In the year 1256, the first Mamluk sultan Aybak endowed a Sunni law college in old Cairo named al-Mu‘izziyya, an institution built using high-quality masonry acquired from the dilapidated Rawḍa Citadel on the Nile. A few decades later, a hadith scholar and historian named Ibn al-Furāt (d. 1405) wrote a book of history while working at this law college as a professor. In the later fifteenth century, the Mu‘izziyya college fell into disrepair and was eventually demolished; no trace of it remains today except infrequent references in medieval Arabic topographies.

“That fifteenth-century Arabic texts written on low quality paper radically outlived Mamluk buildings constructed in expensive materials should not, however, surprise the modern observer. For this is an outcome of the obsessive drive to preserve key texts of knowledge in medieval Islamic intellectual circles, a phenomenon we may term the medieval Arabic archival sensibility.In Writing History in the Medieval Arab World (I.B. Tauris, 2019) I provide a window into the written culture and history of the medieval Islamic world.”

The history book that Ibn al-Furāt wrote while based there, the multi-volume account popularly known as The History of Dynasties and Monarchs, survives to this day in his own two handwritten copies, enduring six centuries of historical ups and downs – despite never having been copied again as a whole text. That fifteenth-century Arabic texts written on low quality paper radically outlived Mamluk buildings constructed in expensive materials should not, however, surprise the modern observer. For this is an outcome of the obsessive drive to preserve key texts of knowledge in medieval Islamic intellectual circles, a phenomenon we may term the medieval Arabic archival sensibility.In Writing History in the Medieval Arab World (I.B. Tauris, 2019) I provide a window into the written culture and history of the medieval Islamic world.

State Documents and Their Survival

Not every community in the pre-modern Islamic past had archival repositories that survive intact to the present. State archives in particular are often singled out for being lost to posterity. For years, modern scholars laboured under the mistaken view that medieval Islamic communities did not produce documents in large numbers (compared, for example, to pre-modern European legal or ecclesiastical collections). Yet formal chancery documents were indeed produced by governments, but were also routinely de-acquisitioned, and the paper in them put into public circulation for re-use. Arabic manuscripts of the pre-printing age, as found today in libraries around the Islamic world and elsewhere, often contain documents or narratives written on paper previously used in chanceries or other institutions. Similarly, authors would often re-purpose personal documents to write out new texts. The problem is not that documents were not produced in substantial quantities, or even that they were not preserved. Rather, what we have is an intellectual culture in which a folio or sheet of paper – as a material object – could serve a variety of social and semantic functions that could change over time.

The ‘Absent’ Fatimid Archive

One Islamic dynasty whose written records have conventionally been regarded as lost is the Isma‘ili Shi‘i Fatimid dynasty, which ruled Egypt, North Africa and beyond in the tenth-twelfth centuries, and built the city of Cairo and its institutions. For the most part, neither their formal documents nor their narrative texts (books on history, biography, administrative arts) seem to survive in ways we might expect, as individual texts or document collections. On the other hand, the religious literature of the Fatimids is better preserved for having been transported for safekeeping to the Yemen in the 1060s, where this material would be shielded from the political violence that ensued during the Fatimids’ last decades in power.

“The Fatimids left behind a rich material culture. However, the history of Fatimid texts is more chequered, and modern scholarship has for many decades lamented an ‘absent’ Fatimid textual archive.”

The Fatimids left behind a rich material culture. However, the history of Fatimid texts is more chequered, and modern scholarship has for many decades lamented an ‘absent’ Fatimid textual archive. Meanwhile, the Fatimid archive of state documents survives partially in several ways, including in formal institutions such as the St. Catherine’s Monastery in Sinai, more serendipitously within the Cairo Geniza and as copies preserved in later literary sources.

These pathways to document preservation reveal a quite different – and more varied – life cycle for state documents, as well as a radically different archival sensibility, than the kind we see in pre-modern Europe. In medieval Cairo, the textual archive is dynamic rather than static. Recent research into the Cairo Geniza shows that once the formal archive released documents for re-use in domestic, commercial, literary, religious or other contexts, the original material could remain in circulation if new material was inscribed in gaps on existing texts.

