abraham and the subsequent children of Israel. This focus on Mary/Maryam and Christian-Muslim relations in general is tied to the fact that the relationship between the two world religions will increasingly become significant in the decades ahead.

“This focus on Mary/Maryam and Christian-Muslim relations in general is tied to the fact that the relationship between the two world religions will increasingly become significant in the decades ahead. “According to a Pew Research Poll, in the year 2050, the global population of Christians and Muslims will roughly be the same, Muslims will make up ten percent of Europe’s population, and Muslims will be the largest religious minority in the United States.[14] With these changing demographics, it makes sense that more attention be paid to figures who are shared across religions and intellectual traditions. Maybe the figure of Mary/Maryam can be of help in fostering dialogue and harmony between the two faiths.

* Dr. Younus Y. Mirza is a Visiting Researcher at Georgetown University and Director of the Barzinji Project at Shenandoah University which seeks to enhance America’s relationship with Muslim-majority countries. To learn more about his scholarship, teaching, consulting and speaking, please visit his website http://dryounusmirza.com

[1] Peters’ 2004 book was a rewritten version of 1982 classic; F.E. Peters, Children of Abraham: Judaism, Christianity and Islam (Princeton, N.J.: Princeton University Press, 1982).

[2] F.E. Peters, Children of Abraham: Judaism, Christianity and Islam (Princeton, N.J.: Princeton University Press, 2004), XIII.

[3] Peters, XII.

[4] F.E. Peters, Children of Abraham: Judaism, Christianity and Islam (Princeton, N.J.: Princeton University Press, 2018). For a post 9/11 trade book which uses Abraham as a uniting figure see Bruce Feiler, Abraham: a Journey to the Heart of Three Faiths (New York: W. Morrow, 2002).

[5] Jon Levenson, Inheriting Abraham: the Legacy of the Patriarch in Judaism, Christianity, and Islam (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2012), 214.

[6] See also Carol Bakhos’ important The Family of Abraham: Jewish, Christian, and Muslim Interpretations (Cambridge, Massachusetts; London, England: Harvard University Press, 2014). Bakhos begins her book stating, “Over the past several years, the term ‘Abrahamic religions’ has gained purchase in scholarly and ecumenical circles to refer to Judaism, Christianity, and Islam. Its purchase in these arenas has seeped into common parlance and secured its widespread usage, especially by those who seek to foster peaceful interactions among believers in the three religions. But an emphasis on the common spiritual threads, the shared scriptural heritage and ethical teachings, can lead to major differences being swept under the rug and, ironically, breed misunderstanding. It is crucial to ask, then, exactly what is Abrahamic about Judaism, Christianity, and Islam?”

[7] Hosn Abboud, Mary in the Qurʼan: a Literary Reading (London; New York: Routledge/Taylor & Francis Group, 2014), 40.

[8] Abboud, 68. Abboud continues “Maryam is also the heroine who returns victorious from her journey after she passes through hardship, both on the personal and social level. She returns victorious, carrying her child in her arms.” For more on female voice in Islamic scripture see Georgina Jardim, Recovering the Female Voice in Islamic Scripture: Women and Silence (Farnham, Surrey: Ashgate Publishing Limited, 2014).

[9] Aisha Geissinger also draws a parallel between the Prophet Muhammad in Mecca and how Mary is depicted in the story; Aisha Geissinger, “Mary in the Qur’an: Rereading Subversive Births,” in Sacred Tropes: Tanakh, New Testament, and Qur’an as Literature (Leiden; Boston: Brill, 2009), 379-92. Similar to Abboud, she includes a feminist reading of the story in which she speaks of Mary being “subversive” and challenging the patriarchal norms of her time. Moreover, Jerusha Tanner Lamptey makes a comparison between Muhammad and Mary in her chapter “Bearers of the Words: Muhammad and Mary as Feminist Exemplars”; Jerusha Tanner Lamptey, Divine Words, Female Voices: Muslima Explorations in Comparative Feminist Theology (New York, NY: Oxford University Press, 2018), 121.

[10] David Marshall, “Christianity in the Qur’an,” in Islamic Interpretations of Christianity edited by Lloyd Ridgeon (New York: St. Martin’s Press, 2000), 3-30.

[11] Abboud, 146.

[12] Rita Georget Tvrtković, Christians, Muslims, and Mary: a History (New York: Paulist Press, 2018).

[13] Bakhos’s work does have a chapter on “The Wives of Abraham”.

[14] “The Future of World Religions: Population Growth Projections, 2010-2050,” Pew Research Center, April 2, 2015.