“Recent research into the Cairo Geniza shows that once the formal archive released documents for re-use in domestic, commercial, literary, religious or other contexts, the original material could remain in circulation if new material was inscribed in gaps on existing texts.”Indeed over-writing on paper is also attested elsewhere, such as in personal documents found in medieval Damascus. This kind of survival pattern is fairly common in the medieval Islamic world, and expresses one type of archival sensibility. Another kind of archival sensibility is visible in key works of Arabic historiography that incorporate older historical reports and documents including letters and state decrees, as powerfully illustrated by the document-laden chronicle of Ibn al-Furāt.

Fatimid Narrative Historiography

The Fatimids’ own production of history books was not prolific, at least not so when judged against the anachronistic expectations of modern scholarship. Yet more was written than is commonly assumed. A number of men within Fatimid Egypt, most of them servants of the state, wrote eyewitness accounts of Fatimid rule. The reports in these books are often preserved in later works of historiography. More than a dozen Fatimid-era chronicles are thus known from later history books. These include courtly chronicles by Ibn Zūlāq (d. 996) and al-Musabbiḥī (d. 1029), al-Quḍā‘ī’s (d. 1062) brief digest of world history named ‘Uyūn al-ma‘ārif and Ibn al-Ṣayrafī’s (d. 1147) unique account of the Fatimid vizierate. The copying of extracts from these books by later authors demonstrates that Arabic history-writing from Shi‘i Fatimid to Sunni Mamluk times is marked more by continuity than disruption. This continuity is sustained by historians in a way that debunks the notion of sectarian violence – deliberate neglect of texts, looting or burning of books, destroying libraries – that modern observers tend to expect would accompany the forcible wresting of political power from one dynasty by another, across a religious divide.

The seeming tragedy of the lost Fatimid archive had until recently been partly attributed to the well-known Sunni general Ṣalāḥ al-Dīn (d. 1193), who was reputed to have destroyed Fatimid libraries in their entirety. The Fatimids were bibliophiles who had collected books on a wide range of subjects well before their arrival as conquerors in Egypt. These extraordinary collections of literary gems, more than a million volumes, ordered by subject, were housed in several major libraries established in Cairo during the Fatimid era, including the well-known and publicly accessible Dār al-Ḥikma founded by Fatimid caliph al-Ḥākim in 1005. These are the library stocks that Ṣalāḥ al-Dīn allegedly destroyed on his assumption of power in Egypt in 1171. Recent studies have disproved this idea by demonstrating that the Fatimid libraries were dispersed, their contents sold over a number of years to brokers, or into private collections later found to be relatively intact, for example in Ayyubid Damascus.

Added to this, we find substantial textual evidence of the survival of many Fatimid books embedded within the composition of later chronicles. Re-use of texts of a different kind – here, historical reports valued for their capture and preservation of an otherwise inaccessible history – is another manifestation of the medieval Arabic archival sensibility.

Revisiting the ‘Archive’ as a Concept

“Fatimid history is thus preserved and commemorated largely in the inter-religious context of Mamluk historiography (Sunni authors looking back at a hugely important Shi‘i past) and these later works offer a variety of views on Fatimid legitimacy: many, like Ibn al-Furāt, presented this history without a discernible ‘sectarian’ lens.”Fatimid history is thus preserved and commemorated largely in the inter-religious context of Mamluk historiography (Sunni authors looking back at a hugely important Shi‘i past) and these later works offer a variety of views on Fatimid legitimacy: many, like Ibn al-Furāt, presented this history without a discernible ‘sectarian’ lens. This professor at the Mu‘izziyya law college in Old Cairo procured dozens of original sources for Near Eastern history of the twelfth to fourteenth centuries, many of which have not survived independently. How do we make sense of this obsession to preserve the textual assets of the past? This question directs us towards the concept of the ‘archive,’ which has been radically revisited in recent years. A relatively newfound understanding of ‘archive’ acknowledges the contingent and subjective nature of all kinds of archives, and encourages scrutiny of the power dynamics embedded within conventional documentary archives: for example, the performance of identity, lineage, community, or confessional and political hierarchies within these writings designed to be passed on to posterity as well as serving practical uses in the present. Our revised understanding of ‘archive’ also – and crucially, in the context of history-writing – entails a move away from notion of the archive as a spatially fixed entity to an emphasis on archival practices. These archival practices include collecting, sifting and incorporating source materials, with the twin aims of preserving them and making them accessible to present and future generations of readers.

This last point is especially illuminating of the working methods of a historian like Ibn al-Furāt. One key way in which we see Ibn al-Furāt apply an archival sensibility is in the fact that he does not merely accumulate but carefully orders his sources, with explicit commentary on their value in a self-reflexive language that alerts his readers to his concern for creating a reliable register of textual witnesses to history. There is further self-reflexivity in the way he identifies particular sources: he tells us that he cites well-known author Ibn al-Athīr (d. 1233) via less well-known author Baybars (d. 1325). Would the average reader need to know this? On the other hand, learned readers would value this precision.

Archival Strategies in Mamluk Historiography

Archival practices are in evidence in all manner of post-Fatimid texts that help to preserve the Fatimid archive of narrative texts. In fact, Arabic historiography is denoted in medieval Arabic scholarship by the term ta’rīkh, the noun of the verb arrakha, to mark with a date, a common feature of archival practice as well as historiography. The archival mindset driving the production of various genres of texts in the medieval Islamic world has been traced in recent years by work on archivality in early Islamic Egypt, ‘Abbasid Baghdad and pre-Ottoman urban centres in Egypt and Syria. In this way, the epistemological environment of formative and Middle Period Islamic centres of learning, including Ibn al-Furāt’s Cairo, are characterised by archival tendencies and an ‘archival fabric’ that leaves traces in both books of history and in society at large, if we consider how often books outlived buildings.

“Ibn al-Furāt curates his textual extracts in order to preserve knowledge of late Fatimid history, which extends the life cycles of his source materials and prevents their potential descent into obscurity.”

Ibn al-Furāt curates his textual extracts in order to preserve knowledge of late Fatimid history, which extends the life cycles of his source materials and prevents their potential descent into obscurity. As narrative texts of historiography are never formally de-acquisitioned – as state or other documents might be – they are liable to suffer neglect, and thence risk of oblivion. Text re-use is an omnipresent feature of medieval Islamicate archival culture in which narrative texts, like their documentary counterparts, do not simply ‘expire’ but remain living texts that enjoy afterlives where their re-use is deemed practical or desirable in fresh intellectual or social contexts.

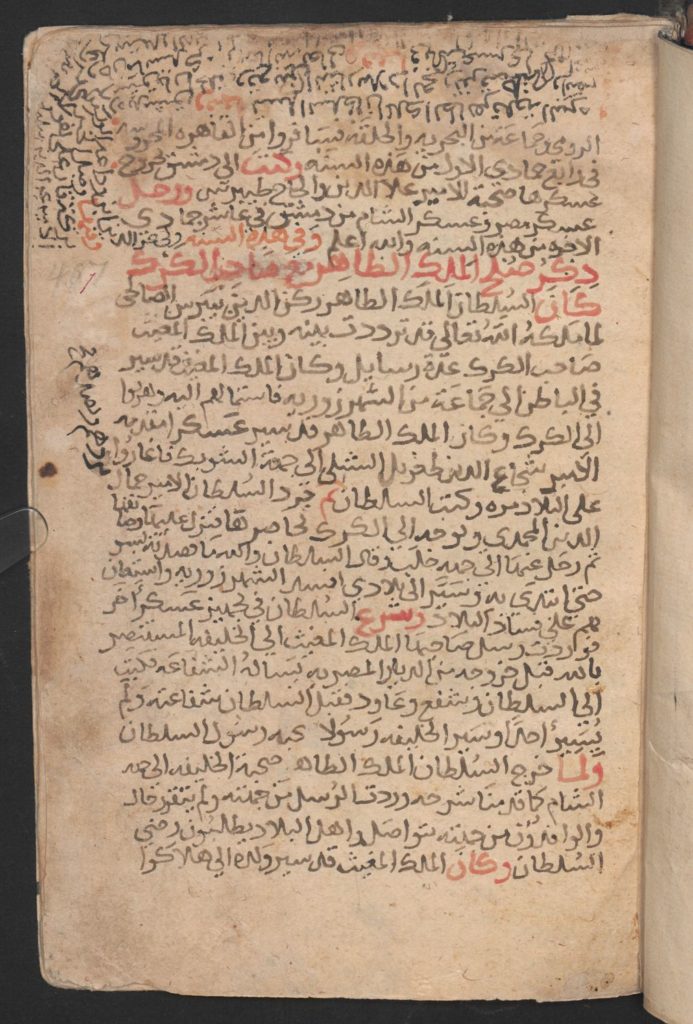

As a manuscript and as a material object, Ibn al-Furāt’s chronicle is lucid in exhibiting physical signs of archivality: the use of red ink (rubrication) to mark the start and end of citations; adding isikhrāj (or ta‘qībāt, catchwords) on pages to ensure correct order of folios; providing headings and subheadings to indicate change of topic or sub-genre; the addition of explanatory glosses within margins; and the alphabetization of obituary notices. Knowledge must be preserved, but also ordered for coherence, in this archival mindset.

The Intertextual Mamluk Archive

“The seemingly absent or erased Fatimid archive is revealed by Ibn al-Furāt’s book to have been better preserved than is often appreciated, not least through the intertextual composition of Mamluk archives of history.”The seemingly absent or erased Fatimid archive is revealed by Ibn al-Furāt’s book to have been better preserved than is often appreciated, not least through the intertextual composition of Mamluk archives of history. This ‘intertextuality’ means acquiring, extracting and citing earlier sources, and Ibn al-Furāt clearly enjoyed a special talent for finding and exploiting a wide variety of textual witnesses for each period he wrote about. Like his famous contemporary Ibn Khaldūn in the latter’s major book of history, Ibn al-Furāt brings together not just genres but widely differing religious perspectives, including Christian ones. Knowledge is valued for its own sake in the chronicle as archive, often in defiance of an author’s own religious or political pre-commitments.

The long-term dividends of looking more deeply into the archival sensibilities that shaped the writing of chronicles in the medieval Islamic world include a clearer and more specialised understanding of why history was written and by which methods. It also integrates the writing of history within a wider archival culture that allows us to clarify the intertextuality of medieval Arabic scholarly writing, as authors in various genres co-contributed to a larger archive of knowledge to be valued by present and future readers. The historian as an archivist did not typically limit himself (and it was usually a ‘he’) to memorialising historical knowledge from one type of source, but would rather cast his net widely before evaluating and then incorporating sources. Finally, the benefits of the archival method of history writing were felt not just by authors who built their reputations on this kind of effort, but also by modern scholars who may no longer be able to step into the physical institutions of knowledge production, but happily are able to handle and read the bookish monuments of that endeavor even today.

Fozia Bora is Lecturer in Middle Eastern History and Islamic History at the University of Leeds. She took her undergraduate and postgraduate degrees at the University of Oxford, and worked as a journalist before returning to academic life. Her monograph Writing History in the Medieval Islamic World – The Value of Chronicles as Archives was published by I B Tauris in June 2019. Her previous article ‘Did Ṣalāḥ al-Dīn Destroy the Fatimids’ Books? An Historiographical Enquiry’ was awarded the Royal Asiatic Society’s Staunton Prize for ‘outstanding work by an early career scholar’.

Fozia is Islam consultant for the Oxford English Dictionary (third edition), a contributor to the Encyclopaedia of Islam 3 and a Council Member of the British Association of Islamic Studies. She lives with her partner, children and cats in the beautiful Yorkshire Dales and tweets at Islamicate History (@FoziaBora).